Here’s a short trail just for fun. Not really a true trail at all, as the topics and subject matter of the films to be discussed here are diverse, as opposed to centered on a particular type of character, subject, or genre. Instead, it is more a little primer on how not to present an animated work, and the various things that can go wrong in trying to capture the illusion of life when you don’t carefully check and plan. Animation is an exacting field, and was certainly subject to a learning curve as time progressed. One would hardly expect the same levels of artwork and quality control from the early animation pioneers of the Bray Studio or others of their time, that would later become commonplace in the heyday of the studios of Disney, Warner, and MGM, Thus, we can be to a degree forgiving at spotting obvious goof-ups in movement, tracing, or what-have-you in the like of early episodes of Aesop’s Fables, Colonel Heeza Liar, Dinky Doodles, etc.

Yet, it’s sometimes fascinating to discover how even the big boys (and girls) of the major Hollywood animation powerhouses of the 30’s, 40’s, and 50’s could falter and stumble, letting through something that, in a day and age when perfection was considered the norm, somehow eluded quality control. Some of these problems disappear in a blink, and have to be carefully watched for (the likely reason why they slipped through in the first place, producers desiring to save money on reshoots and hope that audiences would indeed blink or look the other way to miss them). Others, however, surprisingly stand out like a sore thumb, making one wonder how anyone could possibly not notice, and why the producers of the films could think they could get away with it without tarnishing the reputation of their product. Sometimes, these faux pas can inject a film with an unexpected extra laugh, and a recollection of their presence that makes the viewer want to specially wait for their appearance on every successive viewing. Other times, they can simply leave one scratching one’s head, wondering, “What in te world were they thinking, letting this go?”

Yet, it’s sometimes fascinating to discover how even the big boys (and girls) of the major Hollywood animation powerhouses of the 30’s, 40’s, and 50’s could falter and stumble, letting through something that, in a day and age when perfection was considered the norm, somehow eluded quality control. Some of these problems disappear in a blink, and have to be carefully watched for (the likely reason why they slipped through in the first place, producers desiring to save money on reshoots and hope that audiences would indeed blink or look the other way to miss them). Others, however, surprisingly stand out like a sore thumb, making one wonder how anyone could possibly not notice, and why the producers of the films could think they could get away with it without tarnishing the reputation of their product. Sometimes, these faux pas can inject a film with an unexpected extra laugh, and a recollection of their presence that makes the viewer want to specially wait for their appearance on every successive viewing. Other times, they can simply leave one scratching one’s head, wondering, “What in te world were they thinking, letting this go?”

I’ll try to group discussion of the various types of blunders by category, posting various examples of similar mishaps from various studios. Some of the rarer types of errors, however, seem to be unique to one particular film or one studio, and so may thus be presented as a stand-alone testament to a day gone wrong.

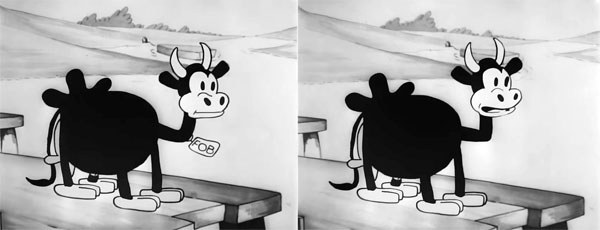

Perhaps a good place to start is what I’ll call the “Disappearing Act”. This subcategory will not include the general garden-variety of mis-tracings where some line or another fails to get transferred from pencil drawing to finished cel through minor carelessness in the ink and paint department. Such errors are far too common to categorize. Many, for example can be seen on a regular basis in lower-budgeted cartoons of the 1930’s, such as Bob Clampett’s Looney Tunes, where inconsistent lines between drawings of Porky Pig and his pals often seemed the order of the day, showing up in almost every episode. This category instead includes the more egregious instances, where entire objects, props, and sometimes characters themselves, briefly disappear from the screen. Devotees of classic animation will likely remember one such instance in perhaps the most famous black and white sound short ever made – Disney’s Steamboat Willie (Mickey Mouse, 7/29/28), where, at approximately 2:10, the cow waiting on the docks lets out with a moo, and on the inhale momentarily has the large neck tag reading “F.O.B.” entirely disappear from the shot, then reappear again.

There’s no way to clearly tell whether this error originated in the paper animation or in the ink and paint retracing, but it’s likely that it was not a mere instance of forgetting to place a finished cel on the camera mount, as the entire character, neck label and all, was probably copied onto a single layer of cel all at once, meaning that the error happened before the finished drawings ever reached the camera room. We again tend to forgive even Disney for such an error in this early formative year, though he had already demonstrated more exacting error-checking in many of his quite sophisticated Oswald shorts for Universal, as he was obviously under pressure to successfully turn out a new product, and having enough trouble worrying about making best use of the new medium of sound, to be bothered with an error that only appeared for a handful of frames. However, it was not the only such error to escape the studio. Witness The Whoopee Party (Mickey Mouse, 9/17/32), produced at a time when Disney was already riding high with success, starting a new lucrative contract with United Artists, and more-or-less at the top of the industry. A time when he should have been able to afford all the quality control he desired. Then how do you account for an entire band member disappearing from the makeshift orchestra at Mickey’s party? Check out the film at approximately 5:44, and watch for the goat violinist at the far left of the screen, who seems to wait about 8 to 12 frames into the shot to suddenly appear from nowhere. This looks like a cameraman’s error, given the complexity of the shot, in failing to place one layer of cels upon the screen when the scene starts out.

There are also a few painting errors in the complex cycles of dancers in the first and third shots of the film. Admittedly, the animation on this one was super-complex, and the smoothness of execution and sheer energy exhibited from a large cast of characters make this film a certified classic. It’s just a surprise that, with everything else in the film going right, Disney couldn’t have gone that one-inch of an extra mile to correct one scene and make the film letter-perfect.

For other, smaller studios, similar problems were perhaps more to be expected in an audience’s eyes, and less likely to be corrected – but certainly no less glaring. Scrappy’s first appearance for Columbia, Yelp Wanted (7/16/31), was marred by an opening shot that few eyes were likely to miss – a scene at the breakfast table, where some animator (Dick Heumor himself, perhaps?) couldn’t seem to decide what props should be present and where they should be arrayed. Scrappy begins his meal with no hat present in the shot, and a glass of juice in close proximity to his bowl (so close, in fact, that it is obvious the object has been painted-in at the wrong location or upon the wrong layer of cels, as it is erroneously eclipsed in part behind Scrappy’s right hand, despite such hand resting upon the near edge of the table, leaving no clear room on the table surface where they glass would cleanly fit). About two seconds elapse. Then with no explanation, the glass leaps to the far left of the screen (not through motion, but by an abrupt shift of the object in a single change of cel), and at the same time, Scrappy’s cloth hat appears from nowhere, now draped over one wooden knob of the back of Scrappy’s chair! The cel of the juice glass is not even the same cel first seen, as there is a change in the location of a reflection line upon the glass surface – meaning that the correction in position was not a matter of merely re-alligning location pegs, but sent to the cameraman that way from ink and paint. How did this insane situation happen? Maybe the missing hat could have been a camera error in not first placing a cel at the beginning of the shot – but the fact that both objects move to proper positions in the same frame more likely indicates they were both painted that way to begin with. We may never know just went wrong here, but, despite the film that follows it being a reasonably well-animated and otherwise high-quality film debut, this jarring first scene could only have signaled to audiences that we were watching the product of a studio who, compared to its competitors, was producing cartoons on the cheap.

Speaking of cheap, then there was Van Beuren. Certainly, no one familiar with the studio’s work would have expected to find any masterpieces here. Yet sometimes, the animators could even undercut their own low threshold for production value. A prime example is The Farmerette (6/28/32). Actually, this cartoon ranks in general on the higher side of the studio’s quality as to fluidity of some animation. But it cost-cuts to afford the better scenes, by recycling an entire song sequence, “Down on the Farm”, from Farm Foolery (1930). What becomes weird is that the retraced or reused drawings from the earlier film, which were properly presented in the original, suddenly present a jarring and eye-popping foul-up that was never previously seen. A quartet of dogs appears at approximately 4:44, breaking into a variant on the childish gibberish, “Eep, ipe, wanna piece of pie” (also used later in a Fats Waller song), their torsos performing a swaying dance cycle animated on separate cels from the heads. It may be possible each dog’s body is on a separate cel layer than the bodies of the others – because, for what seems to be over a full second, one dog’s body completely disappears! – yet reappears again, performing the exact cycle of swaying movements as he should have performed in the missing second of film and as he had in the 1930 shot. So the cels for the dancing were in fact provided to the cameraman – yet somehow evaded appearing before the lens for the full second. Someone really fell asleep at the wheel – either in writing instructions for the cel placement, or more likely at the camera switch. How could the operator possibly fail to notice a song being sung by a floating head? Worse yet, how could it be approved for release from the executives watching the final rushes?

Did Bluto ever appear bottomless? Well, at least once. Thus came about in Famous Studios’ Robin Hoodwinked (11/12/48). Famous was generally a well-organized studio, whose artwork (with the exception of a few productions by Jim Tyer) exhibited clean lineage and fairly meticulous painting, rarely showing any signs of error (though a possible exception would be a wrestling sequence involving a hippo which first appeared in a Screen Song and was also spliced into “Sportickles”, where a new color paint chosen for the hippo did not spead evenly, and came out looking blotchy from cel to cel). In fact, the error in the case of the Bluto appearance could in no manner be attributed to either the animators or ink and paint, who each did their job in the customary manner. Instead, the fault seems to rest with the layout department. It’s hard to tell what sort of large object was supposed to appear in the foreground in the setting of Olive’s tavern. (A table? An ale barrel?) But it is clear from the way a scene was set up that something in the form of a stationary prop overlay was supposed to appear on a separate cel, to be placed over the top of the animation of Bluto, to partially eclipse him. Instead, the elusive cel of the object seems to never have been delivered to the cameraman – or else was carelessly overlooked by him in setting up the shot. The result was that the cels of Bluto were photographed fully revealed in the foreground, just as they had been completed by ink and paint. This might have been all right if the animators had not been tipped off in advance than an object was supposed to be in the foreground. Knowing this, the animators only drew Bluto down to the hams of his legs, never completing the drawings to extend the lineage of his limbs down to the floor. Ink and paint, having no clear guidelines as to where character ended and prop was to begin, randomly painted each cel only so far as they believed the leg outlines would extend, each cel different from the next and previous, with the brush strokes ending at different positions and elevations – all expected to be covered up in the final shot. With no covering provided to the camera, we see the hilarious behind-the-scenes result at approximately 3:30 (1:16 in the excerpt below) of Bluto defying gravity, transported in air upon legless limbs, with color edge bobbing randomly up and down with every change of position! One of the most outrageous errors to hit the big screen, looking like someone accidentally released a pencil test painted in. We can surmise just how the error happened – but can anyone explain why it wasn’t caught for a reshoot?

Did Bluto ever appear bottomless? Well, at least once. Thus came about in Famous Studios’ Robin Hoodwinked (11/12/48). Famous was generally a well-organized studio, whose artwork (with the exception of a few productions by Jim Tyer) exhibited clean lineage and fairly meticulous painting, rarely showing any signs of error (though a possible exception would be a wrestling sequence involving a hippo which first appeared in a Screen Song and was also spliced into “Sportickles”, where a new color paint chosen for the hippo did not spead evenly, and came out looking blotchy from cel to cel). In fact, the error in the case of the Bluto appearance could in no manner be attributed to either the animators or ink and paint, who each did their job in the customary manner. Instead, the fault seems to rest with the layout department. It’s hard to tell what sort of large object was supposed to appear in the foreground in the setting of Olive’s tavern. (A table? An ale barrel?) But it is clear from the way a scene was set up that something in the form of a stationary prop overlay was supposed to appear on a separate cel, to be placed over the top of the animation of Bluto, to partially eclipse him. Instead, the elusive cel of the object seems to never have been delivered to the cameraman – or else was carelessly overlooked by him in setting up the shot. The result was that the cels of Bluto were photographed fully revealed in the foreground, just as they had been completed by ink and paint. This might have been all right if the animators had not been tipped off in advance than an object was supposed to be in the foreground. Knowing this, the animators only drew Bluto down to the hams of his legs, never completing the drawings to extend the lineage of his limbs down to the floor. Ink and paint, having no clear guidelines as to where character ended and prop was to begin, randomly painted each cel only so far as they believed the leg outlines would extend, each cel different from the next and previous, with the brush strokes ending at different positions and elevations – all expected to be covered up in the final shot. With no covering provided to the camera, we see the hilarious behind-the-scenes result at approximately 3:30 (1:16 in the excerpt below) of Bluto defying gravity, transported in air upon legless limbs, with color edge bobbing randomly up and down with every change of position! One of the most outrageous errors to hit the big screen, looking like someone accidentally released a pencil test painted in. We can surmise just how the error happened – but can anyone explain why it wasn’t caught for a reshoot?

Speaking of defying gravity, though to my knowledge no surviving footage has turned up from which to verify the tale, legend has it that an unidentified episode of Mutt and Jeff from the silent days was responsible for being the first film to have a character break Newton’s law – all quite by accident. The story is that Jeff was supposed to cavort along the top of, or lean against, a fence railing – and, similar to the Bluto error, someone forgot to provide the cel or background that was to depict the fence. So Jeff’s weight was supported on the screen by absolutely nothing. To the studio’s surprise, the scene delivered an unexpected responsive laugh – and the producers noticed. The next time any of their characters would walk on air, the act was purely intentional.

Perhaps my favorite disappearing trick of all was one which might have slipped by if the cameraman had just stuck with his error through the duration of the sequence, but instead, the error was caught only after the LONGEST time, with disastrous results. The scene takes place in the Walter Lantz Woody Woodpecker short, Smoked Hams (4/28/47). At approximately 1:13, Woody Woodpecker, night sleeper, is awakening just at the commencement of bedtime for Wally Walrus, day sleeper. A cuckoo-clock alarm above Woody’s bed features a Germanic figurine which empties a small bucket of water into the snoring Woody’s throat. Woody awakens gagging and coughing, emitting one very loud cough to spit out the last traces of water. As he performs such cough, the oversize pillow upon which he has been resting his head suddenly disappears. The synchronization of its disappearance with Woody’s cough at first makes the viewer explain what he is seeing by thinking, “Did Woody cough hard enough to cause the pillow to disintegrate?” A strange notion, but the eyes might have accepted it – if the pillow had just remained out of view for the rest of the scene. Instead, after a good two seconds of absence, the pillow returns! – remaining fully visible for at least another five seconds, giving the audience full opportunity to register its magical comeback. Worse yet, the pillow hasn’t moved from its lasr-seen position, and did not seem to be involved in any of the action of Woody following his cough – so it does not appear that there were any cels omitted from delivery to the camera room. Could someone have overlooked providing instructions to continue to leave the pillow cel on the screen during Woody’s action? If so, why would this get picked up again later in the instructions for the end of the shot, when there is no clear indication of any action by the pillow to even require a change of cel? It seems considerably more likely that, even if the instructions forgot to mention to use the pillow cel upon Woody’s cough, they likely never brought up the subject again for the remainder of the shot.

Perhaps my favorite disappearing trick of all was one which might have slipped by if the cameraman had just stuck with his error through the duration of the sequence, but instead, the error was caught only after the LONGEST time, with disastrous results. The scene takes place in the Walter Lantz Woody Woodpecker short, Smoked Hams (4/28/47). At approximately 1:13, Woody Woodpecker, night sleeper, is awakening just at the commencement of bedtime for Wally Walrus, day sleeper. A cuckoo-clock alarm above Woody’s bed features a Germanic figurine which empties a small bucket of water into the snoring Woody’s throat. Woody awakens gagging and coughing, emitting one very loud cough to spit out the last traces of water. As he performs such cough, the oversize pillow upon which he has been resting his head suddenly disappears. The synchronization of its disappearance with Woody’s cough at first makes the viewer explain what he is seeing by thinking, “Did Woody cough hard enough to cause the pillow to disintegrate?” A strange notion, but the eyes might have accepted it – if the pillow had just remained out of view for the rest of the scene. Instead, after a good two seconds of absence, the pillow returns! – remaining fully visible for at least another five seconds, giving the audience full opportunity to register its magical comeback. Worse yet, the pillow hasn’t moved from its lasr-seen position, and did not seem to be involved in any of the action of Woody following his cough – so it does not appear that there were any cels omitted from delivery to the camera room. Could someone have overlooked providing instructions to continue to leave the pillow cel on the screen during Woody’s action? If so, why would this get picked up again later in the instructions for the end of the shot, when there is no clear indication of any action by the pillow to even require a change of cel? It seems considerably more likely that, even if the instructions forgot to mention to use the pillow cel upon Woody’s cough, they likely never brought up the subject again for the remainder of the shot.

Some considerable degree of blame must thus be placed upom the shoulders of the cameraman, who either began the blunder himself by ignoring instructions, or blindly followed directions to omit the pillow, only to have the realization hit him partway through his work that something was amiss. What to do, what to do? Rather than stick to his guns and complete the shot with the immobile prop gone, in hopes (which might have been realized) that no one but the very observant would notice, the chump cameraman decides to do the noble thing and “rescue” the shot by putting the pillow back – after a lapse so long, it would be impossible for anyone in the audience not to notice that the pillow had been mistakenly gone! By not following orders, either in misreading instructions to begin with or using his own discretion too late to override erroneous instructions, the cameraman thus created a glaring error for the ages, unique to this film. And again, what was going on in the review of the completed footage? This was Dick Lundy, an ex-Disney man used to dealing with painstaking neatness, directing this cartoon. How could he possibly miss this? Was the production running behind schedule for release, with absolutely no time for a reshoot and re-edit? If Lundy was told this, were there no heated words exchanged in the studio corridors about his being deprived of reasonable opportunity to avoid critical embarrassment among his ex-associates at Disney and other peers from the industry? As recently quoted in the Disney short, Once Upon a Studio, “If these walls could talk….”

Visuals weren’t the only instance where a disappearing act could take place. The same could be true of the audio. Principal among this type of problem was the Van Beuren studio. While music scoring was generally no sweat, such tracks often probably being laid down in one continuous take with the visual aid of the “Rufle baton”, dialogue and sound effects were often another matter. These would be recorded on separate tracks from separate mikes, and had to be spliced in and mixed with the background score. Van Beuren’s sound editing was often rough, with mild audio pops heard before or after lines or effects, and microphone ambience changes for certain lines at times feel jarring against the clean sound of the orchestra. Perhaps the most disturbing ambience change occurred in Cubby Bear’s Galloping Fanny (12/1/33), in which the horse providing the cartoon’s title is given a Mae West-style voice, likely provided by someone not a regular part of the studio’s voice crew. The miking of her few lines of dialog is so bad, it sounds like they caught her in the ladies’ rest room!

Though these problems were inconsistent, they continued right up through the last color films of the studio (Felix the Cat’s Bold King Cole containing several). What became embarrassing was that, as animation and scripts became more sophisticated, the sound crew sometimes seemed unable to keep up with developments, and either forgot to splice in certain planned lines of dialog or audio effects, or didn’t closely follow the shooting scripts and neglected to record the sound altogether. This resulted in multiple instances of characters acting on the screen – but nothing coming out. One of the first notables of this kind was Tom and Jerry’s Magic Mummy (2/7/33). In the final shot, Jerry returns to police headquarters, carrying a sarcophagus. He shouts to the chief to get his attention – that is, his lips move as if he were shouting. All we hear on the track is an opening audio pop, and a closing audio pop, although Jerry’s lips clearly mouth the words, “The Mummy!” The scene is slightly saved, only because the next dialog has the rest of the police force repeating over and over, “The mummy! The mummy!”, giving us a clear idea of what Jerry must have said. This is probably why the studio figured it could get away with leaving the sound error alone, as it made no great difference to understanding the plot, even though it was audibly noticeable. Of course, when the mummy case is opened, all the police find within it is a staggering Tom.

More such problems from Van Beuren included The Rag Dog (7/19/35). Here, while perhaps not as noticeable, two dogs engage in considerable barking, as three mischievous kittens try to spook them by dressing up in a rag-doll dog and making it seem to come to life for an attack. If one watches closely, however, you will find that the barks seem to be dropped in rather arbitrarily, and, though the dogs continue to bark in a sequence upon and in front of a china cabinet, many of their yapping movements utter no sounds, while their jaws open and close as vigorously as their loudest barks in other scenes of the picture. Clearly, something was left out.

A further, and much more blatant, failure to cut-in dialog appears in Felix the Cat’s Neptune Nonsense (3/20/36), As Felix is arrested to stand trial, we are introduced to the presiding judge, King Neptune, via a shot where he flirtatiously provides musical accompaniment to a small shimmy-dancing topless mermaid, as he plucks out the strains of “Aloha Oe” on the tines of his trident. After he receives a few kisses from the aquatic maiden, the police usher Felix in, causing Neptune to give a signal to the mermaid to scoot off until later. Neptune then lifts his gavel, pounding it a few times upon the bench, and twice mouths the words of the familar call, “Order in the court! Order in the court!” But not a sound leaves his lips – although the audio editor at least remembers to cut in the sound effect of the gavel. Not fatal to plot continuiyy, but still a highly-noticeable snafu – especially when the missing dialog lines are so predictable, and naturally expected to be heard by the audience.

The poster for the 1949 re-release

Returning to the subject of bad audio editing, we’ll close this week’s installment with what must qualify as possibly the worst audio work to ever appear in a major studio cartoon – Flip the Frog’s Laughing Gas (Ub Iwerks/MGM, 5/1/31). Isolated instances of the type of problems associated with this film briefly appear in other productions by Iwerks of the time, such as in the introductory scenes of “Ragtime Romeo” – but “Gas” is a real gas for its outright atrocity – audio pops as loud as the dialog immediately before and after each line spoken, and cuts that even step upon the dialog itself (clipping severely some utterances of ”Yoo Hoo” toward the middle). A colleague of mine, Brad Kay, once spent an entire evening sweating over an audio-editing program, attempting to remix a track for this film clipping out all the pops and smoothing out the abrupt cut-ins. The results were pretty remarkable, and at least one other person has similarly attempted a clean-up on a version that has appeared on the internet. But, if you really want the laughs the gas tries to promise, accept no substitutes. Watch the unaltered edition (below), and place yourself via imagination back with a theater audience of the 1930’s, probably wondering in disbelief how a film could possibly be put together in such amateurish fashion

NEXT WEEK: We’ll take up other forms of audio errors – such as the “Dialog cross-over”, in a subsequent installment, along with the perils which can come from the untrained use of the Bray-Hurd cel.