Paul Terry is an evanescent figure, not to say elusive, not to say non-existent. There is not much written about him, and even less in the form of those extensive interviews in which monsters such as Kimball or Hubley discuss their careers, peppering them with a thousand real or imagined details. Trying to gather material on the man is a task probably doomed to failure, beyond a couple of articles written in a dubious first person for mass-circulation magazines. The first mentions I read about a flesh-and-blood being named Paul Terry were not very promising either. In Donald Crofton’s “Before Mickey,” he appears a couple of times. First, he is told that the film used for one of his early cartoons was worth more before he left his mark on it, and then he is informed that his films are good enough to allow him to buy one of Bray’s animation patents—or else.

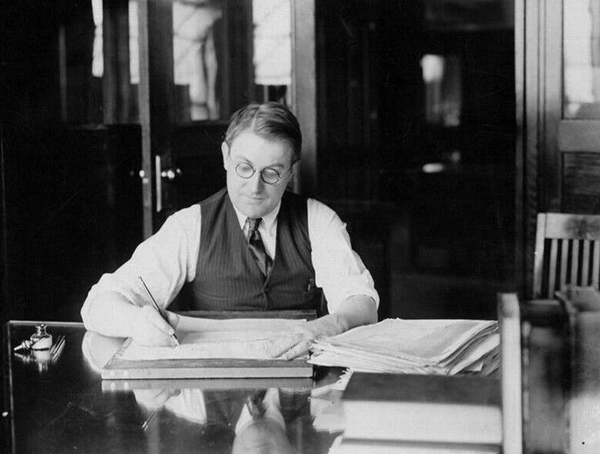

Thousands of books have been written about Walt Disney and his troupe, explaining even the slightest nuances of the Marceline Master’s eyebrow twitches. The different codes transmitted by the nervous drumming of his fingers have been deciphered by specialists in the Rosetta stone, while all ashtrays in Burbank were combed through exhaustively. Terry, on the other hand, is a blank page. His few photos show the kind of magnetism needed to star in “Death of a Salesman”. After seeing Disney strutting around in his luxurious office, it is inevitable to imagine how such an environment would look in Terry’s case: gray linoleum floor, a library limited to the phone book and no Rembrandt portrait of Mighty Mouse on the wall.

Of course, it’s Paul “Woolworth” Terry himself the main responsible for this image of a hardware store clerk that accompanied him until the end of his days, or at least until the day he sold the studio, mumbling farewell to his staff as he fled on tiptoe. The general view makes him out to be a tough businessman, with not many dollars, fewer scruples, and the motto “quantity over quality” tattooed on the neck. And if, by some miracle, talented people came to work for him, the mistake was quickly corrected by the studio’s status quo.

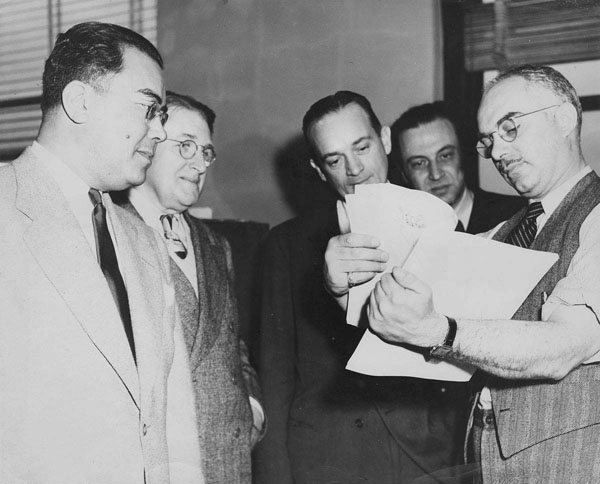

Terry and Carlo Vinci (flipping at right)

In any case, the general consensus prevents Terry from being taken, even remotely, for anything resembling an “author” or someone with ideas of his own beyond churning out the stuff. And yet, a set of themes and motifs seem to recur in his work with such regularity that one would be tempted to call it “authorial.” Given the man status, it is easy to attribute this exclusively to his staff, people who generally received even less press coverage than Paul himself. The only problem is that themes are repeated over periods of time that transcend Terry’s association with these artists.

Therefore, my goal is to draw up a brief list of recurring motifs in the Terryan corpus , rather than attempting to organize some guiding thesis that would structure it (a folly beyond my powers). I would be satisfied with just managing to record a sum of perplexities: those that made me take a special interest in the Terry of my childhood TV, which other celebrities, authors of more resounding fame, could never aspire to. The thing is, Terry was weird. It was impossible to fool a six-year-old audience on this point. One of us!

, rather than attempting to organize some guiding thesis that would structure it (a folly beyond my powers). I would be satisfied with just managing to record a sum of perplexities: those that made me take a special interest in the Terry of my childhood TV, which other celebrities, authors of more resounding fame, could never aspire to. The thing is, Terry was weird. It was impossible to fool a six-year-old audience on this point. One of us!

“Farmer Alfalfa’s Ape Girl”

In the beginning was the Lady. The Terry girls had a special status from the outset, when most of them were still drawn with a nail by Paul himself. Their initial prototype, a streamlined version of the Gibson girls, can be seen in the silent shorts of the Aesop’s Fables period.

The very first Terry Girl (1916).

To tell the truth, they don’t move much (too hard to handle), although these ladies hide an even greater flaw: they are 100% human. In any case, they testify to Terry’s undeniable interest in the female form. One of the few Terry’s animation drafts that have been preserved, Indian Pudding, a Terrytoon from 1930, shows that Terry managed to reserve the animation of the ladies for himself. But the girls of 1930 represent a fundamental advance over those of 1922: they are mice. Dancing mice.

Popcorn, 1931, animator’s breakdown by Devon Baxter. Note that again Paul Terry is in charge of the dancing mouse lady.

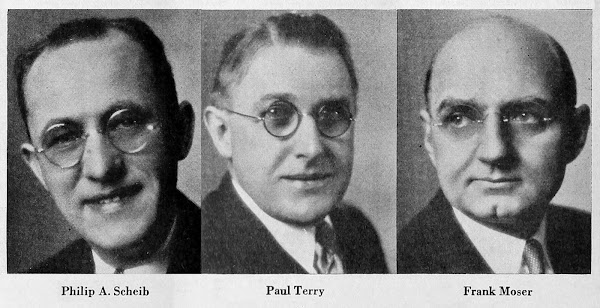

And here lies Terry’s fundamental contribution: his creatures could border on the grotesque, but they were primarily (that is, to the extent that the artist’s technical skills allowed) erotic entities; or they became so as they evolved in successive incarnations provided by artists of the caliber of Frank Moser, Bill Tytla, or Carlo Vinci—different fathers for the same spawn.

Terry’s Cinderella

Let’s compare them for a moment with other animated ladies. Tex Avery’s Red Hot Riding Hood prototype (brilliantly animated by Preston Blair) is a bombshell, but she is specifically designed to fulfill the role of a bombshell, a function made clear by her human physique thrown into a world of animals (wolves, preferably). Blair’s animation is erotic—rather burlesque—but not the character, who is actually a function or an excuse for a series of phallic gags (Avery’s women seem to be divided exclusively between bombshells and mothers-in-law, with the notable exception of some Country Gal). Betty Boop, to mention another human vamp, is also not erotic in herself but rather a caricature of eroticism. Her design has all the signs that designate the thing, but it never becomes the thing itself. Disney, for its part, would have to wait for Freddie Moore to introduce eroticism into its shop (and I’m not referring to the Moore Girls: anything Freddie drew was hot. If anyone could have combined pornography and abstract art, it was him).

But Disney would never go as far as Mr. Terry. For one thing, he would never end a Mickey short like this:

Obviously, it’s difficult to talk about Terry’s beauties without mentioning the artists who animated them, but therein lies my paradoxical argument: if more than one renowned animator, well versed in the history of the genre, confused Bill Tytla’s work with that of Carlo Vinci, it’s because there was a common force behind them. An eccentric mind, camouflaged under the harmless appearance of a Rotary Club member, able to get away with experiments that few would dare to attempt. How about a shot where the camera enters a character’s mouth and then exits through the other side? Something for Ralph Bakshi? Guess again. Submitted for your approval: “Tropical Fish”, 1933.

How about a half-naked woman who rules the jungle mercilessly, exposing her bare buttocks as a royal sign? (As a side line, this short include the exact opposite to the slow burn gag I wrote about some time ago: check out the ape smacking his wife at the beginning. No one can see that one coming!)

\

How about a murderer who, confessing his crimes, first becomes the victim and then the judge who condemns him? A living flashback character, tortured by his memories? Peter Lorre, perhaps? Fritz Lang? Wrong. Dead wrong. “Bluebeard’s Brother”, 1932.

Bill Tytla animated this “flashback monster”, and in the close-up he introduced next, he did everything we will later associate with Jim Tyer… indeed, a strange brotherhood was brewing there. Some of the ideas that were discussed at home bore fruit elsewhere.

Think of Mike Maltese and his early days at Terrytoons, and it’s hard not to associate him with the profusion of Greek wolves or Italian bears… especially some bear family, who, a few years later, avoiding saying too much about their roots, would continue their career in the perfect hands (by then) of Chuck Jones.

Pearl White serials, melodrama, operetta… tons of operetta. Everything comes back again and again in the Terrytoons revolving door, as with those sax-ridden tracks composed by Phil Scheib, suitable for a psychotic nightmare. The continuous use of loops may be an economical measure, but it is also an introduction to trance and the repetitive rhythms of hip hop. And since we are delving into the background of today’s pop culture: Disney’s “Robin Hood” is often cited as the trigger for the furrie furry trend, but I have another idea. Nothing to be too proud of, of course, but it is worth noting. Terry’s girls are still going strong.

Terry’s Dancing Ladies.

But, of course, it’s difficult to define Terry’s girls. Tex’s girls boil down to a single repeated type. Terry, on the other hand, offers variety: there are tall ones and short ones, thin ones and fat ones. Especially fat ones. They are all enticing, in their own strange way. Their appeal lies in their diversity.

This is really a Van Beuren girl from a film by John Foster, who would later continue his career at Terrytoons

Terry’s Thin and Fat

There are also small ones. Very small, in fact. Especially if they are the object of desire of a large predator. A King Kong-like relationship, let’s say, of impossible consummation.

Terry’s Big and Small

This other Terryan device has a long history, and we can trace it back to an Aesop’s Fables from 1922 (“The Fable of the Cat and the Mice”). Over time, it will be refined until it becomes a crystal-clear dynamic that would make the Marquis de Sade blush. In general, the roles are divided between cats and mice (side note: the cat in “The Mad King” is animated with a degree of attention to what a real cat feels that sweeps offstage all the deer on Disney’s payroll). The pinnacle of this twisted logic is, in my opinion, the unsurpassable “Svengali’s Cat” (1946) and its surgical shot of the villain “operating” on his victim. In some poll of dubious legitimacy, “Vertigo” was voted the best film of all time. If that were true, guess which the best cartoon is.

has a long history, and we can trace it back to an Aesop’s Fables from 1922 (“The Fable of the Cat and the Mice”). Over time, it will be refined until it becomes a crystal-clear dynamic that would make the Marquis de Sade blush. In general, the roles are divided between cats and mice (side note: the cat in “The Mad King” is animated with a degree of attention to what a real cat feels that sweeps offstage all the deer on Disney’s payroll). The pinnacle of this twisted logic is, in my opinion, the unsurpassable “Svengali’s Cat” (1946) and its surgical shot of the villain “operating” on his victim. In some poll of dubious legitimacy, “Vertigo” was voted the best film of all time. If that were true, guess which the best cartoon is.

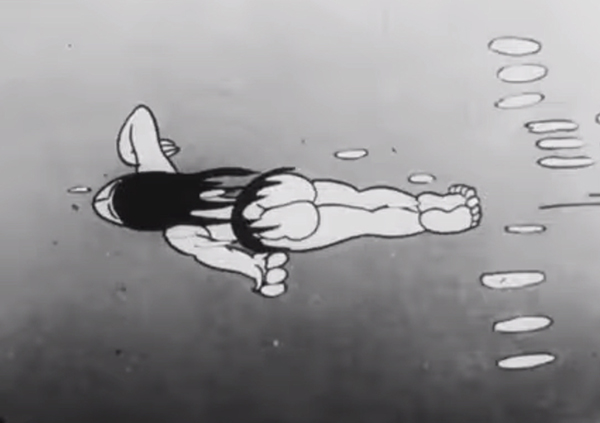

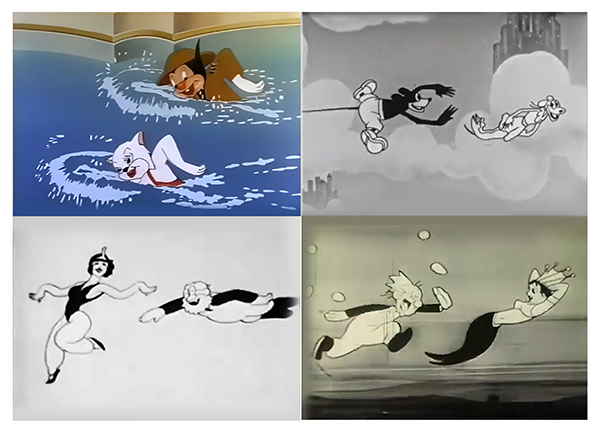

But I was forgetting the dreams. No one seems to have taken the expression “girl of my dreams” more seriously than Terry. Dream is a second nationality for his creatures, and in it, a girl is always lurking, giving rise to pursuits like these:

Swimming in Dreamland.

Life is but a dream, they say. It can also be a nightmare, as we can see in A Midsummer Day Dream, an Aesop’s Fable starring Al Falfa and directed by Harry Bailey in 1929. Terry at its Daliest. But with girls, of course.

But we are barely scratching the surface, icing on the top of the iceberg. We still have many other recurring motifs from Terry’s oeuvre to explore, which can perhaps all be condensed into the figure of the most famous mouse who ever lived on the moon. I will devote my next entry to him – Tomorrow.