The early ‘50’s found some returns to past themes of social awkwardness and old-timey ways previously visited by other characters in the past, as well as a few new wrinkles involving breakthroughs in aviation, juvenile delinquency, child psychology, and of course, the latest musical trends. Disney, Terrytoons, and Walter Lantz each figure heavily in today’s mix. all carefully watching whatever social media there was in the day to keep abreast of new subjects to keep their product fresh and current, and to keep their stars from comfortably settling into any ruts.

Hero For a Day (Terrytoons, Fox, Mighty Mouse, 3/3/52 – Mannie Davis, dir.) – Popeye had previously faced the pressure of rivaling his Paramount stable-mate Superman (even if impersonated by Bluto) for the bragging rights of strongest guy on the block. A country mouse (voiced in similar fashion to Edgar Bergen’s ventriloquist dummy Mortimer Snerd – the inspiration for Beaky Buzzard) faces the same pressure at Terrytoos from the fame of the studio’s biggest super-hero – Mighty Mouse – and must likewise try to match himself to the Mouse of Steel to impress his girl. Our rural bumpkin visits his girlfriend Susie, armed with a bouquet of posies. He receives a cool reception, when he discovers his girl has received an autographed picture of Mighty Mouse, and developed a crush on his muscular physique. “What’s he got that I haven’t got?”, the little mouse asks, and flexes an arm muscle that looks more like a wart. Giggling, his girlfriend presses on the muscle, easily forcing it to descend from an upper-arm bulge into a lower-arm droop. “Take it easy. That’s the only muscle I’ve got”, complains our spurned Romeo. As his girl returns to embracing the photograph, the country mouse sadly drops his bouquet and wanders away. In his travels, he encounters the attention of three cats who wouldn’t mind adding him to their menu. However, the little mouse remains largely unaware of their attentions, as their leaps overshoot him or cause the cats to merely butt heads together. What does attract out little mouse’s attention is a toy store window, displaying a line of Mighty Mouse dolls. “That gives me an idea”, says the mouse. Slipping under the front door, the mouse re-emerges, carrying a new yellow and red wardrobe, while in the store window, one doll has been reduced to his underwear.

Hero For a Day (Terrytoons, Fox, Mighty Mouse, 3/3/52 – Mannie Davis, dir.) – Popeye had previously faced the pressure of rivaling his Paramount stable-mate Superman (even if impersonated by Bluto) for the bragging rights of strongest guy on the block. A country mouse (voiced in similar fashion to Edgar Bergen’s ventriloquist dummy Mortimer Snerd – the inspiration for Beaky Buzzard) faces the same pressure at Terrytoos from the fame of the studio’s biggest super-hero – Mighty Mouse – and must likewise try to match himself to the Mouse of Steel to impress his girl. Our rural bumpkin visits his girlfriend Susie, armed with a bouquet of posies. He receives a cool reception, when he discovers his girl has received an autographed picture of Mighty Mouse, and developed a crush on his muscular physique. “What’s he got that I haven’t got?”, the little mouse asks, and flexes an arm muscle that looks more like a wart. Giggling, his girlfriend presses on the muscle, easily forcing it to descend from an upper-arm bulge into a lower-arm droop. “Take it easy. That’s the only muscle I’ve got”, complains our spurned Romeo. As his girl returns to embracing the photograph, the country mouse sadly drops his bouquet and wanders away. In his travels, he encounters the attention of three cats who wouldn’t mind adding him to their menu. However, the little mouse remains largely unaware of their attentions, as their leaps overshoot him or cause the cats to merely butt heads together. What does attract out little mouse’s attention is a toy store window, displaying a line of Mighty Mouse dolls. “That gives me an idea”, says the mouse. Slipping under the front door, the mouse re-emerges, carrying a new yellow and red wardrobe, while in the store window, one doll has been reduced to his underwear.

At home, the little mouse tries on hs new heroic apparel, adding the finishing touch by inflating a large balloon inside the chest cavity of the shirt, and two smaller balloons inside the sleeves. “If its muscles she wants, muscles she’s gonna get”, vows the mouse. Arranging a slingshot in the ground, the mouse plans a heroic entrance by air to arrive at his girl’s front door. The grace of the entrance is spoiled when the balloons cause him to bounce on the landing like a rubber ball. “You’ll never be a mighty mouse”, laughs his girl. But a sight over our star’s shoulder wipes the smile off of the girl’s face, and causes her to duck for cover back into the safety of her home. The three cats have gotten together on things, and arrived all at once to confront the little mouse. The little mouse chooses this inopportune moment to boast, “It there were only some cats around here, I’d show ya. You’d see.” Looking up, he discovers he’s just gotten his wish. “A muscle man”, jeers one of the cats. The mouse’s heart leaps into his throat, but, realizing he still has the suit, he tries to call the cats’ bluff. “Don’t start nothin’ with me or I’ll flatten ya”, he declares. Regrettably, he gestures to himself with an outstretched thumb to the chest – and pops the largest balloon, leaving a torn hole and a sagging midriff in his super suit. Two of the cats pop out their claws like switchblade knives, and each pops one of the remaining shoulder balloons. The mouse is left a tattered, scrawny mess. Just to test out what the mouse has got in him without his suit, one cat pushes his face close to the mouse, and bats an eyelash at him – which is more than enough to knock the little mouse down.

At home, the little mouse tries on hs new heroic apparel, adding the finishing touch by inflating a large balloon inside the chest cavity of the shirt, and two smaller balloons inside the sleeves. “If its muscles she wants, muscles she’s gonna get”, vows the mouse. Arranging a slingshot in the ground, the mouse plans a heroic entrance by air to arrive at his girl’s front door. The grace of the entrance is spoiled when the balloons cause him to bounce on the landing like a rubber ball. “You’ll never be a mighty mouse”, laughs his girl. But a sight over our star’s shoulder wipes the smile off of the girl’s face, and causes her to duck for cover back into the safety of her home. The three cats have gotten together on things, and arrived all at once to confront the little mouse. The little mouse chooses this inopportune moment to boast, “It there were only some cats around here, I’d show ya. You’d see.” Looking up, he discovers he’s just gotten his wish. “A muscle man”, jeers one of the cats. The mouse’s heart leaps into his throat, but, realizing he still has the suit, he tries to call the cats’ bluff. “Don’t start nothin’ with me or I’ll flatten ya”, he declares. Regrettably, he gestures to himself with an outstretched thumb to the chest – and pops the largest balloon, leaving a torn hole and a sagging midriff in his super suit. Two of the cats pop out their claws like switchblade knives, and each pops one of the remaining shoulder balloons. The mouse is left a tattered, scrawny mess. Just to test out what the mouse has got in him without his suit, one cat pushes his face close to the mouse, and bats an eyelash at him – which is more than enough to knock the little mouse down.

A chase ensues, in which the mouse stumbles over a rock, and knocks himself unconscious on the ground, The three cats race in for the kill, and leap in a group pounce toward their target. Who should arrive, ever vigilant and without even a distress call, to save the day? “It’s him!” “In person!” “MIGHTY MOUSE!!”, shout the cats, freezing in mid-air before reaching their victim. The three cats turn and, still suspended by nothing but air, attempt to quietly tiptoe away – until gravity takes over and lands them on the ground. One cat gets the same treatment from Mighty that he gave to the little mouse – with Mighty knocking him over with a mere flick of a finger. The other two cats charge Mighty with a battering ram, but Mighty launches into a forward spin, transforming into a spinning saw-blade and cutting the log in two.

A chase ensues, in which the mouse stumbles over a rock, and knocks himself unconscious on the ground, The three cats race in for the kill, and leap in a group pounce toward their target. Who should arrive, ever vigilant and without even a distress call, to save the day? “It’s him!” “In person!” “MIGHTY MOUSE!!”, shout the cats, freezing in mid-air before reaching their victim. The three cats turn and, still suspended by nothing but air, attempt to quietly tiptoe away – until gravity takes over and lands them on the ground. One cat gets the same treatment from Mighty that he gave to the little mouse – with Mighty knocking him over with a mere flick of a finger. The other two cats charge Mighty with a battering ram, but Mighty launches into a forward spin, transforming into a spinning saw-blade and cutting the log in two.

The first cat tosses a wooden spear at our hero. Mighty grabs the spear in mid-air, then launches it back at the cat. The cat ducks into a hollow tree, as the spear flies into the hole, then protrudes out the other side of the tree, the cat’s fur hanging like a bedraggled garment from the spear point, as the cat emerges from the tree hole in red flannel underwear to retrieve his “garment”. From inside a barrel, another cat fires at Mighty with a rifle. Mighty socks the bullets out of his flight path, then bends back the barrel of the gun to point directly into the wooden barrel. Another shot from the gun blasts the barrel apart, leaving the cat in a duplication of Tom and Jerry’s old “sunflower” gag, with the cat’s blackened face in the center of a circle of board “petals”. A leap by another cat causes Mighty to belt the cat skyward under the overhanging branches of a nearby tree. The cat soars upward, knocking branch after branch off the tree with his head. The wooden debris falling from the tree assembles and takes the shape of a wooden wheel chair with the battered cat landing in the driver’s seat. The cat wheels himself away for a hasty exit, encounters a rock obstacle, and bounces onto another rock, knocked unconscious. Mighty delivers finishing blows to the other two cats, who land atop the shoulders of the first cat, forming a feline totem pole.

The first cat tosses a wooden spear at our hero. Mighty grabs the spear in mid-air, then launches it back at the cat. The cat ducks into a hollow tree, as the spear flies into the hole, then protrudes out the other side of the tree, the cat’s fur hanging like a bedraggled garment from the spear point, as the cat emerges from the tree hole in red flannel underwear to retrieve his “garment”. From inside a barrel, another cat fires at Mighty with a rifle. Mighty socks the bullets out of his flight path, then bends back the barrel of the gun to point directly into the wooden barrel. Another shot from the gun blasts the barrel apart, leaving the cat in a duplication of Tom and Jerry’s old “sunflower” gag, with the cat’s blackened face in the center of a circle of board “petals”. A leap by another cat causes Mighty to belt the cat skyward under the overhanging branches of a nearby tree. The cat soars upward, knocking branch after branch off the tree with his head. The wooden debris falling from the tree assembles and takes the shape of a wooden wheel chair with the battered cat landing in the driver’s seat. The cat wheels himself away for a hasty exit, encounters a rock obstacle, and bounces onto another rock, knocked unconscious. Mighty delivers finishing blows to the other two cats, who land atop the shoulders of the first cat, forming a feline totem pole.

So what to do about the little mouse who wanted to be mighty? Leave him placed at the foot of the totem pole, to awaken to find his adversaries vanquished. More surprised than the little mouse is his girlfriend, who finally looks out her door to see the amazing sight. “You’re my big strong hero”, she says to the little mouse, embracing him. “Gosh, I didn’t know I had it in me”, replies the mouse. The girl plants several kisses on him – and then more girls from the community also surround him with attention. “Take it easy” he cheerily tells the,. “One at a time. There’s room for everybody!” From behind a tree, Mighty gives the audience a wink, and, with another job well done, heads off in search of his next adventure.

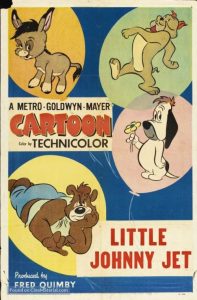

Little Johnny Jet (MGM. 4/18/53 – Tex Avery, dir.) – What do you do when WWII is over, if you happen to be “an old, burnt-out B-29″? This riveting question is answered in high-polished detail by gag king Tex Avery in an Academy Award-nominated gem, providing his own spin on the basic idea of Disney’s “Pedro”, coupled with a splash of his own previous success at updating the automotive precursor of “Cars”, Warner’s “Streamlined Greta Green”, into his own “One Cab’s Family”. Planes thus come to life, with eyes instead of windshields, minds of their own, and full domestic lives to attend to. The film opens on the flight of a decorated fighter plane of the great conflict (masterfully voiced by Daws Butler), descending wearily to his home airfield, lifting the door of a hangar like the garage door of a house to admit himself in. His missus, a female plane of similar design, greets him and asks how his day went. (Notably, the respective planes are named John and Mary – allowing for a running gag of repetitions of their names in all manner of variances of mood and intonation, paralleling Daws’ frequent partner Stan Freberg’s hit comedy recording for Capitol. “John and Marsha”, consisting entirely of the two names in varying emotional reads.) Despite displaying to prospective employers his war record, and even his beating purple heart inside his bomb bay, no airport in town has any openings for work for John. Our hero plane has found himself outclassed by the latest thing – jets, which are all the airports will hire. To make matters more complicated, he finds Mary concealing an item of knitting – the equivalent of a baby bootie, shaped like a little plane. A blessed event is on the way. Good news, and bad news, as this means “Another propeller to feed.” Now the prospective Papa has to get a job. Mary suggests that he could always reenlist, which raises Papa’s patriotic fervor. “Back to the old Air Corps!” But he receives no more welcome at the recruiting office than in the private sector, where they rubber stamp his tail “Rejected” and boot him out the door, as they are only recruiting jets.

Little Johnny Jet (MGM. 4/18/53 – Tex Avery, dir.) – What do you do when WWII is over, if you happen to be “an old, burnt-out B-29″? This riveting question is answered in high-polished detail by gag king Tex Avery in an Academy Award-nominated gem, providing his own spin on the basic idea of Disney’s “Pedro”, coupled with a splash of his own previous success at updating the automotive precursor of “Cars”, Warner’s “Streamlined Greta Green”, into his own “One Cab’s Family”. Planes thus come to life, with eyes instead of windshields, minds of their own, and full domestic lives to attend to. The film opens on the flight of a decorated fighter plane of the great conflict (masterfully voiced by Daws Butler), descending wearily to his home airfield, lifting the door of a hangar like the garage door of a house to admit himself in. His missus, a female plane of similar design, greets him and asks how his day went. (Notably, the respective planes are named John and Mary – allowing for a running gag of repetitions of their names in all manner of variances of mood and intonation, paralleling Daws’ frequent partner Stan Freberg’s hit comedy recording for Capitol. “John and Marsha”, consisting entirely of the two names in varying emotional reads.) Despite displaying to prospective employers his war record, and even his beating purple heart inside his bomb bay, no airport in town has any openings for work for John. Our hero plane has found himself outclassed by the latest thing – jets, which are all the airports will hire. To make matters more complicated, he finds Mary concealing an item of knitting – the equivalent of a baby bootie, shaped like a little plane. A blessed event is on the way. Good news, and bad news, as this means “Another propeller to feed.” Now the prospective Papa has to get a job. Mary suggests that he could always reenlist, which raises Papa’s patriotic fervor. “Back to the old Air Corps!” But he receives no more welcome at the recruiting office than in the private sector, where they rubber stamp his tail “Rejected” and boot him out the door, as they are only recruiting jets.

As John trudges home, grumbling over his hatred of jets, he spies the arrival of a helicopter shaped like a stork, dropping a bundle through a hatch in his hangar roof. The new addition to the family is here. John opens the bundle to get a look at his offspring, but is absolutely startled when the fledgling takes off out the hangar door and across the field at nearly supersonic speed. John and Mary duck for cover as the baby makes several more passes in and out of the hangar, then finally comes in for a landing. John is about to praise his son’s skill, when he observes for the first time, “No propeller”. Mary breaks the news to him that Junior is – what else – a jet. At the top of his lungs, Papa screams, “Jets1 Jets! I can’t stand JETS!” Papa drops out of the realm of parental pride, into his own world of solitary sulking, and loathing of the invention that has cost him his livelihood.

A typical morning finds Papa mulling over the morning paper, barely tolerating the constant fly-bys of Junior, who never seems to put his wheels on the ground. Mama adjusts to the new routine, holding up spoons of baby food for Junior to swallow on every pass, then changing diapers by grabbing one off him as he swishes by, then holding up another for him to fly into on the next pass. Meanwhile, John reads the latest aviation news, announcing in headline a round the world air race, with the winner to receive a huge government contract. Of course, the world’s fastest jets are expected to compete. But John, seeing only through eyes red with rage, takes off toward the site of the starting line, grumbling, “I’ll show ‘em.” Mama can’t understand his sudden departure, until she also reads the headline. Placing Junior in a baby carriage, Mary tells her son that they have to stop his father, or he’ll kill himself in that race.

A typical morning finds Papa mulling over the morning paper, barely tolerating the constant fly-bys of Junior, who never seems to put his wheels on the ground. Mama adjusts to the new routine, holding up spoons of baby food for Junior to swallow on every pass, then changing diapers by grabbing one off him as he swishes by, then holding up another for him to fly into on the next pass. Meanwhile, John reads the latest aviation news, announcing in headline a round the world air race, with the winner to receive a huge government contract. Of course, the world’s fastest jets are expected to compete. But John, seeing only through eyes red with rage, takes off toward the site of the starting line, grumbling, “I’ll show ‘em.” Mama can’t understand his sudden departure, until she also reads the headline. Placing Junior in a baby carriage, Mary tells her son that they have to stop his father, or he’ll kill himself in that race.

At the event site, John is pleasantly surprised to see a familiar face – another similar bomber, wearing the hat and glasses of General Douglas MacArthur and smoking his style of pipe. Saluting him, John asks, “Morning, sir. Are you flying today?” Paraphrasing MacArthur’s famous quite about “Old soldiers never die”, the plane responds, “Old planes never fly. They just fade away” – which the general then does, literally, right before our eyes. The sleek streamlined jets line up at the starting line, while John sputters his way into position. Mary and Junior arrive, and Mary tries to dissuade John out of this foolhardy plan, not noticing that Junior has opened the door in the side of Papa, and stepped inside. (This always seemed to me a little unnerving – would this qualify as a male pregnancy?) As the racers are told to get on their marks, Mary spots Junior waving to her from the inside of a glass gunner’s turret in Papa’s roof. But she is unable to stop John in time, and the two take off into the blue together – though not quite as planned. As John strains to bring his engines up to speed, the force of the exertion pulls both propeller pods right off his wings, and they each go sailing off into the sky without their owner. With no propulsion, John falls helplessly like a stone. Inside, Junior realizes Papa’s plight, and struggles with Papa’s door to push it open. At the last second, Junior emerges from the side, grabbing hold of John’s tail, and pushing him back into the air, inches from collision with the ground. He waves to his startled dad, and a truce and admiration society are finally struck between father and son, who just saved his Papa’s life. Noting Junior’s tremendous speed despite the extra weight of Papa, John pushes his gunner canopy forward as if wearing a hat at a rakish angle, and says, “Let’s get ‘em, son.”

At the event site, John is pleasantly surprised to see a familiar face – another similar bomber, wearing the hat and glasses of General Douglas MacArthur and smoking his style of pipe. Saluting him, John asks, “Morning, sir. Are you flying today?” Paraphrasing MacArthur’s famous quite about “Old soldiers never die”, the plane responds, “Old planes never fly. They just fade away” – which the general then does, literally, right before our eyes. The sleek streamlined jets line up at the starting line, while John sputters his way into position. Mary and Junior arrive, and Mary tries to dissuade John out of this foolhardy plan, not noticing that Junior has opened the door in the side of Papa, and stepped inside. (This always seemed to me a little unnerving – would this qualify as a male pregnancy?) As the racers are told to get on their marks, Mary spots Junior waving to her from the inside of a glass gunner’s turret in Papa’s roof. But she is unable to stop John in time, and the two take off into the blue together – though not quite as planned. As John strains to bring his engines up to speed, the force of the exertion pulls both propeller pods right off his wings, and they each go sailing off into the sky without their owner. With no propulsion, John falls helplessly like a stone. Inside, Junior realizes Papa’s plight, and struggles with Papa’s door to push it open. At the last second, Junior emerges from the side, grabbing hold of John’s tail, and pushing him back into the air, inches from collision with the ground. He waves to his startled dad, and a truce and admiration society are finally struck between father and son, who just saved his Papa’s life. Noting Junior’s tremendous speed despite the extra weight of Papa, John pushes his gunner canopy forward as if wearing a hat at a rakish angle, and says, “Let’s get ‘em, son.”

Now, Avery cuts loose with a potpourri of his trademark sight gags on the round the world jaunt. Other jets are passed so quickly, one has to leap into another’s wings to dodge out of the way. Another is “scalped” by Junior’s passing, revealing a bald spot along the top of its fuselage. A skywriter’s advertisement “Drink Zippy Cola” is converted by Junior’s passing into the word “Burp”. A rainbow is tied into a bowknot. The smog cover is lifted off of Los Angeles. A U.S. Navy blimp is cut in two, revealing its center to be made of watermelon. The leaning tower of Pisa is tilted by Junior in the opposite direction, The Sphinx also receives a crew cur. The Eiffel Tower spreads its “leg” supports to let Junior through. (I’ve always wondered if one gag is missing here, as two gagless aerial shots of Junior turning and changing direction over the continents are oddly placed back to back – could Avery have originally included a gag on Africa, which he was usually fond of including in many a cartoon?) Junior passes over a long ocean liner, compressing it from the force of his passing into a tugboat. As they enter the home stretch, Junior blows up the skirts of the Statue of Liberty, revealing a pink bathing suit underneath. John and Junior soar to the finish line unopposed, receiving the cheers of the crowd. “That’s my boy”, John proudly points to Junior. The government contract is awarded – with an unexpected proviso – the Air Force needs ten thousand baby jets immediately! “Ten thousand!” shouts a dismayed John, and nervously looks at his wife. Mary blushes deeply, but is up to the task – revealing that she has already been knitting a string of ten thousand airplane baby booties! The order is on the way.

Now, Avery cuts loose with a potpourri of his trademark sight gags on the round the world jaunt. Other jets are passed so quickly, one has to leap into another’s wings to dodge out of the way. Another is “scalped” by Junior’s passing, revealing a bald spot along the top of its fuselage. A skywriter’s advertisement “Drink Zippy Cola” is converted by Junior’s passing into the word “Burp”. A rainbow is tied into a bowknot. The smog cover is lifted off of Los Angeles. A U.S. Navy blimp is cut in two, revealing its center to be made of watermelon. The leaning tower of Pisa is tilted by Junior in the opposite direction, The Sphinx also receives a crew cur. The Eiffel Tower spreads its “leg” supports to let Junior through. (I’ve always wondered if one gag is missing here, as two gagless aerial shots of Junior turning and changing direction over the continents are oddly placed back to back – could Avery have originally included a gag on Africa, which he was usually fond of including in many a cartoon?) Junior passes over a long ocean liner, compressing it from the force of his passing into a tugboat. As they enter the home stretch, Junior blows up the skirts of the Statue of Liberty, revealing a pink bathing suit underneath. John and Junior soar to the finish line unopposed, receiving the cheers of the crowd. “That’s my boy”, John proudly points to Junior. The government contract is awarded – with an unexpected proviso – the Air Force needs ten thousand baby jets immediately! “Ten thousand!” shouts a dismayed John, and nervously looks at his wife. Mary blushes deeply, but is up to the task – revealing that she has already been knitting a string of ten thousand airplane baby booties! The order is on the way.

• “Little Johnny Jet” is viewable on Facebook.

How to Dance (Disney/RKO, Goofy, 7/11/53 – Jack Kinney, dir.) – Goofy finds himself in the same embarrassing situation as faced by Popeye, nearly 20 years earlier. Narrator Art Gilmore tells of the history of dancing, originating from primitive rituals of the stone age as a means of expressing one’s self. However, moving into the modern age, he observes that some people have lost their natural instincts and ability to dance away their cares. Witness Goofy, alone at a table in a night club while all his friends make with the rhythm on the dance floor. A girl asks him to dance, and he shyly hides his head, then shakes it in a “no”, displaying a large leg cast as a “feeble excuse” (considering that the cast is empty, and his leg rests safely below the tablecloth). He is left holding the bags, and stuck with the check for his party. He looks down at his shoes, and an x-ray view reveals a literal two left feet within. Goof resolves to take the big step – learn ro dance.

How to Dance (Disney/RKO, Goofy, 7/11/53 – Jack Kinney, dir.) – Goofy finds himself in the same embarrassing situation as faced by Popeye, nearly 20 years earlier. Narrator Art Gilmore tells of the history of dancing, originating from primitive rituals of the stone age as a means of expressing one’s self. However, moving into the modern age, he observes that some people have lost their natural instincts and ability to dance away their cares. Witness Goofy, alone at a table in a night club while all his friends make with the rhythm on the dance floor. A girl asks him to dance, and he shyly hides his head, then shakes it in a “no”, displaying a large leg cast as a “feeble excuse” (considering that the cast is empty, and his leg rests safely below the tablecloth). He is left holding the bags, and stuck with the check for his party. He looks down at his shoes, and an x-ray view reveals a literal two left feet within. Goof resolves to take the big step – learn ro dance.

He begins with home instruction. Placing a record on a turntable, he studies a chart in a dance instruction book, that looks about as simple as the pattern for the average pro-football play in any animated cartoon. Taking a scissor to a stack of paper, Goofy cuts out paper-doll style footprint images, and begins scattering them everywhere on the floor. Unfortunately, he has chosen a room with an open patio door, and a considerable draft blowing in. The paper patterns begin to move and shift throughout the room, Goofy helplessly attempting to follow in these “footsteps” wherever they lead. He spins and swivels his way out the front door, into a corridor of his apartment building, and lands a swift kick upon the rear end of a man who happens to be bent over, with one of the paper footprints resting on the seat of his pants. This last dance move earns Goofy a good conk on the noggin from the irritated neighbor.

For the next lesson, Goofy selects a dancing partner – or at least improvises one, in the form of a dressmaker’s dummy, with a hollow where arms should attach, and no head. The thing swivels around on rollers, so Goofy is able to lead it by placing his arm through the hollow shoulders of the dummy, and grasping the hand protruding from the dummy with his other free hand. His respective arms seem to develop personalities of their own, corresponding to opposite genders, with the hand within the dummy smacking Goofy across the face when he seems to get too fresh. The narrator suggests offering his date refreshments. Goofy serves up a drink, pouring it down the empty collar of the dummy. The dummy’s roller-legs begin to buckle and sway, as if intoxicated. The dummy’s wheel catches in an electrical socket, giving Goofy a surprise shock when he again extends his arm inside. Goofy spins around dizzily with smoke gathering as if on fire – then the dummy explodes and disintegrates to a skeletal frame. Goofy lies on the floor, but is impressed by this energetic response, remarking to the camera, “What a gal!”

For the next lesson, Goofy selects a dancing partner – or at least improvises one, in the form of a dressmaker’s dummy, with a hollow where arms should attach, and no head. The thing swivels around on rollers, so Goofy is able to lead it by placing his arm through the hollow shoulders of the dummy, and grasping the hand protruding from the dummy with his other free hand. His respective arms seem to develop personalities of their own, corresponding to opposite genders, with the hand within the dummy smacking Goofy across the face when he seems to get too fresh. The narrator suggests offering his date refreshments. Goofy serves up a drink, pouring it down the empty collar of the dummy. The dummy’s roller-legs begin to buckle and sway, as if intoxicated. The dummy’s wheel catches in an electrical socket, giving Goofy a surprise shock when he again extends his arm inside. Goofy spins around dizzily with smoke gathering as if on fire – then the dummy explodes and disintegrates to a skeletal frame. Goofy lies on the floor, but is impressed by this energetic response, remarking to the camera, “What a gal!”

Home methods having proved difficult, Goofy attends an accredited dancing school. Machines run him through the paces of Russian dancing, Irish jigs (initiated by a string of bullets shot at his feet by pistols), ballet (suspended from a theatrical sky hook), and the Mexican hat dance (strung up like a marionette). He makes progress with a real dancing partner, although her own grace of movement is a bit mechanically-aided (she is shown in backlit silhouette to be not dancing at all, but seated upon and riding on a wheeled stool concealed below her skirt). Finally he graduates (or at least, is kicked out the front door). He returns to the night club, confidently asks a lady out onto the dance floor, and consults a quick set of refresher-course dance charts etched upon a rotating cuff of his suit’s shirt. The music begins – but the guest band of the evening is Ward Kimball’s raucous dixieland aggregation, The Firehouse Five Plus Two! The dixieland rhythm causes a stampede on the crowded floor, and Goofy is kicked, trampled, and finally sinks below the sea of humanity, going down for the third time. The camera pulls back, revealing the dancers and the scenery outside the ballroom window to be identical to the primitive scene with which we began the film at the beginning of time. The narrator concludes. “From primitive man to modern man – Man, you’ve come a long way, in only ten thousand years.”

Home methods having proved difficult, Goofy attends an accredited dancing school. Machines run him through the paces of Russian dancing, Irish jigs (initiated by a string of bullets shot at his feet by pistols), ballet (suspended from a theatrical sky hook), and the Mexican hat dance (strung up like a marionette). He makes progress with a real dancing partner, although her own grace of movement is a bit mechanically-aided (she is shown in backlit silhouette to be not dancing at all, but seated upon and riding on a wheeled stool concealed below her skirt). Finally he graduates (or at least, is kicked out the front door). He returns to the night club, confidently asks a lady out onto the dance floor, and consults a quick set of refresher-course dance charts etched upon a rotating cuff of his suit’s shirt. The music begins – but the guest band of the evening is Ward Kimball’s raucous dixieland aggregation, The Firehouse Five Plus Two! The dixieland rhythm causes a stampede on the crowded floor, and Goofy is kicked, trampled, and finally sinks below the sea of humanity, going down for the third time. The camera pulls back, revealing the dancers and the scenery outside the ballroom window to be identical to the primitive scene with which we began the film at the beginning of time. The narrator concludes. “From primitive man to modern man – Man, you’ve come a long way, in only ten thousand years.”

• “How To Dance” is on DailyMotion.

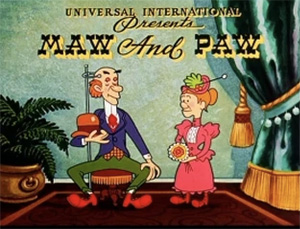

Maw and Paw (Lantz/Universal, 8/10/53 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – The first in an all-too- brief four cartoon run of animated adventures of the visual equivalents of the popular Ma and Pa Kettle live-action series, the animated edition including the Kettles’ humongous family, and a new addition – an intelligent pet pig named Milford (billed in this first episode as “The Smart One” – telling us the average intelligence of the rest of the family.) For this and their second appearance (discussed below), the Kettles (though never called by such name in the cartoons) try to cope in their backwards rustic manner with the advances of modern technology.

Maw and Paw (Lantz/Universal, 8/10/53 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – The first in an all-too- brief four cartoon run of animated adventures of the visual equivalents of the popular Ma and Pa Kettle live-action series, the animated edition including the Kettles’ humongous family, and a new addition – an intelligent pet pig named Milford (billed in this first episode as “The Smart One” – telling us the average intelligence of the rest of the family.) For this and their second appearance (discussed below), the Kettles (though never called by such name in the cartoons) try to cope in their backwards rustic manner with the advances of modern technology.

We are introduced to the family on a typical morning, with Paw drying out laundry by hanging it from the string of a flying kite tied around his big toe, while he snoozes beneath a tree. Maw is busy simultaneously churning butter, giving a baby a bottle (balanced on her head), and whipping up a bowl of grits for breakfast (with the consistency of melted rubber). Everyone chows down at the breakfast table, with all the table manners of a boarding house, excepting Milford, who delicately slices his food in observance of pure etiquette. The wall telephone rings, and everyone passes to another the task of answering it, finally leaving the chore to Milford. The call is from a radio quiz show, asking the prize question, “How many tails does a dog have?” An “Oink” from Milford is close enough to the word “one” to win the jackpot prize – a brand-new Roadhog super automobile.

Milford, who can only squeal, has a devil of a time trying to communicate to Paw the prize he has won, finally grabbing away the pie tin of Paw’s dessert and puttering around the floor as if using the tin for a steering wheel. Fortunately, a tow truck delivering the prize outside clears up any confusion. The family stampedes over Paw to inspect the new mechanical wonder, leaving Paw to step on a loose porch floorboard and smack himself in the nose, catching his smeller in a knothole. Maw remarks, “You aimin’ to fix that board this year, Paw?” Milford, who presumably has no driver’s license, seems to nevertheless be the most knowledgeable about vehicles of any of them, and assumes the driver’s seat. This car has an automatic button for everything. First, power windows (which do their best job of blocking Paw’s entry into the vehicle). Maw, busy using the radio antenna as a new-fangled clothesline, is ejected by a power hood release, launched across the farm, and straight into a large pig mudhole. Paw soon follows, flipped by a power convertible roof to the same mudhole location, and knocking Maw back in just as she is beginning to climb out. Paw returns to the vehicle, switches seats with Milford, and asks Milford to start ‘er up by pushing a mess of them buttons. Milford presses one which administers an automatic barber-style shave to Paw with robotic hands, then springs him out of the car again with an ejector seat. Paw lands back at the mudhole, knocking Maw in once again. Paw looks down at her and remarks, “Sure gonna get pretty takin’ all them mud baths, Maw.” Maw’s only reaction is to sock Paw in the nose. Suddenly, Milford finally finds the right button, and the car’s engine turns over with a roar. Milford grabs the wheel, and finds himself steering a runaway vehicle, eventually in pursuit of the whole family. Maw winds up in the mudhole again, while Paw and the others climb high into a tree. The car approaches the tree at full speed, and crashes head-on into the trunk. The force of the impact warps and compresses the block-long vehicle into the shape of a two-seater Model T Touring car, comfortably seating the entire family as they fall out of the tree. Paw takes the wheel, and the jalopy sputters its way across the farm – making a bee-line straight into the mudhole, with the entire family joining Maw in the wallow.

Milford, who can only squeal, has a devil of a time trying to communicate to Paw the prize he has won, finally grabbing away the pie tin of Paw’s dessert and puttering around the floor as if using the tin for a steering wheel. Fortunately, a tow truck delivering the prize outside clears up any confusion. The family stampedes over Paw to inspect the new mechanical wonder, leaving Paw to step on a loose porch floorboard and smack himself in the nose, catching his smeller in a knothole. Maw remarks, “You aimin’ to fix that board this year, Paw?” Milford, who presumably has no driver’s license, seems to nevertheless be the most knowledgeable about vehicles of any of them, and assumes the driver’s seat. This car has an automatic button for everything. First, power windows (which do their best job of blocking Paw’s entry into the vehicle). Maw, busy using the radio antenna as a new-fangled clothesline, is ejected by a power hood release, launched across the farm, and straight into a large pig mudhole. Paw soon follows, flipped by a power convertible roof to the same mudhole location, and knocking Maw back in just as she is beginning to climb out. Paw returns to the vehicle, switches seats with Milford, and asks Milford to start ‘er up by pushing a mess of them buttons. Milford presses one which administers an automatic barber-style shave to Paw with robotic hands, then springs him out of the car again with an ejector seat. Paw lands back at the mudhole, knocking Maw in once again. Paw looks down at her and remarks, “Sure gonna get pretty takin’ all them mud baths, Maw.” Maw’s only reaction is to sock Paw in the nose. Suddenly, Milford finally finds the right button, and the car’s engine turns over with a roar. Milford grabs the wheel, and finds himself steering a runaway vehicle, eventually in pursuit of the whole family. Maw winds up in the mudhole again, while Paw and the others climb high into a tree. The car approaches the tree at full speed, and crashes head-on into the trunk. The force of the impact warps and compresses the block-long vehicle into the shape of a two-seater Model T Touring car, comfortably seating the entire family as they fall out of the tree. Paw takes the wheel, and the jalopy sputters its way across the farm – making a bee-line straight into the mudhole, with the entire family joining Maw in the wallow.

• “Maw and Paw” may be found in a 16mm scan on Facebook.

Plywood Panic (Lantz/Universal, Maw and Paw, 9/26/53 – Paul J. Smith, dir.), follows a similar formula. For saving one million box tops from Hominy Grit Pops cereal (a parody of Kellogg’s Rice Krispies), the family wins a new house. At the presentation ceremony, Maw notices something is wrong, when only a picture of the dwelling is displayed by the sponsor. “But where’s the house?”, she asks. The sponsor points to a vacant lot, over which is strewn a wide variety of huge packing crates. The house is pre-fabricated, assembly required. Essentially, the film becomes something of a poor-man’s remake of Mickey Mouse’s “Boat Builders”, with a dash of Fleischer’s “The House Builder-Upper” and Famous’s “House Trucks?” thrown in. Everything unfolds, including interior plumbing, staircases, easy chair, and picket fence – with the family kids quick to activate the unfolding buttons with shots from slingshots and peashooters. Maw is at one point flung into the air, and falls through a blueprint held by Paw, punching a hole through it and landing on the ground. Paw peers through the hole, and asks “What are ya doin’ down there in the basement, Maw?” Maw also gets stuck with her feet in the slots where a gate should fit in the picket fence. Paw steps up the front walk, swinging Maw as if she were the missing gate, and hears a rusty-sounding squeak from her feet. “Gotta oil that gate one of these days”, observes Paw. A running gag also finds that Paw still hasn’t repaired the loose porch board on the original house, and carries the curse to his new abode, where a bird house on the roof suffers from the same loose board for its residents, and Paw’s final entrance into the new home uproots a similar loose board in the new porch, bringing the whole house down in the same manner as Mickey’s boat and Popeye’s two houses. Maw emerges from the rubble, and is asked by Paw what she is doing on the roof. Paw receives another well-deserved sock in the nose for his remark, and a fade out.

Plywood Panic (Lantz/Universal, Maw and Paw, 9/26/53 – Paul J. Smith, dir.), follows a similar formula. For saving one million box tops from Hominy Grit Pops cereal (a parody of Kellogg’s Rice Krispies), the family wins a new house. At the presentation ceremony, Maw notices something is wrong, when only a picture of the dwelling is displayed by the sponsor. “But where’s the house?”, she asks. The sponsor points to a vacant lot, over which is strewn a wide variety of huge packing crates. The house is pre-fabricated, assembly required. Essentially, the film becomes something of a poor-man’s remake of Mickey Mouse’s “Boat Builders”, with a dash of Fleischer’s “The House Builder-Upper” and Famous’s “House Trucks?” thrown in. Everything unfolds, including interior plumbing, staircases, easy chair, and picket fence – with the family kids quick to activate the unfolding buttons with shots from slingshots and peashooters. Maw is at one point flung into the air, and falls through a blueprint held by Paw, punching a hole through it and landing on the ground. Paw peers through the hole, and asks “What are ya doin’ down there in the basement, Maw?” Maw also gets stuck with her feet in the slots where a gate should fit in the picket fence. Paw steps up the front walk, swinging Maw as if she were the missing gate, and hears a rusty-sounding squeak from her feet. “Gotta oil that gate one of these days”, observes Paw. A running gag also finds that Paw still hasn’t repaired the loose porch board on the original house, and carries the curse to his new abode, where a bird house on the roof suffers from the same loose board for its residents, and Paw’s final entrance into the new home uproots a similar loose board in the new porch, bringing the whole house down in the same manner as Mickey’s boat and Popeye’s two houses. Maw emerges from the rubble, and is asked by Paw what she is doing on the roof. Paw receives another well-deserved sock in the nose for his remark, and a fade out.

Fortunately, the last two Maw and Paw cartoons did not follow formula, and were quite original and clever. Why the series did not continue remains a mystery (especially as the live action films continued into 1957). Perhaps the large number of characters in the films made Lantz feel costs were prohibitive. Or, the writers were at a bit of a lack for further ideas. It seems unlikely that audience reaction was not positive to them, as they were usually dependable laugh-getters, and had something of a position of prominence in their runs on the original Woody Woodpecker Show. The true reason for the series’ mysterious disappearance may never be known.

• “Plywood Panic” is at https://vk.com/ or on Internet Archive.

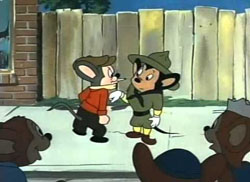

Spare the Rod (Terrytoons/Fox, Mighty Mouse, 9/8/53 – Connie Rasinski, dir.), must rank among the most mature of short subjects in the series’ history – as it is doubtful any mother would have wanted it to be seen by an impressionable young child of grade school or pre-school age withot some explanation, for the possibility of giving the child too many bad ideas by example. Ahead of its time, the film deals with the rise of juvenile delinquency among students. The topic would within a year receive more widespread national prominence, through the publication of a novel, and within a short time thereafter, release of a feature film, entitled “Blackboard Jungle.” For many years., I had assumed this film to be a parody of such work, never realizing until now that it was instead predicting things to come. It is among the most Interesting, different, and well-plotted scripts for the character, depite remaining a bit disturbing in its content.

Spare the Rod (Terrytoons/Fox, Mighty Mouse, 9/8/53 – Connie Rasinski, dir.), must rank among the most mature of short subjects in the series’ history – as it is doubtful any mother would have wanted it to be seen by an impressionable young child of grade school or pre-school age withot some explanation, for the possibility of giving the child too many bad ideas by example. Ahead of its time, the film deals with the rise of juvenile delinquency among students. The topic would within a year receive more widespread national prominence, through the publication of a novel, and within a short time thereafter, release of a feature film, entitled “Blackboard Jungle.” For many years., I had assumed this film to be a parody of such work, never realizing until now that it was instead predicting things to come. It is among the most Interesting, different, and well-plotted scripts for the character, depite remaining a bit disturbing in its content.

A narrator describes this as the story of a town that had to take a stand, as its juveniles were getting badly out of hand. They congregated at pool halls and places respectable mice wouldn’t go, to smoke, gamble and fight – and other things one wouldn’t care to know. The opening sequence shows them causing a riot in the pool hall, breaking up everything in sight. The owner tries to chase them out, but as he yells “Stop!”, his mouth is filled with a barrage of billiard balls. He is smacked by a pool cue atop one of the tables, where another mouse molds him into a triangle with a pool rack, while a third shoots the cue ball at him, breaking him into 15 colored spheres which disappear down the pockets of the table, and reassemble as himself from out of the ball chute.

The scene moves to the classroom, where the students are also entirely uncontrollable. Students smoke at their desks, read the comics, and pelt each other with slingshot and peashooter fire. A professor enters with a cheery, “Good morning, children”, only to be battered by a stream of flying textbooks, pencils, eggs, ink bottles, tomatoes, and even an alarm clock. The teacher attempts to crawl away toward the door, but a student grabs his coattail, tying it to the pull string of a hanging chart, which rolls up like a windowshade, trapping the professor inside. One student has made chalk drawings of nine teachers in a grid on the blackboard, one of whom already has an X drawn through his image, and adds a second X through the picture of the professor we have just seen. A heavy-set, gruff-looking female teacher enters the doorway. “Bring ‘em on”, jeers one of the students. She calls for the class to come to order, but a mouse lounging on her desk while eating lunch replies, “Go on home, ya old battle-axe.” Taking a pepper shaker, the mouse shakes out its whole contents into the path of an electric fan, blowing the pepper right into the teacher’s nose. She inhales and delivers a powerful sneeze, so forceful that she is blasted through the wall of the schoolroom and out of the building. The mouse at the blackboard crosses a X through her picture, completing a tic tac toe line on the grid.

The scene moves to the classroom, where the students are also entirely uncontrollable. Students smoke at their desks, read the comics, and pelt each other with slingshot and peashooter fire. A professor enters with a cheery, “Good morning, children”, only to be battered by a stream of flying textbooks, pencils, eggs, ink bottles, tomatoes, and even an alarm clock. The teacher attempts to crawl away toward the door, but a student grabs his coattail, tying it to the pull string of a hanging chart, which rolls up like a windowshade, trapping the professor inside. One student has made chalk drawings of nine teachers in a grid on the blackboard, one of whom already has an X drawn through his image, and adds a second X through the picture of the professor we have just seen. A heavy-set, gruff-looking female teacher enters the doorway. “Bring ‘em on”, jeers one of the students. She calls for the class to come to order, but a mouse lounging on her desk while eating lunch replies, “Go on home, ya old battle-axe.” Taking a pepper shaker, the mouse shakes out its whole contents into the path of an electric fan, blowing the pepper right into the teacher’s nose. She inhales and delivers a powerful sneeze, so forceful that she is blasted through the wall of the schoolroom and out of the building. The mouse at the blackboard crosses a X through her picture, completing a tic tac toe line on the grid.

The scene changes to a public meeting hall, where P.T.A. members, the Lions’ Club, Rotary Club, Kiwanis Club, Citizen’s League, and other concerned parents and citizens (including delegations with signs reading “Pelham”, “Eastchester, N.Y.”, and “New Rochelle” (the home of the Terrytoons studio)) congregate, demanding action. A consensus is reached that they need a leader, brave and strong, to show these kids right from wrong – one who’s got the stuff to handle kids so tough. Who else but Mighty Mouse? And so, Mighty resorts to unusual incognito tactics, infiltrating the delinquent’s territory, disguised as the un-coolest of characters – a boy scout. Their reaction is as expected – “Let’s give him da works.” Their toughest member comes forward, a chip of wood placed on his shoulder. “Go on, knock it off”, the bully challenges. Mighty obliges, but in an unexpected way – removing the bully from under the piece of wood rather tha vice versa, with a mere flick of his finger. The shocked tough guy rises from the pavement, and lands a right directly on Mighty’s jaw. Mighty does not move, and the blow results in a loud metallic clang, as the bully’s hand swells up in red, and he exits the frame repeatedly yelling “OW!”. Pairs of other mice approach with wooden clubs, but Mighty ducks each of the swings, letting the mice’s blows fall upon each other. The fallen mice converge upon Mighty in a fight cloud, but as the dust clears. Mighty, still looking untouched, is last man standing. Only a pair of mice dropping a heavy iron stove from a second story window above brings Mighty to a momentary incapacitation, trapping him between steel and pavement.

A police whistle is heard, and one mouse calls out, “Cheese it! The cops”. The mice hurriedly hijack a moving van, with one climbing into the cab and the others into the cargo compartment, and the vehicle takes off at high speed for a getaway. Only one problem – the mouse in front has never driven a truck before, and the vehicle careens out of control. To make things doubly perilous, one mouse is tossed out of the rear as the truck bounces over the tracks at a railroad crossing. His foot lands in the worst of places – wedged between the track rail and wooden slats providing the road bed for the auto crossing, rendering him unable to move – while an approaching train is heard in the distance. Now Mighty, who finally frees himself from the stove, little realizes that he is going to have to save the day twice. Removing his scout disguise, Mighty soars into the skies, first spotting the runaway van. The vehicle is on a collision course with a telephone pole. Mighty zooms from the sky, and snaps off the pole just inches before the van can hit it, as the truck passes over the corner and continues down the road. Mighty flies under the moving chassis and grabs hold of the rear axle/transmission. Pulling backwards does not stop the vehicle due to its onrushing speed, but instead severs the body frame of the truck from the chassis. Nevertheless, luck is with Mighty, as the chassis makes contact with the road, and, despite a bumpy ride, grinds gradually to a halt, with no one hurt. But there’s still the matter of the kid left behind at the railroad tracks. The poor mouse is on his knees saying his prayers, with the train whistle looming ever closer in the distance. Mighty flies back along the road at full speed, then spots the cross-track of the train. Soaring to the train’s position, Mighty first reaches the caboose end, and desperately tries to stop the train by pulling backwards on the caboose’s bumper. He only succeeds in uncoupling the car, while the engine and remaining cars advance at full steam. Mighty now finds himself in a race with the careening train, inching forward car length by car length to reach the engine.

A police whistle is heard, and one mouse calls out, “Cheese it! The cops”. The mice hurriedly hijack a moving van, with one climbing into the cab and the others into the cargo compartment, and the vehicle takes off at high speed for a getaway. Only one problem – the mouse in front has never driven a truck before, and the vehicle careens out of control. To make things doubly perilous, one mouse is tossed out of the rear as the truck bounces over the tracks at a railroad crossing. His foot lands in the worst of places – wedged between the track rail and wooden slats providing the road bed for the auto crossing, rendering him unable to move – while an approaching train is heard in the distance. Now Mighty, who finally frees himself from the stove, little realizes that he is going to have to save the day twice. Removing his scout disguise, Mighty soars into the skies, first spotting the runaway van. The vehicle is on a collision course with a telephone pole. Mighty zooms from the sky, and snaps off the pole just inches before the van can hit it, as the truck passes over the corner and continues down the road. Mighty flies under the moving chassis and grabs hold of the rear axle/transmission. Pulling backwards does not stop the vehicle due to its onrushing speed, but instead severs the body frame of the truck from the chassis. Nevertheless, luck is with Mighty, as the chassis makes contact with the road, and, despite a bumpy ride, grinds gradually to a halt, with no one hurt. But there’s still the matter of the kid left behind at the railroad tracks. The poor mouse is on his knees saying his prayers, with the train whistle looming ever closer in the distance. Mighty flies back along the road at full speed, then spots the cross-track of the train. Soaring to the train’s position, Mighty first reaches the caboose end, and desperately tries to stop the train by pulling backwards on the caboose’s bumper. He only succeeds in uncoupling the car, while the engine and remaining cars advance at full steam. Mighty now finds himself in a race with the careening train, inching forward car length by car length to reach the engine.

The crossing is only a short distance ahead, and Mighty still has not reached the cab. Instead, he darts under the train’s wheels. A crowd of the kids have reached the junction, and stand in shock and terror as the train passes them unabated, staring at car after car whizzing past, and seeing nothing of the slaughter that they presume is going on underneath. But as the last car passes, standing on the other side of the tracks is Mighty, carrying the formerly trapped boy in his arms, in the clear. The kids cheer and celebrate Mighty’s daring rescue of them all. The scene reurns to the classroom, where a short time has passed, and the students have turned over an entirely new leaf. Their old professor now receives a table full of apples, candy, flowers, and thank-you notes. The students, all dressed in boy scout uniforms, sing Good Morning with angel halos glowing above their heads. All except one in the back row, who, despite his boy scout uniform, is about to revert to his old ways by flinging an ink bottle at the teacher. He finds he is not alone, as Mighty appears, looking over his shoulder and shaking his head in disapproval. The little mouse is not about to challenge the wishes of his hero, and makes amends by smashing the ink bottle over his own head, leaving his face stained in bright blue, while he obediently finishes the song lyric, “Because we love our school”, for the fade out.

The crossing is only a short distance ahead, and Mighty still has not reached the cab. Instead, he darts under the train’s wheels. A crowd of the kids have reached the junction, and stand in shock and terror as the train passes them unabated, staring at car after car whizzing past, and seeing nothing of the slaughter that they presume is going on underneath. But as the last car passes, standing on the other side of the tracks is Mighty, carrying the formerly trapped boy in his arms, in the clear. The kids cheer and celebrate Mighty’s daring rescue of them all. The scene reurns to the classroom, where a short time has passed, and the students have turned over an entirely new leaf. Their old professor now receives a table full of apples, candy, flowers, and thank-you notes. The students, all dressed in boy scout uniforms, sing Good Morning with angel halos glowing above their heads. All except one in the back row, who, despite his boy scout uniform, is about to revert to his old ways by flinging an ink bottle at the teacher. He finds he is not alone, as Mighty appears, looking over his shoulder and shaking his head in disapproval. The little mouse is not about to challenge the wishes of his hero, and makes amends by smashing the ink bottle over his own head, leaving his face stained in bright blue, while he obediently finishes the song lyric, “Because we love our school”, for the fade out.

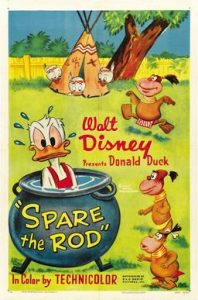

Spare the Rod (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 1/15/54 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – I wonder what kind of havoc (if any) the release of two rival films using the identical title within the span of four months might have caused with distributors and film rental companies. Did any theatres wishing to show the Donald Dick cartoon wind up with a copy of Mighty Mouse instead? Or vice versa? Sounds worse than the counter-bookings of Ub Iwerks’ ‘The Little Red Hen” versus Disney’s “The Wise Little Hen” in the 1930’s. The subject of new interest to Donald for this adventure is modern child training – and whether or not it is survivable. An odd entry in the series, first for its use of some slide-like intertitles and deliberately corny narration from Bill Thompson, and secondly, as one of the last racially politically-incorrect cartoons to be produced involving cannibals. We open at Donald’s house, where everyone is supposed to be doing their chores. But the log pile where Huey, Louie, and Dewey are supposed to be chopping firewood has been deserted. They are off playing at being island natives in a makeshift grass hut, dancing a savage dance to tom-tom beat with wooden knives flashing about. Donald’s steadiness of hand is disturbed by the drum beats while painting a window frame, and he retaliates by using his paints to create a horrific tiki face upon the top lid of an old barrel, lifting it to the door of the hut and uttering angry roars to scare the kids out and back to work. But the effect doesn’t last long, and soon the boys have abandoned their work again, now playing pirate on a home-made replica of a ship’s deck. Donald prepares to wage war upon them again, when he is stopped in his tracks by the appearance of a miniature duck-spirit in a college cap and gown (also voiced by Bill Thompson), announcing himself as the Voice of Child Psychology. The tiny egghead spirit suggests that the way to get the kids’ cooperation is not to treat them rough, but to win their confidence, join in their games, and be a pal. At the spirit’s prompting, Donald joins in the pirate games, wearing a patch over one eye and carrying a parrot puppet – but his first effort only succeeds in having him walk the plank into a bucket of water.

Spare the Rod (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 1/15/54 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – I wonder what kind of havoc (if any) the release of two rival films using the identical title within the span of four months might have caused with distributors and film rental companies. Did any theatres wishing to show the Donald Dick cartoon wind up with a copy of Mighty Mouse instead? Or vice versa? Sounds worse than the counter-bookings of Ub Iwerks’ ‘The Little Red Hen” versus Disney’s “The Wise Little Hen” in the 1930’s. The subject of new interest to Donald for this adventure is modern child training – and whether or not it is survivable. An odd entry in the series, first for its use of some slide-like intertitles and deliberately corny narration from Bill Thompson, and secondly, as one of the last racially politically-incorrect cartoons to be produced involving cannibals. We open at Donald’s house, where everyone is supposed to be doing their chores. But the log pile where Huey, Louie, and Dewey are supposed to be chopping firewood has been deserted. They are off playing at being island natives in a makeshift grass hut, dancing a savage dance to tom-tom beat with wooden knives flashing about. Donald’s steadiness of hand is disturbed by the drum beats while painting a window frame, and he retaliates by using his paints to create a horrific tiki face upon the top lid of an old barrel, lifting it to the door of the hut and uttering angry roars to scare the kids out and back to work. But the effect doesn’t last long, and soon the boys have abandoned their work again, now playing pirate on a home-made replica of a ship’s deck. Donald prepares to wage war upon them again, when he is stopped in his tracks by the appearance of a miniature duck-spirit in a college cap and gown (also voiced by Bill Thompson), announcing himself as the Voice of Child Psychology. The tiny egghead spirit suggests that the way to get the kids’ cooperation is not to treat them rough, but to win their confidence, join in their games, and be a pal. At the spirit’s prompting, Donald joins in the pirate games, wearing a patch over one eye and carrying a parrot puppet – but his first effort only succeeds in having him walk the plank into a bucket of water.

Meanwhile, a circus train chugs past town. In one cage of the train rides a trio of genuine pigmy cannibals. One of them reaches out between the bars to pull out the pin connecting their cage to the rest of the train. The cage rolls back downhill along the tracks, derails, and crashes open, releasing the pigmies. They begin a war chant, and proceed into town, passing the gate of Donald’s home. One spies Donald working in his yard, and the three of them envision Donald in roasted form. Inside the yard, the psychology spirit reappears, spotting the cannibals first. Due to the pigmies’ tiny size, the spirit jumps to the conclusion that they are the nephews again in a new game, now in disguise. He alerts Donald that the boys are back, and convinces Donald that playing along is the perfect setup to get the firewood chopped – as a cannibal pot will need firewood to boil. Donald not only cooperates at spearpoint, but drags in a cooking pot himself, and fills it with water from a garden hose. Then, he convinces the “boys” to go cut the firewood. The spirit congratulates Donald on the success of the plan, as the cannibals get busy chopping. On the other side of the yard, the real nephews are now playing Indians. They spot Donald in the pot, and take him out as hostage, tying him to a stake in their play-encampment. They too will need firewood to burn their captive, so also begin chopping away. The spirit now has double reasons for congratulating Donald, with the assurance that now there should be enough firewood chopped to last all winter. But the cannibals return to the pot to find it empty. Searching the yard, they find Donald tied to the stake. Lifting the stake out of the ground, they carry it and the still-tied Donald back to the pot, dumping them inside. The nephews return to the camp to find their hostage gone, and attempt to take Donald back, resulting in a tug of war over the stake between the nephews and the cannibals.

Meanwhile, a circus train chugs past town. In one cage of the train rides a trio of genuine pigmy cannibals. One of them reaches out between the bars to pull out the pin connecting their cage to the rest of the train. The cage rolls back downhill along the tracks, derails, and crashes open, releasing the pigmies. They begin a war chant, and proceed into town, passing the gate of Donald’s home. One spies Donald working in his yard, and the three of them envision Donald in roasted form. Inside the yard, the psychology spirit reappears, spotting the cannibals first. Due to the pigmies’ tiny size, the spirit jumps to the conclusion that they are the nephews again in a new game, now in disguise. He alerts Donald that the boys are back, and convinces Donald that playing along is the perfect setup to get the firewood chopped – as a cannibal pot will need firewood to boil. Donald not only cooperates at spearpoint, but drags in a cooking pot himself, and fills it with water from a garden hose. Then, he convinces the “boys” to go cut the firewood. The spirit congratulates Donald on the success of the plan, as the cannibals get busy chopping. On the other side of the yard, the real nephews are now playing Indians. They spot Donald in the pot, and take him out as hostage, tying him to a stake in their play-encampment. They too will need firewood to burn their captive, so also begin chopping away. The spirit now has double reasons for congratulating Donald, with the assurance that now there should be enough firewood chopped to last all winter. But the cannibals return to the pot to find it empty. Searching the yard, they find Donald tied to the stake. Lifting the stake out of the ground, they carry it and the still-tied Donald back to the pot, dumping them inside. The nephews return to the camp to find their hostage gone, and attempt to take Donald back, resulting in a tug of war over the stake between the nephews and the cannibals.

The spirit reappears, and realizes something is mathematically amiss. “Three Indians and three cannibals….You got six nephews?”. he asks Donald. The answer is obvious, and everyone suddenly realizes the cannibals are real. The spirit and the nephews flee in panic, leaving Donald at the mercy of the savages. Donald has an apple stuffed in his mouth, yet mumbles a prayer with hands together amidst the binding ropes. The fire is lit, and one of the cannibals performs a taste test upon Donald by biting his foot. Donald shouts in pain, and bursts out of his bonds, grabbing up the cannibals. To teach them a lesson, he carries them off to the woodshed, where the sounds of a loud spanking are heard amidst the shed’s violent vibrations. The three cannibals exit and disappear down the railroad tracks, holding onto their painful rear ends. Donald confronts the nephews, impatiently stamping his foot. The boys know better than to cross Donald in this state of temper, and resume their woodchopping at a vigorous triple-tempo. The spirit appears again, but, rather than give praise to Donald’s old-fashioned approach, tries to claim the credit. “See how my modern psychology works?” “What?”, says Donald, seizing up the spirit in one hand. The spirit sheepishly shrugs his shoulders, changing his tune. “Oh, well, your psychology, my psychology…What’s the difference?” “I’ll show ya’ the difference”, quacks Donald, and returns with the spirit to the woodshed, where we hear the spirit’s shouts as another loud spanking is administered, for the iris out.

The spirit reappears, and realizes something is mathematically amiss. “Three Indians and three cannibals….You got six nephews?”. he asks Donald. The answer is obvious, and everyone suddenly realizes the cannibals are real. The spirit and the nephews flee in panic, leaving Donald at the mercy of the savages. Donald has an apple stuffed in his mouth, yet mumbles a prayer with hands together amidst the binding ropes. The fire is lit, and one of the cannibals performs a taste test upon Donald by biting his foot. Donald shouts in pain, and bursts out of his bonds, grabbing up the cannibals. To teach them a lesson, he carries them off to the woodshed, where the sounds of a loud spanking are heard amidst the shed’s violent vibrations. The three cannibals exit and disappear down the railroad tracks, holding onto their painful rear ends. Donald confronts the nephews, impatiently stamping his foot. The boys know better than to cross Donald in this state of temper, and resume their woodchopping at a vigorous triple-tempo. The spirit appears again, but, rather than give praise to Donald’s old-fashioned approach, tries to claim the credit. “See how my modern psychology works?” “What?”, says Donald, seizing up the spirit in one hand. The spirit sheepishly shrugs his shoulders, changing his tune. “Oh, well, your psychology, my psychology…What’s the difference?” “I’ll show ya’ the difference”, quacks Donald, and returns with the spirit to the woodshed, where we hear the spirit’s shouts as another loud spanking is administered, for the iris out.

An honorable mention goes to Real Gone Woody (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 9/20/54 – Paul J. Smith, dir,), though it may not completely fit our subject category – as both of its protagonists, Woody Woodpecker and Buzz Buzzard, seem to have largely adapted to the high-school scene of the 1950’s, and the musical fads predominating those days. It is, however, definitely a landmark time-capsule of its period, with both boys trying to measure up in a contest of coolness within the eyes of their mutually-admired sweetheart, Winnie Woodpecker. (A similar vibe was registered by Disney’s segment from “Make Mine Music”. “All the Cats Join In” – but said earlier film falls further from meeting our subject category, in that everyone in it is decidedly cool, except for one brief walk-on by a square still hip to the Charleston, who is quickly ushered out the door and never seen again.)

An honorable mention goes to Real Gone Woody (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 9/20/54 – Paul J. Smith, dir,), though it may not completely fit our subject category – as both of its protagonists, Woody Woodpecker and Buzz Buzzard, seem to have largely adapted to the high-school scene of the 1950’s, and the musical fads predominating those days. It is, however, definitely a landmark time-capsule of its period, with both boys trying to measure up in a contest of coolness within the eyes of their mutually-admired sweetheart, Winnie Woodpecker. (A similar vibe was registered by Disney’s segment from “Make Mine Music”. “All the Cats Join In” – but said earlier film falls further from meeting our subject category, in that everyone in it is decidedly cool, except for one brief walk-on by a square still hip to the Charleston, who is quickly ushered out the door and never seen again.)

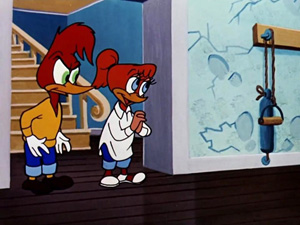

Michael Maltese provides the brilliant and action-packed script for our Woody epic. Winnie Woodecker is introduced for the first time – a typical bobby-soxer, lounging around with her back on the floor and her legs propped up on an easy chair, getting phone calls inviting her to the big sock jop dance at school this weekend. Woody gets his call in first, and Winnie accepts. Woody is flipped over the news, and styles his topknot in a pompadour that resembles the shape of a duck (known as a “D.A. haircut”, or duck’s “posterior”). Crew-cut Buzz Buzzard is miffed at hearing Winnie has accepted Woody’s invitation, and talks her into considering him as runner-up in case Woody doesn’t show for the date. Buzz quickly inspects his crew cut, taking care of one stray upright hair by hammering it like a nail back into his head, and is off in his souped-up car to beat Woody to Winnie’s house.

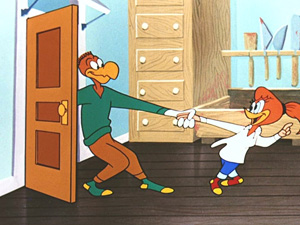

Woody drives a car of his own that is a unique accumulation of old and new parts. The fenders, whitewall tires and chrome hubcaps are modern. But between them rests the classless chassis of an old Model T. Buzz zooms past Woody, remarking, “Dig that crazy washing machine!”, and arrives first at Winnie’s door, adding the remark back in Woody’s direction, “Drop dead, drip.” He enters Winnie’s living room, instantly striking up a lively dance with the damsel, and lying to her that Woody couldn’t make it. Woody pulls to a stop outside behind Buzz’s car, knocking off about twelve chrome exhaust pipes from Buzz’s vehicle. Before entering the house, Woody takes the security precaution of removing his own car’s chrome hubcaps, and locking them in a safe built into the car’s rear trunk. He then enters the home, and a brawl begins between Woody and Buzz. Winnie frowns on this, and insists they stop, or she won’t go out with either one of them. She then gets an idea that seems to please no one but herself – why don’t they all go to the sock hop together? The boys grumble at each other while Winnie smiles and giggles, each boy making it clear to the other that this isn’t over yet.

Woody drives a car of his own that is a unique accumulation of old and new parts. The fenders, whitewall tires and chrome hubcaps are modern. But between them rests the classless chassis of an old Model T. Buzz zooms past Woody, remarking, “Dig that crazy washing machine!”, and arrives first at Winnie’s door, adding the remark back in Woody’s direction, “Drop dead, drip.” He enters Winnie’s living room, instantly striking up a lively dance with the damsel, and lying to her that Woody couldn’t make it. Woody pulls to a stop outside behind Buzz’s car, knocking off about twelve chrome exhaust pipes from Buzz’s vehicle. Before entering the house, Woody takes the security precaution of removing his own car’s chrome hubcaps, and locking them in a safe built into the car’s rear trunk. He then enters the home, and a brawl begins between Woody and Buzz. Winnie frowns on this, and insists they stop, or she won’t go out with either one of them. She then gets an idea that seems to please no one but herself – why don’t they all go to the sock hop together? The boys grumble at each other while Winnie smiles and giggles, each boy making it clear to the other that this isn’t over yet.

Outside, Buzz proposes they all go in his car. Woody wants otherwise, and offers to “flip” Buzz for it. He does so, giving Buzz a judo flip to the ground, and nabs off Winnie alone, driving her to the school with a honk of his custom car horn, which mimics the notes of his trademark laugh. At the campus, the gymnasium basketball court is packed with dancers, while a hot band belts out the latest tunes. (There are holds on the differentiated faces of each musician, giving the impression that these are caricatures of those at the studio – but no source seems to identify who is who. Anyone who can peg whose faces appear is invited to contribute.) Plus there is a guest artist – a smooth crooner who weeps into an oversized handkerchief which he wrings out like a towel, in a plaintive ballad entitled “Sob”. He is a parody of singer Johnnie Ray, who had scored a million seller with a similar piece entitled “Cry” for Columbia, and also reputedly shed tears on stage. Winnie is sent by his singing, but Woody declares him to be from nowhere. Woody and Winnie remove their shoes, tossing them on a mountainous pile of student footwear in the corner, and commence some high-stepping dancing. Enter Buzz, looking for revenge. He begins by stuffing a basketball down the back of Woody’s pants, then dribbling him down the coart, tossing him through the hoop above, then laying the points of a spiked shoe where he will land, causing the ball to flatulently deflate. Woody counters by grabbing an armful of Indian clubs, tossing them high into the air, then verbally challenging Buzz to advance and put up his dukes. As Buzz steps forward to clobber Woody, the falling pins clobber him. Buzz picks up a baseball bat and charges Woody. Woody leaps on a bicycle to make a getaway, but finds he is only pedaling a stationary exercise bike. He leaps off the seat just in time to avoid Buzz’s blow, and the seat spring bounces the bat blow back in Buzz’s face. Buzz tries for a fist sock at Woody, but Woody dons a baseball catcher’s mask, causing Buzz’s fist to smack cold steel.