Fine manners, rise in social position, swing, jive, and WWII all conspire to provide adjustment obstacles for our favorite cartoon heroes and some one-shot characters in this week’s survey, covering the end of the 1930’s and the beginnings of the 1940’s. Popeye remains the principal perplexed character of the period, wrapped-up in three new awkward situations, while Tom and Jerry attempt to steal the show, with one of the most fad-driven episodes of the subject years, that might take a little explaining to younger viewers unfamiliar with social history.

It’s the Natural Thing To Do (Paramount, Popeye, 7/30/39 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Tom Johnson, Lod Rossner, anim.) – Once again, Popeye finds himself in a social situation to which his normal personality is entirely unsuited. But this time, Bluto and Olive are right alongside him, in it up to their necks. Popeye and Bluto are having an average day, battling each other in Olive’s yard and spraying logs from Olive’s woodpile in every direction, including through her kitchen window. Olive, completely used to this sort of thing, ducks periodically while washing the dishes, calling out the window, “Have a good time, but keep off of my flowers.” A messenger appears to deliver a telegram to Olive, and for his tip, the messenger receives a clunk on the head from one of the incoming logs at the window. Olive reads the telegram, then quickly rushes out the window to alert the boys of the news. The message is from the Popeye Fan Club, addressed to all of them. “We like your pictures but wish you would cut out the rough stuff once in a while and act more refined – Be ladies and gentlemen – That’s the natural thing to do.” After the signature, the message concludes, “P.S. Now go on with the picture.” Bluto is the first to react. “Gentlemen, eh? Must be a character part.” Popeye chimes in: “I can act rough, but what’s ruff-fined?” Olive insists she’ll take care of everything, and tells the boys to come back later – as gentlemen. Bluto and Popeye return that afternoon, decked out in tuxedos, tails, and top hats. Bluto graciously dusts off the doorbell button with a handkerchief before Popeye rings it. Olive awaits inside, gussied up in fashionable attire with oversized bracelets and earrings. She offers her two suitors a hand apiece to kiss, and they all minuet their way over to the easy chair and sofa to be seated. However, none of them are sure what to do next, and Popeye begins to nervously tug at his stiff collar, complaining how hot it is. Olive consults her book of etiquette for the next move, making special note of a random rule to never dunk your donuts beyond the elbow.

It’s the Natural Thing To Do (Paramount, Popeye, 7/30/39 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Tom Johnson, Lod Rossner, anim.) – Once again, Popeye finds himself in a social situation to which his normal personality is entirely unsuited. But this time, Bluto and Olive are right alongside him, in it up to their necks. Popeye and Bluto are having an average day, battling each other in Olive’s yard and spraying logs from Olive’s woodpile in every direction, including through her kitchen window. Olive, completely used to this sort of thing, ducks periodically while washing the dishes, calling out the window, “Have a good time, but keep off of my flowers.” A messenger appears to deliver a telegram to Olive, and for his tip, the messenger receives a clunk on the head from one of the incoming logs at the window. Olive reads the telegram, then quickly rushes out the window to alert the boys of the news. The message is from the Popeye Fan Club, addressed to all of them. “We like your pictures but wish you would cut out the rough stuff once in a while and act more refined – Be ladies and gentlemen – That’s the natural thing to do.” After the signature, the message concludes, “P.S. Now go on with the picture.” Bluto is the first to react. “Gentlemen, eh? Must be a character part.” Popeye chimes in: “I can act rough, but what’s ruff-fined?” Olive insists she’ll take care of everything, and tells the boys to come back later – as gentlemen. Bluto and Popeye return that afternoon, decked out in tuxedos, tails, and top hats. Bluto graciously dusts off the doorbell button with a handkerchief before Popeye rings it. Olive awaits inside, gussied up in fashionable attire with oversized bracelets and earrings. She offers her two suitors a hand apiece to kiss, and they all minuet their way over to the easy chair and sofa to be seated. However, none of them are sure what to do next, and Popeye begins to nervously tug at his stiff collar, complaining how hot it is. Olive consults her book of etiquette for the next move, making special note of a random rule to never dunk your donuts beyond the elbow.

Finally ready to proceed, Olive clangs a small table gong, signaling a hired maid to wheel in on a bicycle three tall stacks of teacups, plates, sandwiches and pastries. Popeye, Olive, and Bluto spend several frustrating moments attempting to balance the various courses of their repast atop their hands and laps, barely managing to partake of any of the beverages and goodies seated thereon. The tea is too hot for Popeye, producing steam out of his ears. Olive drops a donut on her skirt, but attempts to recover by flipping the donut upwards with a quick parting of her legs. The donut, however, flips onto her nose, a ringer in any horseshoe match. Popeye gets his finger stuck in a teacup handle, and when he pulls it loose, jabs Bluto, who spits out the cream from a filled cruller into Olive’s face. Bluto attempts an apology with unnaturally-long words, but Olive politely dismisses the incident, changing the subject to “Shall we converse a bit?” Bluto remarks that he’s heard that conversing is coming back, and Popeye claims it breaks up the monopoly of not talking. “Who will open?”, Olive asks. In the manner of a poker game, Bluto responds, “I’ll pass.” “They say language is used more for talkin’ than any other”, begins Popeye.

Time passes slowly – so slow, the minute hand of the clock has to develop arms to drag the hour hand past the next hour mark. All of our participants still sit where they were, entirely listless, drooping, and without a thing to say. Popeye finally begins to chuckle to himself, then to laugh heartily, muttering how silly this gentleman stuff is. Bluto begins to join in the laughter, and soon Olive is tittering. She pulls out her etiquette book again, and remarks between giggles, “Etiquette – what a joke!”, tearing the book in two. Popeye continues to belly laugh, and in his reactive movements, accidentally lands a light blow to Bluto’s jaw. Bluto returns the favor, with a laughing jab at Popeye’s face. Soon, the two are jutting out their chins to take the inevitable next blow, and Bluto finally smacks Popeye with a good one, sailing him across the room and through a framed picture, from which his feet appear, twitching in a manner resembling a Russian dancer. Soon, the boys are tossing furniture at each other. Bluto spins Popeye around on a piano stool, while Popeye delivers a mule kick to Bluto’s rear. Olive begins happily playing a flute in appreciation of the action. Popeye dodges Bluto’s throws of crockery, ducking in and out of a chest of drawers, while Olive cracks various vases off of Popeye’s head with a cane. Finally, Bluto spots Popeye’s spinach can upon a table, and decides to fully liven up the action, tossing it willingly to the sailor. Popeye and Bluto now really have at it, rolling through the living room like a steamroller, smashing furniture and tableware in their wake, and sweeping up Olive into their fight cloud as well. The fight continues through the final shot, as Olive, Bluto, and Popeye each pop out of the fight cloud momentarily, to take portions of the final song phrase: “Can’t you see”, “It’s the natural” “Thing to do!”

Time passes slowly – so slow, the minute hand of the clock has to develop arms to drag the hour hand past the next hour mark. All of our participants still sit where they were, entirely listless, drooping, and without a thing to say. Popeye finally begins to chuckle to himself, then to laugh heartily, muttering how silly this gentleman stuff is. Bluto begins to join in the laughter, and soon Olive is tittering. She pulls out her etiquette book again, and remarks between giggles, “Etiquette – what a joke!”, tearing the book in two. Popeye continues to belly laugh, and in his reactive movements, accidentally lands a light blow to Bluto’s jaw. Bluto returns the favor, with a laughing jab at Popeye’s face. Soon, the two are jutting out their chins to take the inevitable next blow, and Bluto finally smacks Popeye with a good one, sailing him across the room and through a framed picture, from which his feet appear, twitching in a manner resembling a Russian dancer. Soon, the boys are tossing furniture at each other. Bluto spins Popeye around on a piano stool, while Popeye delivers a mule kick to Bluto’s rear. Olive begins happily playing a flute in appreciation of the action. Popeye dodges Bluto’s throws of crockery, ducking in and out of a chest of drawers, while Olive cracks various vases off of Popeye’s head with a cane. Finally, Bluto spots Popeye’s spinach can upon a table, and decides to fully liven up the action, tossing it willingly to the sailor. Popeye and Bluto now really have at it, rolling through the living room like a steamroller, smashing furniture and tableware in their wake, and sweeping up Olive into their fight cloud as well. The fight continues through the final shot, as Olive, Bluto, and Popeye each pop out of the fight cloud momentarily, to take portions of the final song phrase: “Can’t you see”, “It’s the natural” “Thing to do!”

• Watch “It’s the Natural Thing To Do” on DailyMotion.

Lucky Pigs (Screen Gems/Columbia, Color Rhapsody. 5/26/39 – Ben Harrison, dir.) – In a tumble-down shack on the wrong side of the tracks live three pigs – an overworked mama pig, dressed in shabby rags, a shiftless papa (Peter Pig) who snores away each day, and Junior, a small pig in sweater too large for him, who spends his afternoons lounging in an ash can. Peter receives a chastising from Mama for squandering what little money the family has upon an Irish Sweepstakes ticket. However, a knock on the door brings unexpected news. Peter’s ticket has won/ Two large satchels of gold coins are deposited in the living room by the courier. At first, it doesn’t sink in. Mama goes back to her washing, and Papa barely budges an eyelid. Suddenly, reality strikes, and Mama and Peter leap simultaneously for the satchels, wrestling and jawing between themselves “It’s mine!” When the dust clears, it seems the tussle has reached a resolution, which each of them holding one satchel. But Mama uses hers as a weapon to clobber Peter, and takes both for herself. The only thing that breaks up the battle is another knock on the door, as the pig family is asked to pose outside with their winnings for the newsreels.

Lucky Pigs (Screen Gems/Columbia, Color Rhapsody. 5/26/39 – Ben Harrison, dir.) – In a tumble-down shack on the wrong side of the tracks live three pigs – an overworked mama pig, dressed in shabby rags, a shiftless papa (Peter Pig) who snores away each day, and Junior, a small pig in sweater too large for him, who spends his afternoons lounging in an ash can. Peter receives a chastising from Mama for squandering what little money the family has upon an Irish Sweepstakes ticket. However, a knock on the door brings unexpected news. Peter’s ticket has won/ Two large satchels of gold coins are deposited in the living room by the courier. At first, it doesn’t sink in. Mama goes back to her washing, and Papa barely budges an eyelid. Suddenly, reality strikes, and Mama and Peter leap simultaneously for the satchels, wrestling and jawing between themselves “It’s mine!” When the dust clears, it seems the tussle has reached a resolution, which each of them holding one satchel. But Mama uses hers as a weapon to clobber Peter, and takes both for herself. The only thing that breaks up the battle is another knock on the door, as the pig family is asked to pose outside with their winnings for the newsreels.

The pigs, dressed as they are, arrive at the swankiest clothiers in town. The proprietor is shocked to find them peering in the door at a high-class fashion show, and tries to get rid of them. “Shoo, shoo! The bargain basement is downstairs!” But the pigs stand their ground and enter, Mama setting down the satchels to try on one of the shop’s creations while still on the mannequin. One of the coins rolls out of a satchel, past the eyes of the proprietor, and his eyes pop, realizing they are loaded. With a clap of his hands, a squad of attendants ushers Mama into a side room for a complete makeover, including a large girdle that gives her portly belly an instant slim waistline. The proprietor dips his arms deep into the satchels’ wealth, and it is clear he intends to see that this money is spent – well. Within a few moments, the proprietor emerges on the street, carrying the satchels to a new private limousine. Mama, Papa, and Junior also emerge, in new threads and flashy jewelry, strutting their stuff in slow and deliberate fashion to set themselves apart from the low-brows. Off the limousine whisks them to their new mansion, the interior of which the pigs give their nodding approval of. The shop proprietor, now turned their financial advisor, announces that everything will be put in readiness for their social debut tomorrow.

However, the news story of Peter’s good luck has not gone unnoticed – by the I.R.S. (merely referred to here as the “Tax Collector”). With the sounding of a bugle, a brigade of little men in surreptitious-looking investigator’s outfits is assembled for a parade across town to the mansion. Each one marching is armed with a vacuum cleaner, while others drive command tanks with multiple gun-style barrels, upon the end of each appearing a blinking, snooping electric eye. They quickly converge upon the mansion, where a gala party is in progress for all the lords and ladies capable of receiving invitations. As the tax men enter, the guests depart – but quick. The pigs are taken by surprise, as several tanks hook up tow chains to the entire house, and haul away, leaving left standing on the lot only the brickwork of the fireplace and the front doot. Another tax man gets to use his vacuum, sucking the gown and jewelry off Mama and the top hat, tails and trousers off Peter – as well as what is left of the satchels of money from the pigs’ advisor, who thereafter runs away in panic. The pigs are left weeping, until Junior, who apparently was out somewhere during the melee, arrives at the door. Seeing his parents’ plight, he reaches into his pocket, producing a piggy bank, which still jingles with coin. Papa and Mama revert to their wrestling moves, in another mad scramble to get hold of the small nest egg. But, there is another knock at the door – this time, by a talking horse. Confirming that this is the residence of Peter Pig, the horse announces that he was the winner of the race in the Irish Sweepstakes – and the piggy bank’s contents will just cover his share of the winnings! Iris out, leaving the pigs back in abject poverty again.

However, the news story of Peter’s good luck has not gone unnoticed – by the I.R.S. (merely referred to here as the “Tax Collector”). With the sounding of a bugle, a brigade of little men in surreptitious-looking investigator’s outfits is assembled for a parade across town to the mansion. Each one marching is armed with a vacuum cleaner, while others drive command tanks with multiple gun-style barrels, upon the end of each appearing a blinking, snooping electric eye. They quickly converge upon the mansion, where a gala party is in progress for all the lords and ladies capable of receiving invitations. As the tax men enter, the guests depart – but quick. The pigs are taken by surprise, as several tanks hook up tow chains to the entire house, and haul away, leaving left standing on the lot only the brickwork of the fireplace and the front doot. Another tax man gets to use his vacuum, sucking the gown and jewelry off Mama and the top hat, tails and trousers off Peter – as well as what is left of the satchels of money from the pigs’ advisor, who thereafter runs away in panic. The pigs are left weeping, until Junior, who apparently was out somewhere during the melee, arrives at the door. Seeing his parents’ plight, he reaches into his pocket, producing a piggy bank, which still jingles with coin. Papa and Mama revert to their wrestling moves, in another mad scramble to get hold of the small nest egg. But, there is another knock at the door – this time, by a talking horse. Confirming that this is the residence of Peter Pig, the horse announces that he was the winner of the race in the Irish Sweepstakes – and the piggy bank’s contents will just cover his share of the winnings! Iris out, leaving the pigs back in abject poverty again.

Millionaire Hobo (Screen Gems/Columbia, Phantasy (Scrappy), 11/24/39 – Allen Rose, story (dir.?)), follows in a similar vein to Lucky Pigs, but drives the “rags to riches” story into the ground. This time, a disheveled hobo plods along the road, in time to the fitting musical underscore of Hoagy Carmichael’s composition, “Lazybones”. He spends his idle time complaining about how others get the breaks, while he has all the brains. Facial animation is utterly strange, as his manner of speech is much like a mutter to himself – so the animator seems to only half-animate his uttered words, sometimes skipping entire syllables without moving his lips, and at other times merely twisting the lips as if to form a word, but not quite reaching it. The hobo asserts he’s working too hard (doing nothing), and falls asleep under a tree, deciding to wait until his ship comes in. Enter Scrappy (in what amounts to only a cameo) as a messenger boy on motorcycle. He delivers a telegram to the hobo (though, having no place of residence, it is a positive miracle that Scrappy ever found him). The news reads that an uncle Horace has passed on. The hobo continues to read, with his thumb placed over part of one line of the paper. He reads the phrase “left you a million”, not noticing that there is no visible period after the last word. In a delayed reaction, the hobo finally takes this in. “A MILLION!!” In a move that entirely destroys any hope of building up suspense or surprise for a storyline, Scrappy picks up the telegram which has fallen from the hobo’s hand, and reads the additional word which had been covered by the hobo’s thumb, to complete the sentence – “a million cats.” Although the punch line (such as it is) is now entirely spoiled for us (in a manner similar to an early giveaway of surprise plot point by Tex Avery a few seasons later in “Tortoise Beats Hare” – a mistake Avery learned from and never repeated), Scrappy can’t break through the daydreams of the hobo about his new-found “wealth” to get him to listen to the plain English of what the telegram really says. The hobo is too busy imagining himself calling for his chauffeur and limousine, and waddles off down the road to the city without hearing a word Scrappy says (though Scrappy clearly repeats the phrase “a million cats” multiple times, overkilling the point for the viewers).

Millionaire Hobo (Screen Gems/Columbia, Phantasy (Scrappy), 11/24/39 – Allen Rose, story (dir.?)), follows in a similar vein to Lucky Pigs, but drives the “rags to riches” story into the ground. This time, a disheveled hobo plods along the road, in time to the fitting musical underscore of Hoagy Carmichael’s composition, “Lazybones”. He spends his idle time complaining about how others get the breaks, while he has all the brains. Facial animation is utterly strange, as his manner of speech is much like a mutter to himself – so the animator seems to only half-animate his uttered words, sometimes skipping entire syllables without moving his lips, and at other times merely twisting the lips as if to form a word, but not quite reaching it. The hobo asserts he’s working too hard (doing nothing), and falls asleep under a tree, deciding to wait until his ship comes in. Enter Scrappy (in what amounts to only a cameo) as a messenger boy on motorcycle. He delivers a telegram to the hobo (though, having no place of residence, it is a positive miracle that Scrappy ever found him). The news reads that an uncle Horace has passed on. The hobo continues to read, with his thumb placed over part of one line of the paper. He reads the phrase “left you a million”, not noticing that there is no visible period after the last word. In a delayed reaction, the hobo finally takes this in. “A MILLION!!” In a move that entirely destroys any hope of building up suspense or surprise for a storyline, Scrappy picks up the telegram which has fallen from the hobo’s hand, and reads the additional word which had been covered by the hobo’s thumb, to complete the sentence – “a million cats.” Although the punch line (such as it is) is now entirely spoiled for us (in a manner similar to an early giveaway of surprise plot point by Tex Avery a few seasons later in “Tortoise Beats Hare” – a mistake Avery learned from and never repeated), Scrappy can’t break through the daydreams of the hobo about his new-found “wealth” to get him to listen to the plain English of what the telegram really says. The hobo is too busy imagining himself calling for his chauffeur and limousine, and waddles off down the road to the city without hearing a word Scrappy says (though Scrappy clearly repeats the phrase “a million cats” multiple times, overkilling the point for the viewers).

Interminable time is wasted on an extended visit to the barber shop for a facial makeover (a sequence which could have been accomplished in a few short shots had there been other plot material to go around, but which instead is padded with every possible facial nuance and gesture to drag the bit out as long as possible, while failing to accomplish laughs). Then, in slightly quicker manner, the hobo acquires a custom-tailored wardrobe on credit, charges the bill for a limousine, buys a mansion, a yacht, a skyscraper, a plane, and even the Brooklyn Bridge, and tells everyone to send him the bill. He finally shows up at the lawyer’s office for his inheritance, and the lawyer opens a crate to cover him in the emerging felines. The hobo finally looks again at the telegram, sees the word “cats”, and remarks, “I knew there’d be a catch to it.” What next? Do we see the creditors come with bills in hand? A mad chase? Another ray of hope for good fortune, or a working off of the debt, perhaps behind bars? No. The hobo merely goes to sleep again in the lawyer’s office, presumably to wait for his next ship to come in. For this, we waited five minutes? If you have better use of your time, don’t bother waiting.

Interminable time is wasted on an extended visit to the barber shop for a facial makeover (a sequence which could have been accomplished in a few short shots had there been other plot material to go around, but which instead is padded with every possible facial nuance and gesture to drag the bit out as long as possible, while failing to accomplish laughs). Then, in slightly quicker manner, the hobo acquires a custom-tailored wardrobe on credit, charges the bill for a limousine, buys a mansion, a yacht, a skyscraper, a plane, and even the Brooklyn Bridge, and tells everyone to send him the bill. He finally shows up at the lawyer’s office for his inheritance, and the lawyer opens a crate to cover him in the emerging felines. The hobo finally looks again at the telegram, sees the word “cats”, and remarks, “I knew there’d be a catch to it.” What next? Do we see the creditors come with bills in hand? A mad chase? Another ray of hope for good fortune, or a working off of the debt, perhaps behind bars? No. The hobo merely goes to sleep again in the lawyer’s office, presumably to wait for his next ship to come in. For this, we waited five minutes? If you have better use of your time, don’t bother waiting.

Commencing in 1941, Walter Lantz launched into a series of color cartoons capitalizing upon the growing popularity of swing bands. During that year, the episodes had no official series banner. Disney had ended the run of Silly Symphonies a few seasons before, so Lantz felt it fair game to ultimately choose a series title which would come dangerously close to the Disney original – Swing Symphonies. A recurring theme of these films was adapting to the new trends and rhythms of the period, incorporating such beats and melodies into various ways of life or setting situations. Big band beats would liven up a ghost town (Boogie Woogie Man), a Western ranch (Cow Cow Boogie), an Indian reservation and rainmaking ceremony (Boogie Woogie Sioux), and even a tribe in the Sandwich Islands (Jungle Jive). For our trail’s present purposes, we’ll look at the first two, which for reasons of political incorrectness, never made the ranks of television distribution.

Scrub Me Mama with a Boogie Beat (Lantz, Universal, 3/28/41 – Walter Lantz, dir.), takes us to a setting that needs a bringing up-to-date worse than Betty Boop’s Hillbillyville – the riverfront hamlet of Lazy Town. Unlike most points of civilization in the deep South, there appear to be no white residents in this community. The entire cast is portrayed in extreme stereotypes of black caricature. Some of these images are quite disturbing, and rank as the most offensive of their time since some of the “Uncle Tom” cartoons of the early Van Beuren days. (My first exposure to this film was in a rare public screening of a 35mm print at UCLA during my student days. Laughter was at times uproarious but decidedly nervous, and I recall remarking to friends at the event, “And for this. Walter Lantz didn’t get lynched?”

Scrub Me Mama with a Boogie Beat (Lantz, Universal, 3/28/41 – Walter Lantz, dir.), takes us to a setting that needs a bringing up-to-date worse than Betty Boop’s Hillbillyville – the riverfront hamlet of Lazy Town. Unlike most points of civilization in the deep South, there appear to be no white residents in this community. The entire cast is portrayed in extreme stereotypes of black caricature. Some of these images are quite disturbing, and rank as the most offensive of their time since some of the “Uncle Tom” cartoons of the early Van Beuren days. (My first exposure to this film was in a rare public screening of a 35mm print at UCLA during my student days. Laughter was at times uproarious but decidedly nervous, and I recall remarking to friends at the event, “And for this. Walter Lantz didn’t get lynched?”

The citizens of Lazy Town – at least the male ones – might all be compared in some ways to a society of Stepin Fetchits – every one of them shiftless, speaking in ultra-slow drawl, and at all times half-asleep. One’s reaction to a mosquito sting is as slow as the speech of the sloth in “Zootopia”, ultimately resulting in a half-hearted “Ouch” that sounds as if the speaker wondered if it was seriously worth the effort to say. A “fight” between two citizens (which half-opens the eyes of others) consists of two rivals slapping each other’s faces in what looks like the magic of the slow-motion camera, punctuated at intervals with yawning moans of “You take that,” Lifting an idea from Tex Avery’s hillbilly cartoons, the laid-back mood even rubs off on the local dogs and cats, who will barely exert the effort to bark or spit at each other.

Amidst this throng is a tubby washerwoman at the Lazy Town hand laundry. She seems to be the most energetic and industrious the city has – though her moves of clothes up and down a washboard are still slow and belabored. Enter the element that will change everything – a steamboat docking at the Lazy Town lading for a one-hour stop for lunch, and a female passenger. Unlike anyone else we’ve yet seen in the town (though a few similar local girls show up from nowhere later in a twice-repeated shot), she is not drawn as a stereotype Instead, she appears in realistic – perhaps idealized – proportion, with curves in all the right places, a shifting gait that struts to really show off the goods, classy clothes, and a face and complexion which are remarkably lighter in skin tone than anyone else – suggesting and no doubt inspired by MGM star Lena Horne, who would appear within the next few years in some of her most celebrated roles (MGM’s “Cabin In the Sky”, and in loan-out to Fox for “Stormy Weather”). Just strutting down the gangplank makes many of the locals raise their heads and exert the effort to spread broad smiles across their faces. Even the two “fighters” pick up the pace. The girl stops by the fence of the washerwoman, and remarks. “That ain’t no way to wash clothes. What you need is rhythm.” The washerwoman doesn’t get it, and the girl volunteers to show what she means. Breaking into song, she describes how Harlem washerwomen scrub their clothes with a boogie beat – to the lyrics of the title song, a piece which had received recent recorded popularity under the bandleading of Will Bradley, and in a vocal performance by the Andrews Sisters. The rhythm seems to be all that is needed to fully awaken the town, who throng to parade behind the girl, accompany her on musical instruments, and pick up the pace in general on everything they do. Like Boop’s hillbillies, they are all brought up to date, and as the boat pulls out, the girl waves goodbye from the deck to the cheering crowd on the docks, and to the washerwoman, who now moves her frame with vigor, and bends over, to reveal “The End” embroidered upon her oversized undergarments.

Amidst this throng is a tubby washerwoman at the Lazy Town hand laundry. She seems to be the most energetic and industrious the city has – though her moves of clothes up and down a washboard are still slow and belabored. Enter the element that will change everything – a steamboat docking at the Lazy Town lading for a one-hour stop for lunch, and a female passenger. Unlike anyone else we’ve yet seen in the town (though a few similar local girls show up from nowhere later in a twice-repeated shot), she is not drawn as a stereotype Instead, she appears in realistic – perhaps idealized – proportion, with curves in all the right places, a shifting gait that struts to really show off the goods, classy clothes, and a face and complexion which are remarkably lighter in skin tone than anyone else – suggesting and no doubt inspired by MGM star Lena Horne, who would appear within the next few years in some of her most celebrated roles (MGM’s “Cabin In the Sky”, and in loan-out to Fox for “Stormy Weather”). Just strutting down the gangplank makes many of the locals raise their heads and exert the effort to spread broad smiles across their faces. Even the two “fighters” pick up the pace. The girl stops by the fence of the washerwoman, and remarks. “That ain’t no way to wash clothes. What you need is rhythm.” The washerwoman doesn’t get it, and the girl volunteers to show what she means. Breaking into song, she describes how Harlem washerwomen scrub their clothes with a boogie beat – to the lyrics of the title song, a piece which had received recent recorded popularity under the bandleading of Will Bradley, and in a vocal performance by the Andrews Sisters. The rhythm seems to be all that is needed to fully awaken the town, who throng to parade behind the girl, accompany her on musical instruments, and pick up the pace in general on everything they do. Like Boop’s hillbillies, they are all brought up to date, and as the boat pulls out, the girl waves goodbye from the deck to the cheering crowd on the docks, and to the washerwoman, who now moves her frame with vigor, and bends over, to reveal “The End” embroidered upon her oversized undergarments.

The saving grace of this cartoon, one of the few that, for obvious reasons, was not renewed for copyright and fell into the public domain, is Darryl Calker’s infectious jazz score, which injects life into the production and seemingly even into the drawings of the animators. I am quite surprised after all these years that no upload has turned up on the internet of a Universal 12″ acetate disc, pressed in multiple copies at the time of the film’s release, featuring the entire score and vocal without dialogue or sound effects. It’s a wonderful way to hear the full effect of the music without the distracting visuals, and there must be further copies out there that someone could share, as I’ve seen the actual record on multiple occasions, and own one myself which unfortunately is rather lost within piles of old storage boxes. Anyone out there able to transfer and share with the world their copy?

The Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy of Company B (Lantz/Universal, 9/1/41 – Walter Lantz, dir.), follows in a similar vein, again featuring an all-black cast that is only slightly-less stereotyped than its predecessor. Its central character faces a sort of culture-shock in reverse. Instead of beginning as a simple, unskilled, and out-of-step fellow, trumpeter Hot-Breath Harry (the Harlem Heatwave) is at the top of his game, paying top night spots, and totally in the groove to please his audiences. However, he becomes out-of-place when his number cones up with the local draft board, and, despite his fame and his claims of having influence to avoid the service, he suddenly finds himself in khaki, deposited in the all-negro infantry regiment of Company B, and ordered to perform service as the Company’s bugler. Harry is quite taken aback just at being directed to perform on a brass instrument that has no valves, thus incapable of uttering even a complete musical scale. Worse yet, Company B seems to be inhabited by the roughest, toughest of soldiers, who don’t take well to being roused from their slumber at an unearthly early hour of the morning by any bugler’s music. Each of them seems to pack weapons such as meat cleavers, daggers, bats, and black jacks. Even an attempt to practice in advance of morning gets Harry beaned on the back of the head with a spiked army boot.

The Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy of Company B (Lantz/Universal, 9/1/41 – Walter Lantz, dir.), follows in a similar vein, again featuring an all-black cast that is only slightly-less stereotyped than its predecessor. Its central character faces a sort of culture-shock in reverse. Instead of beginning as a simple, unskilled, and out-of-step fellow, trumpeter Hot-Breath Harry (the Harlem Heatwave) is at the top of his game, paying top night spots, and totally in the groove to please his audiences. However, he becomes out-of-place when his number cones up with the local draft board, and, despite his fame and his claims of having influence to avoid the service, he suddenly finds himself in khaki, deposited in the all-negro infantry regiment of Company B, and ordered to perform service as the Company’s bugler. Harry is quite taken aback just at being directed to perform on a brass instrument that has no valves, thus incapable of uttering even a complete musical scale. Worse yet, Company B seems to be inhabited by the roughest, toughest of soldiers, who don’t take well to being roused from their slumber at an unearthly early hour of the morning by any bugler’s music. Each of them seems to pack weapons such as meat cleavers, daggers, bats, and black jacks. Even an attempt to practice in advance of morning gets Harry beaned on the back of the head with a spiked army boot.

When 5:00 a.m. arrives, Harry’s knees are knocking. Anticipating what might happen, he bids the audience, “so long”, and raises the bugle to his lips. A few notes, and the meat cleaver comes flying through the barracks’ wall/ slicing the bell of the bugle in two down the middle. The sergeant approaches Harry, demanding, “Do we get Reveille, or do you get Taps?” Harry backs up to a shelf in the barracks – and discovers to his delight that Uncle Sam, in delivering him to his assigned regiment, did not entirely deprive him of his belongings – and his old faithful trumpet gleams brightly from the shelf. Breaking with tradition, Harry grabs the instrument, and decides to show the army how this musical piece should be presented – in his own style, with notes between the notes. The camp awakens, eyes in the darkness opening in wonderment at the new and modern sounds. As lights go on, so do broad smiles on every recruit’s face. Presenting the Andrews Sisters’ musical hit from Universal’s “Private Buckaroo”, the remainder of the film is another production number, with the soldiers performing with vim and energy through their morning routine and daily training. All end the day equally happy, as Harry lulls them to sleep with his own boogie rhythms instead of Taps, seen silhouetted against the moon for the fade out. Another hot musical score by Darryl Calker, and nominated for an Academy Award.

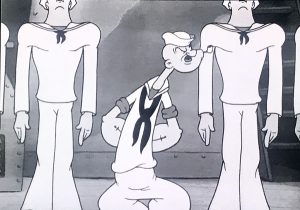

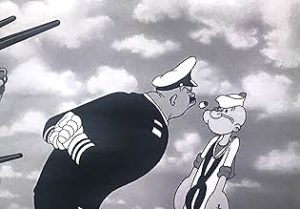

The Mighty Navy (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 11/14/41 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Abner Matthews, anim.) – Popeye once again is placed in unfamiliar waters – this time, thanks to Uncle Sam. One might wonder at the selectivity of the selective service, given Popeye’s usual age specification as somewhere around 40, but in fact, wartime conditions allowed for inductions of men at least up to age 45. Anyway, Popeye’s number is up, and he finds himself in navy white for the first time as opposed to his old mariner’s outfit as seen in the comics. At morning roll call, Popeye stands out like a sore thumb – the shortest of the young recruits, with the scrawniest build, and curiously peering around the ship, trying to figure out where the sails are at. The captain can’t believe his eyes, and picks up Popeye as if he was inspecting a rifle, looking straight down his throat as if checking the cleanliness of the barrel of a gun. “So, you want to be a sailor”, he states condescendingly. Popeye is insulted. “I yam a sailor. I was born a sailor, an’ there’s nothin’ what I doesn’t know about a ship because I’m Popeye the sailor man (toot toot)!” The captain puts his knowledge to the test, first with assignment to hoist anchor. Ignoring a control panel for motorized hauling-in, Popeye takes hold of the anchor chain with his mighty muscles, and begins tugging the chain aboard bodily. However, the anchor is stuck on a rock on the bottom, and so Popeye drags the entire bow of the ship underwater, drenching the Captain. Popeye’s next test is to aim a battleship gun turret. “Where’s the trigger on this pistol?”, Popeye questions. By the time Popeye is through trying to figure out which button to push and wheel to spin, the three gun barrels are wound together in a braid. Test no. 3 is to see if Popeye can fly a plane off a launching catapult. Popeye observes that the plane is labeled “dive bomber” – and gets the wrong idea. He gets the engine started, taxis to the end of the deck, then bounces and leaps off its edge as if a diving board. The plane rises a short distance, then bends downward, executing a series of dives which Popeye verbally describes: “Jack knife, swan, twist,…and belly flopper”, as the plane sinks into the sea. “Get that man below”, shouts the furious Captain.

The Mighty Navy (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 11/14/41 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Abner Matthews, anim.) – Popeye once again is placed in unfamiliar waters – this time, thanks to Uncle Sam. One might wonder at the selectivity of the selective service, given Popeye’s usual age specification as somewhere around 40, but in fact, wartime conditions allowed for inductions of men at least up to age 45. Anyway, Popeye’s number is up, and he finds himself in navy white for the first time as opposed to his old mariner’s outfit as seen in the comics. At morning roll call, Popeye stands out like a sore thumb – the shortest of the young recruits, with the scrawniest build, and curiously peering around the ship, trying to figure out where the sails are at. The captain can’t believe his eyes, and picks up Popeye as if he was inspecting a rifle, looking straight down his throat as if checking the cleanliness of the barrel of a gun. “So, you want to be a sailor”, he states condescendingly. Popeye is insulted. “I yam a sailor. I was born a sailor, an’ there’s nothin’ what I doesn’t know about a ship because I’m Popeye the sailor man (toot toot)!” The captain puts his knowledge to the test, first with assignment to hoist anchor. Ignoring a control panel for motorized hauling-in, Popeye takes hold of the anchor chain with his mighty muscles, and begins tugging the chain aboard bodily. However, the anchor is stuck on a rock on the bottom, and so Popeye drags the entire bow of the ship underwater, drenching the Captain. Popeye’s next test is to aim a battleship gun turret. “Where’s the trigger on this pistol?”, Popeye questions. By the time Popeye is through trying to figure out which button to push and wheel to spin, the three gun barrels are wound together in a braid. Test no. 3 is to see if Popeye can fly a plane off a launching catapult. Popeye observes that the plane is labeled “dive bomber” – and gets the wrong idea. He gets the engine started, taxis to the end of the deck, then bounces and leaps off its edge as if a diving board. The plane rises a short distance, then bends downward, executing a series of dives which Popeye verbally describes: “Jack knife, swan, twist,…and belly flopper”, as the plane sinks into the sea. “Get that man below”, shouts the furious Captain.

Popeye is assigned the lowest of tasks – peeling onions in the ship’s galley. A series of explosions outside call Popeye’s attention to the porthole, where he spies a fleet of battleships launching broadsides at his ship, one carrying a flag which falls just short of placing the U.S. at official war with anybody, reading “Enemy (Name Your Own).” On deck, a pair of specially skilled gunmen attempt to aim a large gun by the book, calling out coordinates for elevation, azimuth, etc., but taking so long, no shots are being fired. The battleships circle the training ship as if Indians on the warpath, even breaking into tribal war-dance rhythms. As Popeye sticks his head out the porthole, and avoids enemy fire in the manner of a “dodger” dodging baseballs at a carnival, an enemy shell zeroes in on the porthole, causing Popeye to duck back in, open a porthole on the opposite side of the deck, and let the shell out again. “That’s all I can stands, I can’t stands no more”, shouts the sailor. Climbing to the main deck, Popeye spies the gunners still fussing over their mathematics. “Gimme dat peashooter”, yells our hero, yanking the gun from its mounting, and holding it like he was firing a giant pistol. He scores hit after hit on the enemy fleet as if they were ducks in a shooting gallery, toppling each hip over backwards like a flat target. An aircraft carrier launches its entire armada of fighter planes at him. As the planes take off one by one, Popeye follows the etiquette of a skeet shooting match, calling for each target with the call of “Pull”, then blasting each plane from the sky. The carrier skedaddles away with the audible whimpers of a wounded dog. But the enemy has one more weapon up its sleeve – its largest of battleships, towering three times over the others, and filled to the railings with blasting cannon. Popeye knows just how to address the situation. He thrusts himself into a torpedo launcher, eats his can of spinach, revs up his feet like a torpedo propeller, and launches himself directly at the firing ship. Holding his mighty fist out before him, he scores a direct hit on the ship’s bow, reducing the vessel to a bare metal framework, which sinks below the waves.

Popeye is assigned the lowest of tasks – peeling onions in the ship’s galley. A series of explosions outside call Popeye’s attention to the porthole, where he spies a fleet of battleships launching broadsides at his ship, one carrying a flag which falls just short of placing the U.S. at official war with anybody, reading “Enemy (Name Your Own).” On deck, a pair of specially skilled gunmen attempt to aim a large gun by the book, calling out coordinates for elevation, azimuth, etc., but taking so long, no shots are being fired. The battleships circle the training ship as if Indians on the warpath, even breaking into tribal war-dance rhythms. As Popeye sticks his head out the porthole, and avoids enemy fire in the manner of a “dodger” dodging baseballs at a carnival, an enemy shell zeroes in on the porthole, causing Popeye to duck back in, open a porthole on the opposite side of the deck, and let the shell out again. “That’s all I can stands, I can’t stands no more”, shouts the sailor. Climbing to the main deck, Popeye spies the gunners still fussing over their mathematics. “Gimme dat peashooter”, yells our hero, yanking the gun from its mounting, and holding it like he was firing a giant pistol. He scores hit after hit on the enemy fleet as if they were ducks in a shooting gallery, toppling each hip over backwards like a flat target. An aircraft carrier launches its entire armada of fighter planes at him. As the planes take off one by one, Popeye follows the etiquette of a skeet shooting match, calling for each target with the call of “Pull”, then blasting each plane from the sky. The carrier skedaddles away with the audible whimpers of a wounded dog. But the enemy has one more weapon up its sleeve – its largest of battleships, towering three times over the others, and filled to the railings with blasting cannon. Popeye knows just how to address the situation. He thrusts himself into a torpedo launcher, eats his can of spinach, revs up his feet like a torpedo propeller, and launches himself directly at the firing ship. Holding his mighty fist out before him, he scores a direct hit on the ship’s bow, reducing the vessel to a bare metal framework, which sinks below the waves.

The final scene finds Popeye back on board his ship, with an assembly of crew and officers surrounding him, for a presentation. “For your exceptional performance under fire, the Navy is proud to honor you with this reward.” The Captain hands Popeye what looks like a scroll, which Popeye unrolls, revealing an illustration of himself in his old uniform, delivering a sock with his fist. “Me picture in a circle. What’s it for?”, asks the curious sailor. “The official insignia of the Navy’s bomber squadron.” The final scene shows the insignia proudly worn upon a squadron of bombers (they may be of Consolidated B-24 class), sailing through the skies on a mission, as we fade out. (Unfortunately, while this seemed to commemorate a genuine official act of the services of which the Fleischer studios could be proud, it may have only been wishful thinking. Although there are real-life instances where Popeye’s image appeared as insignia for small squadrons or on random nose imagery of bombers or fighters, and even one featuring Poopdeck Pappy. I can find no record on the internet of this insignia ever receiving official use, nor of any Navy bomber squadron associated with it. The very fact that no identifying number of a squadron is referenced in the film may provide confirmation that the award is a fake – something that Little Lulu might have been anxious to point out to Popeye a few years later.)

The final scene finds Popeye back on board his ship, with an assembly of crew and officers surrounding him, for a presentation. “For your exceptional performance under fire, the Navy is proud to honor you with this reward.” The Captain hands Popeye what looks like a scroll, which Popeye unrolls, revealing an illustration of himself in his old uniform, delivering a sock with his fist. “Me picture in a circle. What’s it for?”, asks the curious sailor. “The official insignia of the Navy’s bomber squadron.” The final scene shows the insignia proudly worn upon a squadron of bombers (they may be of Consolidated B-24 class), sailing through the skies on a mission, as we fade out. (Unfortunately, while this seemed to commemorate a genuine official act of the services of which the Fleischer studios could be proud, it may have only been wishful thinking. Although there are real-life instances where Popeye’s image appeared as insignia for small squadrons or on random nose imagery of bombers or fighters, and even one featuring Poopdeck Pappy. I can find no record on the internet of this insignia ever receiving official use, nor of any Navy bomber squadron associated with it. The very fact that no identifying number of a squadron is referenced in the film may provide confirmation that the award is a fake – something that Little Lulu might have been anxious to point out to Popeye a few years later.)

• Watch “Thew Mighty Navy” on DailyMotion.

Pest Pilot (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 8/8/41 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Dave Tendlar/Tom Baron, anim.) – For once, Popeye is NOT the character out of date in this one, but hands off the problems of catching up with the times to someone else – Poopdeck Pappy. The ancient mariner who is Popeye’s father thinks himself full of “vitaliky” and ready to try anything, but is beneath the surface still rooted in his old-fogie ways and hopelessly inept at adapting to new skills and situations. Here, he desires to pursue a new career – joining up with Popeye’s roster of pilots at an “air-conditioned airport” (with a motto sign reading “Airplanes is the safest things on Earth”). When Poopdeck was choosing careers, the airplane no doubt hadn’t even been invented – so Popeye senses that Poopdeck is just not a proper fit for air service. As Popeye hand-whittles a perfect propeller out of a raw board at lightning speed, then bends the propeller shaft with his bare hands into a U-curve to hold it in place, Poopdeck appears at Popeye’s door, imitating the sounds of an aircraft engine. “Ahoy, son”, he asks, “Need a good pilot?” “Nope. Got one”, replies Popeye. Pappy holds up a poster reading “Be a pilot and your income will rise sky high”, and pokes his head through the paper in place of the pilot’s face depicted. “I’m just the type”, he insists. Popeye responds, “You’re not quite young enough yet to fly – but you’re old enough to read!” He points to another poster on the wall: “All prospective pilots must be young, strong, and healthy, see well, and look good.” “That’s me all over”, boasts Pappy, pulling up his shirt, to briefly expand his rickety chest, which looks like the torso of the nursery-rhyme “crooked man”. Popeye delivers a strike three to Pappy’s arguments – “Ya don’t know how ta fly.” Pappy states he does so, and can prove it. He produces two photos from his wallet. One depicts him at grade school age, with caption, “Little Poopdeck, kite flying champion of Public School No. 61?, while the second shows him in a photography studio behind a fake backdrop of a cardboard plane, captioned, “Greetings from Coney Island”.

Pest Pilot (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 8/8/41 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Dave Tendlar/Tom Baron, anim.) – For once, Popeye is NOT the character out of date in this one, but hands off the problems of catching up with the times to someone else – Poopdeck Pappy. The ancient mariner who is Popeye’s father thinks himself full of “vitaliky” and ready to try anything, but is beneath the surface still rooted in his old-fogie ways and hopelessly inept at adapting to new skills and situations. Here, he desires to pursue a new career – joining up with Popeye’s roster of pilots at an “air-conditioned airport” (with a motto sign reading “Airplanes is the safest things on Earth”). When Poopdeck was choosing careers, the airplane no doubt hadn’t even been invented – so Popeye senses that Poopdeck is just not a proper fit for air service. As Popeye hand-whittles a perfect propeller out of a raw board at lightning speed, then bends the propeller shaft with his bare hands into a U-curve to hold it in place, Poopdeck appears at Popeye’s door, imitating the sounds of an aircraft engine. “Ahoy, son”, he asks, “Need a good pilot?” “Nope. Got one”, replies Popeye. Pappy holds up a poster reading “Be a pilot and your income will rise sky high”, and pokes his head through the paper in place of the pilot’s face depicted. “I’m just the type”, he insists. Popeye responds, “You’re not quite young enough yet to fly – but you’re old enough to read!” He points to another poster on the wall: “All prospective pilots must be young, strong, and healthy, see well, and look good.” “That’s me all over”, boasts Pappy, pulling up his shirt, to briefly expand his rickety chest, which looks like the torso of the nursery-rhyme “crooked man”. Popeye delivers a strike three to Pappy’s arguments – “Ya don’t know how ta fly.” Pappy states he does so, and can prove it. He produces two photos from his wallet. One depicts him at grade school age, with caption, “Little Poopdeck, kite flying champion of Public School No. 61?, while the second shows him in a photography studio behind a fake backdrop of a cardboard plane, captioned, “Greetings from Coney Island”.

Popeye laughs heartily, and calls Pappy nothing but a “picture postcard pilot”. Pappy keeps insisting that Popeye “give this old barnacle-scrapin’ seadog a chance”, but Popeye gets tough, threatening “I’ll make ‘ya FLY!” He lunges at Pappy, causing him to retreat out the hangar door, while Popeye nails up signs reading “Scram”, “Go home”, “Beat it”, “No trespassing”, “This means you”, etc. “I can take a hint”, mutters Pappy. But outside rests a plane which is unattended. Pappy, seeing opportunity to prove he has the stuff, tries to spin the prop, bur can’t get the engine to kick over. About to give up, he gives the propeller blade a backwards kick before departing. The kick is a lucky blow, and the plane starts up. Pappy jumps into the cockpit, looks around until he finds the control stick, pulls back, and is away. He ascends in a zoom past a house, so fast that the force of his passing rips away the walls, reducing the structure to its wooden framework. He zips through a cloud, leaving a watery hole of his silhouette. A dissolve transports us to another location, where passengers stampede as a mob out the exit of an underground subway, followed by Pappy and his plane in pursuit. Another dissolve finds us at a tropical island, where Pappy’s plane skims over the tops of palm trees, giving their fronds a “butch”: haircut. Another dissolve, and we are at the Arctic, where the exhaust of the passing plane melts two Eskimos out of their igloo house and home. Yet another dissolve, and we are back at Popeye’s airport, with the plane performing wild loops just outside the hangar, then heading straight up, with Poopdeck hanging from the tail. Pappy looks down, and sees the entire planet falling farther and farther away. He struggles to climb up the length of the fuselage, and just reaches the control stick, forcing it forward. Now the plane reverses course, heading straight down, and tossing Pappy into the cockpit. The view of the Earth is reversed, looming closer and closer. Pappy seeks in vain any control or lever on the dashboard that might help him, and opens a hatch with a telephone inside. Pappy speaks frantically into the receiver: “Hello! Hello! How d’ya anchor this doggone sloop?” A telephone operator replies, “Sorry, sir. We can’t give you that information.”

Popeye laughs heartily, and calls Pappy nothing but a “picture postcard pilot”. Pappy keeps insisting that Popeye “give this old barnacle-scrapin’ seadog a chance”, but Popeye gets tough, threatening “I’ll make ‘ya FLY!” He lunges at Pappy, causing him to retreat out the hangar door, while Popeye nails up signs reading “Scram”, “Go home”, “Beat it”, “No trespassing”, “This means you”, etc. “I can take a hint”, mutters Pappy. But outside rests a plane which is unattended. Pappy, seeing opportunity to prove he has the stuff, tries to spin the prop, bur can’t get the engine to kick over. About to give up, he gives the propeller blade a backwards kick before departing. The kick is a lucky blow, and the plane starts up. Pappy jumps into the cockpit, looks around until he finds the control stick, pulls back, and is away. He ascends in a zoom past a house, so fast that the force of his passing rips away the walls, reducing the structure to its wooden framework. He zips through a cloud, leaving a watery hole of his silhouette. A dissolve transports us to another location, where passengers stampede as a mob out the exit of an underground subway, followed by Pappy and his plane in pursuit. Another dissolve finds us at a tropical island, where Pappy’s plane skims over the tops of palm trees, giving their fronds a “butch”: haircut. Another dissolve, and we are at the Arctic, where the exhaust of the passing plane melts two Eskimos out of their igloo house and home. Yet another dissolve, and we are back at Popeye’s airport, with the plane performing wild loops just outside the hangar, then heading straight up, with Poopdeck hanging from the tail. Pappy looks down, and sees the entire planet falling farther and farther away. He struggles to climb up the length of the fuselage, and just reaches the control stick, forcing it forward. Now the plane reverses course, heading straight down, and tossing Pappy into the cockpit. The view of the Earth is reversed, looming closer and closer. Pappy seeks in vain any control or lever on the dashboard that might help him, and opens a hatch with a telephone inside. Pappy speaks frantically into the receiver: “Hello! Hello! How d’ya anchor this doggone sloop?” A telephone operator replies, “Sorry, sir. We can’t give you that information.”

Back at the hangar, Popeye, suiting up for a flight in the locker rom, hears an announcement over the airport P.A. system. “Whiskery old man in runaway plane is about to crash.” The microphone of the announcer remains live, as we hear the whistling descent of the plane, and a loud crash that shakes the rafters of the building. The announcer concludes, “That is all.” “That can’t be Pappy”, mutters Popeye, dismissing the importance of the announcement. “Oh, yes it can”, responds the all-knowing announcer. Popeye shouts in terror, “Me Pappy!”, and darts through the locker room door without bothering to open it. Outside, he finds the wreckage, and searches in vain for what has become of his Pop. But a call of “Ahoy” from far above reveals Pappy, safe and sound, hanging by his shirt from a water tower. The tower collapses, but Popeye catches the old sailor before the structure can crash down around him. Learning that Pappy is all right, Popeye’s sympathetic mood changes to anger again, and he orders Pappy to get out. Pappy trudges away, whimpering that he only wanted to be “an ace pilot like you”. Popeye feels complimented, and takes pity on the old coot, placing a pilot’s hat and wing medal upon his Pop, and telling him he can be a pilot after all. But a pilot of what? A large lawn mower, used for trimming the runway. But Pappy is satisfied, and mans his driver’s seat with all the poise of a movie pilot, for the iris out.

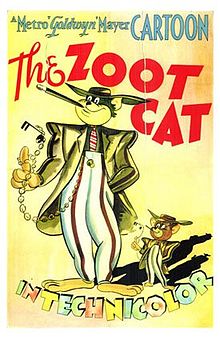

The Zoot Cat (MGM, Tom and Jerry, 2/26/44 – William Hanna/Joseph Barbera, dir.) Tom is in a familiar mode – out to impress a prospective girlfriend. Unfortunately, this being one of his early entries in the series, he is more unskilled and downright un-hip than usual. As a token of his affecton, he has dolled Jerry up in a ribbon, placed him in a velvet-lined hewelry case, and fastened a note to him reading, “Dear Toots. Roses are red. Violets are blue. Mice are nice…but Oh, you kid!”, then signing the note as “Sheikie”. Tom next dolls himself up, using lard as curling wax on his whiskers. A final dab of perfume on his temples, and under Jerry’s underarms, and Tom is off for the porch doorstep of his sweetie-to be. For once, the intended is not Toodles. Instead, she is a short gray/brown cat, dressed in orange blouse and yellow skirt, with a patch of blonde hair. Tom knocks, at the door, presses the bell buzzer, but blows the cool of his approach by yelling out, “Yoo Hoo! Hey, Toots!”, then hiding behind a porch post. He leaves the jewelry case on the doorstep, but the girl is noticeably disappointed at opening it to finf only Jerry, who, in one of his rare speaking moments, asks her in a bit sarcastic fashion, “What’s cookin’ Toots?” A whistle is heard from Tom, who emerges into view playing a 1920’s ukelele, and scatting “I’m a Ding Dong Daddy From Dumas”. He also demonstrates a yo-yo trick, the yo-yo string forming into the words, “Hi, Babe”. As he performs the final steps of a dance, and pulls out a bouquet of flowers for Toots, a porch board comes loose, whacking Tom in the face, and sending him bouncing down the steps to land on the front walkway. The girl’s reaction is a classic in being entirely unimpressed. “Boy, are you corny. You act like a square for fair. A goon from Saskatoon. You come on like a broken arm. You’re a sad apple. A longhair. A corn-husker. In other words, ya’ don’t send me. So bail out, brother. Get lost. And here’s your rat, cat.” Jerry and the jewelry case are tossed back at the astonished Tom, and Jerry adds his own concurrence with the girl’s opinion, by placing into Tom’s paws a ripe ear of corn.

The Zoot Cat (MGM, Tom and Jerry, 2/26/44 – William Hanna/Joseph Barbera, dir.) Tom is in a familiar mode – out to impress a prospective girlfriend. Unfortunately, this being one of his early entries in the series, he is more unskilled and downright un-hip than usual. As a token of his affecton, he has dolled Jerry up in a ribbon, placed him in a velvet-lined hewelry case, and fastened a note to him reading, “Dear Toots. Roses are red. Violets are blue. Mice are nice…but Oh, you kid!”, then signing the note as “Sheikie”. Tom next dolls himself up, using lard as curling wax on his whiskers. A final dab of perfume on his temples, and under Jerry’s underarms, and Tom is off for the porch doorstep of his sweetie-to be. For once, the intended is not Toodles. Instead, she is a short gray/brown cat, dressed in orange blouse and yellow skirt, with a patch of blonde hair. Tom knocks, at the door, presses the bell buzzer, but blows the cool of his approach by yelling out, “Yoo Hoo! Hey, Toots!”, then hiding behind a porch post. He leaves the jewelry case on the doorstep, but the girl is noticeably disappointed at opening it to finf only Jerry, who, in one of his rare speaking moments, asks her in a bit sarcastic fashion, “What’s cookin’ Toots?” A whistle is heard from Tom, who emerges into view playing a 1920’s ukelele, and scatting “I’m a Ding Dong Daddy From Dumas”. He also demonstrates a yo-yo trick, the yo-yo string forming into the words, “Hi, Babe”. As he performs the final steps of a dance, and pulls out a bouquet of flowers for Toots, a porch board comes loose, whacking Tom in the face, and sending him bouncing down the steps to land on the front walkway. The girl’s reaction is a classic in being entirely unimpressed. “Boy, are you corny. You act like a square for fair. A goon from Saskatoon. You come on like a broken arm. You’re a sad apple. A longhair. A corn-husker. In other words, ya’ don’t send me. So bail out, brother. Get lost. And here’s your rat, cat.” Jerry and the jewelry case are tossed back at the astonished Tom, and Jerry adds his own concurrence with the girl’s opinion, by placing into Tom’s paws a ripe ear of corn.

Tom pursues Jerry across the porch, but merely slams his head into the porch railing as Jerry escapes. Suddenly, the girl’s words come back to him again, but in a different voice. “Boy, are you corny. How many times have you been told that?” It is an announcer on the radio in the girl’s parlor, doing a commercial. “Get your boots laced, buddy. Get hep to the juve. Step in and see Smilin’ Sam, the Zoot suit man.” Tom hears the announcer expound the virtues of an ankle-length jacket with three-foot shoulders. Tanks that begin at the chin, zoom to a 54 inch knee, then fade softly to a three-inch victory cuff. Well, Tom has the required measurements. All he needs is the materials. Grabbing a lamp shade from just inside the window of Toots’ living room, Tom compresses it down into the shape of a wide-brimmed hat. Next, a pair of garden shears, and the orange and yellow-striped fabric cut from Toots’ porch hammock. A little sewing, never shown on screen, and voila – Tom re-appears at the door, dressed to the nines in the loudest and most modern of zoot suits! He shows off his threads as both the girl’s and Jerry’s eyes literally pop. Tom makes sure his shoulders extend out to maximum width, by inserting a wooden coat hanger just inside the back of the suit’s collar. Toots invites him in, declaring that now he’s really a sharp character – “A mellow little fellow”. She invites him to “Slip me some skin”, then “Latch on” for some “righteous jive”. With a call of “We’re off”, the two cats break into an impromptu jitterbug that closely approximates what would later become known as Snoopy’s “happy dance” – lots of stepping, but staying in one place. From a table top, Jerry taps Tom on the shoulder, and cuts in, taking the girl’s hand to join in the dancing. Tom suddenly realizes, why am I letting this happen, and the traditional chase between cat and mouse begins.

Tom pursues Jerry across the porch, but merely slams his head into the porch railing as Jerry escapes. Suddenly, the girl’s words come back to him again, but in a different voice. “Boy, are you corny. How many times have you been told that?” It is an announcer on the radio in the girl’s parlor, doing a commercial. “Get your boots laced, buddy. Get hep to the juve. Step in and see Smilin’ Sam, the Zoot suit man.” Tom hears the announcer expound the virtues of an ankle-length jacket with three-foot shoulders. Tanks that begin at the chin, zoom to a 54 inch knee, then fade softly to a three-inch victory cuff. Well, Tom has the required measurements. All he needs is the materials. Grabbing a lamp shade from just inside the window of Toots’ living room, Tom compresses it down into the shape of a wide-brimmed hat. Next, a pair of garden shears, and the orange and yellow-striped fabric cut from Toots’ porch hammock. A little sewing, never shown on screen, and voila – Tom re-appears at the door, dressed to the nines in the loudest and most modern of zoot suits! He shows off his threads as both the girl’s and Jerry’s eyes literally pop. Tom makes sure his shoulders extend out to maximum width, by inserting a wooden coat hanger just inside the back of the suit’s collar. Toots invites him in, declaring that now he’s really a sharp character – “A mellow little fellow”. She invites him to “Slip me some skin”, then “Latch on” for some “righteous jive”. With a call of “We’re off”, the two cats break into an impromptu jitterbug that closely approximates what would later become known as Snoopy’s “happy dance” – lots of stepping, but staying in one place. From a table top, Jerry taps Tom on the shoulder, and cuts in, taking the girl’s hand to join in the dancing. Tom suddenly realizes, why am I letting this happen, and the traditional chase between cat and mouse begins.

In the course of the pursuit, Tom is launched across the keyboard of a grand piano, but recovers his composure, seating himself at the piano bench, and displaying his keyboard technique, playing a romantic solo of the strains of “Deep Purple.” His playing has Toots really sent, and Yom breaks into romantic patter in a voice impersonating leading man Charles Boyer. (Most of ths dialogue would be re-used from the track verbatim in the later cartoon, “Solid Serenade”.) Tom begins talking about feeling not just “a little spark, but a big, roaring flame” from his romantic feelings about her. Jerry meanwhile is inserting most of a match book into the soles of Tom’s shoes, for a colossal hotfoot. As smoke rises to the level of Tom’s nostrils, Tom sniffs the air, and remarks to the audience in a voice approximating Groucho Marx, “Say, something is burning around here.” A scream, and Tom takes off to the ceiling like a comet. As the film approaches its conclusion, Tom looks around for Jerry, in close proximity to a lowered windowshade. Jerry slips up on the windowsill behind him, and hooks the coat-hanger inside Tom’s collar to the pull-loop of the windowshade cord. Then Jerry gets Tom to chase him. The windowshade extends along with the cord to its limit, then snaps back, pulling Tom into the air. Tom rolls around within the shade several times, falls out, and gets doused in a large fishbowl below the level of the windowsill. The shade snaps back again, and Tom repeats the dunking process about three times. With excruciating sounds of massive shrinkage, the suit fabric begins to contract and shrink upon Tom’s person, pitting the cat into a stranglehold as the suit becomes many times smaller than his actual size. (Now, if this fabric came from an outdoor hammock, which presumably should be treated to handle all kinds of weather, including rain, why does it shrink from the goldfish water?) The suit, unable to take more stress, pops off Tom, each article drifting slowly downwards like the drifting of a feather in the breeze. Jerry stands below, and hops into each item as it arrives at his level. Thus, Jerry acquires a custom-fitted zoot suit of his own, and makes a slick exit behind the window curtains, briefly re-emerging to tip his hat to the audience, for the iris out.

In the course of the pursuit, Tom is launched across the keyboard of a grand piano, but recovers his composure, seating himself at the piano bench, and displaying his keyboard technique, playing a romantic solo of the strains of “Deep Purple.” His playing has Toots really sent, and Yom breaks into romantic patter in a voice impersonating leading man Charles Boyer. (Most of ths dialogue would be re-used from the track verbatim in the later cartoon, “Solid Serenade”.) Tom begins talking about feeling not just “a little spark, but a big, roaring flame” from his romantic feelings about her. Jerry meanwhile is inserting most of a match book into the soles of Tom’s shoes, for a colossal hotfoot. As smoke rises to the level of Tom’s nostrils, Tom sniffs the air, and remarks to the audience in a voice approximating Groucho Marx, “Say, something is burning around here.” A scream, and Tom takes off to the ceiling like a comet. As the film approaches its conclusion, Tom looks around for Jerry, in close proximity to a lowered windowshade. Jerry slips up on the windowsill behind him, and hooks the coat-hanger inside Tom’s collar to the pull-loop of the windowshade cord. Then Jerry gets Tom to chase him. The windowshade extends along with the cord to its limit, then snaps back, pulling Tom into the air. Tom rolls around within the shade several times, falls out, and gets doused in a large fishbowl below the level of the windowsill. The shade snaps back again, and Tom repeats the dunking process about three times. With excruciating sounds of massive shrinkage, the suit fabric begins to contract and shrink upon Tom’s person, pitting the cat into a stranglehold as the suit becomes many times smaller than his actual size. (Now, if this fabric came from an outdoor hammock, which presumably should be treated to handle all kinds of weather, including rain, why does it shrink from the goldfish water?) The suit, unable to take more stress, pops off Tom, each article drifting slowly downwards like the drifting of a feather in the breeze. Jerry stands below, and hops into each item as it arrives at his level. Thus, Jerry acquires a custom-fitted zoot suit of his own, and makes a slick exit behind the window curtains, briefly re-emerging to tip his hat to the audience, for the iris out.

• Watch ZOOT CAT on DailyMotion.

NEXT WEEK: Super-heroes, crooning, and more pretty girls – as the ‘40’s progress, next time. Happy New Year to all!