For this month’s Card Catalog, here’s something slightly different. I would like to share with you how one of my favorite animated films introduced me to one of my favorite authors, which then introduced to me a new appreciation for American poetry, which, in turn, made me appreciate my favorite film even more. There are many animation connections along the way and I hope that this may encourage you to follow your own cartoon research and join in on discovering the fun!

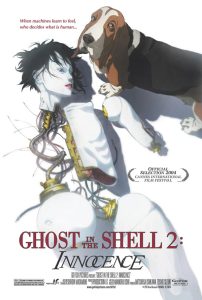

The Ghost in the Shell film franchise was written and directed by Mamoru Oshii, which was in turn, based on the manga of the same name by Masamune Shirow. Ghost in the Shell is a cyberpunk series that often combines philosophical contemplation with dynamic action sequences. The first film released in 1995 asks viewers heavy existential questions like what it means to be a human and how technology may or may not change that definition, especially when jumping to the year 2029.

The Ghost in the Shell film franchise was written and directed by Mamoru Oshii, which was in turn, based on the manga of the same name by Masamune Shirow. Ghost in the Shell is a cyberpunk series that often combines philosophical contemplation with dynamic action sequences. The first film released in 1995 asks viewers heavy existential questions like what it means to be a human and how technology may or may not change that definition, especially when jumping to the year 2029.

Throughout the franchise there are quite a few overt references to various books and religious texts. References are especially prominent in dialogue between characters or as visual motifs. If you’ve seen the episodic sequel series from 2002-2005, Stand Alone Complex, you may be familiar with how the story writes into its first season plot two works by J.D. Salinger, the 1951 novel, The Catcher in the Rye and the 1949 short story, “Laughing Man”.

Sometimes, the literary references can be a little more subtle. In the second film, Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence, the antagonists turn out to be a corporation called LOCUS SOLUS. That name, far from being Latin in origin, is actually the name of a French surrealist book from 1914 written by an eccentric heir who was convinced he was destined for greatness, who instead found notoriety, Raymond Roussel.

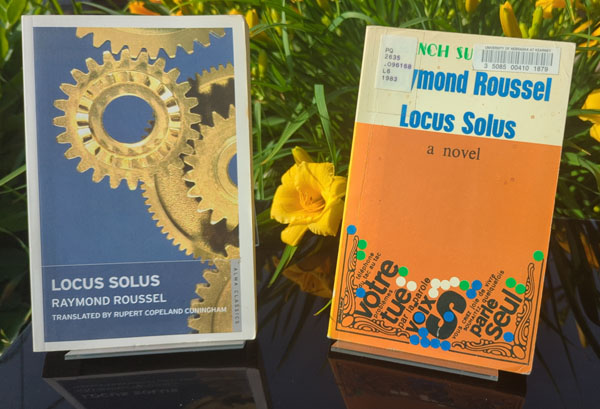

The 1914 novel, LOCUS SOLUS, follows Martial Canterel, a famous inventor and recluse who has, for the first time, invited individuals from around the world into his mansion where he introduces them to one invention after another – each becoming more fantastic as the book goes along. What makes this story special is that each object in the mansion becomes its own short story within a story. Sometimes objects are made of various inventions where Canterel explains their origin and how he came upon them and integrates them into various inventions. If you’re familiar with the aforementioned Innocence, these descriptions may remind you of certain sequences in the film or if you enjoyed the episode of The Venture Brothers, “Blood of the Father, Heart of Steel”, where the decreasing value of a comic book is used a measurement of time to rearrange the episode’s scenes into the correct order – this book is right up your alley.

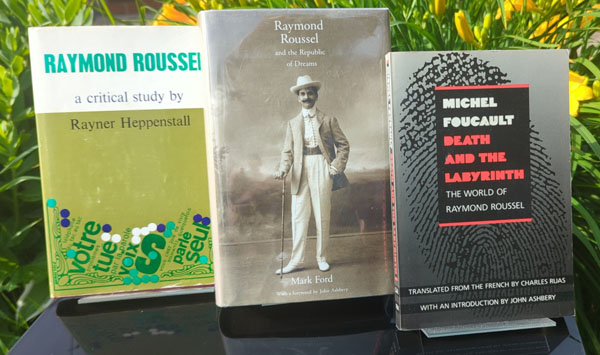

Raymond Roussel was convinced his name would be amongst the greatest writers in history, but he was considered a joke to the surrealist movement of the early 20th century. Heir to a wealthy family, closeted and isolated from most of society, the linguistic rules that Roussel created and meticulously followed allowed for his creativity to blossom in ways unseen since. There exist a few books that cover the uniqueness of Roussel’s poetry, writings, and life. Raymond Roussel and the Republic of Dreams by Mark Ford tackles his life and the meaning in his work, Raymond Roussel: A Critical Study by Raney Heppenstall examines the entirety of Roussel’s output and the contextual changes when he adapted his stories for stage or between short form writings and poetry, and lastly, Death and the Labyrinth: The World of Raymond Roussel by Michel Foucault and translated by Charles Ruas which dives deep into the potential meanings and internal structure of each of Roussel’s works.

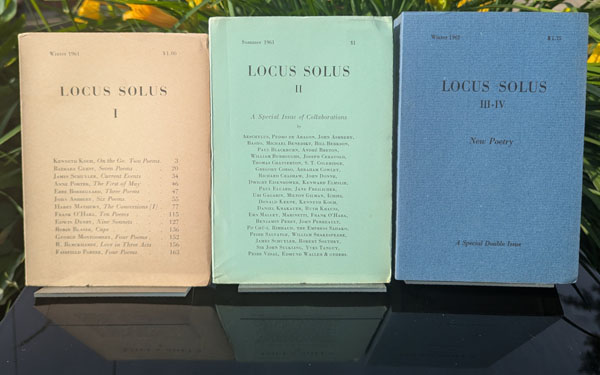

Roussell’s influence was felt in the 1950’s when a group of writers and poets from the New York School of Poetry and the French poetry group, OULIPO, wrote and distributed a series of journals of experimental poetry and short stories inspired by the writings and even borrowing the name from Roussel’s work. Five issues of the LOCUS SOLUS Journal were bound and sold from 1961-1962 with volumes 3 and 4 being bound together. Each volume features a myriad of writers and poets throughout time and the world, but for today’s interest we turn to perhaps one of the most prominent American poets from the 20th century, John Ashberry. He contributed not only a few poems to each of the volumes, but edited volume 3 and 4. He even wrote the introductions for the aforementioned books by Foucault and Ford. You wouldn’t think that the Pulitzer Prize winning poet had many run-ins with animation, but his poem Daffy Duck In Hollywood was written in 1975 and uses Looney Tunes motifs as a means of describing, well, I would argue the frustrations of life, but as with all great surrealist work it reveals something in you.

And that’s the rabbit hole I’ve dug so far. What’s your favorite reference to unexpected other media in cartoons? Have you gone down your own rabbit hole? Thanks for reading and see you next month where I’ll share more books more specifically about the history of animation!