Our second look at the misadventures animated characters can experience when they face the “culture shock” of changing fads and fancies. Cartoons were apt to play upon the personal sensibilities of their viewers, among whom most if not all had at some point in their lives felt they were not quite hip or trendy enough to keep pace with their circle of friends (or disinterested strangers), often leading to drastic efforts at makeovers or finding some way to stand out positively in a crowd. Seeing well-known screen characters experiencing the same awkward moments tended to imbue them with “personality”, and make them more relatable to living human beings – thus almost inevitably ensuring a sort of emotional bonding with the faltering underdog, or at least guaranteeing laughs of the snickering variety from those who considered themselves at the top of the social heap, who would revel in the same enjoyment they found in real life at ridiculing how un-cool some people could be. A good plot formula, all in all.

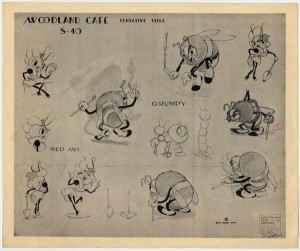

Woodand Café (Disney/UA, Silly Symphony, 3/13/37 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.). This is one of those wonderful pieces of animation history that has never been surpassed or equalled. It has no plot (perhaps a bit offputting to a youthful audience looking for hilarious gags or a string storyline), but is a film that grows on you with every rewatching, for its fine detail, complexity of animation, rich character designs, and pure energy. It is a film time capsule of urban night life at its best, or at least, as it should have been in our finest expectations – although the entire entertainment is presented from a bug’s eye view in a fantasy universe somewhere in an unidentified forest. All manner of attendees and behind-the-scenes personnel making the night possible are represented – taxi drivers, valets, hat check girls, waiters, fireflies supplying table lighting and neon sign illumination, centipedes dressed in top hat, tails, and gloves (LOTS of gloves!), an elderly couple of snails, two chic ladybug twins showing off their dance moves, squirming worm dancers, a specialty dancing team of a spider and a fly, and a hot Harlem grasshopper jazz band. For those with an open mind to the film’s times and intentions. the mood of the piece (complete in every detail down to the lounging, lazy poses of some of the orchestra in their quieter moments, a many-armed waiter taking two orders at the same time, and still having enough free hands to find one capable of wiping his nose, and the effervescence of the contents of a vintage cherry when popped open and poured into a glass) is absolutely infectious, and by the end of the short (which almost comes too soon), you feel as though you have truly witnessed a celebration for all time. A perfect view for the holiday season, or any time of reason to mark a day as special.

Woodand Café (Disney/UA, Silly Symphony, 3/13/37 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.). This is one of those wonderful pieces of animation history that has never been surpassed or equalled. It has no plot (perhaps a bit offputting to a youthful audience looking for hilarious gags or a string storyline), but is a film that grows on you with every rewatching, for its fine detail, complexity of animation, rich character designs, and pure energy. It is a film time capsule of urban night life at its best, or at least, as it should have been in our finest expectations – although the entire entertainment is presented from a bug’s eye view in a fantasy universe somewhere in an unidentified forest. All manner of attendees and behind-the-scenes personnel making the night possible are represented – taxi drivers, valets, hat check girls, waiters, fireflies supplying table lighting and neon sign illumination, centipedes dressed in top hat, tails, and gloves (LOTS of gloves!), an elderly couple of snails, two chic ladybug twins showing off their dance moves, squirming worm dancers, a specialty dancing team of a spider and a fly, and a hot Harlem grasshopper jazz band. For those with an open mind to the film’s times and intentions. the mood of the piece (complete in every detail down to the lounging, lazy poses of some of the orchestra in their quieter moments, a many-armed waiter taking two orders at the same time, and still having enough free hands to find one capable of wiping his nose, and the effervescence of the contents of a vintage cherry when popped open and poured into a glass) is absolutely infectious, and by the end of the short (which almost comes too soon), you feel as though you have truly witnessed a celebration for all time. A perfect view for the holiday season, or any time of reason to mark a day as special.

Amidst all the splendor and merrymaking comes an elderly and crochety-looking old bee. He walks with difficulty in stoop-shouldered fashion, using a cane for wobbly support and ambling across the club at decidely slow gait. One can instantly tell, however, that he is an insect of influence, and no doubt well-to-do, as, despite his dour countenance and personality, he is cheerily escorted by a waiter with instant recognition of him to the choicest of tables. Another clear indicator of his wealth and power is that he is accompanied to the event by an energetic and shapely female bug who appears to be no more than half his age – someone no doubt attracted to him more for his bankroll than for any physical or emotional attributes. The rich and expressive animation fully conveys without a word of dialog the personality traits of the bee, as his legs fumble for a comfortable position even during the simple act of sitting down, , and the waiter’s best attentions are able to raise no more than a bored-with-life nod of half-approval as the bee inspects the vintage cherry brought up specially for him from the club’s wine cellar. We never see the bee drink the stuff, so we never really discern if he even bothered to touch his glass during the evening. There is certainly no sign of his having stooped to intoxication to provide himself with any level of diversion. One entirely gets the feeling from the expressiveness of the animation that, either it was the girl’s idea to come here in the first place, or the bee merely frequents the club as a sign of stature and social position, as if expected of one from his plateau of financial strata.

Amidst all the splendor and merrymaking comes an elderly and crochety-looking old bee. He walks with difficulty in stoop-shouldered fashion, using a cane for wobbly support and ambling across the club at decidely slow gait. One can instantly tell, however, that he is an insect of influence, and no doubt well-to-do, as, despite his dour countenance and personality, he is cheerily escorted by a waiter with instant recognition of him to the choicest of tables. Another clear indicator of his wealth and power is that he is accompanied to the event by an energetic and shapely female bug who appears to be no more than half his age – someone no doubt attracted to him more for his bankroll than for any physical or emotional attributes. The rich and expressive animation fully conveys without a word of dialog the personality traits of the bee, as his legs fumble for a comfortable position even during the simple act of sitting down, , and the waiter’s best attentions are able to raise no more than a bored-with-life nod of half-approval as the bee inspects the vintage cherry brought up specially for him from the club’s wine cellar. We never see the bee drink the stuff, so we never really discern if he even bothered to touch his glass during the evening. There is certainly no sign of his having stooped to intoxication to provide himself with any level of diversion. One entirely gets the feeling from the expressiveness of the animation that, either it was the girl’s idea to come here in the first place, or the bee merely frequents the club as a sign of stature and social position, as if expected of one from his plateau of financial strata.

However, as the evening progresses to its climax, the grasshopper band breaks into it’s feature number of the evening – Duke Ellington’s “Truckin’”. Virtually everyone in the club is on their feet (or whatever propels them) and on the dance floor, as rotating balls of fireflies illuminate the floor with a dazzling light display. So what of the bee? At his table, the spirit of the music has caught up his girlfriend, who breaks into a sensuous dance of rhythmic abandon atop the table. The bee finds even his hardened heart and rickety body can’t be contained, and his ankles begin to react reflexively to the beat of the music. The bee stands, and attempts to concentrate on centering the weight of his large body in a manner to allow him to shift his torso into dance moves. He still continues to have balance problems, a few times almost stumbling forward so that his cane looks ready to double over or snap in two. But still he remains game and determined to give it his best shot, a sort of wry smile spreading over his face. After extended shots of the band and other dancers, the camera returns to the bee’s table. Somehow, he has managed to get up atop the table, and is doing his best to match the swiveling steps of his girlfriend – though we see the odd touch of wisps of smoldering smoke wafting from the soles of his shoes. We cut away again to other shots, then, shortly before the end of the film, see a view of the bee, being carried out of the club upon a stretcher by two ambulance attendants (although they appear to be in no hurry, perhaps having encountered the bee in this condition on previous occasions). The bee himself is still conscious (at least, semi-so), although appearing considerably dazed and disoriented. His shoes seem to have worn through at the soles, and still smolder quite visibly. But the bee seems to have finally learned to enjoy himself, and leaves the event with a broad smile on his face, and one finger continuing to waggle back and forth in the classic “trucking”: dance pose. He got with the times – and liked it.

However, as the evening progresses to its climax, the grasshopper band breaks into it’s feature number of the evening – Duke Ellington’s “Truckin’”. Virtually everyone in the club is on their feet (or whatever propels them) and on the dance floor, as rotating balls of fireflies illuminate the floor with a dazzling light display. So what of the bee? At his table, the spirit of the music has caught up his girlfriend, who breaks into a sensuous dance of rhythmic abandon atop the table. The bee finds even his hardened heart and rickety body can’t be contained, and his ankles begin to react reflexively to the beat of the music. The bee stands, and attempts to concentrate on centering the weight of his large body in a manner to allow him to shift his torso into dance moves. He still continues to have balance problems, a few times almost stumbling forward so that his cane looks ready to double over or snap in two. But still he remains game and determined to give it his best shot, a sort of wry smile spreading over his face. After extended shots of the band and other dancers, the camera returns to the bee’s table. Somehow, he has managed to get up atop the table, and is doing his best to match the swiveling steps of his girlfriend – though we see the odd touch of wisps of smoldering smoke wafting from the soles of his shoes. We cut away again to other shots, then, shortly before the end of the film, see a view of the bee, being carried out of the club upon a stretcher by two ambulance attendants (although they appear to be in no hurry, perhaps having encountered the bee in this condition on previous occasions). The bee himself is still conscious (at least, semi-so), although appearing considerably dazed and disoriented. His shoes seem to have worn through at the soles, and still smolder quite visibly. But the bee seems to have finally learned to enjoy himself, and leaves the event with a broad smile on his face, and one finger continuing to waggle back and forth in the classic “trucking”: dance pose. He got with the times – and liked it.

Several other studios would attempt to capture the same theme, without the side-angle of enlivening a wallflower, such as in Terrytoons’ “Bugs Beetle ad His Orchestra”, or Walter Lantz’s “I’m Just a Jitterbug”. But nome of these productions even came close to matching the dynamics and atmosphere of the Disney work. A testament to how head-and-shoulders above the competition Disney could be when it put its back into a project.

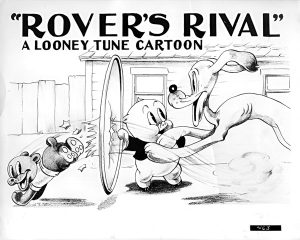

Rover’s Rival (Warner, Porky Pig, 10/9/37 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – Perhaps one of the first cartoons to explore the phenomena of the “generation gap”, where the obstacle to a character’s success is not so much any matter of his personal tastes, but the sheer advancement of years. To a more indirect degree (as it is treated more as a cure of an illness rather than an update in social status), a prior instance bordering on the subject might be Van Beiren’s “Red Riding Hood” (1931), where an aged grandma is rejuvenated into a modern vamp by means of a doctor’s dose of “jazz tonic”. But this was more consistent with the old “Fountain of Youth” legend rather than so much of a social commentary (a theme briefly used again in “Betty Boop. M/D/” (1932), where a dose of Gippo turns an old man young, and a young man old). Here, however, Clampett addresses the age issue without the assistance of a miracle elixir, giving the story a then unique, and sometimes unsettling, vantage point upon the way youth will sometimes display utter disrespect for the abilities or accumulated wisdom of their elders.

Rover’s Rival (Warner, Porky Pig, 10/9/37 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – Perhaps one of the first cartoons to explore the phenomena of the “generation gap”, where the obstacle to a character’s success is not so much any matter of his personal tastes, but the sheer advancement of years. To a more indirect degree (as it is treated more as a cure of an illness rather than an update in social status), a prior instance bordering on the subject might be Van Beiren’s “Red Riding Hood” (1931), where an aged grandma is rejuvenated into a modern vamp by means of a doctor’s dose of “jazz tonic”. But this was more consistent with the old “Fountain of Youth” legend rather than so much of a social commentary (a theme briefly used again in “Betty Boop. M/D/” (1932), where a dose of Gippo turns an old man young, and a young man old). Here, however, Clampett addresses the age issue without the assistance of a miracle elixir, giving the story a then unique, and sometimes unsettling, vantage point upon the way youth will sometimes display utter disrespect for the abilities or accumulated wisdom of their elders.

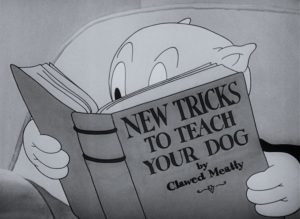

Porky is excitedly reading a volume on New Tricks to Teach Your Dog, by Clawed Meatly (pun on well-known wild animal trainer Clyde Beatty). He runs outside to show them to Rover – a dog so old, decrepit, and rickety, that his skeletal bone frame clanks against itself with every belabored, feeble movement. A simple command of “sit up” pops every vertebrae louder than a chiropractor’s treatment. “Roll over” is another challenge, Rover struggling to make it even half-way. Along comes a little black puppy, presumably the dog of a neighbor. Spying Rover’s difficulties, the pup knowingly points him out to the audience, as if to wise-crack, “Get him”, and trots into Porky’s yard. As Rover tries to roll over once more, the pup merely blows some wind at his legs, tottering Rover back to where he started. Porky shifts gears, and holds up a paper hoop for Rover to jump through. The over-eager pup jumps through it first, spoiling the paper. Porky lowers the hoop, leaving Rover to mistakenly jump past where it was held, and crash face-first unto the bottom of a metal washtub hanging on a wall.

Porky is excitedly reading a volume on New Tricks to Teach Your Dog, by Clawed Meatly (pun on well-known wild animal trainer Clyde Beatty). He runs outside to show them to Rover – a dog so old, decrepit, and rickety, that his skeletal bone frame clanks against itself with every belabored, feeble movement. A simple command of “sit up” pops every vertebrae louder than a chiropractor’s treatment. “Roll over” is another challenge, Rover struggling to make it even half-way. Along comes a little black puppy, presumably the dog of a neighbor. Spying Rover’s difficulties, the pup knowingly points him out to the audience, as if to wise-crack, “Get him”, and trots into Porky’s yard. As Rover tries to roll over once more, the pup merely blows some wind at his legs, tottering Rover back to where he started. Porky shifts gears, and holds up a paper hoop for Rover to jump through. The over-eager pup jumps through it first, spoiling the paper. Porky lowers the hoop, leaving Rover to mistakenly jump past where it was held, and crash face-first unto the bottom of a metal washtub hanging on a wall.

The pup confronts Rover, and sarcastically tries to wise him up to the old adage that you can’t teach an old dog new tricks. Rover disagrees, calling the pup just a young whippersnapper. Porky tries again, asking Rover to catch a ball tossed into the air. Rover opens hus mouth to receive the ball, but the pip tosses into his mouth an oversized pumpkin, leaving the ball free for him to catch himself. The pup mimics Rover’s speech patterns, calling him, “one of them thar used-to-wuzzes”. Porky tells the pup not to imitate Rover, stating he’s sensitive. The pup responds with a perfect impression of Porky: “G-g-gee, I’m sorry to hear th-th-th-that!”

The pup continues to barge in on Rover’s lessons, developing into a contest of who can best fetch a stick. The pup keeps stealing the stick away, right out of Rover’s jaws – even showing up at Porky’s feet, not only with stick retrieved, but also wearing Rover’s full set of false teeth. Porky insists now it’s Rover’s turn, and tackles the pup before he can interfere with the trick again. Rover follows the stick into a nearby construction yard, where a sign reads, “Danger! We’re gonna blast.” Unable to find the real stick. Rover mistakenly retrieves a stick of dynamite from the lot, and returns it to Porky. Porky shows off to the pup what Rover has done – until he reads the identifying word on the side of the retrieved “stick”. “DYNAMITE??” Porky throws the stick off the property, but Rover, surprised at the word spoken by Porky (and possibly suffering from a lapse of memory as to its definition), runs upstairs to Porky’s study, to look the word up in the dictionary. Meanwhile, the eager pup also follows the “stick” into the construction yard, and spots a nearby crate full of identical sticks. When he returns to Porky, he not only bears the first stick, but the entire contents of the crate, which he passes to Porky one by one. Porky tosses them away as fast as he can, but the pup positions himself between Porky and the adjoining lot, and tosses each stick back to Porky as fast as he can throw them. Porky falls backwards upon the ground, his arms, mouth, and ears chock full of the dynamite sticks. The pup inquires if Porky has a match, and upon receiving one, lights all the fuses uf the sticks unmercifully. He remains one step ahead of Porky wherever the pig tries to hide, and ultimately pins Porky into a corner surrounded by the lit sticks, with Porky saying his prayers.

The pup continues to barge in on Rover’s lessons, developing into a contest of who can best fetch a stick. The pup keeps stealing the stick away, right out of Rover’s jaws – even showing up at Porky’s feet, not only with stick retrieved, but also wearing Rover’s full set of false teeth. Porky insists now it’s Rover’s turn, and tackles the pup before he can interfere with the trick again. Rover follows the stick into a nearby construction yard, where a sign reads, “Danger! We’re gonna blast.” Unable to find the real stick. Rover mistakenly retrieves a stick of dynamite from the lot, and returns it to Porky. Porky shows off to the pup what Rover has done – until he reads the identifying word on the side of the retrieved “stick”. “DYNAMITE??” Porky throws the stick off the property, but Rover, surprised at the word spoken by Porky (and possibly suffering from a lapse of memory as to its definition), runs upstairs to Porky’s study, to look the word up in the dictionary. Meanwhile, the eager pup also follows the “stick” into the construction yard, and spots a nearby crate full of identical sticks. When he returns to Porky, he not only bears the first stick, but the entire contents of the crate, which he passes to Porky one by one. Porky tosses them away as fast as he can, but the pup positions himself between Porky and the adjoining lot, and tosses each stick back to Porky as fast as he can throw them. Porky falls backwards upon the ground, his arms, mouth, and ears chock full of the dynamite sticks. The pup inquires if Porky has a match, and upon receiving one, lights all the fuses uf the sticks unmercifully. He remains one step ahead of Porky wherever the pig tries to hide, and ultimately pins Porky into a corner surrounded by the lit sticks, with Porky saying his prayers.

Meanwhile, Rover has finally found the definition of dynamite – a high explosive. That’s enough to send Rover flying out the door to Porky’s rescue. The pup tries to interfere with Rover’s rounding up of the sticks, but ultimately gets pinned helplessly to a tree limb, suspended there by Rover’s false teeth. Rover bravely shakes Porky’s hand goodbye, and darts out of frame with the dynamite. A huge explosion occurs offscreen, and the construction sign lands in Porky’s yard, its inscription changed to “We’ve blasted.” Rover lies prone and seemingly unconscious upon the ground, with dirt covering portions of his limbs and torso, making him appear to be severed and dismembered. The pup finally shows a moment of humanity and remorse, holding Rover’s limp paw, and confessing that Rover wasn’t a “used-to-wuzzer”, but the beast stick retriever ever. Rover ends the film by opening his eyes, rising to a seated position which brushes off the dirt to reveal him in one piece, and excitedly asking the pup, “Do you mean it?”

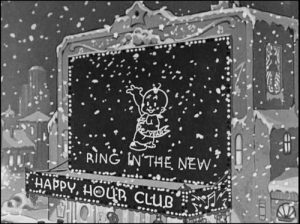

We’re a few weeks early, but it seems the subject of one of the only cartoons produced about New Year’s Eve inevitably rolls around. Let’s Celebrake (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 1/21/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/William Henning, anim.) finds Popeye and Bluto for once not scuffling amongst themselves, apparently willing to share the affections of Olive for one evening so that everyone can make merry. Well, perhaps not everyone. We are introduced to an elderly relation of Olive, referred to only as Grandma, who is extremely hard of hearing, can only walk in slow, wobbly fashion, and seems resigned to remain by the fireside alone on the holiday while Olive steps out in her best finery to cavort. Popeye just can’t stand by and watch what seems to be the most pitiful of ways to spend a night meant for festivity, so volunteers to turn the evening into a double-date, relinquishing Olive for once to Bluto, while he himself sets his sails for finding some means to add Grandma to the ranks of the still-alive-and-kicking.

We’re a few weeks early, but it seems the subject of one of the only cartoons produced about New Year’s Eve inevitably rolls around. Let’s Celebrake (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 1/21/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/William Henning, anim.) finds Popeye and Bluto for once not scuffling amongst themselves, apparently willing to share the affections of Olive for one evening so that everyone can make merry. Well, perhaps not everyone. We are introduced to an elderly relation of Olive, referred to only as Grandma, who is extremely hard of hearing, can only walk in slow, wobbly fashion, and seems resigned to remain by the fireside alone on the holiday while Olive steps out in her best finery to cavort. Popeye just can’t stand by and watch what seems to be the most pitiful of ways to spend a night meant for festivity, so volunteers to turn the evening into a double-date, relinquishing Olive for once to Bluto, while he himself sets his sails for finding some means to add Grandma to the ranks of the still-alive-and-kicking.

The remainder of the cartoon might be classified as a sort of remake of “The Dance Contest”, with the quartet attending a gala bash at the Happy Hour night club (again presided over by Wimpy, but with no hamburgers in sight), and the festivities climaxing in a dance contest. Before the dancing begins, Popeye attempts to keep Grandma smiling, by blowing an extending party blower across the table, to tickle Granny under her chin. Bluto and Olive are quite bored with this and show no degree of understanding or sympathy for Popeye’s effort, so leave the sailor and Granny alone while enjoying themselves on the dance floor. Popeye decides to see if he can coax Granny out on the floor too, but finds that, while he attempts to circle her with easy but energetic steps and get her to follow his lead, Granny mostly stands in place still, and will barely lift her feet. As the contest mode begins, Popeye, though displaying no specific aspirations for any chance to win the cup, can see that Granny’s abilitieas are strictly from nowhere, and decides to fall back upon his own personal version of the Fountain of Youth – a spinach can, being delivered to the table by a waiter. (Isn’t it odd that all these swanky night spots have spinach on the menu – this one still in the can rather than a bowl!) Popeye himself must still remember by heart his spinach-induced dance moves from the previous cartoon, as he chooses not to ingest any of the leafy vegetable himself, but instead feeds the whole can to Grandma. Though Grandma undergoes no facial or anatomical changes, her vigor and abilities seem to be restored to an age of about 22 again, and the classic wallflower blooms into a show-stopping hoofer, as Popeye and Granny whirl within the circle of dancers, making wider and wider circular loops to clear the center of the floor for their high-stepping display. Bluto and Olive, now pushed to the sidelines, still display no sympathy or approval toward this development, and Olive even mutters under her breath. “Get her.” While there is more pep, high-kicking, and sheer number of drawings involved in the extended dancing sequence than in the predecessor cartoon, for my money, I still tend to think of “The Dance Contest”’s choreography as more entertaining and original. Some of the new moves incorporate steps that might border on jitterbugging, and another scene incorporates “Truckin’”, with one finger waggling in the air. Popeye still manages to take one chorus of the music in Sailor’s Hornpipe mode, even adding the dance gestures of “climbing rope” from the traditional steps – and Granny gets the idea, matching him move for move. Some of the last steps seem borrowed from previous Betty Boop cartoons, with Granny mimicking a move from “Betty Boop’s Trial”, and Popeye and her performing a series of cross-kick moves that seem to be lifted from “Betty Boop and Grampy”. Of course (and in rather hurried fashion, with no mustard involved). Popeye and Granny win the cup, and balloons and floodlights pour down upon the floor at the stroke of 12, for the iris out.

The remainder of the cartoon might be classified as a sort of remake of “The Dance Contest”, with the quartet attending a gala bash at the Happy Hour night club (again presided over by Wimpy, but with no hamburgers in sight), and the festivities climaxing in a dance contest. Before the dancing begins, Popeye attempts to keep Grandma smiling, by blowing an extending party blower across the table, to tickle Granny under her chin. Bluto and Olive are quite bored with this and show no degree of understanding or sympathy for Popeye’s effort, so leave the sailor and Granny alone while enjoying themselves on the dance floor. Popeye decides to see if he can coax Granny out on the floor too, but finds that, while he attempts to circle her with easy but energetic steps and get her to follow his lead, Granny mostly stands in place still, and will barely lift her feet. As the contest mode begins, Popeye, though displaying no specific aspirations for any chance to win the cup, can see that Granny’s abilitieas are strictly from nowhere, and decides to fall back upon his own personal version of the Fountain of Youth – a spinach can, being delivered to the table by a waiter. (Isn’t it odd that all these swanky night spots have spinach on the menu – this one still in the can rather than a bowl!) Popeye himself must still remember by heart his spinach-induced dance moves from the previous cartoon, as he chooses not to ingest any of the leafy vegetable himself, but instead feeds the whole can to Grandma. Though Grandma undergoes no facial or anatomical changes, her vigor and abilities seem to be restored to an age of about 22 again, and the classic wallflower blooms into a show-stopping hoofer, as Popeye and Granny whirl within the circle of dancers, making wider and wider circular loops to clear the center of the floor for their high-stepping display. Bluto and Olive, now pushed to the sidelines, still display no sympathy or approval toward this development, and Olive even mutters under her breath. “Get her.” While there is more pep, high-kicking, and sheer number of drawings involved in the extended dancing sequence than in the predecessor cartoon, for my money, I still tend to think of “The Dance Contest”’s choreography as more entertaining and original. Some of the new moves incorporate steps that might border on jitterbugging, and another scene incorporates “Truckin’”, with one finger waggling in the air. Popeye still manages to take one chorus of the music in Sailor’s Hornpipe mode, even adding the dance gestures of “climbing rope” from the traditional steps – and Granny gets the idea, matching him move for move. Some of the last steps seem borrowed from previous Betty Boop cartoons, with Granny mimicking a move from “Betty Boop’s Trial”, and Popeye and her performing a series of cross-kick moves that seem to be lifted from “Betty Boop and Grampy”. Of course (and in rather hurried fashion, with no mustard involved). Popeye and Granny win the cup, and balloons and floodlights pour down upon the floor at the stroke of 12, for the iris out.

• Check out LETS CELEBRAKE on DailyMotion

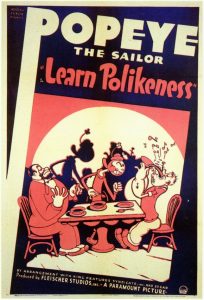

Learn Polikeness (Fleischer/Paramount Popeye, 2/18/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., David Tendlar/Nicholas Tafuri, anim.) – Popeye’s first venture into the uncharacteristic atmosphere of fine manners. Bluto has attempted to clean up his act, opening a new line of business – Prof. Bluteau’s School of Etiquette (with the motto, “For a little dough, you can be well bred”). In a swank penthouse campus atop the “Fine Manor Apartments”, we find that it isn’t necessary to put on airs when nobody’s looking – thus, we get a secret glimpse at the real Bluto in his private office – dressed in an undershirt, his feet up on the desk clad only in stockings with holes in the toes, awkwardly chomping and gulping down a banana while reading a book entitled “Cops and Robbers”. Passing by below arrive the inevitable cash customers: Olive, dragging Popeye in to become a refined gentleman. Hearing the doorbell, Bluto is quick to revert to professional form, and with a few quick moves, has outfitted himself in tuxedo, fancy shoes and vest. “Entree”, he greets them at the door. “I already ‘et”, retorts Popeye, misunderstanding the professor’s lingo. “I want this to become a gentleman”, Olive tells Bluto. Bluto pulls out a monocle and closely observes Popeye. “Not so good…I wonder if that thing is human”, he mutters. Bluto’s first move is to throw Popeye’s pipe away into a nearby planter, where a daisy withers from the smell of its smoke. “Hey, what’s the idea? Do ya wanna spoil the flavor?”, complains Popeye. Bluto next demonstrates the proper way to greet a lady, making a low bow, taking Olive’s hand and kissing it. “Merci Bouquet”, responds Olive. Popeye shows his own idea of how to greet a lady – unceremoniously running up to her, shaking her hand vigorously, and complimenting her with “Well shiver me timbers! You’re the trimmest little craft I ever seen.” With disdain toward Popeye, Bluto demonstrates how to escort Olive up a flight of stairs. “She was always able to walk up herself before”, mumbles Popeye. Bluto directs Popeye to escort her back down. Popeye does so by seating Olive on the staircase railing, pushing her into a rapid downhill slide, then catching her on the other end. “Voulex voulez voo, and I do mean you”, says Popeye in a bow. Bluto’s third lesson demonstrates how to put on, then remove, a lady’s wrap. Seeing the garment go on and off so quickly, Popeye asks why’d he put it on her in the first place. Bluto asks Popeye to do it. Popeye tosses the coat into the air, then tickles Olive under the arms, causing her to raise her limbs high above her head, just in time to receive the falling coat. However, removing the wrap isn’t so easy, as Popeye yanks it down instead of up, flipping Olive’s feet out from under her in a backwards pratfall. Olive is disgusted, and Bluto grabs a book of etiquette, tosses it in Popeye’s face, and tells him, “Read this, and come back in ten years!”. Popeye crashes into the opposite wall, dislodging a painting. Its frame falls off, and the canvas wraps itself around Popeye’s head in the shape of a dunce cap.

Learn Polikeness (Fleischer/Paramount Popeye, 2/18/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., David Tendlar/Nicholas Tafuri, anim.) – Popeye’s first venture into the uncharacteristic atmosphere of fine manners. Bluto has attempted to clean up his act, opening a new line of business – Prof. Bluteau’s School of Etiquette (with the motto, “For a little dough, you can be well bred”). In a swank penthouse campus atop the “Fine Manor Apartments”, we find that it isn’t necessary to put on airs when nobody’s looking – thus, we get a secret glimpse at the real Bluto in his private office – dressed in an undershirt, his feet up on the desk clad only in stockings with holes in the toes, awkwardly chomping and gulping down a banana while reading a book entitled “Cops and Robbers”. Passing by below arrive the inevitable cash customers: Olive, dragging Popeye in to become a refined gentleman. Hearing the doorbell, Bluto is quick to revert to professional form, and with a few quick moves, has outfitted himself in tuxedo, fancy shoes and vest. “Entree”, he greets them at the door. “I already ‘et”, retorts Popeye, misunderstanding the professor’s lingo. “I want this to become a gentleman”, Olive tells Bluto. Bluto pulls out a monocle and closely observes Popeye. “Not so good…I wonder if that thing is human”, he mutters. Bluto’s first move is to throw Popeye’s pipe away into a nearby planter, where a daisy withers from the smell of its smoke. “Hey, what’s the idea? Do ya wanna spoil the flavor?”, complains Popeye. Bluto next demonstrates the proper way to greet a lady, making a low bow, taking Olive’s hand and kissing it. “Merci Bouquet”, responds Olive. Popeye shows his own idea of how to greet a lady – unceremoniously running up to her, shaking her hand vigorously, and complimenting her with “Well shiver me timbers! You’re the trimmest little craft I ever seen.” With disdain toward Popeye, Bluto demonstrates how to escort Olive up a flight of stairs. “She was always able to walk up herself before”, mumbles Popeye. Bluto directs Popeye to escort her back down. Popeye does so by seating Olive on the staircase railing, pushing her into a rapid downhill slide, then catching her on the other end. “Voulex voulez voo, and I do mean you”, says Popeye in a bow. Bluto’s third lesson demonstrates how to put on, then remove, a lady’s wrap. Seeing the garment go on and off so quickly, Popeye asks why’d he put it on her in the first place. Bluto asks Popeye to do it. Popeye tosses the coat into the air, then tickles Olive under the arms, causing her to raise her limbs high above her head, just in time to receive the falling coat. However, removing the wrap isn’t so easy, as Popeye yanks it down instead of up, flipping Olive’s feet out from under her in a backwards pratfall. Olive is disgusted, and Bluto grabs a book of etiquette, tosses it in Popeye’s face, and tells him, “Read this, and come back in ten years!”. Popeye crashes into the opposite wall, dislodging a painting. Its frame falls off, and the canvas wraps itself around Popeye’s head in the shape of a dunce cap.

Bluto’s old instincts now kick in, and, believing the field clear, he goes on the make for Olive, trying to steal kisses, then holding her in a stranglehold when she will not comply. Popeye returns, complaining, “Hey, that ain’t eticute!” Bluto politely excuses himself, to take Popeye into the next room, where he gives Popeye a final lesson – “Two’s company, and three’s a crowd”, socking him into a wall and wedging him to it with a piano. Popeye retracts his head into his shirt collar like a turtle, producing the old-standby spinach can, which not only frees him, but briefly transforms him into an outfit of top hat, tuxedo and tails. “And he thinks he’s a gentleman”, Popeye boasts. Returning to the room where Bluto is still strangling Olive, Popeye invites Bluto back to the other office, politely opening and closing the door for the bully. As the door closes, all hell breaks loose behind the wall, which vibrates vigorously from the commotion behind it, plaster chips falling everywhere. Bluto suddenly crashes through the wall, his outfit torn and in disarray. Popeye emerges, socking him into another wall, while politely saying, “Oh, pardon me”. He bows to Olive, while delivering a rear kick to Bluto’s face with his foot. “Two’s company, and you’re a crowd”, he tells Bluto, delivering more blows, while, one by one, he places a coat on Bluto, then his hat, scarf, and walking cane, then says he’s sorry to see Bluto going, as he socks Bluto off the tower. Bluto falls to street level, bouncing off the building’s awning, and through the plate glass window of a shop on the other side of the street. There, in his battered outfit, he hangs in the store window between two mannequins, beneath a sign that says, “Suits for Hire. Fool your friends. Look Like a Gentleman. $1.00 down.” Back in the penthouse, Olive plants kisses on Popeye, as he falls back upon his old catchphrase, “I yam what I yam and that’s all wot I yam.”

Bluto’s old instincts now kick in, and, believing the field clear, he goes on the make for Olive, trying to steal kisses, then holding her in a stranglehold when she will not comply. Popeye returns, complaining, “Hey, that ain’t eticute!” Bluto politely excuses himself, to take Popeye into the next room, where he gives Popeye a final lesson – “Two’s company, and three’s a crowd”, socking him into a wall and wedging him to it with a piano. Popeye retracts his head into his shirt collar like a turtle, producing the old-standby spinach can, which not only frees him, but briefly transforms him into an outfit of top hat, tuxedo and tails. “And he thinks he’s a gentleman”, Popeye boasts. Returning to the room where Bluto is still strangling Olive, Popeye invites Bluto back to the other office, politely opening and closing the door for the bully. As the door closes, all hell breaks loose behind the wall, which vibrates vigorously from the commotion behind it, plaster chips falling everywhere. Bluto suddenly crashes through the wall, his outfit torn and in disarray. Popeye emerges, socking him into another wall, while politely saying, “Oh, pardon me”. He bows to Olive, while delivering a rear kick to Bluto’s face with his foot. “Two’s company, and you’re a crowd”, he tells Bluto, delivering more blows, while, one by one, he places a coat on Bluto, then his hat, scarf, and walking cane, then says he’s sorry to see Bluto going, as he socks Bluto off the tower. Bluto falls to street level, bouncing off the building’s awning, and through the plate glass window of a shop on the other side of the street. There, in his battered outfit, he hangs in the store window between two mannequins, beneath a sign that says, “Suits for Hire. Fool your friends. Look Like a Gentleman. $1.00 down.” Back in the penthouse, Olive plants kisses on Popeye, as he falls back upon his old catchphrase, “I yam what I yam and that’s all wot I yam.”

• Check out LEARN POLIKENESS on DailyMotion

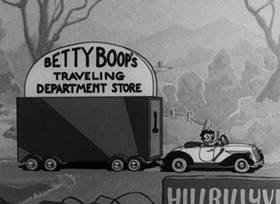

Be Up To Date (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop. 2/25/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Thomas Johnson, anim.) – A rather forgettable, by-the-numbers late installment in the Betty Boop series, with little in the way of standout gags, and very little plot. Betty arrives in the sleepy burg of “Hillbillyville”, with possibly the most memorable scene of the film being an extended panning shot of a 3D model of the community at the film’s opening, wonderfully displayed by means of Max’s turntable camera. Betty drives a spiffy convertible sedan, with a large boxy trailer in tow, labeled as Betty Boop’s Traveling Department Store. She sings an original title song, about her intentions to sell her wares to the hillbilly folk and bring them “up to date” with her new fashions, gadgets, and appliances. Indeed, the residents of the community might be in need of some livening up, as they seem to approach all of their daily tasks while essentially sound asleep. Wood is sawed by a band saw strapped between two rocking chairs, the rocking of their respective occupants accomplishing the sawing of a tree in the middle. A traffic cop, required to rotate an intersection sign between stop and go positions, has all the work performed by a wide-awake pig strapped to his ankle, who tows him into the proper position to rotate the sign. And so on. When Betty arrives in the town center, she releases the trailer, which unfolds into a canopied four-segment floor layout with several aisles and sub-wings full of goods. The unknowledgeable citizens starting buying up Betty’s wares, to utilize for all the wrong reasons. A bald man buys a mop to use as a wig. A woman buys a waffle iron, using it as a curling iron to create her own unique rectangular hairdo. One man buys an outboard motor to attach to the handle of his plow, propelling him effortlessly across the fields, as he rides upon the handle motionlessly, and still complains that he’s working himself to death. Some of the hillbillies favoring the use of shootin’ irons buy a toaster, then use the popping-up toast as targets for skeet shooting. Another woman buys a carpet sweeper, folding its handle to create an upper-story perch, and having her son use the wheeled bottom as a scooter, to transport Mom home atop the perch as a passenger seat. Then, as usual, the citizens find ways Betty’s items can be converted into use as musical instruments. Of course, musical washboards and pots and pans come as a basic. But using a pitchfork’s tines as a mouth harp? A pair of crutches as fiddle and bow? And a flit gun as a slide-whistle? The film devolves into the usual dance fest, and Betty folds up shop and leaves town, having left behind a bevy of satisfied, up to date customers.

Be Up To Date (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop. 2/25/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Thomas Johnson, anim.) – A rather forgettable, by-the-numbers late installment in the Betty Boop series, with little in the way of standout gags, and very little plot. Betty arrives in the sleepy burg of “Hillbillyville”, with possibly the most memorable scene of the film being an extended panning shot of a 3D model of the community at the film’s opening, wonderfully displayed by means of Max’s turntable camera. Betty drives a spiffy convertible sedan, with a large boxy trailer in tow, labeled as Betty Boop’s Traveling Department Store. She sings an original title song, about her intentions to sell her wares to the hillbilly folk and bring them “up to date” with her new fashions, gadgets, and appliances. Indeed, the residents of the community might be in need of some livening up, as they seem to approach all of their daily tasks while essentially sound asleep. Wood is sawed by a band saw strapped between two rocking chairs, the rocking of their respective occupants accomplishing the sawing of a tree in the middle. A traffic cop, required to rotate an intersection sign between stop and go positions, has all the work performed by a wide-awake pig strapped to his ankle, who tows him into the proper position to rotate the sign. And so on. When Betty arrives in the town center, she releases the trailer, which unfolds into a canopied four-segment floor layout with several aisles and sub-wings full of goods. The unknowledgeable citizens starting buying up Betty’s wares, to utilize for all the wrong reasons. A bald man buys a mop to use as a wig. A woman buys a waffle iron, using it as a curling iron to create her own unique rectangular hairdo. One man buys an outboard motor to attach to the handle of his plow, propelling him effortlessly across the fields, as he rides upon the handle motionlessly, and still complains that he’s working himself to death. Some of the hillbillies favoring the use of shootin’ irons buy a toaster, then use the popping-up toast as targets for skeet shooting. Another woman buys a carpet sweeper, folding its handle to create an upper-story perch, and having her son use the wheeled bottom as a scooter, to transport Mom home atop the perch as a passenger seat. Then, as usual, the citizens find ways Betty’s items can be converted into use as musical instruments. Of course, musical washboards and pots and pans come as a basic. But using a pitchfork’s tines as a mouth harp? A pair of crutches as fiddle and bow? And a flit gun as a slide-whistle? The film devolves into the usual dance fest, and Betty folds up shop and leaves town, having left behind a bevy of satisfied, up to date customers.

The film’s basic idea was remade in the 1940’s by Popeye, in “Silly Hillbilly” (1949), which will not be included in this survey.

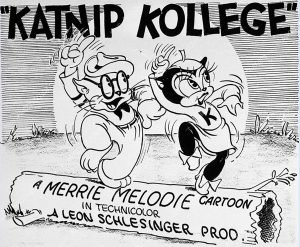

Katnip Kollege (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 6/11/38 – Cal Dalton, Cal Howard, dir.) holds a unique place in Warner carttoon history, being the only short in the series styled to closely resemble the musical shorts which the Vitaphone division of Warners had been turning out in live action for years. It is also unique in being the only Merrie Melodie to feature soundtrack portions which are directly edited from musical outtakes from the Warner feature, “Over the Goal”, featuring the uncredited vocals of Johnnie “Scat” Davis and Mabel Todd, with additional assist by the Pied Pipers.

Katnip Kollege (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 6/11/38 – Cal Dalton, Cal Howard, dir.) holds a unique place in Warner carttoon history, being the only short in the series styled to closely resemble the musical shorts which the Vitaphone division of Warners had been turning out in live action for years. It is also unique in being the only Merrie Melodie to feature soundtrack portions which are directly edited from musical outtakes from the Warner feature, “Over the Goal”, featuring the uncredited vocals of Johnnie “Scat” Davis and Mabel Todd, with additional assist by the Pied Pipers.

The scene opens at the doors of an all-cat university. The set design is rather unbelievable, as the university is depicted as built inside an old barrel, which from the outside looks only big enough to house one classroom at best, but when seen from the interior has an entire hallway of classroom doors (are we predicting Harry Potter’s traveling tents or Room of Requirement?), including one for the campus’s most popular class, Swingology, where the rhythms from within nearly vibrate the door off its hinges. Inside, the class members clap time and beat out a rhythm (with one class member whom we will meet shortly hopelessly off the beat), as the professor appears at the front of the class by means of a rising stage elevator built into the floor, performing a pecking dance step. He struts his stuff before the class’s syncopated rendition of “Good Morning to You”, with even an outline drawing of him on the blackboard dancing in step with him. Teacher begins to ask various students in rhyme to recite their homework lessons. They respond with verses of a musical history lesson, lifted from the lyrics of the song, “Let That Be a Lesson To You” from the feature, “Hollywood Hotel”. A star performance is entered by a miss Kitty Bright, the prettiest kitten in class, wearing a cute hat and monogrammed sweater. The one tomcat in a back row, one Johnnie, wearing nerd glasses, still tries desperately to clap at the same time as the rest of the class. “Now Johnnie, let’s hear your sonnets. Make them sound like Kostelanatz.” (An odd reference to Andre Kostelanatz, leader of a large orchestra which seemed to straddle the fence with light classical music only slightly flavored with modern rhythm influence.) Johnnie is a hopeless failure, as the best he can mutter is “Vo deo oh do, Charleston, a Razz a ma Tazz, and Boop Boop a Doop.” “Boy, is that corny”, says the upset professor, who calls Johnnie to the front of the class, and into the corner, where Johnnie sits on a stool, and presses a wall button that elevates his seat upwards until his head makes contact with a suspended dunce cap hanging in the corner. As the class is dismissed, various students taunt Johnnie with comments like “You swing like a rusty gate”. Kitty is the last to leave, and tosses Johnnie a pin from her sweater. “Here’s your old frat pin. You can look me up when you learn to swing.”

That night, as the moon rises, a jam session begins on the campus grounds, where the student body lounges to hear the tunes of a college combo. A glee club chimes in with lyrics about “The only use we’ve found so far for corn is when you pop it.” The band’s music wafts back to the classroom, where Johnnie still sits under the dunce cap. Johnnie notices that the pendulum of the clock on the wall is in sync with the music he is hearing, and begins to sway his head in pecking fashion to match the movements of the pendulum. Dawn finally breaks that this is the sense of timing he was lacking. “I got it! The rhythm bug bit me. La de ah!”, says Johnnie, and with a final double check that he can still match the clock movement, he zooms out the door to where the band is playing. To the surprise of all, especially Kitty, he launches into his own musical number, “As Easy As Rolling Off a Log” (the outtake from “Over the Goal”), which provides the musical setting for the remainder of the cartoon, framed as a production number duet between Johnnie and Kitty, dancing atop a log Kitty was sitting on. Johnnie climaxes with a hot trumpet solo, extending his musical talents beyond mere vocal, and the two end the number by literally falling off the log in question, with Kitty rising from behind it, covering Johnnie’s face with kisses for the iris out.

That night, as the moon rises, a jam session begins on the campus grounds, where the student body lounges to hear the tunes of a college combo. A glee club chimes in with lyrics about “The only use we’ve found so far for corn is when you pop it.” The band’s music wafts back to the classroom, where Johnnie still sits under the dunce cap. Johnnie notices that the pendulum of the clock on the wall is in sync with the music he is hearing, and begins to sway his head in pecking fashion to match the movements of the pendulum. Dawn finally breaks that this is the sense of timing he was lacking. “I got it! The rhythm bug bit me. La de ah!”, says Johnnie, and with a final double check that he can still match the clock movement, he zooms out the door to where the band is playing. To the surprise of all, especially Kitty, he launches into his own musical number, “As Easy As Rolling Off a Log” (the outtake from “Over the Goal”), which provides the musical setting for the remainder of the cartoon, framed as a production number duet between Johnnie and Kitty, dancing atop a log Kitty was sitting on. Johnnie climaxes with a hot trumpet solo, extending his musical talents beyond mere vocal, and the two end the number by literally falling off the log in question, with Kitty rising from behind it, covering Johnnie’s face with kisses for the iris out.

All’s Fair At the Fair (Fleischer/Paramount, Color Classic, 8/26/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Myron Waldman, Graham Place, anim.) – Taking direct inspiration from the forthcoming World’s Fair being constructed in New York, Fleischer presents his own Fair to end all Fairs (with no specific locale disclosed). An old rural couple (arriving in horse-drawn carriage) are brought up-to-date with exhibits of modern technology. First they take advantage of the free parking, leaving their wagon. A large crane with a powerful U-shaped magnet piles cars high, one atop another, by pulling them upwards and placing them into stacks. But the wagon, having no metal, won’t rise. So, the ends of the magnet adapt into a pair of clamps, seizing the horse and wagon bodily to place them in position atop a pile. Maw and Paw view many assembly-line gadgets, including an automatic sheep-shearing machine turning out finished sweaters; a pair of wood-cutting machines, one that pinches out finished chairs and furniture from a log by means of king-size cookie cutters, and another that whittles down a whole log into a single clothespin’ and self-building homes that merely require pouring wood and nails into a house-shaped mold, shake well, and out comes the completed structure. Robots play a part in an imposing structure with neon sign announcing “Shave – Haircut – Dining – Dancing”. Paw chooses the shave and haircut – all administered step by step by female robot attendants, while Maw undergoes an assembly-line makeover, including a figure-mold that compresses her like an iron maiden to put curves back into her physique. When the robots are through. Maw and Paw not only look 30 years younger, but hardly recognize each other.

All’s Fair At the Fair (Fleischer/Paramount, Color Classic, 8/26/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Myron Waldman, Graham Place, anim.) – Taking direct inspiration from the forthcoming World’s Fair being constructed in New York, Fleischer presents his own Fair to end all Fairs (with no specific locale disclosed). An old rural couple (arriving in horse-drawn carriage) are brought up-to-date with exhibits of modern technology. First they take advantage of the free parking, leaving their wagon. A large crane with a powerful U-shaped magnet piles cars high, one atop another, by pulling them upwards and placing them into stacks. But the wagon, having no metal, won’t rise. So, the ends of the magnet adapt into a pair of clamps, seizing the horse and wagon bodily to place them in position atop a pile. Maw and Paw view many assembly-line gadgets, including an automatic sheep-shearing machine turning out finished sweaters; a pair of wood-cutting machines, one that pinches out finished chairs and furniture from a log by means of king-size cookie cutters, and another that whittles down a whole log into a single clothespin’ and self-building homes that merely require pouring wood and nails into a house-shaped mold, shake well, and out comes the completed structure. Robots play a part in an imposing structure with neon sign announcing “Shave – Haircut – Dining – Dancing”. Paw chooses the shave and haircut – all administered step by step by female robot attendants, while Maw undergoes an assembly-line makeover, including a figure-mold that compresses her like an iron maiden to put curves back into her physique. When the robots are through. Maw and Paw not only look 30 years younger, but hardly recognize each other.

The seemingly rejuvenated couple next enter a dance hall. A tin-can styled robot is seated at a piano, with a coin slot in back. Paw deposits a coin, and not only does the robot play, but multiple unmanned instruments connected to air hoses and hydraulics mounted around the piano begin an accompaniment, amounting to a Latin number resembling Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers’ “Carioca”. Spying a pair of doors with sign above reading “Dancing Partners”, the couple deposit more coins in the doors, and out sway a shapely female robot and a tall suave male robot, who each partner up with the couple for an extended and well choreographed dance number. One move in the number again breaks into the Truckin’ craze, and Paw ad libs a lyric playing on another then-current hit, “The Flat Foot Floogie”. repeating, “Flat foot farmer and a plow plow” instead of “Flat foot floogie with a floy floy”. Time runs out on the dancing partners, who return to their respective cabinets – but Paw and Maw now know the new step, and dance entirely well on their own. As they exit the exhibit, they happen upon a coin operated machine at the gate, labeled, “Autos”. Paw inserts another coin, and a small package about the size of the palm of his hand pops out of the vending machine. Paw unfolds it – into a full-size automobile, complete with rumble seat to accommodate their horse, and the three happily speed off down the road toward home.

The seemingly rejuvenated couple next enter a dance hall. A tin-can styled robot is seated at a piano, with a coin slot in back. Paw deposits a coin, and not only does the robot play, but multiple unmanned instruments connected to air hoses and hydraulics mounted around the piano begin an accompaniment, amounting to a Latin number resembling Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers’ “Carioca”. Spying a pair of doors with sign above reading “Dancing Partners”, the couple deposit more coins in the doors, and out sway a shapely female robot and a tall suave male robot, who each partner up with the couple for an extended and well choreographed dance number. One move in the number again breaks into the Truckin’ craze, and Paw ad libs a lyric playing on another then-current hit, “The Flat Foot Floogie”. repeating, “Flat foot farmer and a plow plow” instead of “Flat foot floogie with a floy floy”. Time runs out on the dancing partners, who return to their respective cabinets – but Paw and Maw now know the new step, and dance entirely well on their own. As they exit the exhibit, they happen upon a coin operated machine at the gate, labeled, “Autos”. Paw inserts another coin, and a small package about the size of the palm of his hand pops out of the vending machine. Paw unfolds it – into a full-size automobile, complete with rumble seat to accommodate their horse, and the three happily speed off down the road toward home.

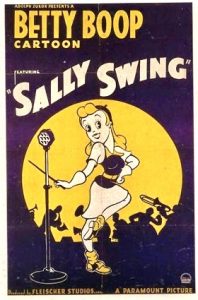

Sally Swing (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 10/14/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/Gordon Sheehan, anim.) – A lively musical outing for the series, although Betty herself definitely plays second fiddle to the uncredited guest artist – none other than Rose Marie (later of fame on Dick Van Dyke and the Hollywood Squares), no longer a “Baby”, but still able to scat a mean swing number. (As noted by previous commentary on this website, this cartoon was intended to be the swan song for Betty, and the introduction of Sally as her new cartoon successor – but the plans for further episodes never materialized.) In the hall of science of a prestigious university, Betty Boop, a faculty member, maintains a private examination room. However, this day she is not conducting tests or grading exams. She is deep in thought with a couple of student body leaders over rounding up the talent to perform at a big dance to be held on campus. While the two students are in agreement with her that the act they need is a musical aggregation, they are both strictly squares, and their efforts to jazz up “Good Night, Ladies” just fail to put Betty into the groove. Betty pulls a lever behind her desk, activating a carpet to act as an early version of George Jetson’s traveling sidewalks, ushering the singer out the door, where he stumbles on a bar of soap left on the floor by a cleaning lady in the corridor, and makes a surprise hasty exit from the building. Betty looks over other student talent prospects in her outer waiting room. They are all out of step with the times or the theme of the evening, none of them showing any potential for swing (including a wanna-be Joe Penner type who wants to know if Betty wants to buy a duck, a ventriloquist with a dummy who sounds like Charlie McCarthy, and a pair of vaudevilian types who perform a Russian dance climaxed by the phrase, “Good Evening, Friends”). The situation looks hopeless, and Betty dismisses all the wanna-bes, and paces the floor in her inner office to try to get an idea where to find a swing band leader.

Sally Swing (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 10/14/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/Gordon Sheehan, anim.) – A lively musical outing for the series, although Betty herself definitely plays second fiddle to the uncredited guest artist – none other than Rose Marie (later of fame on Dick Van Dyke and the Hollywood Squares), no longer a “Baby”, but still able to scat a mean swing number. (As noted by previous commentary on this website, this cartoon was intended to be the swan song for Betty, and the introduction of Sally as her new cartoon successor – but the plans for further episodes never materialized.) In the hall of science of a prestigious university, Betty Boop, a faculty member, maintains a private examination room. However, this day she is not conducting tests or grading exams. She is deep in thought with a couple of student body leaders over rounding up the talent to perform at a big dance to be held on campus. While the two students are in agreement with her that the act they need is a musical aggregation, they are both strictly squares, and their efforts to jazz up “Good Night, Ladies” just fail to put Betty into the groove. Betty pulls a lever behind her desk, activating a carpet to act as an early version of George Jetson’s traveling sidewalks, ushering the singer out the door, where he stumbles on a bar of soap left on the floor by a cleaning lady in the corridor, and makes a surprise hasty exit from the building. Betty looks over other student talent prospects in her outer waiting room. They are all out of step with the times or the theme of the evening, none of them showing any potential for swing (including a wanna-be Joe Penner type who wants to know if Betty wants to buy a duck, a ventriloquist with a dummy who sounds like Charlie McCarthy, and a pair of vaudevilian types who perform a Russian dance climaxed by the phrase, “Good Evening, Friends”). The situation looks hopeless, and Betty dismisses all the wanna-bes, and paces the floor in her inner office to try to get an idea where to find a swing band leader.

Suddenly, the answer comes to her as if by a miracle. In the inner corridor of the building, Betty sees through the glass door of her office the silhouette of the cleaning woman, gently scatting a tune to herself, and moving with the steps of a jitterbug while she cleans the glass panel of Betty’s door. Betty runs outside, grabs the girl by the hand, and ushers her inside as just the person she needs. “What have you been doing scrubbing? You should be cleaning up!” says Betty in excited mile-a-minute dialogue. Telephoning the student body president, Boop says she has someone she knows the students will love. The scene neatly dissolves to the night of the big dance, with Betty, as mistress of ceremonies, continuing her praise and introduction of her new find over the stage microphone to the entire student body. The cleaning woman has been spruced up in a jazzy new outfit and long flowing hair, and has been dubbed by Betty, “Sally Swing”. Before a bandstand containing a newly organized student orchestra, the microphone is turned over to Sally, and she cuts loose with a snappy theme song, low growling scat vocals, and energetic dancing. The band is inspired by her energy and tempo, and the clarinetist begins to play so “red hot” that his instrument catches fire, and has to be doused in a bucket of water. The audience also loves her, and dances wildly to her beat, while Betty claps out time from the wings, and encourages Sally to “knock ‘em in the aisles.” The Dean, watching from a private table in the back of the hall, is the only sour face in the room. He believes the abandon has gone too far, and calls for everyone to stop. “I am the principal, and it’s against my principles”, he shouts to no avail, being drowned out by the music. He makes his way up on stage, but being so close to Sally’s gyrations and pecking, he involuntarily finds himself copying her movements – until he can’t help himself, and is taken with the rhythm too. Betty joins them both on stage, and the three perform some precision unison dance moves together, until someone tosses up to the stage a cap and gown, which land on Sally, making her an honorary graduate with a major in music, for the iris out.

Suddenly, the answer comes to her as if by a miracle. In the inner corridor of the building, Betty sees through the glass door of her office the silhouette of the cleaning woman, gently scatting a tune to herself, and moving with the steps of a jitterbug while she cleans the glass panel of Betty’s door. Betty runs outside, grabs the girl by the hand, and ushers her inside as just the person she needs. “What have you been doing scrubbing? You should be cleaning up!” says Betty in excited mile-a-minute dialogue. Telephoning the student body president, Boop says she has someone she knows the students will love. The scene neatly dissolves to the night of the big dance, with Betty, as mistress of ceremonies, continuing her praise and introduction of her new find over the stage microphone to the entire student body. The cleaning woman has been spruced up in a jazzy new outfit and long flowing hair, and has been dubbed by Betty, “Sally Swing”. Before a bandstand containing a newly organized student orchestra, the microphone is turned over to Sally, and she cuts loose with a snappy theme song, low growling scat vocals, and energetic dancing. The band is inspired by her energy and tempo, and the clarinetist begins to play so “red hot” that his instrument catches fire, and has to be doused in a bucket of water. The audience also loves her, and dances wildly to her beat, while Betty claps out time from the wings, and encourages Sally to “knock ‘em in the aisles.” The Dean, watching from a private table in the back of the hall, is the only sour face in the room. He believes the abandon has gone too far, and calls for everyone to stop. “I am the principal, and it’s against my principles”, he shouts to no avail, being drowned out by the music. He makes his way up on stage, but being so close to Sally’s gyrations and pecking, he involuntarily finds himself copying her movements – until he can’t help himself, and is taken with the rhythm too. Betty joins them both on stage, and the three perform some precision unison dance moves together, until someone tosses up to the stage a cap and gown, which land on Sally, making her an honorary graduate with a major in music, for the iris out.

NEXT WEEK: The war looms ahead – not to mention the zoot suit, with the reet pleat – till then, Have a Merry Christmas!