As the 1950’s draw to a close and the ‘60‘s begin, we find a greater predominance of baseball-related films coming from the Paramount studios in New York, which contributes over half of the footage reviewed today. This is probably the result of the continuing fame of the Yankees, if not other New York teams, of which the Paramount staffers were no doubt aware. Two more entries are placed into the roster by Walter Lantz, and some brief references also from Warner and Disney. The climax of the action is a memorable routine that transcended mediums from comedy record to film, providing Paramount with its last extended-length short, and the audience with an intriguing viewpoint upon the game never previously conceptualized

With apologies for a chronological oversight, our first two offerings backtrack somewhat from where we left off last week. Which is Witch (Paramount/Famous, Casper, 5/2/58 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) is the odd (and only) appearance on the big-screen of comics’ creation, Wendy, the Good Little Witch. The Paramount animators don’t yet appear to know what to do with her, failing to give her any opportunity to use magic, failing to include the three hags she normally lives with, and avoiding except for a handful of introductory shots any sign of her trademark red robes. Instead, they quickly have her change into a two-piece bathing suit, making her virtually unrecognizable as Wendy, but more of a blonde Little Audrey. Whether from lack of audience reaction, writer inspiration, or sheer time (considering rights to the Casper series would be swallowed up shortly thereafter by Harvey Comics), there would be no theatrical follow-ups. Only when the studio was re-contracted to produce new animation for Harvey’s “The New Casper Cartoon Show” on TV in the 1960’s did Wendy finally stick to her comic-book look and magic tricks – the Harvey owners making sure this time that they got it right.

With apologies for a chronological oversight, our first two offerings backtrack somewhat from where we left off last week. Which is Witch (Paramount/Famous, Casper, 5/2/58 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) is the odd (and only) appearance on the big-screen of comics’ creation, Wendy, the Good Little Witch. The Paramount animators don’t yet appear to know what to do with her, failing to give her any opportunity to use magic, failing to include the three hags she normally lives with, and avoiding except for a handful of introductory shots any sign of her trademark red robes. Instead, they quickly have her change into a two-piece bathing suit, making her virtually unrecognizable as Wendy, but more of a blonde Little Audrey. Whether from lack of audience reaction, writer inspiration, or sheer time (considering rights to the Casper series would be swallowed up shortly thereafter by Harvey Comics), there would be no theatrical follow-ups. Only when the studio was re-contracted to produce new animation for Harvey’s “The New Casper Cartoon Show” on TV in the 1960’s did Wendy finally stick to her comic-book look and magic tricks – the Harvey owners making sure this time that they got it right.

Spooky, invisible along with Casper, is playing a little catch between them with a baseball, en route to the local sandlot. Casper is in an odd, forgetful mood today, as, after going to all the trouble of accompanying Spooky to the playing field, he “balks” at going inside, suddenly remembering he has a date with Wendy. Spooky grumbles at being left in the lurch, and calls all girls “joy killers”, angrily tossing the ball against the ground, only to get bonked with it on the rebound. (Ghosts are such odd creatures. The first time Casper played catch in “The Friendly Ghost”, the ball went right through his chest. Yet he was somehow able to pick it up, and toss it back. Do ghosts only become solid enough to move objects when they want to? And if so, then why would Spooky leave himself solid enough to receive an injuring blow to the head?)

Spooky, invisible along with Casper, is playing a little catch between them with a baseball, en route to the local sandlot. Casper is in an odd, forgetful mood today, as, after going to all the trouble of accompanying Spooky to the playing field, he “balks” at going inside, suddenly remembering he has a date with Wendy. Spooky grumbles at being left in the lurch, and calls all girls “joy killers”, angrily tossing the ball against the ground, only to get bonked with it on the rebound. (Ghosts are such odd creatures. The first time Casper played catch in “The Friendly Ghost”, the ball went right through his chest. Yet he was somehow able to pick it up, and toss it back. Do ghosts only become solid enough to move objects when they want to? And if so, then why would Spooky leave himself solid enough to receive an injuring blow to the head?)

The scene changes to Wendy’s home. As mentioned, the writers don’t get her living companions right, instead having her share an old house with another child-witch named (what else) Hazel, who at least gets to demonstrate some magic by flying off on her own broom (complete with stick shift). Casper arrives, and carries all the beach gear for the day while Wendy switches into bathing suit. Spooky vows to “crab” the romance, first by slipping a live crab into the beach umbrella, to drop in front of Wendy for a surprise. Wendy rolls out a picnic blanket, and places a layer cake in its center. Spooky dives into the sand, coming up under the blanket to flip the cake onto Wendy’s head, then drops the blanket over Casper so that he’ll appear to have been the practical joker. Casper tries to make amends by helping Wendy dive for shells to add to her collection. Spooky consumes a bottle of ink to blacken himself, then dives into the water, assuming the shape of an octopus. After frightening Wendy, he spits out the ink upon Casper, leaving him to again be blamed for the joke in view of his darkened appearance. Wendy gives Casper a final ultimatum of no more tricks, or she’ll go home. Spooky spoils a motorboat ride by misdirecting the rudder from underwater, causing the boat to crash. Wendy leaves in a huff, but Casper finds Spooky still hanging on to the motor, and Spooky confesses his motive to get Casper back to the ball game. Casper follows Wendy home, and tries to explain it was Spooky all the time – until Spooky makes clear that Casper is right, by hollering for Casper to come out and play ball. Instead, Wendy sends Witch Hazel to pinch hit for Casper, and show the smarty up. Spooky pitches a ball to Hazel, and Hazel socks it for a long hit into the outfield. Hazel begins flying the bases upon her broomstick, reaching one leg down as she passes over each bag to properly tag each base. Spooky is running into the outfield with his mitt, but misses a direct catch, forcing him to catch up with the ball on a bounce, and try to outrace Hazel back to the plate. It looks like Spooky will win the race, as he stands at the plate with outstretched arm, ready to make the tag. But Hazel goes into a slide, obscuring the scene with a cloud of dust. When the dust clears, Spooky is still standing with the ball outreached toward the baseline as we previously found him, but Hazel is nowhere to be seen. Spooky looks back over his shoulder, as the camera pans right, to find Hazel now behind Spooky, having somehow avoided the ball and slid right through the ghost’s body. Not only that, she picked up home plate along the way, which she has pulled about two feet to the rear of Spooky’s toes, and now stands on herself, calling herself “Safe!” Spooky renews his classification of girls as “joy killers”, and flings the ball sharply against the ground – of course, taking another rebound from the ball smack upon his head, for the fade out.

The scene changes to Wendy’s home. As mentioned, the writers don’t get her living companions right, instead having her share an old house with another child-witch named (what else) Hazel, who at least gets to demonstrate some magic by flying off on her own broom (complete with stick shift). Casper arrives, and carries all the beach gear for the day while Wendy switches into bathing suit. Spooky vows to “crab” the romance, first by slipping a live crab into the beach umbrella, to drop in front of Wendy for a surprise. Wendy rolls out a picnic blanket, and places a layer cake in its center. Spooky dives into the sand, coming up under the blanket to flip the cake onto Wendy’s head, then drops the blanket over Casper so that he’ll appear to have been the practical joker. Casper tries to make amends by helping Wendy dive for shells to add to her collection. Spooky consumes a bottle of ink to blacken himself, then dives into the water, assuming the shape of an octopus. After frightening Wendy, he spits out the ink upon Casper, leaving him to again be blamed for the joke in view of his darkened appearance. Wendy gives Casper a final ultimatum of no more tricks, or she’ll go home. Spooky spoils a motorboat ride by misdirecting the rudder from underwater, causing the boat to crash. Wendy leaves in a huff, but Casper finds Spooky still hanging on to the motor, and Spooky confesses his motive to get Casper back to the ball game. Casper follows Wendy home, and tries to explain it was Spooky all the time – until Spooky makes clear that Casper is right, by hollering for Casper to come out and play ball. Instead, Wendy sends Witch Hazel to pinch hit for Casper, and show the smarty up. Spooky pitches a ball to Hazel, and Hazel socks it for a long hit into the outfield. Hazel begins flying the bases upon her broomstick, reaching one leg down as she passes over each bag to properly tag each base. Spooky is running into the outfield with his mitt, but misses a direct catch, forcing him to catch up with the ball on a bounce, and try to outrace Hazel back to the plate. It looks like Spooky will win the race, as he stands at the plate with outstretched arm, ready to make the tag. But Hazel goes into a slide, obscuring the scene with a cloud of dust. When the dust clears, Spooky is still standing with the ball outreached toward the baseline as we previously found him, but Hazel is nowhere to be seen. Spooky looks back over his shoulder, as the camera pans right, to find Hazel now behind Spooky, having somehow avoided the ball and slid right through the ghost’s body. Not only that, she picked up home plate along the way, which she has pulled about two feet to the rear of Spooky’s toes, and now stands on herself, calling herself “Safe!” Spooky renews his classification of girls as “joy killers”, and flings the ball sharply against the ground – of course, taking another rebound from the ball smack upon his head, for the fade out.

Right Off the Bat (Paramount, Modern Madcap, 11/7/58 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.). Here’s a cartoon you aren’t likely to see circulating on TV these days. In fact, though its date and would indicate that it should have been included in the standard package of theatrical Casper cartoons that first appeared on “Matty’s Funday Funnies” and then made wide syndication on local stations, I have never encountered a broadcast of it in any known market. The reason becomes immediately obvious from the first shot – a baseball team known as the “Redskins”. (Though this somehow didn’t affect local stations’ airings of an earlier, seemingly better-natured Noveltoon entitled “Slip Me Some Redskin”.) To compound this, a principal character in the plot is the team’s “scout” – a full-blooded American Indian, depicted in all the sterotype manner Hollywood was capable of, including bright-red complexion and broken-English dialect fresh out of the teepee. Many other cartoons have been pulled from the air for such reasons – but this one seems somehow to severely press the taboo buttons in a manner that is more glaring than funny, not being salvaged by the type of redeeming comedy that somehow continues to get old Warner classics like “Wagon Heels” or “Slightly Daffy” occasional screenings.

Right Off the Bat (Paramount, Modern Madcap, 11/7/58 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.). Here’s a cartoon you aren’t likely to see circulating on TV these days. In fact, though its date and would indicate that it should have been included in the standard package of theatrical Casper cartoons that first appeared on “Matty’s Funday Funnies” and then made wide syndication on local stations, I have never encountered a broadcast of it in any known market. The reason becomes immediately obvious from the first shot – a baseball team known as the “Redskins”. (Though this somehow didn’t affect local stations’ airings of an earlier, seemingly better-natured Noveltoon entitled “Slip Me Some Redskin”.) To compound this, a principal character in the plot is the team’s “scout” – a full-blooded American Indian, depicted in all the sterotype manner Hollywood was capable of, including bright-red complexion and broken-English dialect fresh out of the teepee. Many other cartoons have been pulled from the air for such reasons – but this one seems somehow to severely press the taboo buttons in a manner that is more glaring than funny, not being salvaged by the type of redeeming comedy that somehow continues to get old Warner classics like “Wagon Heels” or “Slightly Daffy” occasional screenings.

The Redskins (whose regular lineup and manager at least are of white complexion and do not follow the stereotype) are in a hole. Their batters seem to have a knack of guiding every ball they clout right into the waiting glove of some eager fielder or baseman, for a quick and easy out. When one batter finally gets a ball past the infield, he takes time out between third base and home to film an endorsement for a brand of razor blades (a knowing joke upon the Gillette company’s heavy participation of the day in baseball advertising), claiming that the blades always give him the desired smooth-looking face when he is called out – a call which quickly follows as he slides into home massively behind the tag of the ball. The fans in the stands are calling for the Redskins to go back to the reservation, and for the team to get themselves a new manager. The team owner reminds the manager that tomorrow’s game will decide if the team is eliminated from pennant contention. The owner promises that if the game is lost, the manager will be sent back to the bush leagues.

The Redskins (whose regular lineup and manager at least are of white complexion and do not follow the stereotype) are in a hole. Their batters seem to have a knack of guiding every ball they clout right into the waiting glove of some eager fielder or baseman, for a quick and easy out. When one batter finally gets a ball past the infield, he takes time out between third base and home to film an endorsement for a brand of razor blades (a knowing joke upon the Gillette company’s heavy participation of the day in baseball advertising), claiming that the blades always give him the desired smooth-looking face when he is called out – a call which quickly follows as he slides into home massively behind the tag of the ball. The fans in the stands are calling for the Redskins to go back to the reservation, and for the team to get themselves a new manager. The team owner reminds the manager that tomorrow’s game will decide if the team is eliminated from pennant contention. The owner promises that if the game is lost, the manager will be sent back to the bush leagues.

Desperate for some sort of solution, the manager remembers he has not heard today from his “scout”. The really-red Indian referenced above is called in to the locker room, and claims he has been scouting the world’s greatest baseball player. The scout calls in one Rube Clodhopper – a full-grown horse, standing erect on hind legs in a baseball outfit. The manager, in shock and outrage, demands the horse be thrown out, but the scout insists that you throw out horse, you throw out pennant. He and the talking horse remind the manager of the important achievements horses have contributed to the history of humankind. Paul Revere’s ride. The Pony Express. And who won all those football games for Knute Rockne? Why, the Four Horsemen! The manager reluctantly sees that he has no choice but to try this wild idea, though muttering to himself that the minute the sportswriters see this, they’ll think he’s losing his marbles.

Desperate for some sort of solution, the manager remembers he has not heard today from his “scout”. The really-red Indian referenced above is called in to the locker room, and claims he has been scouting the world’s greatest baseball player. The scout calls in one Rube Clodhopper – a full-grown horse, standing erect on hind legs in a baseball outfit. The manager, in shock and outrage, demands the horse be thrown out, but the scout insists that you throw out horse, you throw out pennant. He and the talking horse remind the manager of the important achievements horses have contributed to the history of humankind. Paul Revere’s ride. The Pony Express. And who won all those football games for Knute Rockne? Why, the Four Horsemen! The manager reluctantly sees that he has no choice but to try this wild idea, though muttering to himself that the minute the sportswriters see this, they’ll think he’s losing his marbles.

The manager and scout spend the night attempting to smuggle the horse into a swank hotel for evening lodgings, though having to boost him up to an upper-story suite on a scaffold as a fake window washer, and having to make excuses for his room-service call for a bale of hay (the manager claiming that just before going to bed, he eats like a horse). Game Day finally arrives. Bottom of the ninth, needing a run, and two batters typically called out. The scout has been trying all afternoon to get the manager to put the horse in the fame, but the manger has been simply too embarrassed to let anyone see his new star. Now, with only one out left to work with, he is left with no choice but to send the horse in. As Rube trots onto the field, the eyes of the umpire and opposing team pop in bewilderment. The umpire tries to eject the horse from the game, but the scout places a rule book in front of him, and challenges him to find a rule prohibiting the horse’s play. The umpire pulls out a pair of high-power reading glasses, and carefully scans the book page by page, then, reaching the end of the volume, can only respond, “Play ball!” Rube steps up to the plate, and looks like he is going to become another Mighty Casey, refusing to swing at the first two pitches, claiming they are either too high or too low, despite the umpire calling them strikes. Finally, Rube decides the third pitch is to his liking, and smashes it with a mighty swing. An outfielder raises his glove in attempt to catch it, but his glove is driven right off his wrist by the impact of the speeding sphere. There is still enough power in the ball’s speed to propel the loose glove deep into its own hole within the outfield grass, ball and glove disappearing from sight. The outfielder is left with the task of attempting to dig for the glove and ball with his bare hands, while the crowd’s cheers fill the rafters of the stadium. But the manager turns, to find that the reasons for the crowd’s cheers may be a bit premature in the making. Rube is still standing calmly at the plate, smiling and bowing to the appreciative crowd, but otherwise not moving. “Run, for Pete’s sake, RUN!!” shouts the manager. “Well, dog my britches”, responds Rube in hayseed dialect, still not moving a muscle. “If’n I could run, I’d be in the Kentucky Derby.” We leave the ball park by way of cross-dissolve, and find ourselves on a city street in the middle of the night, following the manager pursuing the scout at full run (possibly upon a road leading back to the bush leagues), with the manager making wild periodic swings at the scout with a bat. The scout tries to verbally dissuade the manager from committing intended injury upon his person, insisting that he has the sport’s next baseball find – a buffalo!

The manager and scout spend the night attempting to smuggle the horse into a swank hotel for evening lodgings, though having to boost him up to an upper-story suite on a scaffold as a fake window washer, and having to make excuses for his room-service call for a bale of hay (the manager claiming that just before going to bed, he eats like a horse). Game Day finally arrives. Bottom of the ninth, needing a run, and two batters typically called out. The scout has been trying all afternoon to get the manager to put the horse in the fame, but the manger has been simply too embarrassed to let anyone see his new star. Now, with only one out left to work with, he is left with no choice but to send the horse in. As Rube trots onto the field, the eyes of the umpire and opposing team pop in bewilderment. The umpire tries to eject the horse from the game, but the scout places a rule book in front of him, and challenges him to find a rule prohibiting the horse’s play. The umpire pulls out a pair of high-power reading glasses, and carefully scans the book page by page, then, reaching the end of the volume, can only respond, “Play ball!” Rube steps up to the plate, and looks like he is going to become another Mighty Casey, refusing to swing at the first two pitches, claiming they are either too high or too low, despite the umpire calling them strikes. Finally, Rube decides the third pitch is to his liking, and smashes it with a mighty swing. An outfielder raises his glove in attempt to catch it, but his glove is driven right off his wrist by the impact of the speeding sphere. There is still enough power in the ball’s speed to propel the loose glove deep into its own hole within the outfield grass, ball and glove disappearing from sight. The outfielder is left with the task of attempting to dig for the glove and ball with his bare hands, while the crowd’s cheers fill the rafters of the stadium. But the manager turns, to find that the reasons for the crowd’s cheers may be a bit premature in the making. Rube is still standing calmly at the plate, smiling and bowing to the appreciative crowd, but otherwise not moving. “Run, for Pete’s sake, RUN!!” shouts the manager. “Well, dog my britches”, responds Rube in hayseed dialect, still not moving a muscle. “If’n I could run, I’d be in the Kentucky Derby.” We leave the ball park by way of cross-dissolve, and find ourselves on a city street in the middle of the night, following the manager pursuing the scout at full run (possibly upon a road leading back to the bush leagues), with the manager making wild periodic swings at the scout with a bat. The scout tries to verbally dissuade the manager from committing intended injury upon his person, insisting that he has the sport’s next baseball find – a buffalo!

A few final notes on the production. Neither the studio nor Win Sharples saw fit to waste time, money or effort composing a musical score for this one. Sharples instead falls back upon stock recordings from past cartoons for occasional musical backdrop. The use of such cut-ins is quite evident, several cues given away by abrupt volume fade-ours in mid-bar as a scene ends, and in one instance by an abrupt cut from score to total silence. However, one stellar aspect of the audio is the voice work of Sid Raymond as the long-suffering manager. His reads have a naturalness to them unusual for Paramount cartoons, which at times makes him seem to be truly living the role he is depicting. Perhaps he’d witnessed enough non-Yankees games in New York to share the emotions of losing managers, watching their pennant dreams go up in smoke.

A few final notes on the production. Neither the studio nor Win Sharples saw fit to waste time, money or effort composing a musical score for this one. Sharples instead falls back upon stock recordings from past cartoons for occasional musical backdrop. The use of such cut-ins is quite evident, several cues given away by abrupt volume fade-ours in mid-bar as a scene ends, and in one instance by an abrupt cut from score to total silence. However, one stellar aspect of the audio is the voice work of Sid Raymond as the long-suffering manager. His reads have a naturalness to them unusual for Paramount cartoons, which at times makes him seem to be truly living the role he is depicting. Perhaps he’d witnessed enough non-Yankees games in New York to share the emotions of losing managers, watching their pennant dreams go up in smoke.

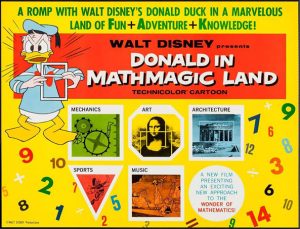

Donald in Mathemagic Land (Disney, Donald Duck (2-reel special), 6/26/59 – Hamilton Liske, dir.) – An odd film to find among cartoons upon the subject topic – but perhaps not as odd as the title may first suggest. This short’s purposes are decidedly educational, though the film received a theatrical release before becoming part of frequent classroom curriculum. (Presumably, it may still show up in classroom settings, as a DVD release of the short was offered in a special educator’s edition with additional materials for handout in the schoolroom.) A large part of the film’s overall message is that “You can find mathematics in the darndest places.” There are a few moments of lighter humor and entertainment, as explorer Donald, dressed in hunting gear as if seeking to stalk big game in Africa, encounters this strange and uncharted land, where trees grow with square roots, pencil birds out of Alice in Wonderland scribble tracks of numbers on the ground, and more numbers wash down a stream from a waterfall, colliding with rocks in the river bed and being mathematically divided into smaller numbers. A voice (Paul Frees) addresses Donald from the ether, declaring itself to be the True Spirit of Adventure”. Donald is all for adventure, but unconvinced that a trip into the wonders of mathematics is how to achieve it. “That’s for eggheads”. Donald declares. The spirit sets out to prove him wrong, demonstrating through time-travelling and transformational journeys that things Donald loves wouldn’t exist had it not been for mathematics. Among these is a journey to ancient Greece, to meet Pythagorus and his combo of “eggheads” for the mathematical creation of the musical scale. Also included is an extended survey of sports, demonstrating geometrical shapes incorporated into the games’ design (including, of course, the baseball diamond) or play techniques that require the calculation of moves (such as cushion billiards shots, or the complex moves of chessmen). Donald is finally convinced that there’s more to mathematics than two-plus-two. Donald is shown a long and endless corridor of doors, each one concealing some new and amazing discovery. Donald eagerly uses his new-found mathematical appreciation to open door after door, but finally reaches a series of doors which are firmly locked. The spirit informs him that these are the doors of future discovery, and the key to their eventual unlocking is of course, as Donald now guesses, mathematics. The film ends with the spirit’s quote from Galileo: “Mathematics is the alphabet with which God has written the universe.”

Donald in Mathemagic Land (Disney, Donald Duck (2-reel special), 6/26/59 – Hamilton Liske, dir.) – An odd film to find among cartoons upon the subject topic – but perhaps not as odd as the title may first suggest. This short’s purposes are decidedly educational, though the film received a theatrical release before becoming part of frequent classroom curriculum. (Presumably, it may still show up in classroom settings, as a DVD release of the short was offered in a special educator’s edition with additional materials for handout in the schoolroom.) A large part of the film’s overall message is that “You can find mathematics in the darndest places.” There are a few moments of lighter humor and entertainment, as explorer Donald, dressed in hunting gear as if seeking to stalk big game in Africa, encounters this strange and uncharted land, where trees grow with square roots, pencil birds out of Alice in Wonderland scribble tracks of numbers on the ground, and more numbers wash down a stream from a waterfall, colliding with rocks in the river bed and being mathematically divided into smaller numbers. A voice (Paul Frees) addresses Donald from the ether, declaring itself to be the True Spirit of Adventure”. Donald is all for adventure, but unconvinced that a trip into the wonders of mathematics is how to achieve it. “That’s for eggheads”. Donald declares. The spirit sets out to prove him wrong, demonstrating through time-travelling and transformational journeys that things Donald loves wouldn’t exist had it not been for mathematics. Among these is a journey to ancient Greece, to meet Pythagorus and his combo of “eggheads” for the mathematical creation of the musical scale. Also included is an extended survey of sports, demonstrating geometrical shapes incorporated into the games’ design (including, of course, the baseball diamond) or play techniques that require the calculation of moves (such as cushion billiards shots, or the complex moves of chessmen). Donald is finally convinced that there’s more to mathematics than two-plus-two. Donald is shown a long and endless corridor of doors, each one concealing some new and amazing discovery. Donald eagerly uses his new-found mathematical appreciation to open door after door, but finally reaches a series of doors which are firmly locked. The spirit informs him that these are the doors of future discovery, and the key to their eventual unlocking is of course, as Donald now guesses, mathematics. The film ends with the spirit’s quote from Galileo: “Mathematics is the alphabet with which God has written the universe.”

Kiddie League (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 11/3/59 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – You could never tell Woody Woodpecker’s precise age – or whether we were being shown incidents from his life that sometimes projected back in time. In most episodes, he appeared presumably full-grown, obviously at maturity in “Born to Peck”, old-enough to be dating (“Real Gone Woody”) or to marry (“A Fine Feathered Frenzy”), and to have a juvenile nephew and niece (“Get Lost”). Yet, in his final appearance theatrically, “Bye Bye Blackboard”, he was only of grammar school age. And, in this episode, we find him as a participant in a little league baseball game! Maybe the rule books and school admission policies are silent upon the subject of woodpeckers, and their age doesn’t matter to qualify them for inclusion.

Kiddie League (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 11/3/59 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – You could never tell Woody Woodpecker’s precise age – or whether we were being shown incidents from his life that sometimes projected back in time. In most episodes, he appeared presumably full-grown, obviously at maturity in “Born to Peck”, old-enough to be dating (“Real Gone Woody”) or to marry (“A Fine Feathered Frenzy”), and to have a juvenile nephew and niece (“Get Lost”). Yet, in his final appearance theatrically, “Bye Bye Blackboard”, he was only of grammar school age. And, in this episode, we find him as a participant in a little league baseball game! Maybe the rule books and school admission policies are silent upon the subject of woodpeckers, and their age doesn’t matter to qualify them for inclusion.

A little league world series game is scheduled between the Woody Woodpeckers and the Bubble Gummers. Both names don’t quite fit, as Woody is the only woodpecker on his team, and his own catcher seems to be the one using bubble gum, blowing bubbles with the name of the pitch he desires written on them. The primary players for the Bubble Gummers are a pipsqueak still in diapers (or rather, trying to be, as the diaper keeps falling down arond his ankles), and a huge, fat, overgrown kid named Chester (who would make one subsequent appearance to better advantage the following year, as spoiled brat Reginald in the semi-classic, “The Bird Who Came To Dinner”). A stadium announcer emphasizes the friendly atmosphere of good sportsmanship that prevails throughout the stadium, as beaming parents respond neighborly even to the parents of their child’s opponents. To round things out, Willoughby, the little Droopy-like man with the big moustache (who had not yet been cast as a police inspector), serves as umpire.

A little league world series game is scheduled between the Woody Woodpeckers and the Bubble Gummers. Both names don’t quite fit, as Woody is the only woodpecker on his team, and his own catcher seems to be the one using bubble gum, blowing bubbles with the name of the pitch he desires written on them. The primary players for the Bubble Gummers are a pipsqueak still in diapers (or rather, trying to be, as the diaper keeps falling down arond his ankles), and a huge, fat, overgrown kid named Chester (who would make one subsequent appearance to better advantage the following year, as spoiled brat Reginald in the semi-classic, “The Bird Who Came To Dinner”). A stadium announcer emphasizes the friendly atmosphere of good sportsmanship that prevails throughout the stadium, as beaming parents respond neighborly even to the parents of their child’s opponents. To round things out, Willoughby, the little Droopy-like man with the big moustache (who had not yet been cast as a police inspector), serves as umpire.

Woody’s catcher signals for a curve. Woody delivers one that skywrites the word “curve” in the air. The little diaper boy hits one that bounces back and forth on both sides of Woody, forcing him to make a throw to first base. A more-observant umpire might call the play runner interference, as the diaper boy’s slide into a dust cloud seems to beat the throw by a mile, but the dust clears to reveal the runner stopped face-first by the upraised sole of the baseman’s shoe, having bever reached the base for the tag. Willoughby calls the runner out, and is conked on the head by a pop bottle thrown by the kid’s father. Willoughby calmly walks over to the father’s seat, then judo-flips the dad by the wrist right and left, adding that if he doesn’t behave himself, he will be asked to leave. Chester comes up to bat, and socks the ball but good with his oversized strength, but not quite outside the park. Chester begins running, but is already tiring from his overweight condition as he rounds first base. By second base, he is panting. Third base sees hm dragging. He can’t even generate speed enough for a slide into home, and finally places a hand upon the plate unopposed, via a slow crawl. After all this, Willoughby calls, “Foul ball!” Chester’s Mom appears, and conks Willoughby on the head with the handle of an umbrella. His moustache now frazzled, Willoughby changes his call. “Well, it was kinda fair.” Now the crowd in general boos him, and he is buried among a pile of thrown seat cushions and pop bottles.

Woody’s catcher signals for a curve. Woody delivers one that skywrites the word “curve” in the air. The little diaper boy hits one that bounces back and forth on both sides of Woody, forcing him to make a throw to first base. A more-observant umpire might call the play runner interference, as the diaper boy’s slide into a dust cloud seems to beat the throw by a mile, but the dust clears to reveal the runner stopped face-first by the upraised sole of the baseman’s shoe, having bever reached the base for the tag. Willoughby calls the runner out, and is conked on the head by a pop bottle thrown by the kid’s father. Willoughby calmly walks over to the father’s seat, then judo-flips the dad by the wrist right and left, adding that if he doesn’t behave himself, he will be asked to leave. Chester comes up to bat, and socks the ball but good with his oversized strength, but not quite outside the park. Chester begins running, but is already tiring from his overweight condition as he rounds first base. By second base, he is panting. Third base sees hm dragging. He can’t even generate speed enough for a slide into home, and finally places a hand upon the plate unopposed, via a slow crawl. After all this, Willoughby calls, “Foul ball!” Chester’s Mom appears, and conks Willoughby on the head with the handle of an umbrella. His moustache now frazzled, Willoughby changes his call. “Well, it was kinda fair.” Now the crowd in general boos him, and he is buried among a pile of thrown seat cushions and pop bottles.

Even though it’s still the first inning, Chester comes to bat again. It seems like there should be an out, as the ball appears to be caught by a baseman, leaping out of his pants into the air for the catch. But Chester continues to round the bases, this time with more energy than before, tipping his hat to the crowd. However, Woody works hard with a shovel at home plate, digging a deep pit where the plate should be. Chester falls in, and as he climbs back out, Woody tags him with the ball. Willoughby confirms it as an out, and when Chester protests, Willoughby socks him waist deep into the ground, insisting, “You’re out, sonny.” Now, the bottim half of the inning, with Woody at bat. Two strikes register on Woody, as the diapered catcher keeps running out in front of Woody to catch the ball. Woody prevents a third repetition, by tying the catcher up in a knot inside his own diaper. Chester delivers his slow-slow ball. It is a typical classic slow-motion floater, and Willoughby asks Woody if he’d like to go home and come back later. Woody yawns, and states no, he’ll wait it out. Woody pays with a yo-yo, and engages in small talk with Willoughby as to how the members of their respective families are. Finally, Willoughby alerts Woody, “I believe this is your ball coming.” “So it is”, says Woody, stretching, and finally gets a chance to sock it, with the usual result of punching a hole through Chester’s mitt and palm. As Woofy runs the bases, Chester quotes his motto: “If at first you don’t succeed, CHEAT!” He pulls out a pistol, which perhaps isn’t loaded with live ammunition, but has the effect of a light-gun in one of those old shooting gallery settings, where a shot will cause the mechanical bear to reverse direction. Woody is hit by the invisible beam several times, with the sound of a loud arcade bell-clang, and begins walking mechanically and reversing direction with each shot. Somehow, Chester runs out of ammunition, with only the sounds of empty clicks from his gun. Woody happens at this point to be heading in the right direction toward home, and mechanically trots over the plate, scoring a run. The distraught Chester turns the pistol to his own temple, and fires. But instead of live ammo or a beam of light, all that emerges from the gun’s barrel is a stream of water – as it inexplicably reverts to water-pistol mode.

Even though it’s still the first inning, Chester comes to bat again. It seems like there should be an out, as the ball appears to be caught by a baseman, leaping out of his pants into the air for the catch. But Chester continues to round the bases, this time with more energy than before, tipping his hat to the crowd. However, Woody works hard with a shovel at home plate, digging a deep pit where the plate should be. Chester falls in, and as he climbs back out, Woody tags him with the ball. Willoughby confirms it as an out, and when Chester protests, Willoughby socks him waist deep into the ground, insisting, “You’re out, sonny.” Now, the bottim half of the inning, with Woody at bat. Two strikes register on Woody, as the diapered catcher keeps running out in front of Woody to catch the ball. Woody prevents a third repetition, by tying the catcher up in a knot inside his own diaper. Chester delivers his slow-slow ball. It is a typical classic slow-motion floater, and Willoughby asks Woody if he’d like to go home and come back later. Woody yawns, and states no, he’ll wait it out. Woody pays with a yo-yo, and engages in small talk with Willoughby as to how the members of their respective families are. Finally, Willoughby alerts Woody, “I believe this is your ball coming.” “So it is”, says Woody, stretching, and finally gets a chance to sock it, with the usual result of punching a hole through Chester’s mitt and palm. As Woofy runs the bases, Chester quotes his motto: “If at first you don’t succeed, CHEAT!” He pulls out a pistol, which perhaps isn’t loaded with live ammunition, but has the effect of a light-gun in one of those old shooting gallery settings, where a shot will cause the mechanical bear to reverse direction. Woody is hit by the invisible beam several times, with the sound of a loud arcade bell-clang, and begins walking mechanically and reversing direction with each shot. Somehow, Chester runs out of ammunition, with only the sounds of empty clicks from his gun. Woody happens at this point to be heading in the right direction toward home, and mechanically trots over the plate, scoring a run. The distraught Chester turns the pistol to his own temple, and fires. But instead of live ammo or a beam of light, all that emerges from the gun’s barrel is a stream of water – as it inexplicably reverts to water-pistol mode.

The ninth inning, and the announcer confusingly announces that the Woodpeckers are leading 1 to nothing. (What happened to Chester’s “kinda-fair ball”? This was long before the call could be reversed from New York. And what happened to all the other batters that came to the plate between Chester’s two at-bats in the first inning?) There isn’t even the element of suspense as Woody steps to the plate – since his was obviously the home team in pitching first, the game should already be over with Woody’s team ahead! Yet, as in Popeye’s “The Twisker Pitcher”, the bottom of the ninth is played anyway, even though the game is possibly already won. Woody hits one out of the park, and Chester attempts to perform the old Bugs Bunny catch of the ball upon a tall building’s flagpole. To complicate and stretch things, Chester realizes as he stands upon the flagpole that he forgot his glove, and runs all the way back to the stadium to retrieve it, then all the way back to the flagpole again. He extends his arm as the ball finally comes down – and bounces out of his mitt. Chester begins wailing like a baby – but the incident still isn’t over yet. Back at the stadium, and viewing the play through a telescope, Willoughby once again calls “Foul ball!” This time, Wiloughby can’t be right, as we saw the ball fly over Chester’s head at the pitcher’s mound. At least half the crowd (those who are supporters of the Bubble Gummers) know it, and arguments begin between the occupants of adjoining seats in the stands with the parents and supporters of the Woodpeckers. Willoughby himself is again buried in cushions and pop bottles, while fistfights break out in the bleachers in an utter riot. The sportscaster tries to wrap up the broadcast, while flying objects intrude upon the announcer’s booth, causing him to periodically duck, as he says: “And so ends another friendly game, to promote neighborly love – sportsmanship – good will – HELLLPP!!”

The ninth inning, and the announcer confusingly announces that the Woodpeckers are leading 1 to nothing. (What happened to Chester’s “kinda-fair ball”? This was long before the call could be reversed from New York. And what happened to all the other batters that came to the plate between Chester’s two at-bats in the first inning?) There isn’t even the element of suspense as Woody steps to the plate – since his was obviously the home team in pitching first, the game should already be over with Woody’s team ahead! Yet, as in Popeye’s “The Twisker Pitcher”, the bottom of the ninth is played anyway, even though the game is possibly already won. Woody hits one out of the park, and Chester attempts to perform the old Bugs Bunny catch of the ball upon a tall building’s flagpole. To complicate and stretch things, Chester realizes as he stands upon the flagpole that he forgot his glove, and runs all the way back to the stadium to retrieve it, then all the way back to the flagpole again. He extends his arm as the ball finally comes down – and bounces out of his mitt. Chester begins wailing like a baby – but the incident still isn’t over yet. Back at the stadium, and viewing the play through a telescope, Willoughby once again calls “Foul ball!” This time, Wiloughby can’t be right, as we saw the ball fly over Chester’s head at the pitcher’s mound. At least half the crowd (those who are supporters of the Bubble Gummers) know it, and arguments begin between the occupants of adjoining seats in the stands with the parents and supporters of the Woodpeckers. Willoughby himself is again buried in cushions and pop bottles, while fistfights break out in the bleachers in an utter riot. The sportscaster tries to wrap up the broadcast, while flying objects intrude upon the announcer’s booth, causing him to periodically duck, as he says: “And so ends another friendly game, to promote neighborly love – sportsmanship – good will – HELLLPP!!”

Unnatural History (Warner, 11/14/59 – Robert McKimson, dir.) – A collection of random spot-gags regarding animals, returning to the format style Tex Avery introduced in the late 1930’s. The particular sequence of interest for our present purposes shows us a dog owner in the office of the Hick Towne theatrical booking agency, attempting to show off an allegedly-talking dog. The canine, however, seems to have a very limited and mundane vocabulary, in which every supposedly-uttered word sounds more like a standard dog bark, and has to be interpreted to the agent by the dog’s master. “What covers a house?” “Roof.” “See, he said roof. What’s my name?” “Ralph.” “See, he said Ralph. Who was the greatest baseball player? “Ruth.” “See, he said Ruth.” The agent has had enough, and kicks both dog and owner out on their ear. The dog rises, brushes himself off, and apologetically inquires to the owner, “Maybe I shoulda said, ‘Di Maggio’?”

Unnatural History (Warner, 11/14/59 – Robert McKimson, dir.) – A collection of random spot-gags regarding animals, returning to the format style Tex Avery introduced in the late 1930’s. The particular sequence of interest for our present purposes shows us a dog owner in the office of the Hick Towne theatrical booking agency, attempting to show off an allegedly-talking dog. The canine, however, seems to have a very limited and mundane vocabulary, in which every supposedly-uttered word sounds more like a standard dog bark, and has to be interpreted to the agent by the dog’s master. “What covers a house?” “Roof.” “See, he said roof. What’s my name?” “Ralph.” “See, he said Ralph. Who was the greatest baseball player? “Ruth.” “See, he said Ruth.” The agent has had enough, and kicks both dog and owner out on their ear. The dog rises, brushes himself off, and apologetically inquires to the owner, “Maybe I shoulda said, ‘Di Maggio’?”

• Watch UNNATURAL HISTORY on DailyMotion – CLICK HERE!

Fish Hooked (Lantz/Universal, Chilly Willy, 9/7/60 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – One might in some ways view this episode as the beginning of the end for this series. Although it is written in traditional manner for Chilly to act only in pantomime, this would mark director Smith’s first encounter with the series since the original pilot “Chilly Willy” from 1953, which featured a different design for the character lifted from Dick Lundy’s “The Sliphorn King of Polaroo”, and a markedly different personality for the penguin, talk-singing in falsetto tones. Smith was unfamiliar with working with the characters of Chilly and Smedly as honed and fine-tuned by Tex Avery and Alex Lovy. As Lovy was leaving the studio, Smith was called upon to pinch-hit for this one, leaving his usual comfort zone of Woody Woodpecker cartoons until a replacement for the director’s chair could be found for the penguin, ultimately in the form of Jack Hannah and subsequently Sid Marcus. Smith’s direction on this film is, to say the best, routine, and lacking in the substantial zing of timing of his predecessors. Plus, he seems to make no effort to generate from the writing staff a decent ending for the story, letting the whole episode fall flat at the end without a socko gag or punch line. Smith would not work on the series again until 1966, at which time he became Lantz’s sole-remaining director, transforming Chilly into a sometimes dialogue-laden talking character, and doing his progressive best to run the series into the ground.

Fish Hooked (Lantz/Universal, Chilly Willy, 9/7/60 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – One might in some ways view this episode as the beginning of the end for this series. Although it is written in traditional manner for Chilly to act only in pantomime, this would mark director Smith’s first encounter with the series since the original pilot “Chilly Willy” from 1953, which featured a different design for the character lifted from Dick Lundy’s “The Sliphorn King of Polaroo”, and a markedly different personality for the penguin, talk-singing in falsetto tones. Smith was unfamiliar with working with the characters of Chilly and Smedly as honed and fine-tuned by Tex Avery and Alex Lovy. As Lovy was leaving the studio, Smith was called upon to pinch-hit for this one, leaving his usual comfort zone of Woody Woodpecker cartoons until a replacement for the director’s chair could be found for the penguin, ultimately in the form of Jack Hannah and subsequently Sid Marcus. Smith’s direction on this film is, to say the best, routine, and lacking in the substantial zing of timing of his predecessors. Plus, he seems to make no effort to generate from the writing staff a decent ending for the story, letting the whole episode fall flat at the end without a socko gag or punch line. Smith would not work on the series again until 1966, at which time he became Lantz’s sole-remaining director, transforming Chilly into a sometimes dialogue-laden talking character, and doing his progressive best to run the series into the ground.

The setting is Oceanland Aquarium, including a large central tank in the style of California’s Marineland of the Pacific with all varieties of fish, both large and small. (One notable gag has a swordfish etching with his nose upon the chest of an opponent a Z, in the mark of Zorro.) Smedly is in charge of the porpoise show, but seems to be having his share of trouble feeding them fish from a high platform. The jumping porpoise keeps latching onto Smedly’s outstretched arm as well as the fish held by it, and takes Smedly down with him into the water on each try. Meanwhile, Chilly is spotted, sitting on the tank’s perimeter railing with a rod and reel, and hooking himself free meals out of the giant fish bowl. Smedly interrupts his show to remind Chilly of the signs warning to check all fishing tackle at desk, and tosses Chilly off the property, far into the ocean. However, within a matter of moments, Chilly is back, leaping in place of the porpoise to grab more free fish right out of Smedly’s hand, and politely tipping his hat in a “thank you” before he descends back into the water. Smedly reappears with a new fish, but holding a baseball bat behind his back. Chilly gets the fish again, and Smedly misses him with a few wild swings of the bat. Smedly now assumes the pose of a professional, with bat held high off his shoulder, and states. “That boy don’t know it, but he’s messin’ around with a old ball player. Next time, I‘ll just bat him over left field fence.” Chilly rises from the water again, but this time, to Smedly’s surprise, armed with a baseball. Chilly winds up, and slams a pitch at close range, right into Smedly’s left eye. As Chilly descends to the safety of the tank again, Smedly, the ball still caught in his eye, remarks to the camera, “Mighty good fast ball that boy’s got.”

The setting is Oceanland Aquarium, including a large central tank in the style of California’s Marineland of the Pacific with all varieties of fish, both large and small. (One notable gag has a swordfish etching with his nose upon the chest of an opponent a Z, in the mark of Zorro.) Smedly is in charge of the porpoise show, but seems to be having his share of trouble feeding them fish from a high platform. The jumping porpoise keeps latching onto Smedly’s outstretched arm as well as the fish held by it, and takes Smedly down with him into the water on each try. Meanwhile, Chilly is spotted, sitting on the tank’s perimeter railing with a rod and reel, and hooking himself free meals out of the giant fish bowl. Smedly interrupts his show to remind Chilly of the signs warning to check all fishing tackle at desk, and tosses Chilly off the property, far into the ocean. However, within a matter of moments, Chilly is back, leaping in place of the porpoise to grab more free fish right out of Smedly’s hand, and politely tipping his hat in a “thank you” before he descends back into the water. Smedly reappears with a new fish, but holding a baseball bat behind his back. Chilly gets the fish again, and Smedly misses him with a few wild swings of the bat. Smedly now assumes the pose of a professional, with bat held high off his shoulder, and states. “That boy don’t know it, but he’s messin’ around with a old ball player. Next time, I‘ll just bat him over left field fence.” Chilly rises from the water again, but this time, to Smedly’s surprise, armed with a baseball. Chilly winds up, and slams a pitch at close range, right into Smedly’s left eye. As Chilly descends to the safety of the tank again, Smedly, the ball still caught in his eye, remarks to the camera, “Mighty good fast ball that boy’s got.”

The film goes roughly downhill from there. Smedly is ultimately forced to drain the tank to get at Chilly. He empties it via a drainpipe, piling beached fish high, which Chilly attempts to carry away in one large pile. But Smedly finally takes the fish away, and picks up Chilly in a small fish net. However, Smedly quickly finds himself in a net, thanks to a passing dog-catcher, who notes that Smedly doesn’t have a license. A belabored stretch of dialogue has Smedly claiming he is not a dog, as he has a job and can talk. But all the dog catcher has to do is meow like a cat, and Smedly starts reflexively barking, causing him to be carted away in the catcher’s truck, as he confesses to the camera that sometimes he forgets that he is a dog. How funny is this idea? Not very. And all Chilly does is put on a dining bib, and go back to the aquarium. (Didn’t they just drain the tank anyway? What’s left for dessert?)

The film goes roughly downhill from there. Smedly is ultimately forced to drain the tank to get at Chilly. He empties it via a drainpipe, piling beached fish high, which Chilly attempts to carry away in one large pile. But Smedly finally takes the fish away, and picks up Chilly in a small fish net. However, Smedly quickly finds himself in a net, thanks to a passing dog-catcher, who notes that Smedly doesn’t have a license. A belabored stretch of dialogue has Smedly claiming he is not a dog, as he has a job and can talk. But all the dog catcher has to do is meow like a cat, and Smedly starts reflexively barking, causing him to be carted away in the catcher’s truck, as he confesses to the camera that sometimes he forgets that he is a dog. How funny is this idea? Not very. And all Chilly does is put on a dining bib, and go back to the aquarium. (Didn’t they just drain the tank anyway? What’s left for dessert?)

Another look at education is Kozmo Goes to School (Paramount, Noveltoon, November, 1961) – Seymour Kneitel, dir.). Kozmo is just your average kid – if you happen to live in another galaxy. Green in complexion, with a wiggly line for a mouth, Kozmo can always be found in a glass helmet and miniature space suit, his trusty all-purpose ray gun at the ready. He travels down to Earth in his flying saucer for a visit every so often, just for kicks, but always with good intentions to be helpful where he can. Not quite Casper, but at least there’s some basic goodness rather than malice in his heart.

Another look at education is Kozmo Goes to School (Paramount, Noveltoon, November, 1961) – Seymour Kneitel, dir.). Kozmo is just your average kid – if you happen to live in another galaxy. Green in complexion, with a wiggly line for a mouth, Kozmo can always be found in a glass helmet and miniature space suit, his trusty all-purpose ray gun at the ready. He travels down to Earth in his flying saucer for a visit every so often, just for kicks, but always with good intentions to be helpful where he can. Not quite Casper, but at least there’s some basic goodness rather than malice in his heart.

Kozmo’s ship lands in an open field, and he pops out for his usual random look around. The first thing he sights is a bulldog chasing and cornering a defenseless kitty kat against a fence. Kozmo doesn’t think bullying is right, and focuses his ray gun on the cat, transforming it into a giant three times the size of the bulldog. The pursued becomes the pursuer, and all is well in Kozmo’s eyes. Ultimately, however, Kozmo encounters a man who needs no help, and is in no friendly mood. He is a truant officer, and insists that Kozmo should be in school. He takes hold of Kozmo’s hand, and leads him toward the schoolhouse, not noticing that Kozmo isn’t walking, but floating weightless behind the officer. “All you kids are alike”, mutters the officer, “playing spaceman instead of learning your A B C’s.”

At the school, a bully is having his fun during study period. He produces from his desk a turtle, and sends it creeping forward under the row of desks ahead of him, with a lit candle placed upon its back, to give all the other students in the row an instant hotfoot. The suspicious teacher calls upon him to solve a math problem of 2 + 3. The bully nervously counts his digits, mutters about carrying numbers to the next column, and groans, “Why does she always have to give me the tough ones?” In the door marches the truant officer with Kozmo. “Since you’ve missed this morning’s arithmetic lesson, do you think you can do this problem?”, she demands. Kozmo activates his jet boosters, hovering in front of the blackboard, and writes a series of mathematical sub-calculations that Wernher Von Braun would be proud of, correctly making final arrival at the number 5. The teacher is impressed, and allows Kozmo to take a seat at the head of the class. “Why dat big show off. Nobody’s gonna be smarter than me”, vows the bully, taking aim at Kozmo’s helmet with a slingshot. But Kozmo spots him before he can fire, and whips out his ray gun. Firing a heat beam, he aims at the hand of the bully holding the handle of the slingshot. “Yeow!”. yells the bully, letting go of the handle. The device is pulled backwards from the retraction of the stretched rubber, popping itself inside the bully’s mouth, propping it open like a large letter Y. The bully tosses a plate at Kozmo, but Kozmo ducks, then again uses the ray gun to divert it, picking up upon it a bottle of ink from the teacher’s desk, and sending it back to spill upon the bully’s head. The bully swears to get the little guy at recess, and, pulling out a peashooter, makes sure recess comes early, by shooting a flow of peas at the classroom alarm bell.

At the school, a bully is having his fun during study period. He produces from his desk a turtle, and sends it creeping forward under the row of desks ahead of him, with a lit candle placed upon its back, to give all the other students in the row an instant hotfoot. The suspicious teacher calls upon him to solve a math problem of 2 + 3. The bully nervously counts his digits, mutters about carrying numbers to the next column, and groans, “Why does she always have to give me the tough ones?” In the door marches the truant officer with Kozmo. “Since you’ve missed this morning’s arithmetic lesson, do you think you can do this problem?”, she demands. Kozmo activates his jet boosters, hovering in front of the blackboard, and writes a series of mathematical sub-calculations that Wernher Von Braun would be proud of, correctly making final arrival at the number 5. The teacher is impressed, and allows Kozmo to take a seat at the head of the class. “Why dat big show off. Nobody’s gonna be smarter than me”, vows the bully, taking aim at Kozmo’s helmet with a slingshot. But Kozmo spots him before he can fire, and whips out his ray gun. Firing a heat beam, he aims at the hand of the bully holding the handle of the slingshot. “Yeow!”. yells the bully, letting go of the handle. The device is pulled backwards from the retraction of the stretched rubber, popping itself inside the bully’s mouth, propping it open like a large letter Y. The bully tosses a plate at Kozmo, but Kozmo ducks, then again uses the ray gun to divert it, picking up upon it a bottle of ink from the teacher’s desk, and sending it back to spill upon the bully’s head. The bully swears to get the little guy at recess, and, pulling out a peashooter, makes sure recess comes early, by shooting a flow of peas at the classroom alarm bell.

At recess, the bully tries to horn in upon every activity Kozmo tries. First, the swings, knocking Kozmo off the seat, and insisting that Kozmo push him if he knows what’s good for him. Kozmo pushes with his ray gun – in fact, so far as to place the bully upside down above the swing set, as high as its support chains will allow. Then Kozmo lets jim fall, straight down upon the swing set framework, bending the metal rods into the shape of the bully silhouette. Next, football. The bully again pushes Kozmo away from the ball, insisting he himself will kick off. Kozmo sets his ray to a setting worthy of an alchemist, which transforms the leather ball into one of solid steel. “OWW!!” yells the bully, as he nearly fractures his foot, to the laughter of his fellow classmates. Finally. Kozmo tries baseball, but the bully grabs the bat away to take a swing at the pitcher’s best pitch. The nervous pitcher throws, but Kozmo is ever at the ready with his rays, and disintegrates the ball just as it reaches home plate, leaving the bully to uncork his mightiest swing at absolutely nothing. The force of the swing drives him like a corkscrew into a crater four feet deep, as the class breaks into hilarious laughter again. The bully can’t stand being a laughing stock, and confronts the entire class, fists raised, stating that they need to be taught a lesson. Well, we know how Kozmo feels about a big guy picking on a little guy. So things turn full circle, as Kozmo resets his ray to the same setting with which he started the picture – the growth ray. Within a second, he has turned the ray upon everyone in the class except the bully, who all grow about five grades in height, leaving the bully as the new runt of the class. “Now, now, take it easy, fellas”, says the bully, cringing from what’s coming. As class resumes, the bully is seen with two black eyes, while the teacher marvels at the sudden growth spurt of the rest of the class. As for Kozmo, there is an empty chair, and a student catches sight at the window of a strange craft heading for outer space. Kozmo’s visiting time is over for now, as he heads back to his home planet, until his next adventure.

At recess, the bully tries to horn in upon every activity Kozmo tries. First, the swings, knocking Kozmo off the seat, and insisting that Kozmo push him if he knows what’s good for him. Kozmo pushes with his ray gun – in fact, so far as to place the bully upside down above the swing set, as high as its support chains will allow. Then Kozmo lets jim fall, straight down upon the swing set framework, bending the metal rods into the shape of the bully silhouette. Next, football. The bully again pushes Kozmo away from the ball, insisting he himself will kick off. Kozmo sets his ray to a setting worthy of an alchemist, which transforms the leather ball into one of solid steel. “OWW!!” yells the bully, as he nearly fractures his foot, to the laughter of his fellow classmates. Finally. Kozmo tries baseball, but the bully grabs the bat away to take a swing at the pitcher’s best pitch. The nervous pitcher throws, but Kozmo is ever at the ready with his rays, and disintegrates the ball just as it reaches home plate, leaving the bully to uncork his mightiest swing at absolutely nothing. The force of the swing drives him like a corkscrew into a crater four feet deep, as the class breaks into hilarious laughter again. The bully can’t stand being a laughing stock, and confronts the entire class, fists raised, stating that they need to be taught a lesson. Well, we know how Kozmo feels about a big guy picking on a little guy. So things turn full circle, as Kozmo resets his ray to the same setting with which he started the picture – the growth ray. Within a second, he has turned the ray upon everyone in the class except the bully, who all grow about five grades in height, leaving the bully as the new runt of the class. “Now, now, take it easy, fellas”, says the bully, cringing from what’s coming. As class resumes, the bully is seen with two black eyes, while the teacher marvels at the sudden growth spurt of the rest of the class. As for Kozmo, there is an empty chair, and a student catches sight at the window of a strange craft heading for outer space. Kozmo’s visiting time is over for now, as he heads back to his home planet, until his next adventure.

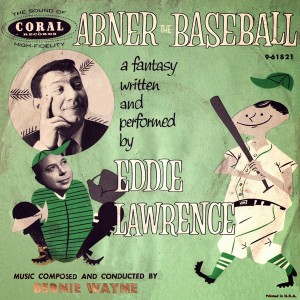

Abner the Baseball (Paramount, 11/61 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – The executives funding the output of the Paramount cartoon studio weren’t about to reverse themselves as to their decision to drastically cut the animation budget, forcing the studio to work in highly-stylized and rigid animation in a flat mock-UPA style. However, in an effort to inject some new life into their tiring storylines and overworked stock-cast of voice actors, they were willing to spring for a new face to provide both voice-overs and writing talent to the product. Enter Eddie Lawrence, a comedian specializing in comic monologues, who had recently made a claim to fame with a series of reasonable-selling comedy recordings for Coral Records, particularly in the guise of a persona he called “The Old Philosopher”. These routines would involve him asking the listeners, in a sort of littlish-voice that perhaps owed a bit to Bill Thompson’s style of speech for Droopy, about whether they had ever experienced various forms of comic mishaps, each such situation described in a manner calculated to include a preliminary punch-line, then summing up the discussion with the catch-phrase, “Is that your problem, Bunky?” Then, he would suddenly transform in voice to a bold and brash flag-waving style of pep-up speech, as a mock-motivational speaker, so insistent in tone as to be intent on leaving the listener no choice but to shape-up according to his standards, while patriotic-style music would pound-out a cadence in the background. Paramount never chose to directly adapt the Philosopher into an animated character, but incorporated the two split-personality personas of this routine into a pair of clashing characters who would become “Swifty and Shorty”, Shorty incorporating the little voice and humble demeanor, while tall and lean Swifty acquired the brash and forceful style of the monologue’s wrap-ups, sometimes even lapsing into trying to kick-start Shorty’s patriotic sensibilities to do things the way Swifty wants, as in attempting to force him into embarking on a physical fitness program in “Fizzicle Fizzle”.

Abner the Baseball (Paramount, 11/61 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – The executives funding the output of the Paramount cartoon studio weren’t about to reverse themselves as to their decision to drastically cut the animation budget, forcing the studio to work in highly-stylized and rigid animation in a flat mock-UPA style. However, in an effort to inject some new life into their tiring storylines and overworked stock-cast of voice actors, they were willing to spring for a new face to provide both voice-overs and writing talent to the product. Enter Eddie Lawrence, a comedian specializing in comic monologues, who had recently made a claim to fame with a series of reasonable-selling comedy recordings for Coral Records, particularly in the guise of a persona he called “The Old Philosopher”. These routines would involve him asking the listeners, in a sort of littlish-voice that perhaps owed a bit to Bill Thompson’s style of speech for Droopy, about whether they had ever experienced various forms of comic mishaps, each such situation described in a manner calculated to include a preliminary punch-line, then summing up the discussion with the catch-phrase, “Is that your problem, Bunky?” Then, he would suddenly transform in voice to a bold and brash flag-waving style of pep-up speech, as a mock-motivational speaker, so insistent in tone as to be intent on leaving the listener no choice but to shape-up according to his standards, while patriotic-style music would pound-out a cadence in the background. Paramount never chose to directly adapt the Philosopher into an animated character, but incorporated the two split-personality personas of this routine into a pair of clashing characters who would become “Swifty and Shorty”, Shorty incorporating the little voice and humble demeanor, while tall and lean Swifty acquired the brash and forceful style of the monologue’s wrap-ups, sometimes even lapsing into trying to kick-start Shorty’s patriotic sensibilities to do things the way Swifty wants, as in attempting to force him into embarking on a physical fitness program in “Fizzicle Fizzle”.

The original recording was released as a single in 1958.

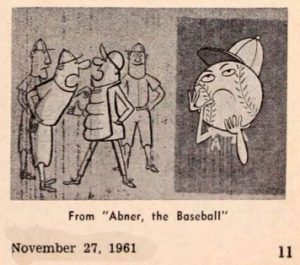

Publicity for “Abner The Baseball” in BOXOFFICE magazine, 1961

We are introduced to Abner (who talks in Lawrence’s “small” voice) in a glass display case in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. He tells a little bit about what baseballs are made of and how they’re supposed to be made “livelier” in the past few years so that more home runs can be hit. “This we could do without”, admits Abner, talking about how they bang you, toss you around, and many of them spend years after being socked over the fence being pocketed by excited kids and poked around the sandlot until they go punchy. “Brutal”, he describes it. He pities friends who have met such fate, stating that it’s worse than a golf ball. A golf ball gets hit in the rough, and then they can’t find you. A lot of the golfers don’t even want to find them. However, he points out that he’s one of the lucky ones. Yes, he got clouted over the fence, but he still has all his stitching. He begins to unfurl his tale of how he got here, and we flash back to a game at Yankee Stadium. The last of a four-game series against the Chicago White Sox. (The record version instead references the Cleveland Indians.) Abner has been in the ball sack for two days, along with 50-odd other balls, all trying to shove their way to the bottom and wait for the Kansas City Athletics coming in tomorrow. (The Athletics seem to have been the current “weak” team of the league, while in the record version, reference was to the Washington Senators.) Last of the ninth, Chicago ahead 6 to 3, Yogi Berra at bat. Suddenly, Abner is lifted from the bag, and disappears into blackness. He finds himself in the umpire’s back picket, with the ump’s garage key digging into the “L” in American League on his tender horsehide. Abner manages a glimpse of the crowd through the fabric of the umpire’s blue-serge pants (which was wearing mighty thin). He hears a trio of “bleacher bums” shouting for Yogi to blast the brains out of his erstwhile friend Sol the Ball, held in the grasp of the pitcher. One fan viciously shouts. “Tear the cover off of that ball!” Abner interjects his own thought. “Can you imagine someone tearing your skin off? Think it over, folks.”

We are introduced to Abner (who talks in Lawrence’s “small” voice) in a glass display case in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. He tells a little bit about what baseballs are made of and how they’re supposed to be made “livelier” in the past few years so that more home runs can be hit. “This we could do without”, admits Abner, talking about how they bang you, toss you around, and many of them spend years after being socked over the fence being pocketed by excited kids and poked around the sandlot until they go punchy. “Brutal”, he describes it. He pities friends who have met such fate, stating that it’s worse than a golf ball. A golf ball gets hit in the rough, and then they can’t find you. A lot of the golfers don’t even want to find them. However, he points out that he’s one of the lucky ones. Yes, he got clouted over the fence, but he still has all his stitching. He begins to unfurl his tale of how he got here, and we flash back to a game at Yankee Stadium. The last of a four-game series against the Chicago White Sox. (The record version instead references the Cleveland Indians.) Abner has been in the ball sack for two days, along with 50-odd other balls, all trying to shove their way to the bottom and wait for the Kansas City Athletics coming in tomorrow. (The Athletics seem to have been the current “weak” team of the league, while in the record version, reference was to the Washington Senators.) Last of the ninth, Chicago ahead 6 to 3, Yogi Berra at bat. Suddenly, Abner is lifted from the bag, and disappears into blackness. He finds himself in the umpire’s back picket, with the ump’s garage key digging into the “L” in American League on his tender horsehide. Abner manages a glimpse of the crowd through the fabric of the umpire’s blue-serge pants (which was wearing mighty thin). He hears a trio of “bleacher bums” shouting for Yogi to blast the brains out of his erstwhile friend Sol the Ball, held in the grasp of the pitcher. One fan viciously shouts. “Tear the cover off of that ball!” Abner interjects his own thought. “Can you imagine someone tearing your skin off? Think it over, folks.”

A first strike is called. Though property of Yankee Stadium, Abner chants quietly in favor of this, noting to the audience that “When you’re a baseball, you root for both pitchers.” But the peace is not long to last, as Sol is blasted out of the park by Yogi. Abner can’t precisely see what happened, but has the unavoidable feeling that Sol is not long for this ball park – “and neither was I.” Abner emerges into the sunlight, as the umpire tosses him to the catcher. During a meeting at the mound to discuss how to address the next batter, the catcher roughs Abner up within his mitt so much, Abner wonders if he’s been dinged already and will be taken out of the game. No such luck. Instead, he gets tossed around the infield like all new balls, in an exercise the basemen call “a little pepper.” “OW!”, yells Abner each time he lands in a baseman’s mitt, and even more when tossed with power to the shortstop, only two feet away. Finally, he is rubbed up with dirt, which Abner equates to “brushing your teeth with dry sand.”

A first strike is called. Though property of Yankee Stadium, Abner chants quietly in favor of this, noting to the audience that “When you’re a baseball, you root for both pitchers.” But the peace is not long to last, as Sol is blasted out of the park by Yogi. Abner can’t precisely see what happened, but has the unavoidable feeling that Sol is not long for this ball park – “and neither was I.” Abner emerges into the sunlight, as the umpire tosses him to the catcher. During a meeting at the mound to discuss how to address the next batter, the catcher roughs Abner up within his mitt so much, Abner wonders if he’s been dinged already and will be taken out of the game. No such luck. Instead, he gets tossed around the infield like all new balls, in an exercise the basemen call “a little pepper.” “OW!”, yells Abner each time he lands in a baseman’s mitt, and even more when tossed with power to the shortstop, only two feet away. Finally, he is rubbed up with dirt, which Abner equates to “brushing your teeth with dry sand.”

The first pitch of Abner. A comfortable strike into the catcher’s mitt. “That’s one of ‘em”, he thinks. But the call is the subject of a rhubarb with the umpire, and the manager is ejected from the game. Abner thinks he can use the interruption as opportunity for a short nap – until the basemen start tossing him around again for more “pepper”. Abner feels the bat for the first time on the next pitch, but draws laughs from the crowd as he is hit foul, carroming off the framework of the window of the announcer’s booth. Finally, a third pitch, and one out is declared. Still Anber can find no peace, getting “pepper”-tossed again. As his eyes roll, Abner states. “You can’t win.”

The inning progresses. One more out, and two walks. The pitcher’s spot (before there were designated hitters) coming up. Abner, anticipating a weak batter, keeps repeating to himself, “Pop-up. Pop-up”, thinking an easy out is imminent, and the game will be over. Then, it suddenly dawns on him. “Bottom of the ninth? Two out? WHAT pitcher?” His worst fears are confirmed, as the Yanks call for a pinch hitter – none other than Mickey Mantle! “My cork heart sunk to the inside of my twine.” Abner envisions the most grizzly thoughts of what this guy could do to him. Get a piece of him and twist him permanently out of shape. Hit him foul about 45 times until he loses his marbles for good. Hit him for a line drive into a hot dog griddle. The bleacher bums begin their chant again, including the one who wants to tear the cover off, who changes his shout to “Tear the stitches out of it and send it to Weehawken!” “Oh, how I hate that guy”, mutters Abner. The first pitch is called a ball, and Abner is a bit relieved, noting that even the infielders didn’t throw him around, afraid that somehow, Mantle might steal First. But the catcher has another meeting with the pitcher. He suggests that the bleachers are 450 feet away, so throw it high and outside, and let Mantle hit it. “Let him HIT it?”. questions Abner at first thought – but then begins to think that the odds are that it’ll be a fly ball. Get caught in the outfield, and then he can get a decent night’s rest. “Okay, catcher, I’m with you”, responds Abner to unhearing ears. The pitch is thrown – but Mantle leans into the pitch – “and let me have it.” Soaring like a rocket, and viewing the stadium as if from a flying saucer, Abner leaves the park. Five minutes later, he hits the city pavement and bounces inti a sandlot. One of the kids within makes off with him, but doesn’t head home or to the subway. He runs back to the stadium, to get Abner autographed by the guy who clouted him. “The kid has a soul”, remarks Abner. The Yankees buy the ball from the kid for $50 and a new ball, and Yogi Berra (in the record, it was Casey Stengel) kisses Abner. Then Abner finds out what it’s all about. Mickey has hit him for the world’s longest home run. (This feat is perhaps a Yankee fan’s wishful thinking and flight of fancy, as Mickey did hit one of baseball’s longest homers at 565 feet, but the cartoon version has someone chalking up on a board the whopping number of 987 feet!) And so, Abner is shipped to Cooperstown, taking his place among baseballs hit by the sport’s greatest (a gallery of illustrious names is depicted in both the film and the record). Abner has only one complaint, as he reveals his backside, with some visible red throbbing around the autographed name of Mickey Mantle. “You know, where Mickey signed me, it still hurts.”