The TV era seemed to follow closely on the heels of theatrical output during the 60’s, following many of the same fads and new trends discussed last week – but managed to add an occasional angle of its own not fully dealt with in the theatrical venues. Whole new batches of characters created for the small screen would be placed in awkward moments, while a few old favorites would jump ship to home viewing, in essence “getting with the times” by adapting to the newly-widespread medium which was just becoming affordable enough to establish a presence in most homes, while continuing to be quite the attraction and technological marvel, bringing whole families together around the set to watch prime-time lineups, much as the likes of “Amos ‘n’ Andy” had done a few decades ago for the medium of radio.

It is probably a good jumping-off place for the subject of adaptation to TV to revisit a few late theatrical subjects, which found humor in lampooning the industry. Tex Avery was among the first to frequently joke about it. Drag-a-Long Droopy (MGM, 2/20/54) found Avery’s wolf chasing sheepherder Droopy to keep him from grazing his sheep on the lands of the cattle barons in the old West of Texas. Droopy runs into a saloon, and the wolf calls to the cowpokes inside, “He’s a sheepherder! Shoot ‘im down!” Gunfire is immediately heard inside, and the wolf ducks for cover, anticipating the massacre that must be going on inside. But the gunfire seems to continue for too long, and no one is emerging from the saloon, which visibly appears quiet. The wolf braves a look inside, over the swinging doors. There is no sign of Droopy within, and the saloon interior seems to be half-empty. All that can be seen is a small cluster of cowboys and the bartender, gathered around a television screen located behind the bar, displaying a broadcast of an old black-and-white Western with the volume turned up loud to magnify the continuing gunfire. All the wolf can do is mutter to himself, “Dad gum television!”

It is probably a good jumping-off place for the subject of adaptation to TV to revisit a few late theatrical subjects, which found humor in lampooning the industry. Tex Avery was among the first to frequently joke about it. Drag-a-Long Droopy (MGM, 2/20/54) found Avery’s wolf chasing sheepherder Droopy to keep him from grazing his sheep on the lands of the cattle barons in the old West of Texas. Droopy runs into a saloon, and the wolf calls to the cowpokes inside, “He’s a sheepherder! Shoot ‘im down!” Gunfire is immediately heard inside, and the wolf ducks for cover, anticipating the massacre that must be going on inside. But the gunfire seems to continue for too long, and no one is emerging from the saloon, which visibly appears quiet. The wolf braves a look inside, over the swinging doors. There is no sign of Droopy within, and the saloon interior seems to be half-empty. All that can be seen is a small cluster of cowboys and the bartender, gathered around a television screen located behind the bar, displaying a broadcast of an old black-and-white Western with the volume turned up loud to magnify the continuing gunfire. All the wolf can do is mutter to himself, “Dad gum television!”

• DRAG-A-LONG DROOPY is on Facebook.

“The Three Little Pups”

The Three Little Pups has Avery’s Southern wolf (to seen again in “Blackboard Jumble”) accidentally swallowing a TV set through a straw, then tuning in another old Western, lit up through his belly. The wolf tunes out by twisting his belly button, complaining that “I seen that one last night.” At the end of the film, he makes the ultimate adaptation to the medium, stating to the audience as to his final scheme to blow Droopy and his brothers up with dynamite, “If this don’t work, why…I’ll go into television.” The blast blows apart about a full city block, but misses Droopy’s house entirely, leaving it standing fast in the center of a crater canyon. Inside, Droopy witnesses a new and unusual sight on his TV screen. A wonderfully executed shot appears in black and white, featuring a live-action horse passing in a tracking shot at varying distances from the camera, with an animated overlay of the wolf in fill cowboy outfit, riding tall in the saddle, and shouting “Howdy, you all”, then galloping off into the distance for the fade out. The effect rivals anything in “Roger Rabbit” for the smoothness of animation and seamless mesh of the live-action and animated worlds.

Walter Lantz too would have his fun with TV. Woody Woodpecker’s Jittery Jester (Universal, 11/3/58 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) finds Woody in a medieval period piece, vying for the job of court jester against his frequent arch-rival, Dapper Denver Dooley. While no television is visually depicted, the film wraps up with Dooley captive, and Woody entertaining the king by tossing pies in Dooley’s face. Woody remarks, “This gag will be great, when someone invents television.” (Probably intended as a dig at the current popularity of Soupy Sales, a manic comedian who made pies in the face one of his trademarks.)

Walter Lantz too would have his fun with TV. Woody Woodpecker’s Jittery Jester (Universal, 11/3/58 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) finds Woody in a medieval period piece, vying for the job of court jester against his frequent arch-rival, Dapper Denver Dooley. While no television is visually depicted, the film wraps up with Dooley captive, and Woody entertaining the king by tossing pies in Dooley’s face. Woody remarks, “This gag will be great, when someone invents television.” (Probably intended as a dig at the current popularity of Soupy Sales, a manic comedian who made pies in the face one of his trademarks.)

Little Televillain (Lantz/Universal, Chilly Willy,12/8/58 – Alex Lovy, dir.) follows on the same general track, beginning with Smedly the St. Bernard on a bare set in a TV studio. With a melancholy expression on his face, he addresses the viewing audience. “Y’know, folks, some men become great inventors, business typhoons, or brilliant scientists. And me…” Smedly’s speech is interrupted by a purple splat of something tossed directly at him. “…I get hit in the face with pies.” Smedly takes us into a flashback to explain “how this revoltin’ situation got started.” Mr. Stoop of Stoopendous Television has to find a new show for Saturday night, and must read through a mountain of scripts to do it. He orders Smedly to see he’s nor disturbed, or he will be “pink slipped”.

Who should arrive at the stage door but Chilly Willy, determined to get inside to audition for Mr. Stoop as new talent. Chilly starts to blow a few hot licks on a trumpet, but is seized and silenced by Smedly, who takes him outside, stuffs him inside the bell of his own trumpet, and blows him away. In no more time than it takes for Smedly to turn around, Chilly is back, re-entering the stage door, and slamming it in Smedly’s face, locking him outside. (Note the peculiar oversight, as the door, which has just closed a shot ago with the doorknob on left and hinged on the right, suddenly appears for one shot with the hinges on the left and the knob on the right.) Smedly runs into a nearby lumberyard, grabs up a log as a battering ram, and charges the door. Chilly opens it just before the impact. Smedly crashes through a TV camera, a large spotlight, and a TV screen monitor on the wall. Somehow, Smedly is transported by the monitor into the living room of a woman watching her own TV set. Smedly crashing in through the TV tube. “Pardon the intrusion”, apologizes Smedly, and jumps back into the screen.

Who should arrive at the stage door but Chilly Willy, determined to get inside to audition for Mr. Stoop as new talent. Chilly starts to blow a few hot licks on a trumpet, but is seized and silenced by Smedly, who takes him outside, stuffs him inside the bell of his own trumpet, and blows him away. In no more time than it takes for Smedly to turn around, Chilly is back, re-entering the stage door, and slamming it in Smedly’s face, locking him outside. (Note the peculiar oversight, as the door, which has just closed a shot ago with the doorknob on left and hinged on the right, suddenly appears for one shot with the hinges on the left and the knob on the right.) Smedly runs into a nearby lumberyard, grabs up a log as a battering ram, and charges the door. Chilly opens it just before the impact. Smedly crashes through a TV camera, a large spotlight, and a TV screen monitor on the wall. Somehow, Smedly is transported by the monitor into the living room of a woman watching her own TV set. Smedly crashing in through the TV tube. “Pardon the intrusion”, apologizes Smedly, and jumps back into the screen.

Chilly has set up an assortment of drums in Mr. Stoop’s office, and is about to his the largest one with a huge wooden mallet. Smedly drags Chilly outside again, only to be hit by the mallet, and crack into a hundred pieces as if a shattered piece of pottery. Chilly neatly disposes of the mess with a dustpan and broom, depositing Smedly’s bits into a trash can. Reassembling himself, Smedly pursues Chilly back into the studio, but loses track of him. As Smedly peers out from behind a curtain onto a vacant stage, Chilly takes up a position in the seat of a large TV camera. He begins to play with the buttons of the camera for producing special effects. A “split-screen” button dissects the black and white image of Smedly in the camera lens down the middle, then crosswise, into equal halves – but it appears the real-life Smedly is somehow feeling the painful effects of the process. A “distortion lens” inflates and deflates parts of Smedly’s anatomy like a balloon, then warps his whole body as if made of rubber. In another continuity inconsistency, a third button appears which not visible in the backgrounds of the long shots, appropriately labeled “close-up”. The in-lens vision of Smedly is immediately brought to a point as if his nose were almost touching the camera – and it appears the real-life Smedly has been drawn there too, visibly snarling! Chilly beats a retreat, and Smedly attempts to follow his progress on a bank of TV monitors. Chilly appears on one screen with his image flipping with an unstable vertical hold. Smedly’s eyeballs exhibit the same flipping pattern vertically. Chilly runs through various sets, collapsing a used car in a commercial, jostling the hand of a woman pitching a brand of make-up so that she draws a moustache upon her face, and appearing under an old cowboy’s Stetson hat. Smedly finally gives chase again, catching up with Chilly on the set of a refrigerator commercial. Both characters race inside the refrigerator, and the door closes. As a saleslady attempts to show off the refrigerator interior on camera, Chilly emerges, used to the cold, but Smedly appears in solid blue, caught in the refrigerator’s instant “deep freeze”. The scene dissolves to Mr. Stoop’s office, where he has taken a break from script-reading to watch the day’s broadcasts on his own set. He is rolling with laughter at what he has seen, and declares he has found his new show. The scene returns to the present, for the premiere of the “I Love Smedly” show (a title lampooning the perennial “I Love Lucy”). The curtain opens to find Chilly, armed with a tall stack of pies, and pitching them one-by-one and the motionless Smedly. Between layers of purple goop upon his face, Smedly closes with the remark. “There’s no business like show business.”

Chilly has set up an assortment of drums in Mr. Stoop’s office, and is about to his the largest one with a huge wooden mallet. Smedly drags Chilly outside again, only to be hit by the mallet, and crack into a hundred pieces as if a shattered piece of pottery. Chilly neatly disposes of the mess with a dustpan and broom, depositing Smedly’s bits into a trash can. Reassembling himself, Smedly pursues Chilly back into the studio, but loses track of him. As Smedly peers out from behind a curtain onto a vacant stage, Chilly takes up a position in the seat of a large TV camera. He begins to play with the buttons of the camera for producing special effects. A “split-screen” button dissects the black and white image of Smedly in the camera lens down the middle, then crosswise, into equal halves – but it appears the real-life Smedly is somehow feeling the painful effects of the process. A “distortion lens” inflates and deflates parts of Smedly’s anatomy like a balloon, then warps his whole body as if made of rubber. In another continuity inconsistency, a third button appears which not visible in the backgrounds of the long shots, appropriately labeled “close-up”. The in-lens vision of Smedly is immediately brought to a point as if his nose were almost touching the camera – and it appears the real-life Smedly has been drawn there too, visibly snarling! Chilly beats a retreat, and Smedly attempts to follow his progress on a bank of TV monitors. Chilly appears on one screen with his image flipping with an unstable vertical hold. Smedly’s eyeballs exhibit the same flipping pattern vertically. Chilly runs through various sets, collapsing a used car in a commercial, jostling the hand of a woman pitching a brand of make-up so that she draws a moustache upon her face, and appearing under an old cowboy’s Stetson hat. Smedly finally gives chase again, catching up with Chilly on the set of a refrigerator commercial. Both characters race inside the refrigerator, and the door closes. As a saleslady attempts to show off the refrigerator interior on camera, Chilly emerges, used to the cold, but Smedly appears in solid blue, caught in the refrigerator’s instant “deep freeze”. The scene dissolves to Mr. Stoop’s office, where he has taken a break from script-reading to watch the day’s broadcasts on his own set. He is rolling with laughter at what he has seen, and declares he has found his new show. The scene returns to the present, for the premiere of the “I Love Smedly” show (a title lampooning the perennial “I Love Lucy”). The curtain opens to find Chilly, armed with a tall stack of pies, and pitching them one-by-one and the motionless Smedly. Between layers of purple goop upon his face, Smedly closes with the remark. “There’s no business like show business.”

• “Little Televillain” is on the Internet Archive

Ballyhooey (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 1/2/60 – Alex Lovy, dir.) finds Woody sitting before a set in his living room, trying to adapt to the experience of watching his favorite TV game show, “Win the Whole Wide World”. The only problem is, it’s quite difficult to concentrate on any game, when the entire proceedings is prefaced by an endless run of commercials, from the show’s sponsor, alternate sponsor, and alternate-alternate sponsor. Woody is burning up with frustration, and is finally forced to stifle the endless jabber by wearing a pair of earmuffs, and falls asleep. The announcer ultimately has to scream for everyone to “wake up” when it is finally time to reveal the prize question: “Who is buried in Grant’s tomb?” Woody is sure he has the answer, writes it on a piece of paper, and races to the TV station to be the first one to provide it. He wrestles with an over-zealous usher who believes no one should be permitted entrance to the show in progress, accidentally punctures with his beak a “puncture-proof” tire advertised by the Goodgrief Rubber Company, but finally makes it to the show. He hands his written answer to the show’s host, who reads it out loud with surprise and confusion: “Napoleon?” The host consults with two old professors with beards who act as research consultants, and the conclusion is reached that the answer is wrong. The correct answer is – George Washington. But Woody wins a consolation prize – a trip South for the winter, all expenses paid. It is not as Woody expected. Woody spends the winter shivering in an igloo at the South Pole, with only a portable TV set inside for entertainment. The game show, “Hi-Ho Eskimo” begins on the screen – but launches into its own series of “words from our sponsors”. “Oh, no”, says Woody, pulling out a pistol, and shooting three holes in the TV screen. The host falls and disappears out of the picture frame. Then the screen image is replaced by a card, reading, “Due to difficulties beyond our control, the picture has been interrupted.”

Ballyhooey (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 1/2/60 – Alex Lovy, dir.) finds Woody sitting before a set in his living room, trying to adapt to the experience of watching his favorite TV game show, “Win the Whole Wide World”. The only problem is, it’s quite difficult to concentrate on any game, when the entire proceedings is prefaced by an endless run of commercials, from the show’s sponsor, alternate sponsor, and alternate-alternate sponsor. Woody is burning up with frustration, and is finally forced to stifle the endless jabber by wearing a pair of earmuffs, and falls asleep. The announcer ultimately has to scream for everyone to “wake up” when it is finally time to reveal the prize question: “Who is buried in Grant’s tomb?” Woody is sure he has the answer, writes it on a piece of paper, and races to the TV station to be the first one to provide it. He wrestles with an over-zealous usher who believes no one should be permitted entrance to the show in progress, accidentally punctures with his beak a “puncture-proof” tire advertised by the Goodgrief Rubber Company, but finally makes it to the show. He hands his written answer to the show’s host, who reads it out loud with surprise and confusion: “Napoleon?” The host consults with two old professors with beards who act as research consultants, and the conclusion is reached that the answer is wrong. The correct answer is – George Washington. But Woody wins a consolation prize – a trip South for the winter, all expenses paid. It is not as Woody expected. Woody spends the winter shivering in an igloo at the South Pole, with only a portable TV set inside for entertainment. The game show, “Hi-Ho Eskimo” begins on the screen – but launches into its own series of “words from our sponsors”. “Oh, no”, says Woody, pulling out a pistol, and shooting three holes in the TV screen. The host falls and disappears out of the picture frame. Then the screen image is replaced by a card, reading, “Due to difficulties beyond our control, the picture has been interrupted.”

• “Ballyhooey” is on the Internet Archive

Terrytoons would also present its own take on adapting to the small screen world in Dinky duck’s final film, It’s A Living (Terrytoons/Fox, 2/57 – Win Hoskins, dir.). Dinky becomes fed up with endlessly being chased on the theatrical screen by every kind of predator imaginable, including current pursuit by an alligator, and orders the projectionist to stop the cartoon right in the middle of a screening, so that he can exit the screen and walk out of the theater, quitting cartoons. Dinky wanders into the big city, and stops outside the window of a TV store. A screen pops on inside the window, where a cat sings in a high-pitched yowl about the merits of a comfy mattress he is resting upon. Dinky is enlightened by the advertisement – not about the product, but by the performer. “Boy what a soft job. I can do that. I got a squeaky voice, too!” Dinky races to the Go Go TV studios, determined to get a job on television.

Terrytoons would also present its own take on adapting to the small screen world in Dinky duck’s final film, It’s A Living (Terrytoons/Fox, 2/57 – Win Hoskins, dir.). Dinky becomes fed up with endlessly being chased on the theatrical screen by every kind of predator imaginable, including current pursuit by an alligator, and orders the projectionist to stop the cartoon right in the middle of a screening, so that he can exit the screen and walk out of the theater, quitting cartoons. Dinky wanders into the big city, and stops outside the window of a TV store. A screen pops on inside the window, where a cat sings in a high-pitched yowl about the merits of a comfy mattress he is resting upon. Dinky is enlightened by the advertisement – not about the product, but by the performer. “Boy what a soft job. I can do that. I got a squeaky voice, too!” Dinky races to the Go Go TV studios, determined to get a job on television.

Dinky boards a crowded elevator in the executive tower of the studio, and s compressed by the elevator’s speed as it zooms to the top. He pops back to shape, finding himself in an audition/waiting room, along with four other human would-be applicants. The humans all snub Dinky when the duck looks their way. The door of an inner office opens, and a small bespectacled talent scout peruses the group in wait for him. The four humans immediately break into their own respective random song and dance, including a rocker, an operatic soprano, a cowboy, and a fourth of indeterminate talents. The scout ignores them all, but, spotting Dinky nearly being trodden upon below their feet, remarks, “Now here’s a fresh personality.” The background fades away, and morphs to a board room table, where the scout shows Dinky off as his “new discovery”. Another background transformation, and Dinky is put through a hurried screen test. The scout urges management to sign Dinky up, and just like that, Dinky is standing on a table, atop a contract five times larger than he is, taking in the fine print. “Whereas, said duck agrees that his entire services,…whether asleep or awake???…” reads the puzzled Dinky. “I knew ya’d like it. Just sign here”, urges the scout, grabbing up Dinky in his hand, dipping his beak into an inkwell, and using it to sign Dinky’s name to the contract like a fountain pen.

Dinky boards a crowded elevator in the executive tower of the studio, and s compressed by the elevator’s speed as it zooms to the top. He pops back to shape, finding himself in an audition/waiting room, along with four other human would-be applicants. The humans all snub Dinky when the duck looks their way. The door of an inner office opens, and a small bespectacled talent scout peruses the group in wait for him. The four humans immediately break into their own respective random song and dance, including a rocker, an operatic soprano, a cowboy, and a fourth of indeterminate talents. The scout ignores them all, but, spotting Dinky nearly being trodden upon below their feet, remarks, “Now here’s a fresh personality.” The background fades away, and morphs to a board room table, where the scout shows Dinky off as his “new discovery”. Another background transformation, and Dinky is put through a hurried screen test. The scout urges management to sign Dinky up, and just like that, Dinky is standing on a table, atop a contract five times larger than he is, taking in the fine print. “Whereas, said duck agrees that his entire services,…whether asleep or awake???…” reads the puzzled Dinky. “I knew ya’d like it. Just sign here”, urges the scout, grabbing up Dinky in his hand, dipping his beak into an inkwell, and using it to sign Dinky’s name to the contract like a fountain pen.

No sooner is Dinky signed, then his tasks begin. He is promptly thrust before a camera, to perform a live advertisement for the water resistance of the Draincoat raincoat. Dinky has one line of dialog: “Like water off a duck’s back.” This slogan is startlingly demonstrated, by dousing Dinky with a high-pressure fire hose, nearly drowning the duck in three feet of water. The water subsides, and pours out of Dinky’s ears like twin fountains. He is promptly grabbed up by another announcer, for a commercial upon the merits of a freezer in retaining the flavor of succulent fowl. Wet Dinky is placed into a freezer compartment, and immediately frozen into an ice cube. Next, he is handed to the salesperson of the Sweat Beam Super Sun Ray, a lamp guaranteed to bring the rays of the beach directly into your home. Its heat melts Dinky out of the ice, but toasts him to a red-hot state over his entire body. The duck is handed to a caricature of John Cameron Swayze, well-known salesman in real life for Timex watches. Here selling Allproof watches, the announcer demonstrates with Dinky that the watch is heat proof (by fastening it around Dinky’s neck while still red hot), shockproof (by bopping Dinky and the watch headfirst against a table top), and waterproof (dunking Dinky in an aquarium tank, while a chorus sings a jingle about the watch running even better when it’s wetter). As drenched Dinky crawls out of the tank, a metallically-reverberating voice repeats over and over in menacing tones “Niripsa, Niripsa, NIRIPSA!” The unseen announcer (voiced by Allen Swift), continues, “You can duck your work, but you can’t duck a headache.” Dinky has no idea what is coming, and in a panic starts to run. But his path is blocked by a human hand holding a large bell, tipped so that Dinky runs right inside it. The bell is dropped over Dinky, then sounded loudly with a hard blow from a hammer. As the bell is raised, we see Dinky inside reverberating, while the announcer talks of “that ringing headache”. The audience is advised to take Niripsa – that’s Aspirin spelled backwards.

No sooner is Dinky signed, then his tasks begin. He is promptly thrust before a camera, to perform a live advertisement for the water resistance of the Draincoat raincoat. Dinky has one line of dialog: “Like water off a duck’s back.” This slogan is startlingly demonstrated, by dousing Dinky with a high-pressure fire hose, nearly drowning the duck in three feet of water. The water subsides, and pours out of Dinky’s ears like twin fountains. He is promptly grabbed up by another announcer, for a commercial upon the merits of a freezer in retaining the flavor of succulent fowl. Wet Dinky is placed into a freezer compartment, and immediately frozen into an ice cube. Next, he is handed to the salesperson of the Sweat Beam Super Sun Ray, a lamp guaranteed to bring the rays of the beach directly into your home. Its heat melts Dinky out of the ice, but toasts him to a red-hot state over his entire body. The duck is handed to a caricature of John Cameron Swayze, well-known salesman in real life for Timex watches. Here selling Allproof watches, the announcer demonstrates with Dinky that the watch is heat proof (by fastening it around Dinky’s neck while still red hot), shockproof (by bopping Dinky and the watch headfirst against a table top), and waterproof (dunking Dinky in an aquarium tank, while a chorus sings a jingle about the watch running even better when it’s wetter). As drenched Dinky crawls out of the tank, a metallically-reverberating voice repeats over and over in menacing tones “Niripsa, Niripsa, NIRIPSA!” The unseen announcer (voiced by Allen Swift), continues, “You can duck your work, but you can’t duck a headache.” Dinky has no idea what is coming, and in a panic starts to run. But his path is blocked by a human hand holding a large bell, tipped so that Dinky runs right inside it. The bell is dropped over Dinky, then sounded loudly with a hard blow from a hammer. As the bell is raised, we see Dinky inside reverberating, while the announcer talks of “that ringing headache”. The audience is advised to take Niripsa – that’s Aspirin spelled backwards.

More voices are heard, calling for Dinky on the next set. But the duck can plainly see this dream life is not what it’s cracked up to be, and decides to flee before he cracks up himself. As spotlights shine down upon his path, Dinky makes haste with his feet. He manages without further repercussions to reach the street, and races back to the movie house, where the frozen image from his cartoon is still lit up upon the screen. “I’m back. I’m back!”, he shouts to the audience, and climbs back into the theater screen. Signaling with a wave to the alligator, Dinky urges him forward, saying, “Let’s go, buddy.” The action picks up right where it left off, with the alligator snapping at Dinky’s heels. Dinky turns to the audience and camera while swimming like mad, remarking in calm tones, “Oh, well. It’s a living.”

The Wildman of Wildsville

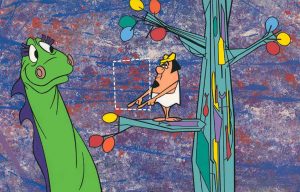

A pursuit begins, with Van Gogh taking to the trees a la Tarzan (painting some of the vines into existence himself). The wild man waits in another tree while Cecil orders him to come down before he counts ten. Van Gogh leaps out of the tree when Cecil has only counted to one, crushing Cecil into the ground below him. Van Gogh looks down at what remains visible of Cecil, and remarks to the camera, “Smashed.” Van Gogh whistles for transportation from a nearby cave, and compresses a live Jaguar into a sports car. He doesn’t get far, crashing it into a tree. Van Gogh sees a circle of “tweeting birds” circling his dizzy head, and remarks, “Like Birdland, Dad”. (Reference to the famous Bebop club where folks like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie reigned.) Van Gogh takes to the vines again, reciting as a beat poem, “Hey Diddle Diddle, the cat and the fiddle, the cow jumped over the moon…Dig that crazy milk shake!”“ He misses his hold on the next vine, and falls, causing his Tarzan leotard to snag on a branch and rip off, while Van Gogh falls in the buff, using his hands to cover his unmentionables. “Cool, man, cool!” he remarks at his nudity. Cecil provides a special delivery of a new outfit for him, consisting of a straight jacket. When Cecil tries to install a belt in the back, the battle rages in swirling spirals on camera, and when the dust clears, Cecil is himself wrapped up tight in the jacket, with its oversized sleeves extending out above his head, giving the appearance of rabbit ears.

A pursuit begins, with Van Gogh taking to the trees a la Tarzan (painting some of the vines into existence himself). The wild man waits in another tree while Cecil orders him to come down before he counts ten. Van Gogh leaps out of the tree when Cecil has only counted to one, crushing Cecil into the ground below him. Van Gogh looks down at what remains visible of Cecil, and remarks to the camera, “Smashed.” Van Gogh whistles for transportation from a nearby cave, and compresses a live Jaguar into a sports car. He doesn’t get far, crashing it into a tree. Van Gogh sees a circle of “tweeting birds” circling his dizzy head, and remarks, “Like Birdland, Dad”. (Reference to the famous Bebop club where folks like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie reigned.) Van Gogh takes to the vines again, reciting as a beat poem, “Hey Diddle Diddle, the cat and the fiddle, the cow jumped over the moon…Dig that crazy milk shake!”“ He misses his hold on the next vine, and falls, causing his Tarzan leotard to snag on a branch and rip off, while Van Gogh falls in the buff, using his hands to cover his unmentionables. “Cool, man, cool!” he remarks at his nudity. Cecil provides a special delivery of a new outfit for him, consisting of a straight jacket. When Cecil tries to install a belt in the back, the battle rages in swirling spirals on camera, and when the dust clears, Cecil is himself wrapped up tight in the jacket, with its oversized sleeves extending out above his head, giving the appearance of rabbit ears.

Clampett remembers his roots, having Cecil utter the line. “Eh, what’s up pops?” He also gets away with underscore using a few actual bars of “Merrily We Roll Along”. “Don’t Bugs me, man, don’t Bugs me!”, quips the Wildman, painting a giant carrot and stuffing it in Cecil’s mouth. The final sequence has Van Gogh painting an entire coffee house for himself with a paint roller, then the outlines of musical instruments to provide cool music. Beany, Captain, and Crowy finally catch up, and with a few flings of his paintbrush, Van Gogh transforms all of them and Cecil into beatnik outfits, with dark glasses, goatee beards, and berets. “Oh, well, if ya can’t beatnik ‘em, join ‘em”, concludes Cecil. The cast recite in beat “Twinkle twinkle, little beatnik”, at the conclusion of which Crowy remarks, “Endsville.” An iris out begins, not round, but with the walls of the camera frame closing in from all sides. Van Gogh reaches forwards, stopping the closing sides, and steps out through them, stating, “Man, I don’t dig anything that’s square.” Before he can turn around, the sides have succeeded in closing behind him, shutting him on the outside. Van Gogh bops his nose trying to go back through the now solid blackness, and turns again to the camera, his nose throbbing to a bongo beat, for the curtain line: “How far out can you get?”

Clampett remembers his roots, having Cecil utter the line. “Eh, what’s up pops?” He also gets away with underscore using a few actual bars of “Merrily We Roll Along”. “Don’t Bugs me, man, don’t Bugs me!”, quips the Wildman, painting a giant carrot and stuffing it in Cecil’s mouth. The final sequence has Van Gogh painting an entire coffee house for himself with a paint roller, then the outlines of musical instruments to provide cool music. Beany, Captain, and Crowy finally catch up, and with a few flings of his paintbrush, Van Gogh transforms all of them and Cecil into beatnik outfits, with dark glasses, goatee beards, and berets. “Oh, well, if ya can’t beatnik ‘em, join ‘em”, concludes Cecil. The cast recite in beat “Twinkle twinkle, little beatnik”, at the conclusion of which Crowy remarks, “Endsville.” An iris out begins, not round, but with the walls of the camera frame closing in from all sides. Van Gogh reaches forwards, stopping the closing sides, and steps out through them, stating, “Man, I don’t dig anything that’s square.” Before he can turn around, the sides have succeeded in closing behind him, shutting him on the outside. Van Gogh bops his nose trying to go back through the now solid blackness, and turns again to the camera, his nose throbbing to a bongo beat, for the curtain line: “How far out can you get?”

King Features was also prone to satirize the beat generation. Coffee House (Popeye, circa 1960 – Jack Kinney, dir.) was a last memorable instance of Popeye being out of step with Olive’s obsession with current trends. Olive exchanges her blouse and skirt with the stripe for a pant suit, turtle-neck sweater, beret, and round spectacles. Her hair comes down instead of being tied up in a bun. When Popeye rings at the door, she addresses him in beat talk. “Enter my pad. Gimme the hug, big brain.” Popeye appears in shock. “Olive, speak to me. I better call the doctor. Has you had it long?” Not cool. Olive is not only nonplused, but expected someone else – who makes his arrival driving a motor scooter through the door, knocking Popeye down. Bluto (again renamed Brutus for television, but we’ll call him here by his right name) is also decked out in similar garb to Olive, and makes a point of turning his face to Popeye to point out his new invulnerability to Popeye’s fisticuffs, thanks to part of his wardrobe change – “Glasses, Daddy-o”. Bluto and Olive embrace, and begin a string of mutual verbal compliments to each other in classic beat phrases, including “Crazy”, “I dig ya the most”, “You’re the coolest”, “Nutty, frantic”, “The end”, “From outer space, gone.” Popeye’s head looks las if it’s watching a ping pong match, and all he can remark is “What’d ya say? What’d ya say?” Snapping her fingers, Olive responds, “In Squareville we mean, get lost sailor. We’re real gone, but you – go!” Bluto adds, “Yeah, go – like far out”, socking Popeye into a window frame and rolling him up in a windowshade. Bluto then stuffs Popeye into the back of the TV set, emphasizing its “square” picture tube. Popeye tries to block the front door, but Bluto’s scooter runs Popeye over again, and also carries Olive off astride it. Popeye vows he’ll break up that “combo” if it’s the last thing he does.

King Features was also prone to satirize the beat generation. Coffee House (Popeye, circa 1960 – Jack Kinney, dir.) was a last memorable instance of Popeye being out of step with Olive’s obsession with current trends. Olive exchanges her blouse and skirt with the stripe for a pant suit, turtle-neck sweater, beret, and round spectacles. Her hair comes down instead of being tied up in a bun. When Popeye rings at the door, she addresses him in beat talk. “Enter my pad. Gimme the hug, big brain.” Popeye appears in shock. “Olive, speak to me. I better call the doctor. Has you had it long?” Not cool. Olive is not only nonplused, but expected someone else – who makes his arrival driving a motor scooter through the door, knocking Popeye down. Bluto (again renamed Brutus for television, but we’ll call him here by his right name) is also decked out in similar garb to Olive, and makes a point of turning his face to Popeye to point out his new invulnerability to Popeye’s fisticuffs, thanks to part of his wardrobe change – “Glasses, Daddy-o”. Bluto and Olive embrace, and begin a string of mutual verbal compliments to each other in classic beat phrases, including “Crazy”, “I dig ya the most”, “You’re the coolest”, “Nutty, frantic”, “The end”, “From outer space, gone.” Popeye’s head looks las if it’s watching a ping pong match, and all he can remark is “What’d ya say? What’d ya say?” Snapping her fingers, Olive responds, “In Squareville we mean, get lost sailor. We’re real gone, but you – go!” Bluto adds, “Yeah, go – like far out”, socking Popeye into a window frame and rolling him up in a windowshade. Bluto then stuffs Popeye into the back of the TV set, emphasizing its “square” picture tube. Popeye tries to block the front door, but Bluto’s scooter runs Popeye over again, and also carries Olive off astride it. Popeye vows he’ll break up that “combo” if it’s the last thing he does.

We fade in on the local coffee house, with the usual audience of ultra-cool “beats” seated at various tables, some playing flute, bongos, and guitar. Bluto is reciting his newest composition in beat poetry. “Ode to an Onion” to Olive, with couplets Popeye just can’t understand as he slips inside and hides under their table. Bluto sketches his idea of a portrait of Olive on the tablecloth, looking like an eyeball attached to a stick figure in the mode of Picasso. Popeye grabs from his pocket a sketch pad and pencil, and pops out from under the table, presenting Olive with a realistic image of herself in a Victorian dress. Not hip. Popeye begins to realize if you can’t lick ‘em, join ‘em, so tries to get in the musical mood of the place by dancing a sailor’s hornpipe. Bluto picks up Popeye, spreads his arms out like wings, and throws him like a paper airplane across the room, where Popeye crashes into a bass fiddle not currently in use. The sailor declares it’s time to acquire a little culture – and consumes a can labeled, “Cultured Spinach”. Now Popeye can dance the hornpipe, but do it while accompanying himself on guitar in beat rhythms. “Cool, cool” starts an endless chant from the crowd. Bluto charges Popeye. Popeye remains a gentleman, remembering not to sock a man with glasses – but having nothing against letting the man with glasses sock himself. So Popeye dons a painter’s outfit, and at the right moment holds out his fist with upraised thumb to judge painting perspective. Bluto runs right into the clenched fist, administering his own sock to himself. Now Popeye reverts back to his old clothes, but takes up a red cape, treating Bluto like a bull in the arena. Bluto makes several passes, which Popeye nimbly dodges in the manner of an experienced matador. Even Olive by now is swept up in the crowd’s repetitions of “Cool”, and then “Ole”. Bluto makes a final charge, which Popeye declares “El Momento De La Truth”, as he holds out his extended fist again. Bluto hits it head on, delivering to himself the final knockout blow. The film ends with Olive and Popeye walking home together, Olive now directing another string of beat compliments to Popeye as “the utmost, the kookiest, and besides that, you’re hip.” Popeye by now probably only understands about half of it, but gets the general idea, responding with a slight updating of one of his favorite catch-phrases: “Like, I yam what I yam.”

We fade in on the local coffee house, with the usual audience of ultra-cool “beats” seated at various tables, some playing flute, bongos, and guitar. Bluto is reciting his newest composition in beat poetry. “Ode to an Onion” to Olive, with couplets Popeye just can’t understand as he slips inside and hides under their table. Bluto sketches his idea of a portrait of Olive on the tablecloth, looking like an eyeball attached to a stick figure in the mode of Picasso. Popeye grabs from his pocket a sketch pad and pencil, and pops out from under the table, presenting Olive with a realistic image of herself in a Victorian dress. Not hip. Popeye begins to realize if you can’t lick ‘em, join ‘em, so tries to get in the musical mood of the place by dancing a sailor’s hornpipe. Bluto picks up Popeye, spreads his arms out like wings, and throws him like a paper airplane across the room, where Popeye crashes into a bass fiddle not currently in use. The sailor declares it’s time to acquire a little culture – and consumes a can labeled, “Cultured Spinach”. Now Popeye can dance the hornpipe, but do it while accompanying himself on guitar in beat rhythms. “Cool, cool” starts an endless chant from the crowd. Bluto charges Popeye. Popeye remains a gentleman, remembering not to sock a man with glasses – but having nothing against letting the man with glasses sock himself. So Popeye dons a painter’s outfit, and at the right moment holds out his fist with upraised thumb to judge painting perspective. Bluto runs right into the clenched fist, administering his own sock to himself. Now Popeye reverts back to his old clothes, but takes up a red cape, treating Bluto like a bull in the arena. Bluto makes several passes, which Popeye nimbly dodges in the manner of an experienced matador. Even Olive by now is swept up in the crowd’s repetitions of “Cool”, and then “Ole”. Bluto makes a final charge, which Popeye declares “El Momento De La Truth”, as he holds out his extended fist again. Bluto hits it head on, delivering to himself the final knockout blow. The film ends with Olive and Popeye walking home together, Olive now directing another string of beat compliments to Popeye as “the utmost, the kookiest, and besides that, you’re hip.” Popeye by now probably only understands about half of it, but gets the general idea, responding with a slight updating of one of his favorite catch-phrases: “Like, I yam what I yam.”

The Snuffy Smith cartoon series often seemed to focus on Snuffy and Loweezy’s attempts to adapt to the intrusions of modern life into their backwoods rural existence. But perhaps no episode more exemplified the clash of two worlds than Beauty and the Beat (King Features/Paramount, circa 1964 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.). Two beatnik musicians seem to have lost their way, and wander into Hootin Holler, one asking the other, “Hey man, what part of Greenwich Village is this?” Barney Google is in need of help, hanging by his hands from the cabin roof because a ladder has fallen out from under him. Snuffy, snoozing under a tree, and the only one within earshot of Barney’s cries for assistance, asks if help can be given while he remains asleep. Barney responds, “No”, and Snuffy answers, “Then I ain’t helpin’.” Barney falls from the roof, and curses out Snuffy. Opening only one eye, Snuffy reacts to the insults, “Sticks and stones can break my bones, but names’ll never hurt me.” The two beatniks happen at the moment to pass within earshot, and are totally “sent” by Snuffy’s poetic observation, thinking it an original composition of beat poetry. They both appear before Snuffy, bowing to him as if the master of his craft, and implore him to “Go, man, go.” Snuffy stands up, and begins to walk away. When asked by the beatniks what he is doing, Snuffy responds, “Great balls of fire, ya told me to go.” The beatniks translate, requesting more poetry from Snuffy, and begin snapping their fingers rhythmically. Sniffy starts to imitate their snapping beat, and recites in rhythm the first thing that pops into his head: “Hickory Dickory Dock, the mouse ran up the clock…” The small beatnik faints, smiling, and the other beatnik informs Snuffy that “Your verse fractured him.” The beatniks decide a shrine must be built to their new king of beat poetry – and so construct “The Most” coffee house on the hallowed hollow. Before premiering their new poetic find to the world, the beatniks realize a change in Snuffy’s appearance is in order. Those threads have to go – that is, go in the other sense, not as in “go” for more poetry. A sweater, black trousers, and sandals become Snuffy’s new wardrobe. Still, something is missing, thanks to Snuffy’s bald head. More hair, and a beard. Fortunately, it turns out that each of the beatniks is wearing hair that is partially fake – so one provides Snuffy with his wig, while the other loans Snuffy his fake beard.

The Snuffy Smith cartoon series often seemed to focus on Snuffy and Loweezy’s attempts to adapt to the intrusions of modern life into their backwoods rural existence. But perhaps no episode more exemplified the clash of two worlds than Beauty and the Beat (King Features/Paramount, circa 1964 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.). Two beatnik musicians seem to have lost their way, and wander into Hootin Holler, one asking the other, “Hey man, what part of Greenwich Village is this?” Barney Google is in need of help, hanging by his hands from the cabin roof because a ladder has fallen out from under him. Snuffy, snoozing under a tree, and the only one within earshot of Barney’s cries for assistance, asks if help can be given while he remains asleep. Barney responds, “No”, and Snuffy answers, “Then I ain’t helpin’.” Barney falls from the roof, and curses out Snuffy. Opening only one eye, Snuffy reacts to the insults, “Sticks and stones can break my bones, but names’ll never hurt me.” The two beatniks happen at the moment to pass within earshot, and are totally “sent” by Snuffy’s poetic observation, thinking it an original composition of beat poetry. They both appear before Snuffy, bowing to him as if the master of his craft, and implore him to “Go, man, go.” Snuffy stands up, and begins to walk away. When asked by the beatniks what he is doing, Snuffy responds, “Great balls of fire, ya told me to go.” The beatniks translate, requesting more poetry from Snuffy, and begin snapping their fingers rhythmically. Sniffy starts to imitate their snapping beat, and recites in rhythm the first thing that pops into his head: “Hickory Dickory Dock, the mouse ran up the clock…” The small beatnik faints, smiling, and the other beatnik informs Snuffy that “Your verse fractured him.” The beatniks decide a shrine must be built to their new king of beat poetry – and so construct “The Most” coffee house on the hallowed hollow. Before premiering their new poetic find to the world, the beatniks realize a change in Snuffy’s appearance is in order. Those threads have to go – that is, go in the other sense, not as in “go” for more poetry. A sweater, black trousers, and sandals become Snuffy’s new wardrobe. Still, something is missing, thanks to Snuffy’s bald head. More hair, and a beard. Fortunately, it turns out that each of the beatniks is wearing hair that is partially fake – so one provides Snuffy with his wig, while the other loans Snuffy his fake beard.

Snuffy seems all set, but along comes Loweezy, looking for him. Snuffy leaps into Loweezy’s arms – but Loweezy doesn’t recognize him. She drops him on the ground, apologizing that her Snuffy doesn’t like her to talk to strangers, and continues on, calling for Snuffy. Snuffy begins to weep, thinking he’s lost his woman. He sings a few lines of the song “Clementine” about “lost and gone forever”, substituting Loweezy’s name instead of Clementine. The beatniks are even more sent than before, noting that Snuffy wails even better when he’s suffering.

Snuffy falls asleep again under his favorite tree. Loweezy comes back, still in search of Snuffy, and finally is not fooled by Snuffy’s new look, as she’d know his snoring anywhere. She observes he has visually transformed into a beatnik, and proves to be far more savvy of the sub-culture than her spouse, deciding to match Snuffy’s career move. Within a few moments, she reappears, dressed in identical sweater, pants and sandals to Snuffy, but topping things off with a beret, a pair of dark glasses, and a guitar. Snuffy awakens and can hardly recognize her for the clothes and the beat talk, but the beatniks hail her as the coolest of wives. So the coffee house opens, attracting not only an audience of beatniks, but with half the seats occupied by hillbilly mountaineers. Snuffy and Loweezy appear on stage, back-to-back in seated recline against each other, with Loweezy strumming guitar while bongos and flute play in the background. They perform a “beat” recitation of “Old MacDonald Had a Farm”. Their read receives the usual finger snaps and hails of “cool”. But a mishap spells the end for the venue. An espresso machine overheats, its heating pipes popping off the tank with loud bangs. Some of the hillbillies mistake the sound for shots, and rifles are raised, as a criss-cross of gunfire fills the club interior, many bullets finding their mark in the espresso machine, puncturing holes in it. The paying customers beat a retreat out the door into the hills, leaving only the two beatniks to raise their cups to the streams of java leaking from the espresso machine. One of them is inspired to poetry by the evening’s events, and starts to recite, “The Farmer in the Dell” to a typical irregular beatnik rhythm. “Beautiful, man, beautiful”, says the other, the two apparently realizing they can satisfy their own poetry needs from now on. The final scene finds Snuffy and Loweezy together on their porch back home, in their old outfits, with Snuffy on Loweezy’s lap. Loweezy asks Snuffy how he’s feeling. With drooping eyelids, Snuffy responds. “Tired. Like, what else – beat!”, and falls asleep on Loweezy’s shoulder.

Snuffy falls asleep again under his favorite tree. Loweezy comes back, still in search of Snuffy, and finally is not fooled by Snuffy’s new look, as she’d know his snoring anywhere. She observes he has visually transformed into a beatnik, and proves to be far more savvy of the sub-culture than her spouse, deciding to match Snuffy’s career move. Within a few moments, she reappears, dressed in identical sweater, pants and sandals to Snuffy, but topping things off with a beret, a pair of dark glasses, and a guitar. Snuffy awakens and can hardly recognize her for the clothes and the beat talk, but the beatniks hail her as the coolest of wives. So the coffee house opens, attracting not only an audience of beatniks, but with half the seats occupied by hillbilly mountaineers. Snuffy and Loweezy appear on stage, back-to-back in seated recline against each other, with Loweezy strumming guitar while bongos and flute play in the background. They perform a “beat” recitation of “Old MacDonald Had a Farm”. Their read receives the usual finger snaps and hails of “cool”. But a mishap spells the end for the venue. An espresso machine overheats, its heating pipes popping off the tank with loud bangs. Some of the hillbillies mistake the sound for shots, and rifles are raised, as a criss-cross of gunfire fills the club interior, many bullets finding their mark in the espresso machine, puncturing holes in it. The paying customers beat a retreat out the door into the hills, leaving only the two beatniks to raise their cups to the streams of java leaking from the espresso machine. One of them is inspired to poetry by the evening’s events, and starts to recite, “The Farmer in the Dell” to a typical irregular beatnik rhythm. “Beautiful, man, beautiful”, says the other, the two apparently realizing they can satisfy their own poetry needs from now on. The final scene finds Snuffy and Loweezy together on their porch back home, in their old outfits, with Snuffy on Loweezy’s lap. Loweezy asks Snuffy how he’s feeling. With drooping eyelids, Snuffy responds. “Tired. Like, what else – beat!”, and falls asleep on Loweezy’s shoulder.

• “Beauty and The Beat” is on DailyMotion

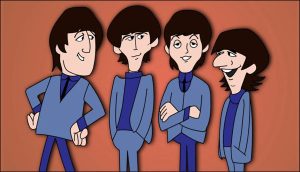

Coverage of King Features cartoons would not be complete without at least an honorable mention for “The Beatles”. This really could not be said to be a show about getting with the times – the Beatles WERE the times. I generally in my youth was not one to follow cartoons making current-day celebrities into cartoon characters. (That’d be the day you’d see me watching Mr. T, the Jackson Five, Punky Brewster, Gary Coleman, or even The Partridge Family in Outer Space.) But the phenomenon of the Beatles was such a 600-pound gorilla when unleashed upon Saturday morning that I recall no other network being willing to put on anything of quality in my broadcast area to compete against it. So. I actually found myself sometimes watching it – as a stopgap to get to the next program I would actually enjoy at the end of the half-hour. I was not particularly taken with the music. (As I may have mentioned in another post, rock and roll was not a big or often-discussed form of entertainment, or even classified as music, in my household, and while I probably had knowledge of “She Loves You” and “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” from endless plays on radio, and later of “A Hard Day’s Night” from incessant plugging of the movie, the rest of the catalog was pretty unknown to me – and to a degree still is except for a couple of “greatest hits” sets.) So, I found the musical interludes to be intrusive, and felt like they were a waste of airtime as a mere plug for the group. (I would later feel the same when musical moments would be mandatory drop-ins to shows such as “The Archie Show”. “Josie and the Pussycats”, and early episodes of “Scooby-Doo” – even though by that time most such numbers were being originally written rather than included as plugs for existing recordings.) I would thus wait for the so-called “comedy” in the first and third cartoons – which ultimately turned out to be sparce at best.

Coverage of King Features cartoons would not be complete without at least an honorable mention for “The Beatles”. This really could not be said to be a show about getting with the times – the Beatles WERE the times. I generally in my youth was not one to follow cartoons making current-day celebrities into cartoon characters. (That’d be the day you’d see me watching Mr. T, the Jackson Five, Punky Brewster, Gary Coleman, or even The Partridge Family in Outer Space.) But the phenomenon of the Beatles was such a 600-pound gorilla when unleashed upon Saturday morning that I recall no other network being willing to put on anything of quality in my broadcast area to compete against it. So. I actually found myself sometimes watching it – as a stopgap to get to the next program I would actually enjoy at the end of the half-hour. I was not particularly taken with the music. (As I may have mentioned in another post, rock and roll was not a big or often-discussed form of entertainment, or even classified as music, in my household, and while I probably had knowledge of “She Loves You” and “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” from endless plays on radio, and later of “A Hard Day’s Night” from incessant plugging of the movie, the rest of the catalog was pretty unknown to me – and to a degree still is except for a couple of “greatest hits” sets.) So, I found the musical interludes to be intrusive, and felt like they were a waste of airtime as a mere plug for the group. (I would later feel the same when musical moments would be mandatory drop-ins to shows such as “The Archie Show”. “Josie and the Pussycats”, and early episodes of “Scooby-Doo” – even though by that time most such numbers were being originally written rather than included as plugs for existing recordings.) I would thus wait for the so-called “comedy” in the first and third cartoons – which ultimately turned out to be sparce at best.

I could never really discern any personality given by the animators to John, Paul, or George, who seemed to serve as three identical straight-men. Only Ringo stood out, with his Liverpool accent making him “sound funny” to a juvenile ear, and by making him the dumb fool and the fall guy. This seemed to be the only saving grace of the show – and it has not been enough to drag me back to studying the old episodes now that they have finally surfaced and come out of hiding on the internet. Another of my childhood observations has been reinforced by a few recent internet viewings – the animation and directing was downright terrible. King Features probably thought their visual style was trendy, giving the look of British poster art. I merely found the movement stilted, the outlines too thick and ragged, and the angles, cutting and timing of the shots something that made the storylines (such as they were) hard to follow. King Features’ later production, “Cool McCool”, followed in the same visual style somewhat, but it seemed like the overall effect had been toned down and refined by then, with better stories, less frenetic cutting and pacing, and maybe even a bit better inking – making the cartoons more palatable. The “running” gags in every show about constantly being pursued by women didn’t help things for me a bit. Nothing evoked the same comedy sense as seeing 1940’s characters swooning over Sinatra. It more closely approximated a sense of paranoia – which might have been summarized best by a later lyric from Elvis Presley (“Caught in a trap – I can’t get out.”). All in all, “The Beatles” was a product of its time, self-promotional and intended for (or to create) the die-hard fan, and deserved to die when the newness of the Fab Four began to fade. It has left no lasting legacy besides plugging the music – and I dare say animation buffs who lost track of it in its many years of absence from availability probably felt no dramatic loss in having to rely upon their dim, distant memories to certify that it ever existed. Yet, it accomplished its ultimate purpose – the bucks rolled in.

I could never really discern any personality given by the animators to John, Paul, or George, who seemed to serve as three identical straight-men. Only Ringo stood out, with his Liverpool accent making him “sound funny” to a juvenile ear, and by making him the dumb fool and the fall guy. This seemed to be the only saving grace of the show – and it has not been enough to drag me back to studying the old episodes now that they have finally surfaced and come out of hiding on the internet. Another of my childhood observations has been reinforced by a few recent internet viewings – the animation and directing was downright terrible. King Features probably thought their visual style was trendy, giving the look of British poster art. I merely found the movement stilted, the outlines too thick and ragged, and the angles, cutting and timing of the shots something that made the storylines (such as they were) hard to follow. King Features’ later production, “Cool McCool”, followed in the same visual style somewhat, but it seemed like the overall effect had been toned down and refined by then, with better stories, less frenetic cutting and pacing, and maybe even a bit better inking – making the cartoons more palatable. The “running” gags in every show about constantly being pursued by women didn’t help things for me a bit. Nothing evoked the same comedy sense as seeing 1940’s characters swooning over Sinatra. It more closely approximated a sense of paranoia – which might have been summarized best by a later lyric from Elvis Presley (“Caught in a trap – I can’t get out.”). All in all, “The Beatles” was a product of its time, self-promotional and intended for (or to create) the die-hard fan, and deserved to die when the newness of the Fab Four began to fade. It has left no lasting legacy besides plugging the music – and I dare say animation buffs who lost track of it in its many years of absence from availability probably felt no dramatic loss in having to rely upon their dim, distant memories to certify that it ever existed. Yet, it accomplished its ultimate purpose – the bucks rolled in.

The premiere episode in the series is embedded below.

Lest we forget, there was also the knock-off. Total Television’s last effort, “The Beagles”, on CBS. You could already tell it was cheap when the number of “performers” was halved from four to two. There was no Ringo to rely upon for dumb laughs, and little-guy Tubby was no Jerry Lewis (though his voice was styled to be) when it came to trying to get smiles by being scared or taking it on the chin. There was only one plot – manager Scotty would plan some dangerous new publicity stunt to plug the Beagles’ latest song, while the two performers would face all the peril. Every single week. God help anyone on Scotty’s client list. I found him to be totally heartless, and not in a funny money-grubbing way like perhaps a Hokey Wolf. It was a feeble concept, and after a couple weeks, I grew quickly tired of it. It aired late in the broadcast day, so at least if you could see (as you normally did) that it was more of the same old thing, you could tune out on it, and get on with your daily routine. This is probably what the rest of America did too, accounting for its short single-season of episodes, and its now virtually-forgotten status. It spawned one hard-to-find LP of original songs, and, quite honestly, the music wasn’t so bad judged by the contemporary standards of its day – certainly more memorable than any of Hanna-Barbera’s later rock efforts, and to me, most of the Archies’ material. Perhaps because of the music rights, it received no re-syndication or rebroadcast on Total’s compilation shows such as “Cartoon Cutups”, and only less than a handful of episodes have surfaced on the internet to date. The only one currently available in color (though the print is about a full second out of sync), and the only presently-available complete story (as most storylines consisted of four parts instead of two) is embedded as a sample below.

Lest we forget, there was also the knock-off. Total Television’s last effort, “The Beagles”, on CBS. You could already tell it was cheap when the number of “performers” was halved from four to two. There was no Ringo to rely upon for dumb laughs, and little-guy Tubby was no Jerry Lewis (though his voice was styled to be) when it came to trying to get smiles by being scared or taking it on the chin. There was only one plot – manager Scotty would plan some dangerous new publicity stunt to plug the Beagles’ latest song, while the two performers would face all the peril. Every single week. God help anyone on Scotty’s client list. I found him to be totally heartless, and not in a funny money-grubbing way like perhaps a Hokey Wolf. It was a feeble concept, and after a couple weeks, I grew quickly tired of it. It aired late in the broadcast day, so at least if you could see (as you normally did) that it was more of the same old thing, you could tune out on it, and get on with your daily routine. This is probably what the rest of America did too, accounting for its short single-season of episodes, and its now virtually-forgotten status. It spawned one hard-to-find LP of original songs, and, quite honestly, the music wasn’t so bad judged by the contemporary standards of its day – certainly more memorable than any of Hanna-Barbera’s later rock efforts, and to me, most of the Archies’ material. Perhaps because of the music rights, it received no re-syndication or rebroadcast on Total’s compilation shows such as “Cartoon Cutups”, and only less than a handful of episodes have surfaced on the internet to date. The only one currently available in color (though the print is about a full second out of sync), and the only presently-available complete story (as most storylines consisted of four parts instead of two) is embedded as a sample below.

NEXT WEEK: We’ll look into Hanna-Barbera’s takes on culture shock and new trends.