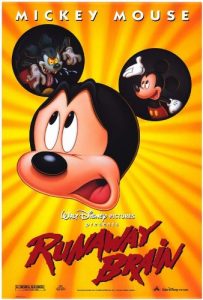

Of all the movie references in a Mickey Mouse cartoon, The Exorcist is probably the most unexpected. And, yet, in 1995’s Runaway Brain, there it is – a scene in the cartoon that replicates an iconic moment from that horror movie masterpiece.

Of all the movie references in a Mickey Mouse cartoon, The Exorcist is probably the most unexpected. And, yet, in 1995’s Runaway Brain, there it is – a scene in the cartoon that replicates an iconic moment from that horror movie masterpiece.

Completely unexpected, yes, and also one of many similar moments in the dark, daring, and hysterical Runaway Brain, which celebrates its 30th anniversary this month.

The short, an homage to classic horror films, finds Mickey Mouse (voiced by Wayne Allwine) short of cash as he looks for a way to take Minnie (Russi Taylor) on a Hawaiian vacation. He finds a way to earn the $999.99 needed when he answers an ad in the newspaper for “mindless work.”

Once there, at “1313 Lobotomy Lane,” he meets a mad scientist (Kelsey Grammer), who, in a classic horror movie trope, has a plan to swap Mickey’s brain with that of the monster Julius (Frank Welker), a large, hulking beast who looks a lot like Pete.

What follows in Runaway Brain is a fast-paced, dizzying ride as the brains are swapped. Julius, with Mickey’s mild-mannered persona, tries to save Minnie from Mickey, who has Julius’ brain, and has been transformed into a version of the iconic Mouse like we’ve never seen him before – fangs, green skin, bloodshot eyes, ragged ears.

The seven minute run time of Runaway Brain is jam-packed with “Easter eggs” and inside jokes – in the opening scene, Mickey plays a “Mortal Kombat”-like video game where Dopey and the Old Hag from Snow White battle each other with martial arts moves, Mickey whistles “Steamboat Bill,” the same song he whistles in Steamboat Willie, as he approaches the scientist’s house, and when photos from his wallet unfurl, revealing a black and white shot of that debut film, Mickey notes, “Oh, that’s old.” Also, the mad scientist’s name, Dr. Frankenollie is a tribute to legendary Disney animators, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, and then, there’s that Exorcist reference, as Mickey approaches Frankenollie’s house in a shot that recreates a memorable moment from The Exorcist, where Father Merrin stands under a streetlight outside of young Regan’s house (featured in the film’s poster).

The seven minute run time of Runaway Brain is jam-packed with “Easter eggs” and inside jokes – in the opening scene, Mickey plays a “Mortal Kombat”-like video game where Dopey and the Old Hag from Snow White battle each other with martial arts moves, Mickey whistles “Steamboat Bill,” the same song he whistles in Steamboat Willie, as he approaches the scientist’s house, and when photos from his wallet unfurl, revealing a black and white shot of that debut film, Mickey notes, “Oh, that’s old.” Also, the mad scientist’s name, Dr. Frankenollie is a tribute to legendary Disney animators, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, and then, there’s that Exorcist reference, as Mickey approaches Frankenollie’s house in a shot that recreates a memorable moment from The Exorcist, where Father Merrin stands under a streetlight outside of young Regan’s house (featured in the film’s poster).

All of this is deftly accomplished thanks to director Chris Bailey, who had worked as an animator for a number of years on such Disney films as The Little Mermaid (1989) and The Lion King (1994) and would go on to serve as animation supervisor for 2011’s Hop at Universal.

Most of Runaway Brain was produced at Disney’s Paris Studio, where a number of talents contributed to the film, including Art Director Ian Gooding, who provided the film with a perfect tone, balancing Disney innocence and horror movie darkness.

Most of Runaway Brain was produced at Disney’s Paris Studio, where a number of talents contributed to the film, including Art Director Ian Gooding, who provided the film with a perfect tone, balancing Disney innocence and horror movie darkness.

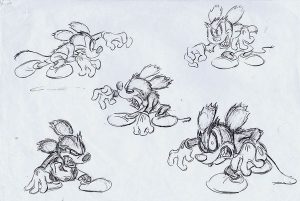

Serving as supervising animator for Mickey was Andreas Deja, one of the Studio’s greatest talents in terms of draftsmanship and personality. He was the perfect choice for Runaway Brain, as he had animated Mickey in 1990s The Prince and the Pauper, and also brought to life several of Disney’s greatest villains: Gaston in Beauty and the Beast (1991), Jafar in Aladdin (1992), and Scar in The Lion King (1994).

In his blog, Deja View Andreas discussed how Runaway Brain came about after story man Tim Hauser had an idea to create a parody of Frankenstein.

The short would be released with Disney’s live-action film A Kid in King Arthur’s Court on August 11, 1995. As the live-action film didn’t ignite the box office, Runaway Brain didn’t fare well either, despite favorable reviews.

The short would be released with Disney’s live-action film A Kid in King Arthur’s Court on August 11, 1995. As the live-action film didn’t ignite the box office, Runaway Brain didn’t fare well either, despite favorable reviews.

It did receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Animated Short Film but lost to Aardman Animations’ Wallace and Gromit film, A Close Shave. Additionally, Runaway Brain was screened out of competition at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival and would receive additional theatrical releases: with the Australian release of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996), the UK release of A Goofy Movie, and with George of the Jungle in 1997.

In 2004, it was released as part of the DVD Walt Disney Treasures: Mickey Mouse in Living Color: Vol. Two, 1939 to Today.

As Runaway Brain was so vastly different from previous Mickey Mouse shorts, it’s been observed that the Disney Studio wasn’t sure how to handle the short in terms of marketing and promotion.

In his 2021 Cartoon Research article discussing the short, Jim Korkis noted:

“Although Runaway Brain received an Oscar nomination and was enjoyed by most of the people who saw it, many Disney Studio executives quietly commented that it was too much like a wacky Warner Brothers cartoon with its raucous action and swift pacing and didn’t like it at all.

Disney Merchandise was even more horrified. They couldn’t create items with Mickey in his huge monster body because it didn’t look like Mickey; it looked like a huge Frankenstein Pete. And if they created merchandise of Mickey’s body when Julius’s brain was in it, then they had this horrific-looking Mickey with sharp teeth and torn ears.”

In the thirty years since its release, these decidedly different aspects of Runaway Brain have allowed a following for the film to grow (there’s even more merchandise now available).

In the thirty years since its release, these decidedly different aspects of Runaway Brain have allowed a following for the film to grow (there’s even more merchandise now available).

What so many have come to appreciate about Runaway Brain is how it deftly balances homage and parody through beautiful animation, with a sly wink that’s never mean-spirited. It also takes chances, following a tradition that Walt Disney himself always wanted for animation.

Andreas summed up Runaway Brain perfectly in another of his blogs, stating: “When the film was released, I wondered about the tempo in which the story was told. It seemed a bit too fast to me. But looking at the short now, it looks perfect. A dynamic, fresh, and entertaining short which echoes Mickey’s early gutsy personality.”