In his book, Fantasia 2000: Visions of Hope, author John Culhane reflected on Walt Disney’s original plans for Fantasia: “It is our intention to make a new version of Fantasia every year,’ said Walt Disney in 1940. ‘Its pattern is very flexible and fun to work with – not really a concert, not a vaudeville or a revue, but a grand mixture of comedy, fantasy, drama, impressionism, color, sound and epic fury.’”

Sadly, Walt never saw these plans for future Fantasias become a reality. The film didn’t fare well at the box office. By the end of its run, Fantasia generated less than Pinocchio, which was released earlier the same year.

Sadly, Walt never saw these plans for future Fantasias become a reality. The film didn’t fare well at the box office. By the end of its run, Fantasia generated less than Pinocchio, which was released earlier the same year.

With that, Walt put plans for another Fantasia on a shelf, and the studio moved on to other projects. But through the years after its release, there were many others – film and animation historians among them – who wouldn’t let the world forget about Fantasia.

Now celebrating its 85th anniversary, Fantasia has achieved such heights of appreciation as a bold experiment ahead of its time and a shining example of the art of animation, that it’s hard to believe there was a time when the film was considered a disappointment.

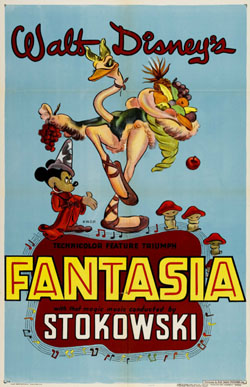

Fantasia grew out of Walt’s love of music, which is seen as early as his Silly Symphony short subjects. In the late thirties, Mickey Mouse’s box-office popularity had declined, and Walt wanted to launch a comeback for his star with The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, based on a 1797 poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe about the title character who finds himself in trouble when he misuses magic.

The poem had been set to music by the composer Paul Dukas, and Walt thought it would be perfect for Mickey. He met with Leopold Stokowski, conductor of The Philadelphia Orchestra, to conduct the music for this potential short subject.

From that meeting came The Concert Feature, which eventually became Fantasia.

Disney, Taylor and Stowkowski

There was: “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor” by Johann Sebastian Bach featuring surrealistic images; “The Nutcracker Suite” by Pyotr Ilich Tchaikovsky had anthropomorphic dances by fish, flowers, and fairies, in place of the traditional Christmas story; there was “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” bringing us Mickey in his, now iconic sorcerer role, trying to keep control of out-of-control brooms; Igor Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring,” set against the formation of the Earth, complete with dinosaurs; “The Pastoral Symphony” by Ludwig van Beethoven brought to life characters from Greek mythology; Amilcare Ponchielli’s “Dance of the Hours” a comic ballet with hippos, ostriches and alligators and “Night on Bald Mountain & Ave Maria” by Modest Mussorgsky, a clash of good and evil featuring one of the studio’s darkest characters, the mountainous Chernabog.

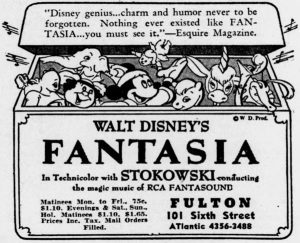

Walt wanted Fantasia treated less like a film and more like a concert. The film was distributed as a “roadshow attraction” (released to a limited number of theaters for a specific period), with an intermission. It was released in “Fantasound” (a pioneering version of today’s surround sound), and programs were provided.

Walt wanted Fantasia treated less like a film and more like a concert. The film was distributed as a “roadshow attraction” (released to a limited number of theaters for a specific period), with an intermission. It was released in “Fantasound” (a pioneering version of today’s surround sound), and programs were provided.

It didn’t connect with audiences, and ideas for other versions of Fantasia were repurposed in a number of Disney’s “package films,” such as Make Mine Music (1946) and Melody Time (1948).

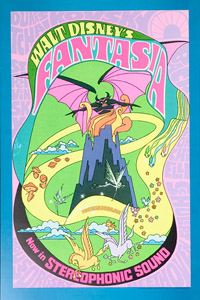

It was in the psychedelic ‘60s, when filmmakers began to experiment, particularly with visuals and music in movies (in films like the Beatles’ animated Yellow Submarine and director Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey), that Fantasia was rediscovered.

Three years after Walt’s death in 1966, Fantasia was re-released to theaters (complete with a now-famous psychedelic poster). A new appreciation for the film from a younger audience began to grow.

In Of Mice and Magic, author Leonard Maltin wrote about this resurgence for Fantasia: “Animator Art Babbitt was asked by some young people who saw the film for the first time if he and his colleagues had used drugs when they made the film 30 years before. ‘Yes, I was on drugs,’ Babbitt replied, “Ex-Lax and Pepto Bismol!’”

In Of Mice and Magic, author Leonard Maltin wrote about this resurgence for Fantasia: “Animator Art Babbitt was asked by some young people who saw the film for the first time if he and his colleagues had used drugs when they made the film 30 years before. ‘Yes, I was on drugs,’ Babbitt replied, “Ex-Lax and Pepto Bismol!’”

In the decades that followed, Fantasia grew in popularity. It would continue to be reissued to theaters, including a newly recorded digital soundtrack at one point and a complete restoration for the film’s 50th anniversary in 1990.

In 1991, Fantasia was released on VHS and went on to sell an impressive 8 million copies worldwide. From this success, Roy E. Disney, Chairman of Feature Animation was able to convince CEO Michael Eisner to move forward with a sequel to Fantasia.

Roy E. Disney had long wanted to realize his Uncle Walt’s dream, which became a reality on January 1, 2000, with the debut of Fantasia 2000.

The culmination of Walt’s original vision demonstrated just how far Fantasia had come. And, in the eighty-five years since its release on November 13, 1940, the world has come to see in Fantasia what Walt once envisioned in his grand plans, as evidenced by a story from the film’s production.

While working on Fantasia, a story artist asked Walt if he felt that they were really using the cartoon medium correctly. According to December 8, 1938, story meeting notes, Walt responded: “This is not the cartoon medium. It should not be limited to cartoons. We have worlds to conquer here.”

• MORE ABOUT FANTASIA: Jim Korkis talks about “Sunflower” [Click Here]

• MORE ABOUT FANTASIA: John Hench on Fantasia [Click Here]

• MORE ABOUT FANTASIA: Greg Ehrbar writes about Fantasia on vinyl records [Click Here]

• ADDITIONAL PLUG: For much more information on Fantasia – please read J.B. Kaufman’s latest book, “Worlds to Conquer: The Art & Making of Walt Disney’s Fantasia”, which goes on sale next Tuesday.