1938 – 1941 would mark a period of considerable change for Lantz and his studio. First, cartoons would begin to bear the credit of “Director”, with early credits primarily divided between Alex Lovy and newcomer Burt Gillett, fresh from a short return to the Disney studios after the closure of operations at Van Beuren.

While Lovy was an internal promotion from the animation ranks, Gillett was retained for his expertise in transitioning to color production, having previously brought Van Beuren studios around to an all-color schedule. Lantz would be the last of the major studios to begin regular releases in 3-strip Technicolor, having abandoned color cartoons for several seasons when the 2-strip Cartune Classics went out of style. (A bit surprising, since Lantz had been the groundbreaker for color animation to begin with, with his sequence from “The King of Jazz” in 1930. However, that situation was more a case of being in the right place at the right time, as Carl Laemmle was willing to shell out the dough to promote the prestige of bandleader Paul Whiteman through the color sequence, but never considered in the early years giving Lantz enough financing to continue such work for the early Oswalds.) Next change would be the color productions themselves, which would begin with 1939’s A-Haunting We Will Go, Gillett’s semi-remake of Disney’s Lonesome Ghosts, with less-expensive animation but wilder and more far-out spooking gags. Within a season, Lantz would drop black-and-white production entirely, in favor of an all-color release line. However, this took its toll, both in budget-stretching and timetables, resulting in substantially fewer cartoons per season than at any time in Lantz’s previous career.

While Lovy was an internal promotion from the animation ranks, Gillett was retained for his expertise in transitioning to color production, having previously brought Van Beuren studios around to an all-color schedule. Lantz would be the last of the major studios to begin regular releases in 3-strip Technicolor, having abandoned color cartoons for several seasons when the 2-strip Cartune Classics went out of style. (A bit surprising, since Lantz had been the groundbreaker for color animation to begin with, with his sequence from “The King of Jazz” in 1930. However, that situation was more a case of being in the right place at the right time, as Carl Laemmle was willing to shell out the dough to promote the prestige of bandleader Paul Whiteman through the color sequence, but never considered in the early years giving Lantz enough financing to continue such work for the early Oswalds.) Next change would be the color productions themselves, which would begin with 1939’s A-Haunting We Will Go, Gillett’s semi-remake of Disney’s Lonesome Ghosts, with less-expensive animation but wilder and more far-out spooking gags. Within a season, Lantz would drop black-and-white production entirely, in favor of an all-color release line. However, this took its toll, both in budget-stretching and timetables, resulting in substantially fewer cartoons per season than at any time in Lantz’s previous career.

The third major change was in characters. Oswald was long gone. Baby Face Mouse would run its course without much of a ripple. Nellie would linger slightly for her last encounters with Ratbone, but also be phased out, from likely lack of sustaining material (though Mighty Mouse and Jay Ward wouldn’t seem to be at a lack for meller-dramatic plots in the distant future). A black character named infamously “L’il Eightball” would have a screen career of only 3 cartoons, though snaring the prestigious spot of starring in the Technicolor “A-Haunting” referenced above, and continuing to have an existence after he had disappeared from the screen in comics pages. Lantz would also dabble in anthology series of one-shots, one being “Nertsery Rhymes” (one of which is discussed below), and another being “Crackpot Cruises”, a trio of shorts attempting to duplicate Tex Avery’s travelogue spoofs from Warner.

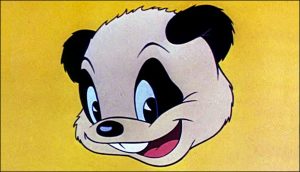

But success would finally shine on Walter, when it was decided to capitalize upon the current event of the debut of a panda at the Bronx Zoo by means of the cartoon, Life Begins For Andy Panda (in which even the characters remark that if Andy is captured and brought to civilization, he will be put in the newsreels). The film was a major hit, providing Lantz with his first original certified star since “Dinky Doodles”. But lightning seemed to strike twice, as within a few films into the series, a supporting character would capture the attention of the public and utterly outshine the new star, much as Daffy Duck had leaped to fame out of a chance appearance in a Porky Pig cartoon – and with a similar insane dementia and utter disregard for the sensibilities of anyone but himself. A redhead with a landmark signature laugh of “Ha ha ha HAAA ha!” We won’t name names – but merely pose the question with which the character would open every episode of his series: “Guess who?”

But success would finally shine on Walter, when it was decided to capitalize upon the current event of the debut of a panda at the Bronx Zoo by means of the cartoon, Life Begins For Andy Panda (in which even the characters remark that if Andy is captured and brought to civilization, he will be put in the newsreels). The film was a major hit, providing Lantz with his first original certified star since “Dinky Doodles”. But lightning seemed to strike twice, as within a few films into the series, a supporting character would capture the attention of the public and utterly outshine the new star, much as Daffy Duck had leaped to fame out of a chance appearance in a Porky Pig cartoon – and with a similar insane dementia and utter disregard for the sensibilities of anyone but himself. A redhead with a landmark signature laugh of “Ha ha ha HAAA ha!” We won’t name names – but merely pose the question with which the character would open every episode of his series: “Guess who?”

The Sailor Mouse – (11/7/38) – Alex Lovy’s creation of Baby Face Mouse predates Chuck Jones’s Sniffles, but seems markedly similar. Oddly, Lovy here sets up a script which might be compared to the earlier Warner Brothers cartoon, I Wanna Be a Sailor. BFM runs away from home, and takes a ride on the bus to the docks. He winds up in the kind of dive sailors go to to get Shanghaied. The experienced tars decide he can’t be a sailor until he passes a test to receive his “union card” – a piece of cheese from the cat’s table. He gets away with a thin slice of Swiss, after dodging thrown cleavers and bullets from the other sailors. BFM winds up rushing home, tearing up the goodbye note he had left for mother, and turning over a sign over his bed, indicating there’s no place like home. Song: “The Old South Seas”, an original shanty sung by the sailor mice at their waterfront dive, presumably written by musical director Frank Marsales.

I’m Just a Jitterbug (1/23/39) – One etymology of the term “jitterbug” is said to have arisen from Cab Calloway’s orchestra. The story is that one of his trombone players called everybody a “bug”, and his favorite booze “jitter”, and was quoted as saying, “Who’s got my jitter, bug?” At least, that’s one story. The jitterbug in this film, who sounds like he’s imitating Bill “Bojangles” Robinson without the tap dancing, leads a smooth and swinging performance of the title song, much to the annoyance of a cuckoo in a clock, who’d like to get some sleep between hours. The cuckoo winds up machine-gunning the entire cast – then he’s able to get some sleep. Song: “I’m Just a Jitterbug” presumably written by Frank Marsales, with an assist on lyrics by Bob Lowry.

Snuffy Skunk’s Party (8/7/39) – Snuffy Skunk, who suffers from the same malady that affects almost all cartoon skunks (represented on soundtrack by a wolf whistle), is throwing himself a birthday party. The other animals of the forest are all incredulous, and wondering what kind of a party he’s going to draw. Meanwhile, Snuffy is expecting a really good time. The party is going along reasonably well as a solo act, but the community dam is about to go under, unleashing a flood on the community. Snuffy becomes the unsung hero of the day, with the flood waters stopping just short of Snuffy’s house from the aroma (almost predicting Mighty Mouse’s power over the Johnstown Flood). Song: “Happy Birthday”, not the traditional song we all know and love, but an original, probably written by Frank Marsales.

The Sleeping Princess (12/4/39) – Your basic Sleeping Beauty scenario, with four fairies who have all seen better days. They represent beauty, wisdom, wealth, and destiny. Destiny plays the Maleficent role, issuing the curse on the princess for being not invited to the ball. However, in this version, Destiny’s invitation is found years after the curse takes effect, misplaced under a rug. Now Destiny, realizing she over-reacted, has to make things right, by enchanting the nearest prince, a real doofus of a guy, to drop whatever he’s doing and come to the palace to wake the princess up. A transformation spell turns the bashful bumbler into perhaps the most awkwardly-animated “realistic” prince ever, and while his kiss awakens the princess, her kiss in response sweeps him off his feet. Songs: You might call it, “A Fairy’s Song”, an expository number scattered throughout the cartoon when story details are necessary.

Andy Panda Goes Fishing (1/22/40) – Andy Panda, as mentioned above, had an immediate impact that had not been seen with either Meany, Miny and Moe or Baby Face Mouse. The early Andy Panda cartoons are all set in the African jungle (never mind that pandas don’t come from Africa). The title pretty much gives you the entire plot, as Andy goes fishing, meets up with some of his jungle friends, and is also introduced to an electric eel. (This particular jungle is a real international community, as the electric eel is generally associated with the waters off the coast of Brazil.) Andy seems to do well at fishing, much to the surprise of Mr. Whippletree the turtle. But the pigmy panda hunters as usual interfere, again lending to the political incorrectness of these early cartoons. Andy sics the electric eel on them, and they all run off, trying to avoid a shocking experience (several of them lighting up like neon signs). Song: An Andy Panda theme song, different than the ones heard instrumentally during the 40’s, and here presented for the only time with a full lyric, underscoring the credits. The theme would subsequently appear instrumentally, including in “Crazy House”.

Kittens’ Mittens (2/12/40) – Based on the well-known nursery rhyme about the kittens who lost their mittens and got no pie. However, the tale receives a modern twist. The subject kittens are stuck-up and too proud to play with orphans, priding themselves on their nice new mittens. When the mittens are accidentally lost from a fall in the brook, they devise a scheme to avoid blame and hopefully still get their pie – by telling Mama a cock-and-bull story about being robbed. Mama buys it – but reacts unexpectedly, taking the kittens immediately to the police station, and raising a fuss of seeking an overhaul of the police department if the criminal isn’t caught. All the usual suspects are rounded up from the usual locations in a police dragnet, and the kittens are asked to choose the guilty party from a line-up. Not knowing upon whom to pin the blame, the kittens choose the orphan, knowing he has no friends. A classic example of police brutality follows as the suspect is given the third degree by the police – however, it is not really as it seems, with all the kittens are seeing being misleading shadows on the office window. Afraid that their lie will result in the suspect’s hanging, the kittens break down and confess their fib. The film ends with all getting pie for telling the truth – even the orphan, who is adopted into the family to make amends. Song: “Three Little Kittens”, not with any melody or lyric normally associated with the nursery rhyme, but an original composition, sung by the Rhythmettes.

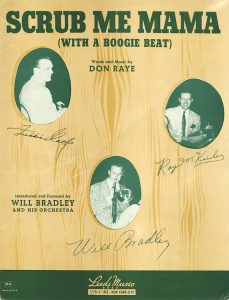

Scrub Me, Mama, With a Boogie Beat (3/28/41) – One of the longest titles assigned to any Lantz cartoon, which likely would have been cut down to something like “The Boogie Washerwoman” if Lantz had had his druthers, but necessarily retained the original title of the musical work from which it derived, being the first in what would become a new direction for Lantz cartoons, building entire episodes musically upon popular rhythm numbers of the day. Carl Stalling had of course inaugurated the concept of building cartoons around musical compositions, but conceived the idea from a classical vein in the creation of Disney’s “Silly Symphony” series. Now that the Silly Symphonies were retired from Disney’s release schedule, Lantz apparently felt the field was open for coining a similar name, and within a few releases, these new musical cartoons would bear the title “Swing Symphony”. Surprisingly, they proved to be more than a passing novelty, and maintained a spot through the mid-1940’s as a highlight of Lantz’s catalog. Much of this was probably due to the inspired performances and scores of Darryl Calker, who had considerable experience in big band settings and could deliver a solid and driving rhythm. Lantz would not stop there, however, and as the series became more firmly established, would not settle merely for the able studio sidemen that Calker could round up for jazz licks and solos, but would also hire genuine names in the jazz world, recapturing some of the excitement Max Fleischer had introduced during the early 1930’s by building cartoons around guest artists such as Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, and Don Redman. We’ll meet several of Lantz’s special guests in subsequent discussions within this article series.

Scrub Me, Mama, With a Boogie Beat (3/28/41) – One of the longest titles assigned to any Lantz cartoon, which likely would have been cut down to something like “The Boogie Washerwoman” if Lantz had had his druthers, but necessarily retained the original title of the musical work from which it derived, being the first in what would become a new direction for Lantz cartoons, building entire episodes musically upon popular rhythm numbers of the day. Carl Stalling had of course inaugurated the concept of building cartoons around musical compositions, but conceived the idea from a classical vein in the creation of Disney’s “Silly Symphony” series. Now that the Silly Symphonies were retired from Disney’s release schedule, Lantz apparently felt the field was open for coining a similar name, and within a few releases, these new musical cartoons would bear the title “Swing Symphony”. Surprisingly, they proved to be more than a passing novelty, and maintained a spot through the mid-1940’s as a highlight of Lantz’s catalog. Much of this was probably due to the inspired performances and scores of Darryl Calker, who had considerable experience in big band settings and could deliver a solid and driving rhythm. Lantz would not stop there, however, and as the series became more firmly established, would not settle merely for the able studio sidemen that Calker could round up for jazz licks and solos, but would also hire genuine names in the jazz world, recapturing some of the excitement Max Fleischer had introduced during the early 1930’s by building cartoons around guest artists such as Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, and Don Redman. We’ll meet several of Lantz’s special guests in subsequent discussions within this article series.

The cartoon itself has been recently discussed in at least one other post on this website, and still ranks as a pure product of its times, quite racially insensitive in its stereotypes, yet essentially avoiding the usual oversized lips and drawling slowness of the other inhabitants of “Lazy Town” when it comes to the visitor who steams into the town dock aboard a riverboat and shakes things up hereabouts – a pale-skinned negress from Harlem with a classy chassis, obviously intended to resemble MGM’s popular Lena Horne, who also seemed to garner public favor in part from being of light complexion. (Such was the then-prevailing pattern of thinking among Hollywood musical producers, likely accounting for why Lena was able to obtain at least guest spots in featured numbers for many MGM musicals, including in Technicolor, while the likes of Ethel Waters would only receive star billing in the all-black cast of “Cabin In the Sky”, and Billie Holiday would only receive one supporting role in “New Orleans” for United Artists.) All the visitor has to do is show a local washerwoman how to scrub her wash in boogie rhythm as they do in Harlem, and the whole town awakens from its half-slumber and parades its stuff down the main street, to bid her a fond farewell as the ship departs. Wonder why they didn’t have the town mayor hang a new sign on the boat landing, officially changing the name from “Lazy Town” to “Boogieville”?

A Universal Studios special disc exists in multiple copies in collectors’ hands with the entire musical track of the film divided on two sides, without spoken dialog or sound effects. It is unknown if this disc was only available to studio employees or made available for purchase at select theaters. The song, however, had its own life on the commercial market predating the film, and was a minor hit with primary sales split between the Ray Bradley/Will McKinley orchestra on Columbia and the Andrews Sisters on Decca. Charlie Barnet issued a Bluebird version with vocal by Ford Leary, but doesn’t get the rhythm right, playing it more like something in strict tempo. A band usually known for essentially strict tempo (Gray Gordon, originally known for his “tic toc rhythm”), did not commercially record the piece, but performed it on film for a Soundie, during a period when he was attempting to modernize his sound – and captures an amazing amount of the spirit of the Darryl Calker performance, in a short which is a refreshing change from the offputting visuals of the Lantz work. A barely recognizable version, played at approximately the tempo of chilled molasses, was recorded by an anonymous organist on the “Skatin’ Toons” label for use in ice and roller rinks.

Woody Woodpecker (7/7/41) – Woody’s debut in Knock Knock was released as an Andy Panda cartoon, and so the bird would have to wait until this, his second appearance, to receive his name, launching his solo starring career that would prove to be Lantz’s enduring meal ticket for the next thirty-odd years. The plot to this one is slight, with Woody’s woodland neighbors convinced that he has a screw loose somewhere, and needs to have his head examined. Woody is tricked into showing off his wood-pecking skills upon a concrete statue, and the impact makes even him start hearing voices suggesting he needs the services of a head-shrinker. He thus visits the local office of Dr. Horace N. Buggy (“Greetings, Gate, let’s operate!”), a fox physician who for no apparent reason seems as daffy as Woody is. The two face off in displays of their insanity for about three minutes, until Woody is thrown out of the screen into a seat in the front row of the theater where the cartoon is running, while the doctor goes into delirious fits on the screen. Woody confides to the theater patrons seated on either side of him that he thinks the doctor is not nearly as funny as the woodpecker, and remarks, “I like cartoons. Don’t you like cartoons?” The patrons respond by trapping Woody up in the folding theater seat. Song: an original number which would be used in several of Woody’s early films as a sort of theme song – “Everybody Thinks I’m Crazy (Knock on Wood)”. Originally performed by Mel Blanc, the song would oddly experience a late revival in 1954’s “Hot Rod Huckster”, then recreated by Woody’s current voice, Grace Stafford.

NEXT: More ‘40’s swing.