Continuing my musings on Paul Terry and his characters. To read part 1 of this set, CLICK HERE.

Among Terry’s cast there is one superstar, and it’s not hard to guess who it is. Upon closer inspection, this character is no weirder than the rest of the regulars. Its origins date back to another passion of the Terry household: old movie serials in the style of “The Perils of Pauline” and operetta. How about combining the two? To tell the truth, this evocation of the naivety of the gay nineties was in the air in the 1930s. The Fleischer had done the same, and Mae West’s films prowled around the period. Terry’s take on it begins with 1933’s The Banker’s Daughter and, within the familiar villain-heroine-in-distress-hero triangle, introduces Oil Can Harry as the prototype of the feline who will be the future foil of our hero. Terry participates then in the ironic gaze of the era, having fun with the most absurd aspects of melodrama.

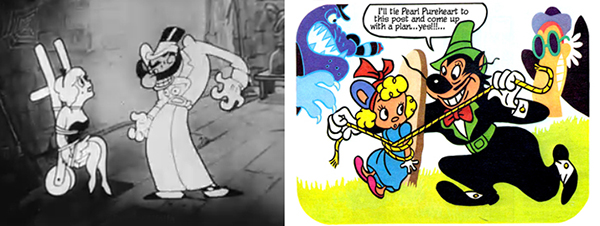

Oil Can Harry then and now. The final look is taken from a Miguel Gallardo comic based upon a Jim Tyer design.

At the same time, another of Terry’s passions was simmering: flying. In an article that appeared in Cartoon Research (more precisely, in the comments section), Gene Deitch recalls his only encounter with a now-retired Terry:

He did once invite me to lunch at a posh restaurant, loading me with his cartoon theories, mainly that Charles Lindbergh was the greatest hero in history, and that I should create a character modelled on Lindbergh. He forgot that the former hero of the first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean, who later earned the nation’s sympathy when his son was kidnapped and murdered, had blown it all by becoming a fervid supporter of Adolf Hitler! I could not fathom Terry’s adoration of Lindbergh at that time.

Given these observations, perhaps Gene wouldn’t be so surprised to see this cartoon (“In Venice”, 1933):

Beyond the eerie charm of watching Terry’s stars parading in black shirts, or the surprise of having Will Rogers stepping out of the Duce’s car, it is interesting to note the inclusion of Italo Balbo, the fascist Marshal of Air Forces, as a kind of Deus ex Machine capable of flying on his own. Balbo’s central role in this cartoon may seem strange, but the Italian was then the hero of the day, having just completed a transoceanic flight in his seaplane and made the cover of Time magazine. In any case, I am interested in the idea that Terry’s heroes fly—no strings attached—and did so even before Superman (paradoxically, both Rogers and Balbo would die in plane crashes).

A minor detail to note: Paul’s brother, John, who had a brief stint at the studio, ended his career as a comic strip artist. It was not a long career; John died of tuberculosis in 1934. His creation, Scorchy Smith (soon taken over by the brilliant Noel Sickles), starred an aviator modeled after Charles Lindbergh. Perhaps this vaguely sentimental fact explains why Terry proposed the 1927 hero as a prototype still viable in 1956.

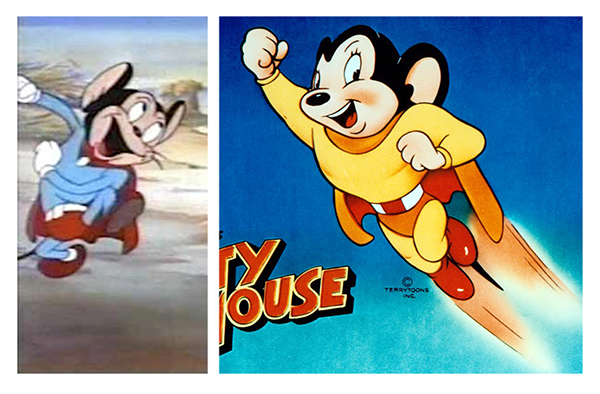

Add to this recipe Terry’s well-known passion for the cause of mice, a pinch of the growing popularity of superhero comic books, and we have Mighty Mouse. But Super Mouse, as it was originally called, continued the parodic tradition of its predecessors. It was meant to be funny. A quick comparison will reveal the differences between Supermouse and Mighty Mouse.

Super Mouse vs. Mighty Mouse

Because Mighty Mouse is “serious,” as serious as a mouse flying in underwear can be. There are several ingredients in it, too many even. Preserved are Pearl White and Oil Can Harry—turned into mouse and cat, respectively—the taste for old serials (the entries where the short alludes to previous episodes never produced rank among the best), operetta and flying. Irony, with a few exceptions, is left out: it is well known that child audiences do not appreciate this kind of intellectual boasting. But MM is not only serious, but even mysterious. Living on the moon, a cloud, or a star (mercifully, Terry spares us the scrupulous mythologies typical of Marvel), the mouse descends upon his people as a kind of savior, a Rodent Messiah with a flair for Gilbert and Sullivan. Sometimes he cries while flying, which is somewhat perplexing for a superhero. His enemies are no less strange: a tribe of cats with bat wings, witches with vulture faces, winged boars, flying tigers with Jerry Colonna’s mustache, dog planes and worse. The kind of visions that make you wonder if there’s a hidden clue somewhere or if the liquor was flowing freely in the studio.

MM foils (thanks to “Yowp”, from whose blog I extracted the following images)

Superman, his obvious model, set out to save the world. Our hero, much more modest, is content with saving the day. The difference is that the mouse usually succeeds.

Oh, and of course: this mouse always gets his girl.

Epilogue:

In short, if we leave aside the misfiring conditioned by the mechanics of production and the tastes of the times (nothing and no one can ever rescue Dinky Duck), Paul Terry’s continued output has all the characteristics of what we call an “oeuvre”.

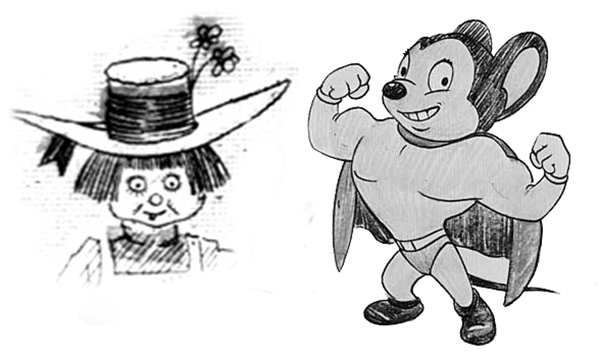

Left, a comic book character drawn by Paul Terry. Right: Final design by MM. Note the stylistic similarities. Old Paul must have been involved to some extent.

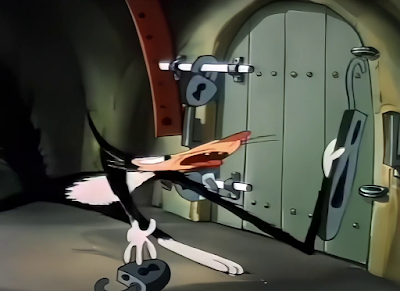

Of course, a huge amount of talent came together on it, although the lack of general information about the studio’s activities often makes it difficult to know who did what. This shortcoming is often compensated for by the intuition of viewers. For example, this drawing below must undoubtedly come from “that guy from Van Beuren.”

The Guy From Van Beuren

One criticism that deserves reconsideration concerns the reuse of animations from one short film to another due to production deadlines (one cartoon per week). The undeniable economic basis for this gimmick should not prevent us from seeing one important detail: Catnip Capers from 1940, Somewhere in Egypt from 1943, and King Tut’s Tomb from 1950, to mention one example, feature the same dancing kitten (courtesy of Carlo Vinci), except that it’s not exactly the same—the 1940 dance is refined to the paroxysm in the 1943 film. This was how an obsessive artist like Carlo Vinci could adapt his incredible skills to Terry’s production mechanics, which did not exactly match Disney’s schedule, perfecting his work in front of the audience. On the other hand, some of the gags in Somewhere in Egypt can be traced back to Gypped in Egypt (Van Beuren, 1930. John Foster worked on both films), while the shot of the cats on the kettledrums dates back to Hot Turkey a 1930 Terrytoon. As I said, it’s almost impossible to know what belongs to whom. May I be talking about Foster’s obsessions when I refer to Terry? And what about Jerry Shields’ delusions? We don’t really know anything about these people. Even an artist as refined as Frank Moser is little more than a shadow today. The only thing that is certain is that Terry used the available talent in a liberal way that was unprecedented for his time, and for anyone else’s. I can’t imagine any other studio allowing the wonderful maverick Jim Tyer so much freedom for so long.

Tyer.

I’m far from being an expert (most of what I know I owe to the commendable educational efforts of Milton Knight and his colleagues on YouTube), but this article does not claim to be an exhaustive list of Terrytoons artists: for that we would need one of those lavish pieces brimming with quotes, photos, and pictures that adorn the most select coffee tables and that perhaps exist somewhere. What is certain is that research into Terry and his work, when it could still be done, suffered from the general contempt that, by continuous repetition, became now almost commonplace. Even the sensitive Gene Deitch, when talking about his time at the studio, refers to “the vast library of previously produced mediocre Terrytoons cartoons”. This little slip—Deitch, wearing UPA blinders, could not really see what was in front of him—is not attributable to anyone’s particular short-sightedness but only a sign of the times; and ours are no better. The real drama is that it is too late to find out much more.

Paul Terry today

Meanwhile, the ideas of Terry and his team remain floating in the air, available to those who have eyes and something connected to these gadgets. Because here in Argentina, we have watched Terrytoons closely. Carefully. This can happen in the best families. Even in mine.

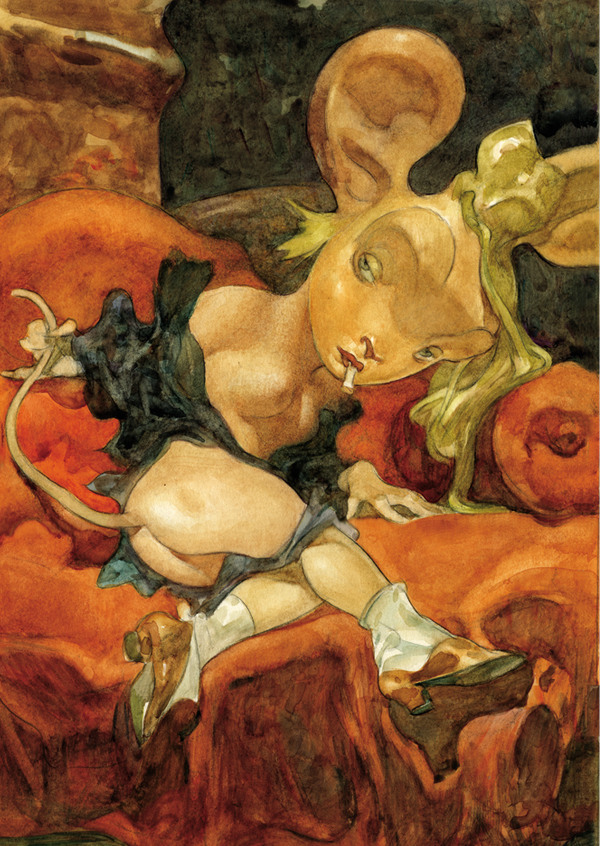

A drawing by Carlos Nine, taken from his last graphic novel, “Tropikal Mambo.”

ABOVE: “Creole Love Call”, 2002, directed by Carlos Nine and animated by Santiago Nine.