We conclude coverage of the golden age of theatrical cartoons and their treatment of new fads and social challenges. The ‘60’s in particular brought a new round of subjects to keep characters socially relevant. First, there was the “beat” generation, or “beatnik” – a pop subculture, largely exemplified in the public eye by John Denver’s character of Maynard G. Krebbs” on “The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis”, as shiftless and lazy youth, spaced out on such things as bongo drums, non-rhyming poetry on abstract ideas, and “wailing” blues. It wasn’t a far cry from this as the Rock Generation took over – also viewed by adults as having no work ethic, but hung up on a different brand of music exemplified by the likes of Elvis Presley, the Beatles, and the Rolling Stones. Also deriving from these was the “hippie” generation, which became more accustomed to unkempt hair and beards, shabby, grungy clothes, and movements to make peace (or love), not war, sometimes referred to as “flower power”. Musical tastes would not only shift into the rock world, but affect the world of jazz, where small, “cool” combos became the popular thing as opposed to the previous big bands. The art world would also be affected, by new waves of so-called artistic endeavor resulting in a phase of “pop” or “op” art, some of which managed to creep its way into respectable museums, though few could claim to understand its reason for being.

Then, there was the dangerous rise of the “drug culture”, where youths and adults also would seek out exotic mixes such as LSD to induce “trips” of the mind into worlds of non-existence as a means of escape from reality. This led to the concept of eye-puzzling graphic design in weird colors and spirals, known as “psychedelic”. All of these strange, various, and sometimes intersecting trends managed to find their way, by one method or another, of being woven into cartoons of their time, often with intent to satirize such matters for laughs, but once in a blue moon presented with a bit of understanding of what was really going on, and maybe a tiny bit of sympathy. Many of these phases in our history seem to have long passed, though traces of a few remain. Some of the films on these varying subjects below may thus require a bit of explaining to the kids of today in order to appreciate the concepts the films were intended to convey. I hope that their presentations below will refresh a few memories, and help to place these films in proper historical perspective. However, there is entertainment value to be found, even if you personally had no involvement with nor understanding of the climate of the times.

Then, there was the dangerous rise of the “drug culture”, where youths and adults also would seek out exotic mixes such as LSD to induce “trips” of the mind into worlds of non-existence as a means of escape from reality. This led to the concept of eye-puzzling graphic design in weird colors and spirals, known as “psychedelic”. All of these strange, various, and sometimes intersecting trends managed to find their way, by one method or another, of being woven into cartoons of their time, often with intent to satirize such matters for laughs, but once in a blue moon presented with a bit of understanding of what was really going on, and maybe a tiny bit of sympathy. Many of these phases in our history seem to have long passed, though traces of a few remain. Some of the films on these varying subjects below may thus require a bit of explaining to the kids of today in order to appreciate the concepts the films were intended to convey. I hope that their presentations below will refresh a few memories, and help to place these films in proper historical perspective. However, there is entertainment value to be found, even if you personally had no involvement with nor understanding of the climate of the times.

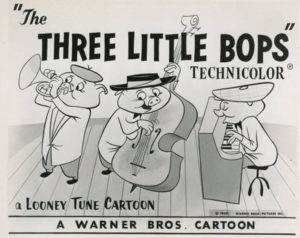

Three Little Bops (Warner, 1/5/57 – Friz Freleng, dir.) – Here’s a classic instance of someone just not making the scene. The world of progressive jazz is turned on its ear – by the ear-aching notes of the Big Bad Wolf, who has seemingly turned over a new leaf, and wants desperately to sit in and jam with the newly-formed jazz combo of the Three Little Pigs, at their current night club of residence, the House of Straw. The pigs play piano, guitar (with occasional double on sax), and a rhythm pig doubles between drums and string bass. Wolfie prefers trumpet, and so could add something to the sound – if he only knew what being “cool” meant. His best notes sound like “fluffs” half-blown past the mouthpiece, and the piano pig assesses the situation by drawing a simple geometric shape in air with his fingers – a square. The pigs pronounce judgment on the Wolf’s performance” “We’ve played in the West, we’ve played in the East. We’ve heard the most, but you’re the least!” So a bum’s rush out the door is now in order. But the Wolf still has his old temper underlying his allegedly good intentions, and finally finds the wind to blow down the club entirely, through his horn, still without hitting one good note in the process.

Three Little Bops (Warner, 1/5/57 – Friz Freleng, dir.) – Here’s a classic instance of someone just not making the scene. The world of progressive jazz is turned on its ear – by the ear-aching notes of the Big Bad Wolf, who has seemingly turned over a new leaf, and wants desperately to sit in and jam with the newly-formed jazz combo of the Three Little Pigs, at their current night club of residence, the House of Straw. The pigs play piano, guitar (with occasional double on sax), and a rhythm pig doubles between drums and string bass. Wolfie prefers trumpet, and so could add something to the sound – if he only knew what being “cool” meant. His best notes sound like “fluffs” half-blown past the mouthpiece, and the piano pig assesses the situation by drawing a simple geometric shape in air with his fingers – a square. The pigs pronounce judgment on the Wolf’s performance” “We’ve played in the West, we’ve played in the East. We’ve heard the most, but you’re the least!” So a bum’s rush out the door is now in order. But the Wolf still has his old temper underlying his allegedly good intentions, and finally finds the wind to blow down the club entirely, through his horn, still without hitting one good note in the process.

The pigs motor on to a new town, trying a new venue, the Dew Drop Inn, constructed of sticks. Wolfie follows them, and shows up again. The irritated pigs give him one more chance, but his notes are as lame as before. A unison call comes from the crowd in attendance: “Throw the square out!” Once more, the Wolf finds himself outside – and once more, a blast from his horn topples the club. The pigs vow that to keep him from playing his corny tricks, the next place they play must be made of bricks.

They find just such a location – so sturdy, its cornerstone bears a date of 1776. More importantly, the club caters only to a high-class crowd – with sign on the door, “No wolves allowed.” The Wolf’s first attempt to peer inside draws him a sock in the jaw from the fist of a bouncer out the peephole. The Wolf resorts to his trusty power-blowing, but against bricks, narrator-singer Stan Freberg recounts, “He huffed and puffed and bleeped and blooped, and at ten o’ clock was completely pooped.” So, the Wolf resorts to a series of disguises to gain entry. He first appears as a raccoon-coated collegiate, switching instruments to a ukelele. He actually strums a very listenable performance of “The Charleston” – but such a number is too out of style for this crowd. The piano pig tosses a banana peel in the wolf’s path, and the Wolf slips right out the opposite door of the club. Next, the Wolf hides inside the pot of a potted palm. A few typical clams from his trumpet, and the bass-player pig knocks him backwards out the door with a plunger, shot from his bass strings like a bow and arrow. Finally, the Wolf enters dressed as a marching band drummer, pounding a bass drum. The same pig as last time tosses a dart at the drum, deflating it like a flat tire, causing the wolf to leave in embarrassment, pounding his drumstick on the flabby, lifeless rubber of his instrument. The piano pig quickly follows, securely locking the door behind him. (Isn’t that against fire regulations for a night club? Especially after the Cocoanut Grove and Palomar fires?)

They find just such a location – so sturdy, its cornerstone bears a date of 1776. More importantly, the club caters only to a high-class crowd – with sign on the door, “No wolves allowed.” The Wolf’s first attempt to peer inside draws him a sock in the jaw from the fist of a bouncer out the peephole. The Wolf resorts to his trusty power-blowing, but against bricks, narrator-singer Stan Freberg recounts, “He huffed and puffed and bleeped and blooped, and at ten o’ clock was completely pooped.” So, the Wolf resorts to a series of disguises to gain entry. He first appears as a raccoon-coated collegiate, switching instruments to a ukelele. He actually strums a very listenable performance of “The Charleston” – but such a number is too out of style for this crowd. The piano pig tosses a banana peel in the wolf’s path, and the Wolf slips right out the opposite door of the club. Next, the Wolf hides inside the pot of a potted palm. A few typical clams from his trumpet, and the bass-player pig knocks him backwards out the door with a plunger, shot from his bass strings like a bow and arrow. Finally, the Wolf enters dressed as a marching band drummer, pounding a bass drum. The same pig as last time tosses a dart at the drum, deflating it like a flat tire, causing the wolf to leave in embarrassment, pounding his drumstick on the flabby, lifeless rubber of his instrument. The piano pig quickly follows, securely locking the door behind him. (Isn’t that against fire regulations for a night club? Especially after the Cocoanut Grove and Palomar fires?)

In a clever play on words, the Wolf returns for the final act, armed with a large drum of TNT, and proclaiming, “If I can’t blow it down, I’ll blow it up!” Freleng falls back on one of his old standby routines, with one of the pigs extending a straw out the club door’s peephole to blow out the Wolf’s ignited fuse. As Yosemite Sam might have been prone to do, the Wolf falls back several yards to out-distance the reach of the protruding straw, lights the fuse again, and charges back toward the building. Not quite fast enough. In an unusual touch, which in my childhood viewings of the film seemed so odd, I felt as if someone had entirely missed a cue for a needed sound-effect, but which to an adult eye now seems clever, the explosions of the TNT are traditionally animated, but synchronized to amplified guitar and bass notes instead of the customary Treg Brown sound effect. Thus, the Wolf disappears from the scene, without a trace except for a char mark left on the pavement. However, the camera pans below ground level, in a cutaway view to the center of the Earth, where we find the transparent red silhouette of the Wolf’s soul, boiling in a large pot over the flames of Hades. Yet, he is still playing the silhouette of his old horn – and now, the notes are coming out on key, in rhythm, and with a mellow tone. Back on the surface, his music can be heard by the pigs on stage, who pause in a moment of silence to respect the Wolf’s unexpected skill. The piano pig observes to the others, “The Big Bad Wolf, he learned the rule. You gotta get HOT to play real cool.” The pigs resume their playing, and the soul of the Wolf floats out of the ground to the stage and takes a seat with the group, finishing off the number with some hot licks. The piano pig thus changes the group’s stage sign, with a backhanded nod to Ward Kimball’s Firehouse Five Plus Two, renaming the combo, “The Three Little Bops Plus One”.

In a clever play on words, the Wolf returns for the final act, armed with a large drum of TNT, and proclaiming, “If I can’t blow it down, I’ll blow it up!” Freleng falls back on one of his old standby routines, with one of the pigs extending a straw out the club door’s peephole to blow out the Wolf’s ignited fuse. As Yosemite Sam might have been prone to do, the Wolf falls back several yards to out-distance the reach of the protruding straw, lights the fuse again, and charges back toward the building. Not quite fast enough. In an unusual touch, which in my childhood viewings of the film seemed so odd, I felt as if someone had entirely missed a cue for a needed sound-effect, but which to an adult eye now seems clever, the explosions of the TNT are traditionally animated, but synchronized to amplified guitar and bass notes instead of the customary Treg Brown sound effect. Thus, the Wolf disappears from the scene, without a trace except for a char mark left on the pavement. However, the camera pans below ground level, in a cutaway view to the center of the Earth, where we find the transparent red silhouette of the Wolf’s soul, boiling in a large pot over the flames of Hades. Yet, he is still playing the silhouette of his old horn – and now, the notes are coming out on key, in rhythm, and with a mellow tone. Back on the surface, his music can be heard by the pigs on stage, who pause in a moment of silence to respect the Wolf’s unexpected skill. The piano pig observes to the others, “The Big Bad Wolf, he learned the rule. You gotta get HOT to play real cool.” The pigs resume their playing, and the soul of the Wolf floats out of the ground to the stage and takes a seat with the group, finishing off the number with some hot licks. The piano pig thus changes the group’s stage sign, with a backhanded nod to Ward Kimball’s Firehouse Five Plus Two, renaming the combo, “The Three Little Bops Plus One”.

• A nice print of “Three Little Bops” is on Reddit.

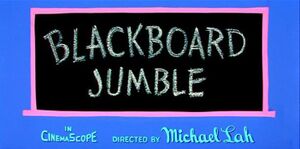

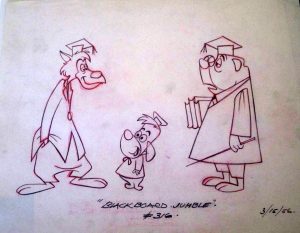

Blackboard Jumble (MGM, Droopy, 10/4/57 – Michael Lah, dir.), returns to the subject of juvenile delinquency and modern psychology methods for dealing with it. However, it pits one of the most unlikely characters from the MGM ranks against the out-of-control kids – a character whose manner and thinking patterns are so backwards and out-of-date, we can easily predict from the start who will be the victor in a battle of half-wits. Tex Avery’s Southern Wolf, in a comeback from the classic “Three Little Pups”. Voiced by Daws Butler, in his slow Southern drawl that would become the pattern for Huckleberry Hound, the ex-Civil War rebel encounters a grammar-school professor having a major nervous breakdown, making an escape from the school and experiencing fits as he bounces along the road. The wolf asks the professor what’s the matter. “Modern education’s what’s the matter. Those kids are driving me crazy. Anybody that wants this teaching job would have to be an idiot.” The professor pauses, getting a good look at who he is talking to, and dawn breaks that this scraggly wolf perfectly meets the job requirement he has just described. The professor abruptly thrusts his textbooks and pointer into the wolf’s hands, slaps his mortarboard upon the wolf’s head, and disappears screaming over the hill. The wolf observes that “Nobody has no patience no more”, and tells us that “There ain’t nothin’ wrong with modern education”, nor with the kids. However, a camera view through the window of the schoolhouse shows us a trio of identical Droopy dogs, based on the model sheet of “Three Little Pups”, having a battle royal inside the classroom. The wolf enters the room in his usual slow-mannered walk, enduring a well-timed onslaught of flying books, rubber darts, paper airplanes, lunches, and various bric-a-brac before reaching the teacher’s desk. “Cease fire, men”, the wolf calmly states. The dogs pause, not knowing what to make of the stranger. But when the wolf announces he will be their new teacher, the dogs smile among themselves, realizing he’s fair game.

Blackboard Jumble (MGM, Droopy, 10/4/57 – Michael Lah, dir.), returns to the subject of juvenile delinquency and modern psychology methods for dealing with it. However, it pits one of the most unlikely characters from the MGM ranks against the out-of-control kids – a character whose manner and thinking patterns are so backwards and out-of-date, we can easily predict from the start who will be the victor in a battle of half-wits. Tex Avery’s Southern Wolf, in a comeback from the classic “Three Little Pups”. Voiced by Daws Butler, in his slow Southern drawl that would become the pattern for Huckleberry Hound, the ex-Civil War rebel encounters a grammar-school professor having a major nervous breakdown, making an escape from the school and experiencing fits as he bounces along the road. The wolf asks the professor what’s the matter. “Modern education’s what’s the matter. Those kids are driving me crazy. Anybody that wants this teaching job would have to be an idiot.” The professor pauses, getting a good look at who he is talking to, and dawn breaks that this scraggly wolf perfectly meets the job requirement he has just described. The professor abruptly thrusts his textbooks and pointer into the wolf’s hands, slaps his mortarboard upon the wolf’s head, and disappears screaming over the hill. The wolf observes that “Nobody has no patience no more”, and tells us that “There ain’t nothin’ wrong with modern education”, nor with the kids. However, a camera view through the window of the schoolhouse shows us a trio of identical Droopy dogs, based on the model sheet of “Three Little Pups”, having a battle royal inside the classroom. The wolf enters the room in his usual slow-mannered walk, enduring a well-timed onslaught of flying books, rubber darts, paper airplanes, lunches, and various bric-a-brac before reaching the teacher’s desk. “Cease fire, men”, the wolf calmly states. The dogs pause, not knowing what to make of the stranger. But when the wolf announces he will be their new teacher, the dogs smile among themselves, realizing he’s fair game.

“First thing we’re gonna learn around here is some manners”, declares the wolf. The kids respond by offering him a chair to sit on. The wolf is touched by this act of kindness, until he spots a rope tied to the chair, by which the dogs intend to pull the seat out from under him. “Outthink ‘em”, Save ‘em from themselves”, says the wolf, grabbing the chair with both hands, and slowly lowering himself to settle down. Who’s outthinking who, as the dogs change tactics altogether, and place a firecracker upon the seat before the wolf can sit down. The blast repositions the wolf’s hips well above his elbows. Next, the wolf examines the recommended curriculum. He tosses away textbooks on reading, writing, and “‘rithmetic”, then finds one to his liking. “Finger paintin’, man!” The happy pups wheel out a blank canvas, and the wolf hands them cans of red and blue paint. “Now paint me somethin’ patriotic, like, uh…the Confederate flag!” The pups produce a perfect replica, minus one detail. “Uh oh. You forgot the stars”, observes the wolf. The pups provide an easy solution, hitting the wolf over the head with a club, which produces just enough stars from his head to complete the image. “There’s a cotton pickin’ Yankee in this crowd”, the wolf declares. The kids move on to a “Natural Aptitude Table”, basically one of those “place the square peg in the square hole” affairs. The wolf approves. “Let ‘em do what comes natural.” Suddenly, he feels a tug on his leg, as one pup drives his foot into a pre-shaped hole with a hammer. The other pups join in, and the wolf slowly disappears from view, until the camera shifts to show him tied in knots through the holes of the table. “You can’t get more natural than that, man”, he comments dryly.

“First thing we’re gonna learn around here is some manners”, declares the wolf. The kids respond by offering him a chair to sit on. The wolf is touched by this act of kindness, until he spots a rope tied to the chair, by which the dogs intend to pull the seat out from under him. “Outthink ‘em”, Save ‘em from themselves”, says the wolf, grabbing the chair with both hands, and slowly lowering himself to settle down. Who’s outthinking who, as the dogs change tactics altogether, and place a firecracker upon the seat before the wolf can sit down. The blast repositions the wolf’s hips well above his elbows. Next, the wolf examines the recommended curriculum. He tosses away textbooks on reading, writing, and “‘rithmetic”, then finds one to his liking. “Finger paintin’, man!” The happy pups wheel out a blank canvas, and the wolf hands them cans of red and blue paint. “Now paint me somethin’ patriotic, like, uh…the Confederate flag!” The pups produce a perfect replica, minus one detail. “Uh oh. You forgot the stars”, observes the wolf. The pups provide an easy solution, hitting the wolf over the head with a club, which produces just enough stars from his head to complete the image. “There’s a cotton pickin’ Yankee in this crowd”, the wolf declares. The kids move on to a “Natural Aptitude Table”, basically one of those “place the square peg in the square hole” affairs. The wolf approves. “Let ‘em do what comes natural.” Suddenly, he feels a tug on his leg, as one pup drives his foot into a pre-shaped hole with a hammer. The other pups join in, and the wolf slowly disappears from view, until the camera shifts to show him tied in knots through the holes of the table. “You can’t get more natural than that, man”, he comments dryly.

Somehow freed from the table, the wolf returns to his desk, only to find his seat replaced by a bear trap. He calmly walks over to a wall rack of convenient paddle boards. “If modern education don’t work, you gotta apply a little ol’ fashioned education.” He picks up one of the pups and prepares to perform a paddling. But another pup beats him to the punch, lighting a match between the wolf’s toes for a quick hotfoot. As the wolf leaps about in pain, the two free pups roll in on a toy fire engine. Instead of extinguishing the blaze, they raise an extension ladder to the wolf’s arm, and rescue their captive comrade, leaving the wolf on fire. The three pups retreat to a utility closet, and lock themselves in. The remainder of the film closely parallels the setup from “Three Little Pups”, with the wolf attempting to get the pups out or himself in. One new gag has him roll in a huge cannon from a human cannonball act, and prepare to launch himself into the closet. One pup opens the door and reaches out to re-aim the cannon straight up, blasting the wolf through the ceiling, and headfirst into the school bell in the building’s tower. After repeated failures, the blasted, blackened wolf addresses the audience. “Y’know, bein’ a schoolteacher takes patience. Lots and lots of patience. And lemme tell ya’ somethin’ right now…” The scene cuts to the same exterior shot where we met the previous professor, now with the wolf exiting the schoolhouse screaming and in fits, pausing only long enough to complete his sentence: “…Man, I ain’t got any more!”

Somehow freed from the table, the wolf returns to his desk, only to find his seat replaced by a bear trap. He calmly walks over to a wall rack of convenient paddle boards. “If modern education don’t work, you gotta apply a little ol’ fashioned education.” He picks up one of the pups and prepares to perform a paddling. But another pup beats him to the punch, lighting a match between the wolf’s toes for a quick hotfoot. As the wolf leaps about in pain, the two free pups roll in on a toy fire engine. Instead of extinguishing the blaze, they raise an extension ladder to the wolf’s arm, and rescue their captive comrade, leaving the wolf on fire. The three pups retreat to a utility closet, and lock themselves in. The remainder of the film closely parallels the setup from “Three Little Pups”, with the wolf attempting to get the pups out or himself in. One new gag has him roll in a huge cannon from a human cannonball act, and prepare to launch himself into the closet. One pup opens the door and reaches out to re-aim the cannon straight up, blasting the wolf through the ceiling, and headfirst into the school bell in the building’s tower. After repeated failures, the blasted, blackened wolf addresses the audience. “Y’know, bein’ a schoolteacher takes patience. Lots and lots of patience. And lemme tell ya’ somethin’ right now…” The scene cuts to the same exterior shot where we met the previous professor, now with the wolf exiting the schoolhouse screaming and in fits, pausing only long enough to complete his sentence: “…Man, I ain’t got any more!”

Alex Lovy invented for Walter Lantz the character of “Doc”, a classy but conniving cat voiced by Paul Frees, for what seemed something of a parallel to Hanna-Barbera’s Pixie and Dixie and Mr. Jinks series, here called “Hickory, Dickory, and Doc”. It was quickly found that mice Hickory and Dickory had no personality, and that Lovy wasn’t really the right fit for the series. So the mice were dropped, and newly acquired Jack Hannah, fresh from years at Disney, was given free rein to revamp the series. It was a move for the better, with Hannah beginning by pairing Doc with a bumbling beefcake as his flunky and right-hand man – a sweatered bulldog somewhat resembling Friz Freleng’s “Alf” character from the Sylvester series, but gentler, more good-natured, and definitely more gullible, with a past in pugilism that has made him punchy – hence, the name “Champ”. Champ would prove to be the fish-out-of-water and the diamond in the rough needing polishing on at least three occasions, with Doc along to proceed with the polish and gain a quick buck or a free meal in the process. The series never reached the ranks of cartoon celebrity, and lasted only a few seasons – but under Hannah’s able directing, they are overall a decent and often fun watch.

Alex Lovy invented for Walter Lantz the character of “Doc”, a classy but conniving cat voiced by Paul Frees, for what seemed something of a parallel to Hanna-Barbera’s Pixie and Dixie and Mr. Jinks series, here called “Hickory, Dickory, and Doc”. It was quickly found that mice Hickory and Dickory had no personality, and that Lovy wasn’t really the right fit for the series. So the mice were dropped, and newly acquired Jack Hannah, fresh from years at Disney, was given free rein to revamp the series. It was a move for the better, with Hannah beginning by pairing Doc with a bumbling beefcake as his flunky and right-hand man – a sweatered bulldog somewhat resembling Friz Freleng’s “Alf” character from the Sylvester series, but gentler, more good-natured, and definitely more gullible, with a past in pugilism that has made him punchy – hence, the name “Champ”. Champ would prove to be the fish-out-of-water and the diamond in the rough needing polishing on at least three occasions, with Doc along to proceed with the polish and gain a quick buck or a free meal in the process. The series never reached the ranks of cartoon celebrity, and lasted only a few seasons – but under Hannah’s able directing, they are overall a decent and often fun watch.

First came Freeloading Feline (Lantz/Universal, 9/7/60), Hannah’s debut film for Lantz. In a swank penthouse towering high above the city, a glamorous dinner party is underway. Below, in the shadows of Dishpan Alley, is the tumble-down residence of Doc and Champ. Doc has Champ in training, sounding a bell to get him started. Champ punches nimbly at a punching bag, then delivers a finishing sock to the sack, stretching its tether to the limit. It looks as though the bag will rebound back for a direct blow on Champ’s kisser – but instead, the bag settles to a rest just shy of him, and gently, barely touches his jaw. Champ’s jaw instantly develops crack lines like shattered glass – the old “glass jaw” gag Hannah had remembered from previous use in the Donald Duck short, “Canvas Back Duck”. Suddenly Doc hears wafts of dinner music coming down to his ears from the party above. He begins imagining himself attending, and starts naming a menu of the excellent fineries he would expect to find at the table there, topped off with a pantomime of opening a champagne bottle. It is apparent that he is contemplating crashing the party – but as quickly realizes that Champ is not suitably dressed for such an occasion, in his boxing turtle-neck sweater. Surprisingly, Champ disappears offscreen, and reappears in a new wardrobe, actually possessing from somewhere one formal dinner jacket to his name. Now Doc feels capable of bringing his companion along for a night of frivolity.

First came Freeloading Feline (Lantz/Universal, 9/7/60), Hannah’s debut film for Lantz. In a swank penthouse towering high above the city, a glamorous dinner party is underway. Below, in the shadows of Dishpan Alley, is the tumble-down residence of Doc and Champ. Doc has Champ in training, sounding a bell to get him started. Champ punches nimbly at a punching bag, then delivers a finishing sock to the sack, stretching its tether to the limit. It looks as though the bag will rebound back for a direct blow on Champ’s kisser – but instead, the bag settles to a rest just shy of him, and gently, barely touches his jaw. Champ’s jaw instantly develops crack lines like shattered glass – the old “glass jaw” gag Hannah had remembered from previous use in the Donald Duck short, “Canvas Back Duck”. Suddenly Doc hears wafts of dinner music coming down to his ears from the party above. He begins imagining himself attending, and starts naming a menu of the excellent fineries he would expect to find at the table there, topped off with a pantomime of opening a champagne bottle. It is apparent that he is contemplating crashing the party – but as quickly realizes that Champ is not suitably dressed for such an occasion, in his boxing turtle-neck sweater. Surprisingly, Champ disappears offscreen, and reappears in a new wardrobe, actually possessing from somewhere one formal dinner jacket to his name. Now Doc feels capable of bringing his companion along for a night of frivolity.

Before approaching the door above, our heroes are passed by another cat – flying backwards from the door. The cat has been ejected from the affair, as a trespassing freeloader. “Riff raff”, says Doc, dismissing the character as below their own class. Champ is the first to knock on the door. A voice inside welcomes him, but mistakenly addresses him as “the new doorman from the agency”. Champ is ushered in, but as an employee, and instructed to keep out all freeloaders. Forgetting everything about his friendship with Doc, Champ is swept up in living up to his new doorman role – so that, when Doc also knocks, presuming “We’re in”, he receives a chomp on the arm from the jaws of Champ. Champ spits Doc out on the patio, and when Doc asks why the heave-ho, is addressed by Champ as a “freeloader”, with the door then slammed in Doc’s face. Doc tries again, reminding Champ that they’re old friends. Champ responds by stuffing Doc down a drainpipe, then blowing through the pipe to launch Doc to the street below.

Before approaching the door above, our heroes are passed by another cat – flying backwards from the door. The cat has been ejected from the affair, as a trespassing freeloader. “Riff raff”, says Doc, dismissing the character as below their own class. Champ is the first to knock on the door. A voice inside welcomes him, but mistakenly addresses him as “the new doorman from the agency”. Champ is ushered in, but as an employee, and instructed to keep out all freeloaders. Forgetting everything about his friendship with Doc, Champ is swept up in living up to his new doorman role – so that, when Doc also knocks, presuming “We’re in”, he receives a chomp on the arm from the jaws of Champ. Champ spits Doc out on the patio, and when Doc asks why the heave-ho, is addressed by Champ as a “freeloader”, with the door then slammed in Doc’s face. Doc tries again, reminding Champ that they’re old friends. Champ responds by stuffing Doc down a drainpipe, then blowing through the pipe to launch Doc to the street below.

Doc tries disguise, slipping in underneath the wide ballroom skirt of one of the ladies. When he emerges at the dining table, and seeks to partake of the candied baby grasshoppers, Champ stuffs an apple in Doc’s mouth, places him under glass on a serving tray, and dumps the whole tray down the drain pipe again. Still regaining his elegant temperament, Doc remarks in the gutter below, “This should make a man lose his temper.” But a stroke of genius hits Doc, as he spots a long length of rubber hose resting against an alley fence. This, he declares, should solve his dinner problem.

To the strains of music suggesting a snake charmer, the hose end slithers under the door of the penthouse. Champ at first can’t figure out what it means, as the hose end rises to the dinner table, and begins syphoning-out the contents of a punch bowl under the door. Just outside the door, Doc reclines, drinking down the punch in savoring sips. Next, some sandwiches. With a powerful inhale, Doc begins a parade of sandwich slices and pitted olives, which all march their way in alternating columns into the hose. Now, a roast chicken, which rises from the plate and parades into the hose. Its still-marching shape disappears under the door, then returns, marching in the opposite direction. But as it emerges from the hose end, we see it is now only the skeleton, with all meat removed, and crumbles on the floor. Borrowing a dialog line common to Goofy from Hannah’s memory, Champ declares, “Somethin’ wrong here.” As a Corona Corona cigar disappears down the hose, Champ grabs the hose end, and speaks into it, reminding whoever is on the other side, “You forgot your dessert.” Doc acknowledges this oversight, and Champ provides his own idea of a finish – a lit stick of dynamite stuffed into the hose. Doc’s suction brings the unwanted final course to his mouth, but the fuse has not yet burned through to the explosive. So Doc turns the tables, stuffing the stick back into the hose, and blowing it back to Champ. He plugs his ears, as an explosion from inside blasts away the penthouse door. Inside, Champ is sprawled in a heap atop the wrecked dinner table, with the food scattered everywhere. “Throw that rowdy out,” calls a voice inside. “He’s a freeloader.” Looking briefly in the doorway, Doc, retaining his usual poise, remarks with mild disdain, “Freeloader. How disgusting” – then turns gracefully, making his exit back to his home alley.

To the strains of music suggesting a snake charmer, the hose end slithers under the door of the penthouse. Champ at first can’t figure out what it means, as the hose end rises to the dinner table, and begins syphoning-out the contents of a punch bowl under the door. Just outside the door, Doc reclines, drinking down the punch in savoring sips. Next, some sandwiches. With a powerful inhale, Doc begins a parade of sandwich slices and pitted olives, which all march their way in alternating columns into the hose. Now, a roast chicken, which rises from the plate and parades into the hose. Its still-marching shape disappears under the door, then returns, marching in the opposite direction. But as it emerges from the hose end, we see it is now only the skeleton, with all meat removed, and crumbles on the floor. Borrowing a dialog line common to Goofy from Hannah’s memory, Champ declares, “Somethin’ wrong here.” As a Corona Corona cigar disappears down the hose, Champ grabs the hose end, and speaks into it, reminding whoever is on the other side, “You forgot your dessert.” Doc acknowledges this oversight, and Champ provides his own idea of a finish – a lit stick of dynamite stuffed into the hose. Doc’s suction brings the unwanted final course to his mouth, but the fuse has not yet burned through to the explosive. So Doc turns the tables, stuffing the stick back into the hose, and blowing it back to Champ. He plugs his ears, as an explosion from inside blasts away the penthouse door. Inside, Champ is sprawled in a heap atop the wrecked dinner table, with the food scattered everywhere. “Throw that rowdy out,” calls a voice inside. “He’s a freeloader.” Looking briefly in the doorway, Doc, retaining his usual poise, remarks with mild disdain, “Freeloader. How disgusting” – then turns gracefully, making his exit back to his home alley.

• “Freeloading Feline” is at Archive.org

Pest of Show (Lantz/Universal, 2/62 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – Doc is today trying to introduce a little culture into Champ’s life, introducing him to the art of painting. Actually, Doc is doing all the brushwork, while Champ is forced to pose as model, wearing a ballet tutu. Champ asks Doc to hurry up and finish, as this is embarrassing. Indeed it is, as two observing alley cats begin to shout teases and insults at Champ, calling his behavior “la de da”, and asking him if he wants to play a game of “drop the hankie”. In a thought-cloud image, a fight bell goes off inside Champ’s head, and he leaps into a brawl with the two felines, which fight travels until Champ intercepts Doc’s canvas, poking his head right through it where the ballet dancer’s face should be. Doc moans, “You rowdy”, while Champ responds that dogs are supposed to chase cats. Doc insists that culture can only be acquired by suppressing your “Pagan instincts”.

Pest of Show (Lantz/Universal, 2/62 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – Doc is today trying to introduce a little culture into Champ’s life, introducing him to the art of painting. Actually, Doc is doing all the brushwork, while Champ is forced to pose as model, wearing a ballet tutu. Champ asks Doc to hurry up and finish, as this is embarrassing. Indeed it is, as two observing alley cats begin to shout teases and insults at Champ, calling his behavior “la de da”, and asking him if he wants to play a game of “drop the hankie”. In a thought-cloud image, a fight bell goes off inside Champ’s head, and he leaps into a brawl with the two felines, which fight travels until Champ intercepts Doc’s canvas, poking his head right through it where the ballet dancer’s face should be. Doc moans, “You rowdy”, while Champ responds that dogs are supposed to chase cats. Doc insists that culture can only be acquired by suppressing your “Pagan instincts”.

Doc spots a poster on the wall, giving him all the more motivation to see Champ become cultured – an ad for an upcoming dog show, with a banquet for winners. Doc vows to mold him into a champion. Champ immediately thinks he’s going back into the ring, until Doc explains that he will be a champion in the doggie set. A montage of scenes shows Doc giving Champ head to toe scrubbing, back massage in the manner of a fight trainer, teaching Champ to walk gracefully with a book balanced on his head, and other exercises in gracefulness. As the big night approaches, Doc supplies Champ with a large red bow to wear around his neck. The two alley cats look in at the window, and begin poking fun again, calling Champ “Priscilla”, and remarking “Now they got him gift-wrapped.” Before Champ can blow a fuse again, Doc pulls a windowshade down to block view of the cats, and mutters to himself, “Rowdies.”

Champ is enrolled in the show as “Baron De Tin Can Alley, Champion Punchwell the Fourth”. Champ attempts to befriend a few of the other dog competitors, but finds the Chihuahua taking a siesta under his hat, the British bulldog a bit too snooty, and a bit of a language barrier in communicating with the female French poodle. The judging begins, in three categories. First, physical perfection. Champ thinks this is right up his alley, and blows his culture training, by posing for the crowd in muscle-builder poses, and flexing his arms and pecs. Aghast, Doc covers his eyes, and mumbles to himself, “The jig is up.” But the audience seems to like it, and applauds. Next category: Personality. Grabbing a straw hat from nowhere, Champ portrays both roles of a Vaudeville comedy duo, using the worn-out wheeze of a joke, “Why did the chicken cross the road?” It gets a laugh! Pop-eyed, open jawed Doc can only mutter, “I don’t believe it.” Finally, obedience. Champ finally remembers one thing from his training, and strikes a perfect pointer pose on the stage. Doc is finally convinced “We’re in the money”, and advances to the stage to accept the winner’s cup. But who should show up on the sidelines again to razz the victor, but the two alley cats. They extend a feather on the end of a long pole to tickle Champ’s nose, in attempt to induce a sneeze to spoil his pose. Champ never quite reaches the sneeze – but the fight bell again goes off inside his head. The brawl is on. The poodle, Chihuahua, and bulldog find themselves rooting for the brawler in his battle against the felines, but a human voice is heard to shout, “Call the police”. This is Doc’s cue to exit the hall to not get involved in what is to follow. With a sigh, he resolves, “Once a rowdy, always a rowdy”, and saunters away as usual down the street.

Champ is enrolled in the show as “Baron De Tin Can Alley, Champion Punchwell the Fourth”. Champ attempts to befriend a few of the other dog competitors, but finds the Chihuahua taking a siesta under his hat, the British bulldog a bit too snooty, and a bit of a language barrier in communicating with the female French poodle. The judging begins, in three categories. First, physical perfection. Champ thinks this is right up his alley, and blows his culture training, by posing for the crowd in muscle-builder poses, and flexing his arms and pecs. Aghast, Doc covers his eyes, and mumbles to himself, “The jig is up.” But the audience seems to like it, and applauds. Next category: Personality. Grabbing a straw hat from nowhere, Champ portrays both roles of a Vaudeville comedy duo, using the worn-out wheeze of a joke, “Why did the chicken cross the road?” It gets a laugh! Pop-eyed, open jawed Doc can only mutter, “I don’t believe it.” Finally, obedience. Champ finally remembers one thing from his training, and strikes a perfect pointer pose on the stage. Doc is finally convinced “We’re in the money”, and advances to the stage to accept the winner’s cup. But who should show up on the sidelines again to razz the victor, but the two alley cats. They extend a feather on the end of a long pole to tickle Champ’s nose, in attempt to induce a sneeze to spoil his pose. Champ never quite reaches the sneeze – but the fight bell again goes off inside his head. The brawl is on. The poodle, Chihuahua, and bulldog find themselves rooting for the brawler in his battle against the felines, but a human voice is heard to shout, “Call the police”. This is Doc’s cue to exit the hall to not get involved in what is to follow. With a sigh, he resolves, “Once a rowdy, always a rowdy”, and saunters away as usual down the street.

Corny Concerto (Lantz/Universal, 10/62 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – Being short of ready cash, Doc once again trains Champ for a comeback in the ring. Champ goes through his usual routine with the punching bag, but this time knocks the bag right off its tether, with the round wooden framework which supported the bag falling upon Champ’s head. Doc produces a hammer, and declares he’ll have the problem fixed in a jiffy. Champ holds up the mounting board to the two-by-four to which it was originally attached, and Doc raises his arm to hammer in a nail from above. The head of the hammer disconnects from its handle, and despite Doc’s warning to look out, lands heavily upon Champ’s foot. Champ begins to hop around in pain, and moan in indecipherable gibberish. A passing beatnik dog, owner of a nearby coffee house, overhears the goings on, and peers over the fence. “Wow. Crazy. Listen to that cat wail.” He begins accompanying Champ, beating out a bongo rhythm on a nearby ash can. The beatnik declares he’d like to book Champ in his coffee house, adding “We’ll make a fortune”. Enough said to obtain Doc’s handshake in agreement. Doc receives the business card of the establishment “The Hungry Me – where the beat love to meet.” (Pun on a well-known real life beatnik locale, the Hungry I, located in San Francisco.)

Corny Concerto (Lantz/Universal, 10/62 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – Being short of ready cash, Doc once again trains Champ for a comeback in the ring. Champ goes through his usual routine with the punching bag, but this time knocks the bag right off its tether, with the round wooden framework which supported the bag falling upon Champ’s head. Doc produces a hammer, and declares he’ll have the problem fixed in a jiffy. Champ holds up the mounting board to the two-by-four to which it was originally attached, and Doc raises his arm to hammer in a nail from above. The head of the hammer disconnects from its handle, and despite Doc’s warning to look out, lands heavily upon Champ’s foot. Champ begins to hop around in pain, and moan in indecipherable gibberish. A passing beatnik dog, owner of a nearby coffee house, overhears the goings on, and peers over the fence. “Wow. Crazy. Listen to that cat wail.” He begins accompanying Champ, beating out a bongo rhythm on a nearby ash can. The beatnik declares he’d like to book Champ in his coffee house, adding “We’ll make a fortune”. Enough said to obtain Doc’s handshake in agreement. Doc receives the business card of the establishment “The Hungry Me – where the beat love to meet.” (Pun on a well-known real life beatnik locale, the Hungry I, located in San Francisco.)

Champ opens for his first night, with Doc playing an introductory piano obbligato, then whacking Champ on the foot with the hammer. A table of beatnik dogs snap their fingers to the “wailing” appreciatively, and, while hardly moving any other muscle, remark lazily, “Going”, “Going”, “Real gone.” The club owner declares this is a sure sign they’re crazy over Champ. (If this plot is beginning to sound familiar, as in Fred Flintstone’s invention of the dance “The Frantic” in “Shinrock a Go Go”, it seems highly likely that one Hanna cannibalized the concept from the other Hannah within a few short years.)

Champ’s act moves to Broadway. His aching foot now is wrapped in bandages, but still responds as Doc whacks it with a new, 24 karat gold hammer. Now, on to Carnegie Hall, where his act is billed as “Ow-oo-ee-oow”. But Champ can see this night isn’t going to go as expected, as Doc brings in not just a hammer, but a jumbo-sized mallet. As Doc concludes his piano notes and swings the mallet behind him, all that is heard is the dull thud of wood against wood. Champ has dodged the blow. Doc tries again, aiming for the other foot, but Champ again raises it away. Doc gets down on his hands and knees, whacking away, but Champ gingerly dances, keeping both feet out of reach. “This is embarrassing”, remarks Doc. The mallet end breaks off entirely, leaving Doc without a weapon. Champ retreats into a wardrobe closet, and Doc opens the door to find him dressed to impersonate Wagner’s Brunhilde. The disguise almost fools Doc, but Champ accidentally swings a prop axe he is holding against a rope supporting a heavy sandbag in the rafters. The bag falls on Champ’s foot, and the resulting wailing gives him away. Doc orders Champ back on stage. But Champ is no longer taking orders, pushing Doc into the wall, and announcing he is quitting show business. Doc pretends to plead for Champ’s cooperation by clutching his leg, adding to the audience that Champ always falls for this kind of thing. When Champ still won’t relent, and is about to depart, Doc declares that Champ needn’t worry, as he won’t be bothered by Doc anymore. This doesn’t sound right to Champ, and he looks back to find out what Doc means. Doc is holding a gun to his own head! Now it’s Champ who’s clutching Doc’s leg, begging him to reconsider, with Champ declaring that he was only fooling, and would never leave Doc. Doc turns the gun away from his temple, then, for the benefit of the audience’s view only, pulls the trigger – revealing only a pop-out flag emerging from the barrel, reading “Bang”.

Champ’s act moves to Broadway. His aching foot now is wrapped in bandages, but still responds as Doc whacks it with a new, 24 karat gold hammer. Now, on to Carnegie Hall, where his act is billed as “Ow-oo-ee-oow”. But Champ can see this night isn’t going to go as expected, as Doc brings in not just a hammer, but a jumbo-sized mallet. As Doc concludes his piano notes and swings the mallet behind him, all that is heard is the dull thud of wood against wood. Champ has dodged the blow. Doc tries again, aiming for the other foot, but Champ again raises it away. Doc gets down on his hands and knees, whacking away, but Champ gingerly dances, keeping both feet out of reach. “This is embarrassing”, remarks Doc. The mallet end breaks off entirely, leaving Doc without a weapon. Champ retreats into a wardrobe closet, and Doc opens the door to find him dressed to impersonate Wagner’s Brunhilde. The disguise almost fools Doc, but Champ accidentally swings a prop axe he is holding against a rope supporting a heavy sandbag in the rafters. The bag falls on Champ’s foot, and the resulting wailing gives him away. Doc orders Champ back on stage. But Champ is no longer taking orders, pushing Doc into the wall, and announcing he is quitting show business. Doc pretends to plead for Champ’s cooperation by clutching his leg, adding to the audience that Champ always falls for this kind of thing. When Champ still won’t relent, and is about to depart, Doc declares that Champ needn’t worry, as he won’t be bothered by Doc anymore. This doesn’t sound right to Champ, and he looks back to find out what Doc means. Doc is holding a gun to his own head! Now it’s Champ who’s clutching Doc’s leg, begging him to reconsider, with Champ declaring that he was only fooling, and would never leave Doc. Doc turns the gun away from his temple, then, for the benefit of the audience’s view only, pulls the trigger – revealing only a pop-out flag emerging from the barrel, reading “Bang”.

Doc and Champ thus return their act to the original venue at “The Hungry Me”. Champ appears on stage as promised. But when the crucial moment arrives after the last piano note, there is a switch. Champ grabs the hammer from Doc’s grip, and uses it to smack Doc soundly on the toe. Now it’s Doc hopping and wailing. The audience is just as happy as before, and the club owner closes with the remark, “Man, like this cat’s better than the other one.”

• Walter Lantz’ “Corny Concerto” is at Archive.org

A film which seems to have shown up on several bloggers’ worst cartoon lists is Op Pop Wham and Bop (Paramount, 1966 – Howard Post, dir.). It attempts to get some titters from the concept of a visit to a “pop” or “op” art museum – a new fad of the day with objects that often resembled giant versions of everyday objects, household appliances, etc. and paintings that did likewise. Disney would make much better and funnier use of the concept a few years later, in the Dick Van Dyke/Edward G. Robinson comedy, “Never a Dull Moment”.

A film which seems to have shown up on several bloggers’ worst cartoon lists is Op Pop Wham and Bop (Paramount, 1966 – Howard Post, dir.). It attempts to get some titters from the concept of a visit to a “pop” or “op” art museum – a new fad of the day with objects that often resembled giant versions of everyday objects, household appliances, etc. and paintings that did likewise. Disney would make much better and funnier use of the concept a few years later, in the Dick Van Dyke/Edward G. Robinson comedy, “Never a Dull Moment”.

This film is perhaps a bit more palatable in the viewing if one forgets that its principal characters are supposed to be a new pair named Ffat Kat and Rat Ffink – just remember the studio who produced this, and imagine it to be a script for Herman and Katnip. The mouse of the piece even resembles Herman in several respects, though neither character is provided with a voice. We open at the “Museum of Way Out Art”, part of which’s outer structure looks like a giant potted plant with equal-scale watering can. Ffat Kat is found sleeping within a supposedly flat picture of a window with drawn windowshade, raising the shade to emerge and stretch, ready for his morning meal. He passes several paintings, obtaining fish, ham, and something to drink right out of the flat images, somehow making them into real-life 3D edibles. He reaches a still life of a hunk of cheese on a table, and extracts the cheese for his plate – but the cheese leaps back onto the painting, several times. Finally getting a firm grip upon the wedge, the cat discovers the reason the cheese was unwilling to come along – the mouse is already inside it. In the same manner as Herman might have done in the old days, Herman whacks the cat across the face with his own fish, knocking him into a Salvador Dali-like sculpture, where he seems to become part of the artwork, with the fish still slapping him across the face.

An endless series of chase gags follows, with the characters hopping in and out of paintings, and using props from same against each other. Some gags are as old as the hills, with a telephone call “It’s for you” gag, and a picture of waves moved behind a porthole for seasickness. A little better result comes from passing a cartoon bomb retrieved from a painting in a game of in and out the window between a painting doorway and a mousehole swinging door, finishing with an unexpected change of direction in passing the bomb, leaving the explosive placed atop the cat’s head. A sculpture is converted into a guillotine, almost resulting in the cat’s beheading. (Told you this was a disguised Herman and Katnip.) Finally, the cat encounters a painting that appears to have multiple images of the mouse (though, showing the cheapness of the product, the artists can only afford to depict the mouse eight times, removing all impact from the last gag). Assuming one of them has to be the real mouse, the cat starts punching holes in the canvas with his fist wherever the mouse appears. In reality, the mouse is within another painting on a side wall, munching his cheese and watching the fun. If the studio had been able to draw an image where the mouse appeared hundreds of times, to give the impression the cat will be busy punching all day, the gag might have worked. But with only eight punches to make before he runs out of targets, what’s the point of the routine, as the cat will get wise soon enough. Abruptly, the film ends there, after running not a second past six minutes, seemingly over before it begins. Well, maybe not having to endure more sequences was merciful.

An endless series of chase gags follows, with the characters hopping in and out of paintings, and using props from same against each other. Some gags are as old as the hills, with a telephone call “It’s for you” gag, and a picture of waves moved behind a porthole for seasickness. A little better result comes from passing a cartoon bomb retrieved from a painting in a game of in and out the window between a painting doorway and a mousehole swinging door, finishing with an unexpected change of direction in passing the bomb, leaving the explosive placed atop the cat’s head. A sculpture is converted into a guillotine, almost resulting in the cat’s beheading. (Told you this was a disguised Herman and Katnip.) Finally, the cat encounters a painting that appears to have multiple images of the mouse (though, showing the cheapness of the product, the artists can only afford to depict the mouse eight times, removing all impact from the last gag). Assuming one of them has to be the real mouse, the cat starts punching holes in the canvas with his fist wherever the mouse appears. In reality, the mouse is within another painting on a side wall, munching his cheese and watching the fun. If the studio had been able to draw an image where the mouse appeared hundreds of times, to give the impression the cat will be busy punching all day, the gag might have worked. But with only eight punches to make before he runs out of targets, what’s the point of the routine, as the cat will get wise soon enough. Abruptly, the film ends there, after running not a second past six minutes, seemingly over before it begins. Well, maybe not having to endure more sequences was merciful.

Though not quite a custom fit to our subject topic, honorable mention goes to Rock ‘n Rodent (Chuck Jones/MGM. Tom and Jerry, 4/7/67 – Abe Levitow, dir.), for steering its starring characters into modern trends. Jerry, a drummer in a hot contemporary jazz band in a posh “beat” nightclub for mice? Yes, it really happens. Jerry has come full circle from the party-pooper who tried to break up Tom’s jam session in “Saturday Evening Puss” in favor of a little sleep, and now, he’s the one with a yen for the downbeat, with Tom the tired individual who just longs for a lick of sleep. Some of the setup is clever. While Tom sets a conventional alarm clock to ring in the morning and beds down in his cat basket, Jerry, inside his mousehole sleeps in a bed actually built into the satin-lined jewelry case of a ladies’ wristwatch, and uses the watch surrounding him as his alarm to let him know it is time to rise and shine for tonight’s performance. With the aid of some strings tied to a monkey-wrench applied to a pipe joint in the wall, Jerry tugs to produce a quick wake-up shower, and is soon ready for his night at the club. His and Tom’s apartments are high in the penthouse of a skyscraper-like building, and Jerry gets to his place of employment by a small mousehole-sized elevator next to his regular hole, which allows him to descend deep into the sub-floors of the tower, to a club called “Le Cellar Smogue”. Before mounting the bandstand, Jerry gets lubricated for the night by visiting the bar, where a mouse bartender whips him up what appears to be a mouse martini, but is topped with a small piece of Swiss cheese on a toothpick instead of an olive. Jerry proves to be only mildly alcoholic, removing the toothpick and consuming the alcohol-soaked morsel of Swiss, but leaving the drink behind – with the bartender swallowing it himself when no one’s looking. Then, Jerry seats himself at a miniature full drum set, alongside other musician mice who have the look of beatnik society and/or the mildly psychedelic wardrobes of the ‘60’s, and the music commences. Drums beat, trumpets wail, and one girl mouse in the audience’s hairdo starts doing a swiveling dance to the rhythm all by itself. The scenes of Jerry are from this point on presented in many varieties of multicolored mood lighting that renders the characters opaque against the layers of color, also giving the visuals a somewhat psychedelic, trippy appearance.

Though not quite a custom fit to our subject topic, honorable mention goes to Rock ‘n Rodent (Chuck Jones/MGM. Tom and Jerry, 4/7/67 – Abe Levitow, dir.), for steering its starring characters into modern trends. Jerry, a drummer in a hot contemporary jazz band in a posh “beat” nightclub for mice? Yes, it really happens. Jerry has come full circle from the party-pooper who tried to break up Tom’s jam session in “Saturday Evening Puss” in favor of a little sleep, and now, he’s the one with a yen for the downbeat, with Tom the tired individual who just longs for a lick of sleep. Some of the setup is clever. While Tom sets a conventional alarm clock to ring in the morning and beds down in his cat basket, Jerry, inside his mousehole sleeps in a bed actually built into the satin-lined jewelry case of a ladies’ wristwatch, and uses the watch surrounding him as his alarm to let him know it is time to rise and shine for tonight’s performance. With the aid of some strings tied to a monkey-wrench applied to a pipe joint in the wall, Jerry tugs to produce a quick wake-up shower, and is soon ready for his night at the club. His and Tom’s apartments are high in the penthouse of a skyscraper-like building, and Jerry gets to his place of employment by a small mousehole-sized elevator next to his regular hole, which allows him to descend deep into the sub-floors of the tower, to a club called “Le Cellar Smogue”. Before mounting the bandstand, Jerry gets lubricated for the night by visiting the bar, where a mouse bartender whips him up what appears to be a mouse martini, but is topped with a small piece of Swiss cheese on a toothpick instead of an olive. Jerry proves to be only mildly alcoholic, removing the toothpick and consuming the alcohol-soaked morsel of Swiss, but leaving the drink behind – with the bartender swallowing it himself when no one’s looking. Then, Jerry seats himself at a miniature full drum set, alongside other musician mice who have the look of beatnik society and/or the mildly psychedelic wardrobes of the ‘60’s, and the music commences. Drums beat, trumpets wail, and one girl mouse in the audience’s hairdo starts doing a swiveling dance to the rhythm all by itself. The scenes of Jerry are from this point on presented in many varieties of multicolored mood lighting that renders the characters opaque against the layers of color, also giving the visuals a somewhat psychedelic, trippy appearance.

The blaring volume, and especially the beat of Jerry’s drum, rises up the elevator shaft, pounding upon the eardrums of Tom, for a jarring awakening. Stuffing a pillow in the elevator door won’t hold back the sound, which blasts the pillow apart, scatters feathers all over the room, and leaves Tom embedded in the plaster of the opposite wall. Tom inserts an emergency fire hose nozzle in the elevator shaft, and turns the water on full force. A few moments later, he is seized by the throat of a bulldog, a tenant of an apartment far below, who drags Tom downstairs, and shoves him into the door of the dog’s apartment – into a room entirely flooded by Tom’s water. Returning to his own apartment drenched, Tom removes a grating from a ventilation shaft, crawls down the shaft armed with a toolbox, and winds up in a basement, where he attempts to locate the source of the music. Hearing a blaring horn just above the ceiling, Tom cuts a hole through, and uses a plunger in attempt to seize the musician. All he gets is a transistor radio, and a pounding from the same bulldog, into whose apartment he has intruded again. The bulldog delivers an upper-cut to Tom’s jaw, launching him all the way back upstairs, and through the floor under Tom’s own basket. Sensing that he has no way of finding and stopping the performance, Tom’s resorts to the only self-defense he can think of – plugging champagne corks into both ears, and wrapping his head up completely in gauze bandages. The trumpets below reach a crescendo – and the number ends. Tom’s eyes pop open. All is quiet. Tom tests the situation, dropping a pin on a table, which is heard with a tinny clank. In crazed disbelief at the total silence, Tom removes the bandages and corks, and begins to quickly drop off to sleep. At the elevator hole, Jerry, weary from a hard night’s work, also returns yawning, entering his mousehole. It seems all will finally end well – until Tom’s alarm clock suddenly goes off. Tom can’t seem to find the button to shut it off, and irritated Jerry shushes him from the mousehole. Unable to stop the ringing, Tom goes mad, screams, and bursts through the apartment wall, plunging out of the skyscraper into thin air against a skyline background. Jerry just shrugs his shoulders to the camera at the unexplained breakdown of the cat, and makes an exit back into his mousehole in the surprise manner of a Charlie Chaplin walk, shutting the light for his own good night’s sleep.

The blaring volume, and especially the beat of Jerry’s drum, rises up the elevator shaft, pounding upon the eardrums of Tom, for a jarring awakening. Stuffing a pillow in the elevator door won’t hold back the sound, which blasts the pillow apart, scatters feathers all over the room, and leaves Tom embedded in the plaster of the opposite wall. Tom inserts an emergency fire hose nozzle in the elevator shaft, and turns the water on full force. A few moments later, he is seized by the throat of a bulldog, a tenant of an apartment far below, who drags Tom downstairs, and shoves him into the door of the dog’s apartment – into a room entirely flooded by Tom’s water. Returning to his own apartment drenched, Tom removes a grating from a ventilation shaft, crawls down the shaft armed with a toolbox, and winds up in a basement, where he attempts to locate the source of the music. Hearing a blaring horn just above the ceiling, Tom cuts a hole through, and uses a plunger in attempt to seize the musician. All he gets is a transistor radio, and a pounding from the same bulldog, into whose apartment he has intruded again. The bulldog delivers an upper-cut to Tom’s jaw, launching him all the way back upstairs, and through the floor under Tom’s own basket. Sensing that he has no way of finding and stopping the performance, Tom’s resorts to the only self-defense he can think of – plugging champagne corks into both ears, and wrapping his head up completely in gauze bandages. The trumpets below reach a crescendo – and the number ends. Tom’s eyes pop open. All is quiet. Tom tests the situation, dropping a pin on a table, which is heard with a tinny clank. In crazed disbelief at the total silence, Tom removes the bandages and corks, and begins to quickly drop off to sleep. At the elevator hole, Jerry, weary from a hard night’s work, also returns yawning, entering his mousehole. It seems all will finally end well – until Tom’s alarm clock suddenly goes off. Tom can’t seem to find the button to shut it off, and irritated Jerry shushes him from the mousehole. Unable to stop the ringing, Tom goes mad, screams, and bursts through the apartment wall, plunging out of the skyscraper into thin air against a skyline background. Jerry just shrugs his shoulders to the camera at the unexplained breakdown of the cat, and makes an exit back into his mousehole in the surprise manner of a Charlie Chaplin walk, shutting the light for his own good night’s sleep.

• “Rock n’ Rodent” is on DailyMotion.

A brief, not-so-honorable mention should also be made of Chiller Dillers (Walter Lantz/Universal. Chilly Willy, 12/1/67 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) in which, of all characters, Chilly Willy and Maxie the Polar Bear form a rock band. There is unfortunately little to say positive about the film, having no particular innovation, no surprise photographic effects, and a barely “bearable” musical number, the Mukluk Bop. The number seems to go on endlessly, appearing between every sequence. The plot has a sea captain trying to capture them to obtain a Hollywood contract – and no explanation is provided why Chilly declines to sign up with the captain, instead convincing Maxie to talk the captain into signing up a singing whale – whose voice is only provided by phonograph record inserted by Chilly into his belly. While Tom and Jerry’s effort had a little bit of stylistic class, Chilly’s looks like an absolute sell-out to the times – just a poor excuse to find a plot idea when none more fitting the character was available.

A brief, not-so-honorable mention should also be made of Chiller Dillers (Walter Lantz/Universal. Chilly Willy, 12/1/67 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) in which, of all characters, Chilly Willy and Maxie the Polar Bear form a rock band. There is unfortunately little to say positive about the film, having no particular innovation, no surprise photographic effects, and a barely “bearable” musical number, the Mukluk Bop. The number seems to go on endlessly, appearing between every sequence. The plot has a sea captain trying to capture them to obtain a Hollywood contract – and no explanation is provided why Chilly declines to sign up with the captain, instead convincing Maxie to talk the captain into signing up a singing whale – whose voice is only provided by phonograph record inserted by Chilly into his belly. While Tom and Jerry’s effort had a little bit of stylistic class, Chilly’s looks like an absolute sell-out to the times – just a poor excuse to find a plot idea when none more fitting the character was available.

• Should you choose to watch it, “Chiller Dillers” can be found at Archive.org. You’ve been warned.

Ralph Bakshi’s Marvin Digs (Paramount, 12/1/67), introduces theatrical animation to the flower-child theme (but then, wasn’t Ferdinand the Bull the original flower child?). The title character is depicted as a walking ball of hair resembling the Addams Family’s Cousin Itt, but with a trendier hat and shoes. He passes around flowers randomly – even to fighting alley cats and dogs. Most of the time he is misunderstood. His flowers wilt when two women call him a “fresh kid”. A policeman who “wants no trouble” develops a case of hay fever at his blooms. He is the ultimate disappointment to his dad (voiced by Dayton Allen), who thinks he has no drive and initiative – plus can’t even recognize him under the hair (“That’s a kid?”). While Marvin dreams psychedelic dreams of dancing with human-sized flowers who randomly become girls, Pop plans to delegate work to “make a man of him” – the project of painting the living room. Marvin’s friends are tripped out that he can’t join them for the usual schedule of “sit-ins”, “stand-ins”, “love-ins”, etc., but as Marvin brings home the paints, he hears a TV announcer discuss a city beautification program, encouraging the public to “treat their city like they would their own home”. Marvin gets an inspiration, and calls on his friends to join him for a “paint-in”. Dad awakes from an afternoon nap to find the living room painted in trippy multicolor designs. “Your mother’s going to kill us!”, he shouts. Marvin assures him that it goes great with the outside. Dad freaks out when he discovers Marvin and friends have painted the entire block in the same fashion. The police arrive, escorting the Mayor. While the populace is ready to vent a chorus of disapproving prejudice, the Mayor commends Marvin as a model citizen, showing true inspiration, originality and drive. “Drive?”, reacts his father, and suddenly recognizes Marvin as a credit to the family, ending the film with trying to draw forced analogies between Marvin and his own childhood to bask in the reflected credit – “When I was a boy…I was a boy once……” A stylish production, with some genuine trendy music by a group called The Life Cycle, interesting photographic effects, and, if not a wholly-committed treatment to solving the generation gap, at least a reasonable stab at approaching it with gentle humor and soft sell.

Ralph Bakshi’s Marvin Digs (Paramount, 12/1/67), introduces theatrical animation to the flower-child theme (but then, wasn’t Ferdinand the Bull the original flower child?). The title character is depicted as a walking ball of hair resembling the Addams Family’s Cousin Itt, but with a trendier hat and shoes. He passes around flowers randomly – even to fighting alley cats and dogs. Most of the time he is misunderstood. His flowers wilt when two women call him a “fresh kid”. A policeman who “wants no trouble” develops a case of hay fever at his blooms. He is the ultimate disappointment to his dad (voiced by Dayton Allen), who thinks he has no drive and initiative – plus can’t even recognize him under the hair (“That’s a kid?”). While Marvin dreams psychedelic dreams of dancing with human-sized flowers who randomly become girls, Pop plans to delegate work to “make a man of him” – the project of painting the living room. Marvin’s friends are tripped out that he can’t join them for the usual schedule of “sit-ins”, “stand-ins”, “love-ins”, etc., but as Marvin brings home the paints, he hears a TV announcer discuss a city beautification program, encouraging the public to “treat their city like they would their own home”. Marvin gets an inspiration, and calls on his friends to join him for a “paint-in”. Dad awakes from an afternoon nap to find the living room painted in trippy multicolor designs. “Your mother’s going to kill us!”, he shouts. Marvin assures him that it goes great with the outside. Dad freaks out when he discovers Marvin and friends have painted the entire block in the same fashion. The police arrive, escorting the Mayor. While the populace is ready to vent a chorus of disapproving prejudice, the Mayor commends Marvin as a model citizen, showing true inspiration, originality and drive. “Drive?”, reacts his father, and suddenly recognizes Marvin as a credit to the family, ending the film with trying to draw forced analogies between Marvin and his own childhood to bask in the reflected credit – “When I was a boy…I was a boy once……” A stylish production, with some genuine trendy music by a group called The Life Cycle, interesting photographic effects, and, if not a wholly-committed treatment to solving the generation gap, at least a reasonable stab at approaching it with gentle humor and soft sell.

Hurts and Flowers (DePatie-Freleng/UA, Roland and Rattfink, 2/11/69, Hawley Pratt, dir.) follows suit upon the ideas of “Marvin Digs”, casting the studio’s new hero and Dudley-Do-Right impersonator Roland as “a flower child”, and villainous Snydely Whiplash counterpart Rattfink as “a weed”. Much like Ferdinand, Roland sits lazily under a tree contemplating the flowers, and conjuring up visions of hearts labeled “Love”. Evil killjoy Rattfink shoots an arrow from a bow squarely into the heart, cracking it, and gives Roland the horse laugh.

Hurts and Flowers (DePatie-Freleng/UA, Roland and Rattfink, 2/11/69, Hawley Pratt, dir.) follows suit upon the ideas of “Marvin Digs”, casting the studio’s new hero and Dudley-Do-Right impersonator Roland as “a flower child”, and villainous Snydely Whiplash counterpart Rattfink as “a weed”. Much like Ferdinand, Roland sits lazily under a tree contemplating the flowers, and conjuring up visions of hearts labeled “Love”. Evil killjoy Rattfink shoots an arrow from a bow squarely into the heart, cracking it, and gives Roland the horse laugh.

Peaceful Roland does not retaliate, but offers Rattfink a flower. Disgusted, Rattfink folds the petals of the flower into the point of another arrow, and lets fly another volley – straight into Roland’s rear, and causing him to fall down a well. A drenched Roland still peacefully offers Rattfink another flower! A six minute theme-and-variation ensues, with Rattfink pulling his most evil dirty tricks on Roland, but Roland, bruised, battered, and blasted, still doing nothing but offering Rattfink a flower. Rattfink can’t get no satisfaction! He tries to toughen Roland up by making him inhale from a tank of “Evil Gas”. (I still can’t find this product in any supply house – even Amazon.) The trick works momentarily, but backfires as Roland pummels him. When the effects wear off, the same flower again! Roland finally performs as drummer in a light rock group. Rattfink paints a large can of nitro glycerine to look like a drum, and tries to make an instrument switch. But he slips on a banana peel, sending the drum flying into the air above him – and down. All that is left of Rattfink is a huge crater. In the only line of dialog in the film, Roland’s two co-musicians look into the crater while one remarks, “Man, like he had a bad trip!” The scene fades in on the gravestone of Rattfink. Roland appears and places a potted flower on the grave, then departs. The ghost of Rattfink rises from the grave, takes the pot, and hurls it at Roland. Roland is conked on the head and knocked to the ground, a lump rising from his scalp, from which grows another flower – as a flower-shaped iris out closes the scene amidst Rattfink’s ghostly laughter. Seems like Freleng and company may have had considerably different sentiments regarding flower children than Ralph Bakshi!

Peaceful Roland does not retaliate, but offers Rattfink a flower. Disgusted, Rattfink folds the petals of the flower into the point of another arrow, and lets fly another volley – straight into Roland’s rear, and causing him to fall down a well. A drenched Roland still peacefully offers Rattfink another flower! A six minute theme-and-variation ensues, with Rattfink pulling his most evil dirty tricks on Roland, but Roland, bruised, battered, and blasted, still doing nothing but offering Rattfink a flower. Rattfink can’t get no satisfaction! He tries to toughen Roland up by making him inhale from a tank of “Evil Gas”. (I still can’t find this product in any supply house – even Amazon.) The trick works momentarily, but backfires as Roland pummels him. When the effects wear off, the same flower again! Roland finally performs as drummer in a light rock group. Rattfink paints a large can of nitro glycerine to look like a drum, and tries to make an instrument switch. But he slips on a banana peel, sending the drum flying into the air above him – and down. All that is left of Rattfink is a huge crater. In the only line of dialog in the film, Roland’s two co-musicians look into the crater while one remarks, “Man, like he had a bad trip!” The scene fades in on the gravestone of Rattfink. Roland appears and places a potted flower on the grave, then departs. The ghost of Rattfink rises from the grave, takes the pot, and hurls it at Roland. Roland is conked on the head and knocked to the ground, a lump rising from his scalp, from which grows another flower – as a flower-shaped iris out closes the scene amidst Rattfink’s ghostly laughter. Seems like Freleng and company may have had considerably different sentiments regarding flower children than Ralph Bakshi!