A cross-section of television from the early 1960’s is on tap today. There’s a few more illustrious notables of the live-action hosted or “self-hosted” variety of half-hour animation blocks. But there’s also some projects creatively playing with the medium of drawing, or with camera tricks unique to the medium of TV.

Felix the Cat, as reimagined/reintroduced by Paramount’s Joe Oriolo, didn’t often acknowledge that any of his adventure-filled existence wasn’t absolute reality. However, a notable exception occurred in The Mouse and Felix (circa 1961). In those days, all Felix episodes were aired as two-part cliffhangers. In the middle of the story, an art card for Trans-Lux would appear on the screen, leaving Felix in peril or a puzzle, while Jack Mercer (who supplied all voices for the show), would narrate in an ominous tone, “What will happen to Felix in the next exciting chapter of the adventures of Felix the Cat?” Iris out. Of course, no one had the answer until the next air date. But in this installment, we get a surprise. The scene opens in Felix’s living room, with Felix watching TV from an easy chair. We do not see the screen – only the glow of the cathode ray tube – as the voice of Felix is heard from the set, shouting, “Help! Help! I’m trapped!” On comes the usual text of narration for the chapter break (though oddly delivered by Mercer in a different voice register than usual. The series was reputedly known for having Mercer avoid vocal looping in recording between respective voices to cut costs, so it probably would have been a no-no to actually cut-in Mercer’s previously-recorded track of the narration line.) As the ever=present question of Felix’s future fate is posed, Felix turns to the audience with a confident, telling smile and wink, and remarks with a degree of self-pride, “I know what happens!” This unusual piece of introspection may likely have been the brainchild of Mercer himself, who was frequently known for contributing scripts for his own characters, and probably quipped this line at some point during a rehearsal.

Felix the Cat, as reimagined/reintroduced by Paramount’s Joe Oriolo, didn’t often acknowledge that any of his adventure-filled existence wasn’t absolute reality. However, a notable exception occurred in The Mouse and Felix (circa 1961). In those days, all Felix episodes were aired as two-part cliffhangers. In the middle of the story, an art card for Trans-Lux would appear on the screen, leaving Felix in peril or a puzzle, while Jack Mercer (who supplied all voices for the show), would narrate in an ominous tone, “What will happen to Felix in the next exciting chapter of the adventures of Felix the Cat?” Iris out. Of course, no one had the answer until the next air date. But in this installment, we get a surprise. The scene opens in Felix’s living room, with Felix watching TV from an easy chair. We do not see the screen – only the glow of the cathode ray tube – as the voice of Felix is heard from the set, shouting, “Help! Help! I’m trapped!” On comes the usual text of narration for the chapter break (though oddly delivered by Mercer in a different voice register than usual. The series was reputedly known for having Mercer avoid vocal looping in recording between respective voices to cut costs, so it probably would have been a no-no to actually cut-in Mercer’s previously-recorded track of the narration line.) As the ever=present question of Felix’s future fate is posed, Felix turns to the audience with a confident, telling smile and wink, and remarks with a degree of self-pride, “I know what happens!” This unusual piece of introspection may likely have been the brainchild of Mercer himself, who was frequently known for contributing scripts for his own characters, and probably quipped this line at some point during a rehearsal.

The remainder of the episode has little in self-reference, but is among the most entertaining and well-written episodes of the series, again potentially revealing Mercer’s authorship. Objects of food, small and large, begin travelling across Felix’s living room and kitchen. We bever see who is carrying them, though Felux assumes it is a mouse by their destination into a wall. The visual gimmick is that both the entrance to the hole in the wall, and a panel to the refrigerator, can magically at will be enlarged by a simple thin outline appearing on the wall or refrigerator, opening like a hinged panel, then the line erasing itself to return the hole seamlessly to its original dimensions. Kind of wild, but definitely different. Maybe the mouse posesses an unseen magic pencil, Clyde Crashcup patent pending. Anyway, after several failed attempts to thwart the rodent, one of which floods Felix’s entire house, Felix resorts to a vacuum cleaner at the mousehole. The first thing he sucks out is a surprise – a baby bottle, with nipples for seven babies. The next confirms the suspicion – yielding a clothesline full of baby clothes. Felix declares, ‘Gosh, I’m an uncle.” Having respect for a family man – er, mouse – Felix constructs a luxury canopy entrance to the mousehole, complete with red carpet, and surrounded by plenty of foodstuffs. He smiles to us as an iris begins to close on the shot – but the full closing is prevented at the last second, by the hands of – at last – the mouse, who thrusts the iris partway open to finally show himself, and give Felix a wink of approval for his efforts. Felix lets out with his trademark laugh, as the scene fades out. Memories of the many iris-out gags we’ve reviewed in the course of this series.

The remainder of the episode has little in self-reference, but is among the most entertaining and well-written episodes of the series, again potentially revealing Mercer’s authorship. Objects of food, small and large, begin travelling across Felix’s living room and kitchen. We bever see who is carrying them, though Felux assumes it is a mouse by their destination into a wall. The visual gimmick is that both the entrance to the hole in the wall, and a panel to the refrigerator, can magically at will be enlarged by a simple thin outline appearing on the wall or refrigerator, opening like a hinged panel, then the line erasing itself to return the hole seamlessly to its original dimensions. Kind of wild, but definitely different. Maybe the mouse posesses an unseen magic pencil, Clyde Crashcup patent pending. Anyway, after several failed attempts to thwart the rodent, one of which floods Felix’s entire house, Felix resorts to a vacuum cleaner at the mousehole. The first thing he sucks out is a surprise – a baby bottle, with nipples for seven babies. The next confirms the suspicion – yielding a clothesline full of baby clothes. Felix declares, ‘Gosh, I’m an uncle.” Having respect for a family man – er, mouse – Felix constructs a luxury canopy entrance to the mousehole, complete with red carpet, and surrounded by plenty of foodstuffs. He smiles to us as an iris begins to close on the shot – but the full closing is prevented at the last second, by the hands of – at last – the mouse, who thrusts the iris partway open to finally show himself, and give Felix a wink of approval for his efforts. Felix lets out with his trademark laugh, as the scene fades out. Memories of the many iris-out gags we’ve reviewed in the course of this series.

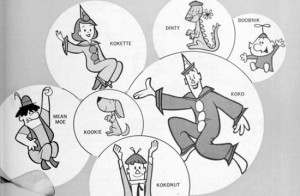

Hal Seeger also chose to revive an old property – producing a whole line of color Out of The Inkwell cartoons with Koko the Clown circa 1961, and even making name reference to Max Fleischer or “Uncle Max, who is briefly seen in quite aged form in a few stock shots filmed for early installments, but is never heard, his voice dubbed by a much more youthful man. There was no sign to be found in these five-minute shorts of Koko’s dog Fitz. Instead, cast was expanded to include a clown-suit girlfriend for Koko named Kokette, a quirky friend who talks like Jerry Colonna with a catch-phrase “and vice versa” named Kokonut, and a recurring “frenemy” to cause mischief named Mean Moe, who talks in mock-Greek dialect. Most episodes were generally typical cartoons of the day in limited animation, frameworked by allegedly being painted on a drawing board. But once in a while, an idea could get creative with the drawing medium. A good example is The Refriger-raider. The alleged hand of Max draws in Koko and Kokette, who comment favorably on a nice background painting Max has created on another board, except for a splattering of ink in the upper corner marring the view, which everyone suspects was caused in a mischievous moment by Mean Moe. Max asserts the spots are no problem, producing an aerosol can of Ink Eradicator. A quick spritz of the miracle fluid, a wipe of a cloth, and the ink spots are gone. Max leaves for the day, instructing Koko and Kokette to do their best to keep Mean Moe out of the refrigerator. But Moe has been hearing and observing all that has happed from under the loose stopper of his own inkwell, and sees possibilities in Max’s aerosol can.

Hal Seeger also chose to revive an old property – producing a whole line of color Out of The Inkwell cartoons with Koko the Clown circa 1961, and even making name reference to Max Fleischer or “Uncle Max, who is briefly seen in quite aged form in a few stock shots filmed for early installments, but is never heard, his voice dubbed by a much more youthful man. There was no sign to be found in these five-minute shorts of Koko’s dog Fitz. Instead, cast was expanded to include a clown-suit girlfriend for Koko named Kokette, a quirky friend who talks like Jerry Colonna with a catch-phrase “and vice versa” named Kokonut, and a recurring “frenemy” to cause mischief named Mean Moe, who talks in mock-Greek dialect. Most episodes were generally typical cartoons of the day in limited animation, frameworked by allegedly being painted on a drawing board. But once in a while, an idea could get creative with the drawing medium. A good example is The Refriger-raider. The alleged hand of Max draws in Koko and Kokette, who comment favorably on a nice background painting Max has created on another board, except for a splattering of ink in the upper corner marring the view, which everyone suspects was caused in a mischievous moment by Mean Moe. Max asserts the spots are no problem, producing an aerosol can of Ink Eradicator. A quick spritz of the miracle fluid, a wipe of a cloth, and the ink spots are gone. Max leaves for the day, instructing Koko and Kokette to do their best to keep Mean Moe out of the refrigerator. But Moe has been hearing and observing all that has happed from under the loose stopper of his own inkwell, and sees possibilities in Max’s aerosol can.

Emerging into view, Moe heads straight for the can, and announces that no one is going to keep his appetite from the refrigerator goodies. He tells Koko and Kokette to “disappear for a while”, and fires a spray of the eradicator at each of them. Koko is reduced to only his head and collar, floating in air with nothing holding him up below. Kokette is reduced to nothing but a pair of pretty eyeballs. But never count Koko out. Koko manages to seixe Max’s paintbrush between his teeth, and quickly squiggles a replacement body for himself on the art paper, misshapen and not unlike the fairy-tale “crooked man”. With a forceful leap, Koko launches his head onto the shoulders of the new body, and connects with it. He looks down at his artistic masterpiece, and realizes he better get himself into shape – so, he blows into his thumb, inflating his body framework until it somehow pops back into straight erect form. Now for Kokette. Who asks that Koko draw her back too. “Make me pretty’, she implores. Koko tries his best, but asides to the audience that he never realized how hard it was ro draw a girl. Kokette’s face comes out all right – but her body bilges as if weighing at least 250 pounds. Koko has a bright suggestion to cure her disapproval, asking her to perform a number doing the vigorous dance, the twist. Kokette shimmies better than anybody’s Sister Kate, and within a few choruses regains her rightful curves. But she is exhausted, and now only wants to rest on the drawing paper. Now Koko is left to face Moe alone, who has already entered Max’s real-life portable refrigerator, and is downing large mouthfuls of strawberry cake. Koko slips up behind him without disturbing him, then suggest that a touch of red sauce in a bottle behind him would go perfectly with that pink cake. The surprised and somewhat-puzzled Moe remains open for dietary suggestion, and says he will try the sauce. Koko pours a good helping down Moe’s throat. Within a moment, Moe’s eyes begin to spiral, and flames shoot out of his mouth. Koko steps back to reveal the label on the bottle. Horse Radish. “WATER!!” screams Moe. Koko zips over to another drawing board, and using Max’s brush, paints a placid lake. Moe runs at full speed toward the drawing, and leaps with full force to dive in. Instead of settling in the water, Moe soars right through the paper, disappearing through a hole in it, and landing headfirst in a booby-trap Koko has laid for him – Moe’s inkwell resting on the desk behind the drawing paper. Koko pits in the stopper, stopping Moe’s antics at least for today. Koko returns to his own inkwell, but spots Kokette asleep in the hard drawing paper where Koko redrew her in. Koko cures the problem by taking Max’s brush again, and drawing a comfortable hammock suspended between two trees under her, then adds a sign below saying “Do Not Disturb”, before himself descending into the inkwell to bed down for the night. Too bad all episodes of the series didn’t show quite this level of creativity. Nevertheless, this neglected, rarely-seen series remains generally on a par with other Paramount-related projects of its day, and, if elements can be located, is sorely deserving of a restoration.

Emerging into view, Moe heads straight for the can, and announces that no one is going to keep his appetite from the refrigerator goodies. He tells Koko and Kokette to “disappear for a while”, and fires a spray of the eradicator at each of them. Koko is reduced to only his head and collar, floating in air with nothing holding him up below. Kokette is reduced to nothing but a pair of pretty eyeballs. But never count Koko out. Koko manages to seixe Max’s paintbrush between his teeth, and quickly squiggles a replacement body for himself on the art paper, misshapen and not unlike the fairy-tale “crooked man”. With a forceful leap, Koko launches his head onto the shoulders of the new body, and connects with it. He looks down at his artistic masterpiece, and realizes he better get himself into shape – so, he blows into his thumb, inflating his body framework until it somehow pops back into straight erect form. Now for Kokette. Who asks that Koko draw her back too. “Make me pretty’, she implores. Koko tries his best, but asides to the audience that he never realized how hard it was ro draw a girl. Kokette’s face comes out all right – but her body bilges as if weighing at least 250 pounds. Koko has a bright suggestion to cure her disapproval, asking her to perform a number doing the vigorous dance, the twist. Kokette shimmies better than anybody’s Sister Kate, and within a few choruses regains her rightful curves. But she is exhausted, and now only wants to rest on the drawing paper. Now Koko is left to face Moe alone, who has already entered Max’s real-life portable refrigerator, and is downing large mouthfuls of strawberry cake. Koko slips up behind him without disturbing him, then suggest that a touch of red sauce in a bottle behind him would go perfectly with that pink cake. The surprised and somewhat-puzzled Moe remains open for dietary suggestion, and says he will try the sauce. Koko pours a good helping down Moe’s throat. Within a moment, Moe’s eyes begin to spiral, and flames shoot out of his mouth. Koko steps back to reveal the label on the bottle. Horse Radish. “WATER!!” screams Moe. Koko zips over to another drawing board, and using Max’s brush, paints a placid lake. Moe runs at full speed toward the drawing, and leaps with full force to dive in. Instead of settling in the water, Moe soars right through the paper, disappearing through a hole in it, and landing headfirst in a booby-trap Koko has laid for him – Moe’s inkwell resting on the desk behind the drawing paper. Koko pits in the stopper, stopping Moe’s antics at least for today. Koko returns to his own inkwell, but spots Kokette asleep in the hard drawing paper where Koko redrew her in. Koko cures the problem by taking Max’s brush again, and drawing a comfortable hammock suspended between two trees under her, then adds a sign below saying “Do Not Disturb”, before himself descending into the inkwell to bed down for the night. Too bad all episodes of the series didn’t show quite this level of creativity. Nevertheless, this neglected, rarely-seen series remains generally on a par with other Paramount-related projects of its day, and, if elements can be located, is sorely deserving of a restoration.

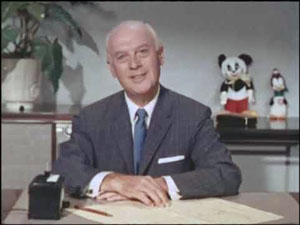

Perhaps no show came closer to mimicking the style of Walt Disney’s presentations of “Disneyland” than The Woody Woodpecker Show, sponsored by Kellogg’s. The similarities were far from accidental. Walter himself had been known even in the golden age of theatrical cartoons to parallel Disney whenever possible. He shortened his own screen billing to ‘Walt Lantz” for a time during the 1940’s. He hired a leading Disney director, Dick Lundy, to helm his studio during its prime period of production for United Artists in the late 1940’s – even distributing through Disney’s old distribution studio during this period. In clever copycat of the defunct “Silly Symphonies” brand, Walter launched the “Swing Symphony” and “Musical Miniature” series. So it was no surprise that when Jack Hannah became available from the ranks of Disney. Lantz would snatch him up, and put him to work producing not only new theatrical cartoons, but TV segments in which Lantz could play on-screen host from a private office or behind the scenes in the studio, with Woody making appearances on the drawing board or upon the office furniture to exchange wise-cracks with “My boss, Walter Lantz”. Lantz made an appealing host with personable charm, though as usual perhaps a notch below Disney. Still, his sequences on the show were memorable, and attempted to take the viewer through most of the finer points in production of a cartoon, with artwork and pencil tests from several recognizable Lantz productions, and on-screen appearances by such studio veterans as Alex Lovy and writer Homer Brightman, among many others. Many of these segments have been compiled and preserved, and a cross-section is presented below.

Perhaps no show came closer to mimicking the style of Walt Disney’s presentations of “Disneyland” than The Woody Woodpecker Show, sponsored by Kellogg’s. The similarities were far from accidental. Walter himself had been known even in the golden age of theatrical cartoons to parallel Disney whenever possible. He shortened his own screen billing to ‘Walt Lantz” for a time during the 1940’s. He hired a leading Disney director, Dick Lundy, to helm his studio during its prime period of production for United Artists in the late 1940’s – even distributing through Disney’s old distribution studio during this period. In clever copycat of the defunct “Silly Symphonies” brand, Walter launched the “Swing Symphony” and “Musical Miniature” series. So it was no surprise that when Jack Hannah became available from the ranks of Disney. Lantz would snatch him up, and put him to work producing not only new theatrical cartoons, but TV segments in which Lantz could play on-screen host from a private office or behind the scenes in the studio, with Woody making appearances on the drawing board or upon the office furniture to exchange wise-cracks with “My boss, Walter Lantz”. Lantz made an appealing host with personable charm, though as usual perhaps a notch below Disney. Still, his sequences on the show were memorable, and attempted to take the viewer through most of the finer points in production of a cartoon, with artwork and pencil tests from several recognizable Lantz productions, and on-screen appearances by such studio veterans as Alex Lovy and writer Homer Brightman, among many others. Many of these segments have been compiled and preserved, and a cross-section is presented below.

Speaking of Jack Hannah, mention is due of one theatrical title (his first Woody for the studio) which I overlooked in past articles. Southern Fried Hospitality (11/26/60) is a tour-de-force for Hannah’s favorite recurring villain for the series – Gabby Gator. Things are tough at Okee-Dokie Swamp. Florida is experiencing a building boom, and new housing is springing up so fast, Gabby literally has to attempt to hold the walls of the buildings back as he fights for “elbow-room”. He is ultimately squashed between the residential encroachments, then left with his “back against the wall” as he is slammed backwards into one of brick. In a stranglehold on his waist, a narrator notes that he must “tighten his belt, or face starvation.” Retreating to a lonely cabin in the thick of the everglades, Gabby moans that he would eat ome dinner, if he had some dinner to eat dinner with. In hopeless effort to pass the time, he thumbs through a cook book, finding a recipe for Fricassee of young woodpecker. Gabby recalls seeing a woodpecker around here, and soon spots where – on the cover of a Hollywood magazine entitled “Modern Screen”, where a portrait of Woody appears in beret hat and sunglasses. The main ingredient has been found. But how to get him down here? Gabby begins typing a formal letter to Woody, care of the studio, inviting Woody to perform as star of a U.S.O. show to “entertain the troops”. The letter adds that they are “hungering” for Woody’s kind of entertainment. Gabby posts the letter, then rushes back to his cabin, rearranging a window curtain in front of the top grill of his pot-bellied stove. “The stage is set”, declares the eager gator.

Speaking of Jack Hannah, mention is due of one theatrical title (his first Woody for the studio) which I overlooked in past articles. Southern Fried Hospitality (11/26/60) is a tour-de-force for Hannah’s favorite recurring villain for the series – Gabby Gator. Things are tough at Okee-Dokie Swamp. Florida is experiencing a building boom, and new housing is springing up so fast, Gabby literally has to attempt to hold the walls of the buildings back as he fights for “elbow-room”. He is ultimately squashed between the residential encroachments, then left with his “back against the wall” as he is slammed backwards into one of brick. In a stranglehold on his waist, a narrator notes that he must “tighten his belt, or face starvation.” Retreating to a lonely cabin in the thick of the everglades, Gabby moans that he would eat ome dinner, if he had some dinner to eat dinner with. In hopeless effort to pass the time, he thumbs through a cook book, finding a recipe for Fricassee of young woodpecker. Gabby recalls seeing a woodpecker around here, and soon spots where – on the cover of a Hollywood magazine entitled “Modern Screen”, where a portrait of Woody appears in beret hat and sunglasses. The main ingredient has been found. But how to get him down here? Gabby begins typing a formal letter to Woody, care of the studio, inviting Woody to perform as star of a U.S.O. show to “entertain the troops”. The letter adds that they are “hungering” for Woody’s kind of entertainment. Gabby posts the letter, then rushes back to his cabin, rearranging a window curtain in front of the top grill of his pot-bellied stove. “The stage is set”, declares the eager gator.

Soon after, our woodpecker appears in the flesh, following road signs left by the gator directing him to the cabin. “So this is Camp Okee-Dokie. Yecch, what a dump”, comments Woody to himself. Gabby appears at the cabin door, giving Woody a military salute, and dressed in an old rebel outfit and wearing a fake white beard. “Where’s all the troops?” asks Woody. “Son, I’m the only one left” bemoans Gabby. But this won’t prevent the “entertaining of an old soldier”. And Gabby places Woody on top of the stove lid and behind the curtain to get ready for his act, himself taking a seat before the stove front and center. As Woody prepares backstage, Gabby stuffs a few logs inside the stove, and lights a match. Then, he calls for act one. Woody emerges as the curtain opens, dressed in top hat and cane, and performing a soft-shoe dance to Swannee River. As he dances, the lid of the stove changes color from cold gray to toasty glowing red. “My act’s hotter than usual”, states the perspiring Woody. Gabby declares the end of act one, allowing him to add more logs to the fire when the curtain closes. As the curtain opens for act two, Woody sarcastically notes, “Mighty short acts in this show.” More dancing, and more perspiring. “Oh, boy, this is a scorcher”, complains the bird. Gabby reads from his cookbook, “To see if done, test with fork.” When Woody turns in his dance step, Gabby jabs him in the rear end with such an instrument, making Woody utter “Yeowch”, as Gabby quickly closes the curtain on the end of act two. Woody suspects something is up, and peeps out from behind the curtain out of turn. He spots Gabby’s cookbook on a shelf, open to the page with the woodpecker recipe. He also spots Gabby gathering up more logs. The resourceful bird zips behind Gabby unnoticed, and places Gabby’s own tail upon the lumber pile. “Well what do you know? Green wood”, remarks Gabby, as both logs and his tail are cast into the stove. “Something smells scrumptious. Almost…like…alligator?” Gabby flies into the air like a rocket, smashing a hole through the roof, briefly lands in a swamp boat for a short action scene, then smashes back through the roof in a daze, landing upon the stove top. Woody finds a can of fuel marked “Hot Stuff”, and pours it over the stove logs. The whole stove flares up, and Gabby is forced to perform a vigorous dance twice as fiery as Woody’s ever was. “Hot, Daddy-O!”. applauds Woody, now seated in Gabby’s chair and wearing his rebel hat. His trademark laugh, and Woody finally declares. “Show’s over”, pulling the curtain in front of Gabby for the final iris out.

Soon after, our woodpecker appears in the flesh, following road signs left by the gator directing him to the cabin. “So this is Camp Okee-Dokie. Yecch, what a dump”, comments Woody to himself. Gabby appears at the cabin door, giving Woody a military salute, and dressed in an old rebel outfit and wearing a fake white beard. “Where’s all the troops?” asks Woody. “Son, I’m the only one left” bemoans Gabby. But this won’t prevent the “entertaining of an old soldier”. And Gabby places Woody on top of the stove lid and behind the curtain to get ready for his act, himself taking a seat before the stove front and center. As Woody prepares backstage, Gabby stuffs a few logs inside the stove, and lights a match. Then, he calls for act one. Woody emerges as the curtain opens, dressed in top hat and cane, and performing a soft-shoe dance to Swannee River. As he dances, the lid of the stove changes color from cold gray to toasty glowing red. “My act’s hotter than usual”, states the perspiring Woody. Gabby declares the end of act one, allowing him to add more logs to the fire when the curtain closes. As the curtain opens for act two, Woody sarcastically notes, “Mighty short acts in this show.” More dancing, and more perspiring. “Oh, boy, this is a scorcher”, complains the bird. Gabby reads from his cookbook, “To see if done, test with fork.” When Woody turns in his dance step, Gabby jabs him in the rear end with such an instrument, making Woody utter “Yeowch”, as Gabby quickly closes the curtain on the end of act two. Woody suspects something is up, and peeps out from behind the curtain out of turn. He spots Gabby’s cookbook on a shelf, open to the page with the woodpecker recipe. He also spots Gabby gathering up more logs. The resourceful bird zips behind Gabby unnoticed, and places Gabby’s own tail upon the lumber pile. “Well what do you know? Green wood”, remarks Gabby, as both logs and his tail are cast into the stove. “Something smells scrumptious. Almost…like…alligator?” Gabby flies into the air like a rocket, smashing a hole through the roof, briefly lands in a swamp boat for a short action scene, then smashes back through the roof in a daze, landing upon the stove top. Woody finds a can of fuel marked “Hot Stuff”, and pours it over the stove logs. The whole stove flares up, and Gabby is forced to perform a vigorous dance twice as fiery as Woody’s ever was. “Hot, Daddy-O!”. applauds Woody, now seated in Gabby’s chair and wearing his rebel hat. His trademark laugh, and Woody finally declares. “Show’s over”, pulling the curtain in front of Gabby for the final iris out.

A superb, strong personality venture for Hannah’s debut with the studio. I personally have this cartoon as one of my earliest theatrical memories, having seen it a few years following its original release date on a big screen at the Twin Drive-In in Malden, Massachusetts. Some one must have liked the cartoon, as we had driven in too late to see it at the beginning of the program, but for unknown reasons, the projectionist chose to show it again, at the end of the program, after the second feature! It made a lasting impression upon me at the tender age of about six years old, and to this day. I can still see in my mind’s eye the images of both Woody and Gabby dancing on the big screen upon that impressive color-changing pot-bellied stove. It took me about twenty-five years between screenings to see the cartoon a second time – and yet my recollection of the staging and color were absolutely matching the reality when I viewed the film once again. Just shows you the power a well-produced cartoon can have on shaping your memories, and your overall impressions of the industry.

A superb, strong personality venture for Hannah’s debut with the studio. I personally have this cartoon as one of my earliest theatrical memories, having seen it a few years following its original release date on a big screen at the Twin Drive-In in Malden, Massachusetts. Some one must have liked the cartoon, as we had driven in too late to see it at the beginning of the program, but for unknown reasons, the projectionist chose to show it again, at the end of the program, after the second feature! It made a lasting impression upon me at the tender age of about six years old, and to this day. I can still see in my mind’s eye the images of both Woody and Gabby dancing on the big screen upon that impressive color-changing pot-bellied stove. It took me about twenty-five years between screenings to see the cartoon a second time – and yet my recollection of the staging and color were absolutely matching the reality when I viewed the film once again. Just shows you the power a well-produced cartoon can have on shaping your memories, and your overall impressions of the industry.

• You can watch this cartoon on DailyMotion, if you arch your head… CLICK HERE.

Jack Kinney’s Popeye episode, Battery Up, produced for King Features circa 1960, includes an unusual piece of self-reference, during a baseball battle between Popeye (who seems to be playing solo in the manner of Bugs Bunny), and an entire team of Blutos (or Brutuses if you prefer), known as the Boilermaker Boys. The episode is decently written, directed and timed, without the cheats and quality errors which became so prevalent in later Kinney episodes. Popeye endures a wide variety of line-drives and powerful clouts of the horsehide, while he attempts to serve up his own brand of spiraling pitches. Popeye’s slow-ball is one for the books – perhaps the slowest and longest in history, allowing the batter to fall sound asleep while resting upon the end of the bat. The ball still hits the bat, knocking the prop out from under the batter and sending him sprawling, while the ball somehow has the energy to result in a pop fly all the way to the fence, where Popeye stands confidently to catch the pop-up without missing a beat in flirting with Olive in the grandstand. (This film was released by Americom Home Movies in 8mm, with a special record soundtrack slowed for projection at the hone-projector speed of 18 frames per second. One can only wonder how the slow-ball scene must have played out at such a slowed, deliberate tempo.) As Popeye serves up a faster pitch, we get a visual surprise. Bluto’s sock sends the ball flying directly at the camera, the visual image shattering with the cracking of glass, and the screen going entirely blank for a few moments. Our view pulls back from the blackness, revealing a TV screen in a living room, with its picture tube shattered, a gaping hole visible therein. Popeye somehow pops up within the hole, and slides in behind him a new pane of tube glass to mend the damage. “Sorry, folks. Pardon the interruptkions. Due to mechanical difficulties…” He never gets to finish, as he called back to the field by umpire Wimpy’s call of “Play ball!” Ultimately, a power-sock by another batter carries Popeye over the fence with the ball, through the window of an odd shop combining an unlikely pair of lines of merchandise – Sporting Goods and Spinach Store. Need we speak further as to the ultimate outcome of the game?

Jack Kinney’s Popeye episode, Battery Up, produced for King Features circa 1960, includes an unusual piece of self-reference, during a baseball battle between Popeye (who seems to be playing solo in the manner of Bugs Bunny), and an entire team of Blutos (or Brutuses if you prefer), known as the Boilermaker Boys. The episode is decently written, directed and timed, without the cheats and quality errors which became so prevalent in later Kinney episodes. Popeye endures a wide variety of line-drives and powerful clouts of the horsehide, while he attempts to serve up his own brand of spiraling pitches. Popeye’s slow-ball is one for the books – perhaps the slowest and longest in history, allowing the batter to fall sound asleep while resting upon the end of the bat. The ball still hits the bat, knocking the prop out from under the batter and sending him sprawling, while the ball somehow has the energy to result in a pop fly all the way to the fence, where Popeye stands confidently to catch the pop-up without missing a beat in flirting with Olive in the grandstand. (This film was released by Americom Home Movies in 8mm, with a special record soundtrack slowed for projection at the hone-projector speed of 18 frames per second. One can only wonder how the slow-ball scene must have played out at such a slowed, deliberate tempo.) As Popeye serves up a faster pitch, we get a visual surprise. Bluto’s sock sends the ball flying directly at the camera, the visual image shattering with the cracking of glass, and the screen going entirely blank for a few moments. Our view pulls back from the blackness, revealing a TV screen in a living room, with its picture tube shattered, a gaping hole visible therein. Popeye somehow pops up within the hole, and slides in behind him a new pane of tube glass to mend the damage. “Sorry, folks. Pardon the interruptkions. Due to mechanical difficulties…” He never gets to finish, as he called back to the field by umpire Wimpy’s call of “Play ball!” Ultimately, a power-sock by another batter carries Popeye over the fence with the ball, through the window of an odd shop combining an unlikely pair of lines of merchandise – Sporting Goods and Spinach Store. Need we speak further as to the ultimate outcome of the game?

The Bugs Bunny Show (1960) was among the class acts of the self-hosted cartoon

The Bugs Bunny Show (1960) was among the class acts of the self-hosted cartoon

show. Following Disney’s lead, when Warner introduced most of its post-1948 cartoons to TV, it spared little expense in producing classy bridging sequences and main titles, using its top-flight directors for the task. One can in retrospect, however, notice numerous instances where old animation from classic cartoons was reworked for various individual shots of the bridging material. The end result was quite seamless, and in later installments (in which I believe the practice of flashing a title card to begin each episode was abandoned) could lead a young viewer like myself to believe that some episodes were entirely new productions. (I recall seeing in rerun as a youth an episode featuring what I did not know was “Weasel While You Work”, and noting the John Seely music cues which I recognized from other television cartoons of the day – so I automatically presumed that the whole cartoon had been made for TV.) Perhaps most memorable about the whole affair was the series’ energetic theme song, patterned much after “Show Biz Bugs”, with Bugs and Daffy as vaudeville hoofers in straw hats and canes, dancing the memorable “This Is It”. That music, be it the vocal version at the opening or the original extended instrumental at the closing, could brighten a whole day.

As noted by bloggers on this site, some episodes of the show featured spoofs on the animation industry, including one where Daffy appears as an inbetweener, drawing a cel of Bugs which instead looks like himself. Another is reputed to have given Foghorn Leghorn the “Duck Amuck” treatment, though I have never seen it myself. Surviving copies of the show are sadly few and far between on video and internet sources. However, a reconstruction of the complete Episode 5 (11/8/60) is posted on Facebook – CLICK HERE to see it.

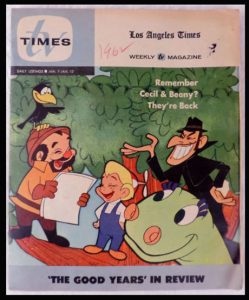

Cecil’s Comical Strip (Bob Clampett, 5/12/62), an episode of Matty’s Funday Funnies with Beany and Cecil, is a pun-filled sendup of the industry of newspaper cartoons, in which Cecil aspires to make his fortune, laboring over a drawing board with spare pencils tucked behind his ear. (Ear? Where is that on a sea serpent?) He takes a large mouthful of completed strips to a row of reefs in the middle of the ocean, which serve as high-rise structures for all the major syndicates. (A building design lampooning King Features syndicate is prominent at the forefront.) Unfortunately, Cecil is forced to start at the bottom, with the lowly Oct-u-puss and Boots Syndicate, where the latest applicant exits the door wearing a boot-print on his rear, stamped with the embedded word, “Reject.” Mr. Octopus is a hard-sell, and turns down proposed strip after strip of Cecil’s. Even when he laughs at one, he quotes an old song title, claiming to be “Laughing on the outside, crying on the inside.” Cecil approaches him closely, pressing his head to him, and asks, “O sir, may I listen?” The puns run rampant, with far too many parodies of the titles of current and past vintage strips to list here, but include spoofs of such favorites as “Little Orphan Annie”, “Mary Worth”, “Terry and the Pirates”, “The Katzenjammer Kids”. “Flash Gordon”, and “Bringing Up Father”. Though Cecil seems to have a comic for every occasion, nothing satisfies Mr. Octopus. Cecil picks up his drawings and prepares to depart, but inadvertently leaves behind one sheet of paper. Mr. Octopus asks what this one is, and Cecil replies that it is only his doodles. “Doodles!”, shouts Mr. Octopus, loving the title, and immediately offers to print it in his publication. Cecil asks how much he’ll be paid for his work. “Pay you? You pay me! After all, that’s the wages of sin – dicates.” Poor Cecil can only look to the camera, and end with the closing line, “You know, being a comical stripper is no laughing matter.”

Cecil’s Comical Strip (Bob Clampett, 5/12/62), an episode of Matty’s Funday Funnies with Beany and Cecil, is a pun-filled sendup of the industry of newspaper cartoons, in which Cecil aspires to make his fortune, laboring over a drawing board with spare pencils tucked behind his ear. (Ear? Where is that on a sea serpent?) He takes a large mouthful of completed strips to a row of reefs in the middle of the ocean, which serve as high-rise structures for all the major syndicates. (A building design lampooning King Features syndicate is prominent at the forefront.) Unfortunately, Cecil is forced to start at the bottom, with the lowly Oct-u-puss and Boots Syndicate, where the latest applicant exits the door wearing a boot-print on his rear, stamped with the embedded word, “Reject.” Mr. Octopus is a hard-sell, and turns down proposed strip after strip of Cecil’s. Even when he laughs at one, he quotes an old song title, claiming to be “Laughing on the outside, crying on the inside.” Cecil approaches him closely, pressing his head to him, and asks, “O sir, may I listen?” The puns run rampant, with far too many parodies of the titles of current and past vintage strips to list here, but include spoofs of such favorites as “Little Orphan Annie”, “Mary Worth”, “Terry and the Pirates”, “The Katzenjammer Kids”. “Flash Gordon”, and “Bringing Up Father”. Though Cecil seems to have a comic for every occasion, nothing satisfies Mr. Octopus. Cecil picks up his drawings and prepares to depart, but inadvertently leaves behind one sheet of paper. Mr. Octopus asks what this one is, and Cecil replies that it is only his doodles. “Doodles!”, shouts Mr. Octopus, loving the title, and immediately offers to print it in his publication. Cecil asks how much he’ll be paid for his work. “Pay you? You pay me! After all, that’s the wages of sin – dicates.” Poor Cecil can only look to the camera, and end with the closing line, “You know, being a comical stripper is no laughing matter.”

NEXT: Later ‘60’s and on.