Well into the early innings of our subject, as we move into the first years of the 1940’s – with even MORE Columbia cartoons this week. Despite the outbreak of the War shortly into our survey, and presumed shortages of manpower for available athletes, Baseball somehow survived as a hot ticket, and shows up with recurring frequency in animated references. Today’s lineup is rather evenly split between cartoons entirely devoted to the sport, and others that include only random spot gags, some of them cheaters at that. However, we get at least one certifiable classic from Disney, a creative new perspective on the sport from Terrytoons, and an early Woody Woodpecker which, while not quite polished in its animation, features a good array of new gags.

Porky’s Baseball Broadcast (Warner, Porky Pig, 7/6/40 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir. (for once, taking the billing of “Isadore Freleng” as in some of his earliest cartoons) – Porky takes up the new career of play-by-play radio announcer, for a decisive World Series game, actually billed as between two real-life teams – the Giants and the Red Sox. The game is, however, played on the neutral turf of Yankem Stadium. A newspaper headline can’t resist some verbal puns. The Giants’ starting pitcher is identified as Carl Bubble (reference to Carl Hubbell, real-life pitcher for the Giants, and a Hall of Fame-er). As for the Sox, the headline states they “will depend on Garter”. A side column of the headline story indicates “In case of a tie, duplicate awards will be made.” Porky begins his broadcast over station KWB (for once, not real station KFWB). “Tickets ae selling like hot cakes”, Porky informs the listening audience – and indeed they are, as a chef in the ticket booth pours out batter to create each tucket upon a griddle, serving them to each attendee hot from a spatula. The game sells out, and Porky adds that the “Scalpers are having a big day.” Outside in the parking lot, Indians are seen pursuing patrons with tomahawks. (More visitors from Cleveland?)

Porky’s Baseball Broadcast (Warner, Porky Pig, 7/6/40 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir. (for once, taking the billing of “Isadore Freleng” as in some of his earliest cartoons) – Porky takes up the new career of play-by-play radio announcer, for a decisive World Series game, actually billed as between two real-life teams – the Giants and the Red Sox. The game is, however, played on the neutral turf of Yankem Stadium. A newspaper headline can’t resist some verbal puns. The Giants’ starting pitcher is identified as Carl Bubble (reference to Carl Hubbell, real-life pitcher for the Giants, and a Hall of Fame-er). As for the Sox, the headline states they “will depend on Garter”. A side column of the headline story indicates “In case of a tie, duplicate awards will be made.” Porky begins his broadcast over station KWB (for once, not real station KFWB). “Tickets ae selling like hot cakes”, Porky informs the listening audience – and indeed they are, as a chef in the ticket booth pours out batter to create each tucket upon a griddle, serving them to each attendee hot from a spatula. The game sells out, and Porky adds that the “Scalpers are having a big day.” Outside in the parking lot, Indians are seen pursuing patrons with tomahawks. (More visitors from Cleveland?)

We are introduced to our running gag – a portly gentleman, who seems to be having trouble finding his row and seat, wandering all over the stadium and disturbing seated patrons as he tries to find his location. We’ll get back to him later. Carl Bubble begins warm-up tosses with his catcher. Being a Giant – literally – the towering Bubble merely drops his balls almost vertically into the catcher’s mitt below. Ignoring the previous headline about the Red Sox having someone named Garter, Porky next introduces “Larry O’ Leary from Walla Walla, Washington” as the Sox pitcher – a guy who pitches all their double-headers, because he has two heads. The heads confer in strategy, in the manner of the lyrics of the old song, “Loch Lomond” “You pitch the high ones, and I’ll pitch the low ones.” The umpire makes his entrance – wearing dark glasses, carrying a white cane, and led by a seeing-eye dog. A caricature of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia throws out the first ball, lifted by two assistants to a level above the seat railing, due to the Mayor’s diminutive height. The first batter receives a bat from the bat boy – who flies it in upon real bat wings. (A gag more well-known for its later reappearance in Freleng’s “Baseball Bugs”.) The animators and writers can’t seem to keep track of what teams we’re supposed to be seeing, as we suddenly are presented with a dog pitcher we’ve never seen before, wearing a uniform of the Cubs – who aren’t even in the series! Where did Larry O’ Leary go? Reused animation appears from “Boulevardier From the Bronx” of the gabby turtle catcher who repeatedly gets knocked to the backstop upon catching each pitch. Another “Boulevardier” gag is reused, with a dachshund “stretching” a single into an extra-base home run by extending his expanse between bases – itself stolen from Oswald’s “Soft Ball Game”. Porky remarks that they’ve got the pitcher in a hole already. It is true, as we see the infield with the pitcher’s mound having disappeared, the pitcher instead crawling out from a deep crater in the ground. A pig batter hits the ball so hard, it screams as it flies down the baseline. (This gag appears here with no descriptive dialogue. Freleng would improve on it in “Baseball Bugs” with the announcer’s words, “There goes a screaming liner into left field”). The pig crosses the plate with a home run, observing the instructions of a road sign posted alongside the baseline, reading “Slide Area”. “The pitcher is blowing up”, remarks Porky – and the sound and lights of an offscreen blast indicate he is right again.

We are introduced to our running gag – a portly gentleman, who seems to be having trouble finding his row and seat, wandering all over the stadium and disturbing seated patrons as he tries to find his location. We’ll get back to him later. Carl Bubble begins warm-up tosses with his catcher. Being a Giant – literally – the towering Bubble merely drops his balls almost vertically into the catcher’s mitt below. Ignoring the previous headline about the Red Sox having someone named Garter, Porky next introduces “Larry O’ Leary from Walla Walla, Washington” as the Sox pitcher – a guy who pitches all their double-headers, because he has two heads. The heads confer in strategy, in the manner of the lyrics of the old song, “Loch Lomond” “You pitch the high ones, and I’ll pitch the low ones.” The umpire makes his entrance – wearing dark glasses, carrying a white cane, and led by a seeing-eye dog. A caricature of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia throws out the first ball, lifted by two assistants to a level above the seat railing, due to the Mayor’s diminutive height. The first batter receives a bat from the bat boy – who flies it in upon real bat wings. (A gag more well-known for its later reappearance in Freleng’s “Baseball Bugs”.) The animators and writers can’t seem to keep track of what teams we’re supposed to be seeing, as we suddenly are presented with a dog pitcher we’ve never seen before, wearing a uniform of the Cubs – who aren’t even in the series! Where did Larry O’ Leary go? Reused animation appears from “Boulevardier From the Bronx” of the gabby turtle catcher who repeatedly gets knocked to the backstop upon catching each pitch. Another “Boulevardier” gag is reused, with a dachshund “stretching” a single into an extra-base home run by extending his expanse between bases – itself stolen from Oswald’s “Soft Ball Game”. Porky remarks that they’ve got the pitcher in a hole already. It is true, as we see the infield with the pitcher’s mound having disappeared, the pitcher instead crawling out from a deep crater in the ground. A pig batter hits the ball so hard, it screams as it flies down the baseline. (This gag appears here with no descriptive dialogue. Freleng would improve on it in “Baseball Bugs” with the announcer’s words, “There goes a screaming liner into left field”). The pig crosses the plate with a home run, observing the instructions of a road sign posted alongside the baseline, reading “Slide Area”. “The pitcher is blowing up”, remarks Porky – and the sound and lights of an offscreen blast indicate he is right again.

The Giants now take the mound. At least they remembered to bring Carl Bubble into the game. A standard slow ball is served up. The batter wastes two swings on it, but connects on the third try. Unseen to our eyes, he rounds first, as we see Porky reporting that he is trapped between first and second. We cut to the field, to view the runner, with his foot caught in a giant mousetrap, overacting his part in overly-dramatic fashion, with lines about how “hor-r-r-r-ible” it is. No further new shots are given to us from the field. Instead, a montage of shots we’ve already seen follows, transitioning us to the bottom of the ninth inning. Porky informs us the Giants are down by three runs, but have the bases loaded with two out. The count rises to three balls and two strikes – just as the portly gentleman we’ve seen throughout the cartoon finally finds his assigned seat – directly behind a huge steel girder supporting the grandstand. Porky announces that the Giants have just hit a game-winning grand slam home run, ending the ball game – and neither we nor the portly gentleman have seen a thing but the girder. The scene fades out, then fades back in during late evening hours, the sky now dark and the stadium empty – except for the seated portly fellow, who hasn’t moved a muscle from where we last found him. Finally, his emotions burst, spurring him into action, as he rips out the stadium girder with his bare hands, then begins ripping up seats right and left and tossing them around in frustration, for the iris out.

The Giants now take the mound. At least they remembered to bring Carl Bubble into the game. A standard slow ball is served up. The batter wastes two swings on it, but connects on the third try. Unseen to our eyes, he rounds first, as we see Porky reporting that he is trapped between first and second. We cut to the field, to view the runner, with his foot caught in a giant mousetrap, overacting his part in overly-dramatic fashion, with lines about how “hor-r-r-r-ible” it is. No further new shots are given to us from the field. Instead, a montage of shots we’ve already seen follows, transitioning us to the bottom of the ninth inning. Porky informs us the Giants are down by three runs, but have the bases loaded with two out. The count rises to three balls and two strikes – just as the portly gentleman we’ve seen throughout the cartoon finally finds his assigned seat – directly behind a huge steel girder supporting the grandstand. Porky announces that the Giants have just hit a game-winning grand slam home run, ending the ball game – and neither we nor the portly gentleman have seen a thing but the girder. The scene fades out, then fades back in during late evening hours, the sky now dark and the stadium empty – except for the seated portly fellow, who hasn’t moved a muscle from where we last found him. Finally, his emotions burst, spurring him into action, as he rips out the stadium girder with his bare hands, then begins ripping up seats right and left and tossing them around in frustration, for the iris out.

• Watch PORKY’S BASEBALL BROADCAST by Clicking Here!

Sport Chumpions (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 4/16/41 – I. Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Watch this cartoon for anything but its baseball sequence. It is in many scenes a clever newsreel spoof, covering a wide range of sports, from backyard variety to spectator, in often-clever spot gags. Some standouts are a champion archer who scores a bulls-eye every time – from a distance ot two feet from the target. A swimmer who demonstrates “the crawl” by walking along the bottom of the pool on hands and knees like a baby. A six-day bicycle race that simply goes round and round and round – and round, until the participants stop to say “Monotonous, isn’t it?” A football play described by chart, with directional arrows that become a veritable spider web before the play is completed. (Duck Dodgers must have used this chart to find Planet X.) And a race car driver who is so fast, he remains a blur even when standing still. The film is also notable for early rotoscoping of swimming and diving sequences (though the tracing is overdone and executed in much too literal fashion, losing any resemblance to free-hand animation). But as far as baseball? Nothing but a fallback on Friz’s old standby from “Boulevardier From the Bronx”, of a gabby catcher who endlessly chatters to the pitcher, and repeatedly gets knocked to the backstop on each pitch. Been there, done that.

Sport Chumpions (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 4/16/41 – I. Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Watch this cartoon for anything but its baseball sequence. It is in many scenes a clever newsreel spoof, covering a wide range of sports, from backyard variety to spectator, in often-clever spot gags. Some standouts are a champion archer who scores a bulls-eye every time – from a distance ot two feet from the target. A swimmer who demonstrates “the crawl” by walking along the bottom of the pool on hands and knees like a baby. A six-day bicycle race that simply goes round and round and round – and round, until the participants stop to say “Monotonous, isn’t it?” A football play described by chart, with directional arrows that become a veritable spider web before the play is completed. (Duck Dodgers must have used this chart to find Planet X.) And a race car driver who is so fast, he remains a blur even when standing still. The film is also notable for early rotoscoping of swimming and diving sequences (though the tracing is overdone and executed in much too literal fashion, losing any resemblance to free-hand animation). But as far as baseball? Nothing but a fallback on Friz’s old standby from “Boulevardier From the Bronx”, of a gabby catcher who endlessly chatters to the pitcher, and repeatedly gets knocked to the backstop on each pitch. Been there, done that.

A Hollywood Detour (Screen Gems/Columbia, 1/23/42 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) – Tashlin tries to produce, on the cheap, a cartoon echoing the style of his former (and future) employers at Warner Brothers. It is no equivalent to “Hollywood Steps Out”, and shows its budgetary cuts, with extended scenes depending only on panning backgrounds with no animation, shots repeated three times in the same picture, and substantial use of caricature animation and sequences seen in previous Columbia pictures, including several scenes from “Hollywood Picnic”, seen here last week. Included are shots with slight revision from the baseball sequence of such film. Joe E, Brown is again shown pitching, but delivers up a slow ball, which, in a new close-up, is outrun by a passing snail. The Marx Brothers are again at bat, but address the ball in slow motion as well, which changes to a whirling spin as the ball gets past them, driving the three of them like a drill into a hole in the ground. The sequence ends with a verbatim repeat of the catch of the ball by the Three Stooges, although superior sound and vocal effects from the original film are omitted from the reused shot.

A Hollywood Detour (Screen Gems/Columbia, 1/23/42 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) – Tashlin tries to produce, on the cheap, a cartoon echoing the style of his former (and future) employers at Warner Brothers. It is no equivalent to “Hollywood Steps Out”, and shows its budgetary cuts, with extended scenes depending only on panning backgrounds with no animation, shots repeated three times in the same picture, and substantial use of caricature animation and sequences seen in previous Columbia pictures, including several scenes from “Hollywood Picnic”, seen here last week. Included are shots with slight revision from the baseball sequence of such film. Joe E, Brown is again shown pitching, but delivers up a slow ball, which, in a new close-up, is outrun by a passing snail. The Marx Brothers are again at bat, but address the ball in slow motion as well, which changes to a whirling spin as the ball gets past them, driving the three of them like a drill into a hole in the ground. The sequence ends with a verbatim repeat of the catch of the ball by the Three Stooges, although superior sound and vocal effects from the original film are omitted from the reused shot.

Wacky Wigwams (Screen Gems/Columbia, Color Rhapsody, 2/22/42 – Alec Geiss, dir.) – A collection of random spot gags on Native Americans – more or less Columbia’s answer to such films as Warner’s “Sweet Sioux” or Walter Lantz’s “Syncopated Sioux”. Again, seemingly attempting to save on budget, most of the best action is saved for a buffalo hunt in the second half, with the first half often devoted to panning backgrounds or scenes with limited motion. Some of the better gags include meeting Chief Thunder Cloud – a chieftain consisting only of black water vapor. A witch doctor appears to be concocting a brew – but responds in a polite British accent that it is only a spot of tea. An Avery-style running gag features a rainmaker whose snake dance to bring rain accomplishes nothing but to carve a deep circular troth in the dry ground. But he achieves his results, by taking time out to polish an old Tin Lizzie – and of course, the minute you clean up a car, here comes the rain. Perhaps the best gag is another Avery-inspired lift, “taking off” from the strip-teasing lizard in Avery’s “Cross-Country Detours”, with a “Cherokee Strip”, featuring a well-drawn and probably rotoscoped Indian maiden peeling, but our view is repeatedly obscured by slides blocking the screen, calling a Dr. Schmaltz to come to the box office. By the time Schmaltz is found, all we have left to see is the bare leg of the girl disappearing off the screen, with her clothes neatly piled in the center of our view. All the narrator can do is grumble at what we missed.

Wacky Wigwams (Screen Gems/Columbia, Color Rhapsody, 2/22/42 – Alec Geiss, dir.) – A collection of random spot gags on Native Americans – more or less Columbia’s answer to such films as Warner’s “Sweet Sioux” or Walter Lantz’s “Syncopated Sioux”. Again, seemingly attempting to save on budget, most of the best action is saved for a buffalo hunt in the second half, with the first half often devoted to panning backgrounds or scenes with limited motion. Some of the better gags include meeting Chief Thunder Cloud – a chieftain consisting only of black water vapor. A witch doctor appears to be concocting a brew – but responds in a polite British accent that it is only a spot of tea. An Avery-style running gag features a rainmaker whose snake dance to bring rain accomplishes nothing but to carve a deep circular troth in the dry ground. But he achieves his results, by taking time out to polish an old Tin Lizzie – and of course, the minute you clean up a car, here comes the rain. Perhaps the best gag is another Avery-inspired lift, “taking off” from the strip-teasing lizard in Avery’s “Cross-Country Detours”, with a “Cherokee Strip”, featuring a well-drawn and probably rotoscoped Indian maiden peeling, but our view is repeatedly obscured by slides blocking the screen, calling a Dr. Schmaltz to come to the box office. By the time Schmaltz is found, all we have left to see is the bare leg of the girl disappearing off the screen, with her clothes neatly piled in the center of our view. All the narrator can do is grumble at what we missed.

For our present purposes, a sequence shows a pow-wow leading to a meeting of various tribes, including the Blackfeet (heels of such color visible from out the canvas of a wigwam), the Pawnee (shown by a teepee decked out with pawnbroker’s globes and signs), and of course, the Cleveland Indians, on a baseball diamond.

Uncle Joey Comes To Town (Terrytoons/Fox, 9/19/41 – Mannie Davis, dir.) – An above-par and well-animated black and white Terrytoon of the day, featuring a return for a character previously introduced in a color episode – a mouse known as “Uncle Joey” who in the prior film bearing his name is established as residing in a toy shop, such that he is a favorite of the young mice by bringing them presents therefrom. He is named “Joey’ because his facial features, especially his mouth, bear string resemblance to those of Joe E. Brown, who we’ve encountered before in this series for his well-known love of baseball. The first cartoon feauring the character made no references to his baseball association – but this second appearance well makes up for it, by concentrating on the subject, as Joey arrives in a wind-up toy car for a visit with a large family of mice residing in the walls of a swank mansion, and presents all the youths with miniature baseball caps and uniforms. They all proceed to their favorite baseball diamond – the top of a tablecloth-covered long dinner table in the dining room, once a butler and a small cat who closely resembles Disney’s Figaro step away.

Uncle Joey Comes To Town (Terrytoons/Fox, 9/19/41 – Mannie Davis, dir.) – An above-par and well-animated black and white Terrytoon of the day, featuring a return for a character previously introduced in a color episode – a mouse known as “Uncle Joey” who in the prior film bearing his name is established as residing in a toy shop, such that he is a favorite of the young mice by bringing them presents therefrom. He is named “Joey’ because his facial features, especially his mouth, bear string resemblance to those of Joe E. Brown, who we’ve encountered before in this series for his well-known love of baseball. The first cartoon feauring the character made no references to his baseball association – but this second appearance well makes up for it, by concentrating on the subject, as Joey arrives in a wind-up toy car for a visit with a large family of mice residing in the walls of a swank mansion, and presents all the youths with miniature baseball caps and uniforms. They all proceed to their favorite baseball diamond – the top of a tablecloth-covered long dinner table in the dining room, once a butler and a small cat who closely resembles Disney’s Figaro step away.

We are treated to a new angle on the sport from a mouse-eye point of view. Instead of bats, the mice use spoons, forks, etc. from the dinner table. Instead of baseballs, olives make a suitable substitute. Home “plate” is just that – one of the china plates on the table, with the other bases consisting of plates as well. The playing field extends to the end of the table, and ends where the tablecloth drops off to the floor. An egg-strainer serves as a catcher’s mask. Bleacher seating is provided atop the back of the seat cushions of the human-sized chairs.

The mice choose who will pitch first by having one mouse bend over, extending his tail high into the air, while the captains of the two teams play a game of hand-over-hand grabs of the tail like a bat, topmost grab winning the right to bat first. The first pitch of the game is hit by the batter, but the olive disappears into Joey’s wide mouth and down his throat. Joey, acting as umpire, calls, “Ball one!” (Perhaps the call should have been “Foul”.) The next pitch is also hit, but fairly. It is caught, however, by one of the fielders (should we call them field mice?) launching another into the air by jumping upon the bowl of a spoon while the other stands on the handle. The airborne mouse easily makes the catch. It seems, though, that there is no immediate call of out. Instead, the olive is tossed to first, but the runner passes first, and tries to head for second. His progress is stopped when the first baseman steps upon his tail, holding the runner in place long enough to bend to make a tag. Out! The next batter uses a fork instead of a spoon to bat, and accomplishes what might be called the equivalent of a bunt, spearing the tossed olive upon the end of the fork’s tines. As the runner drops the fork to run to first, the catcher picks up the fork by the handle, and gives it a strong flip of the wrist, dislodging the olive and sending it whizzing toward first base. The runner slides toward the plate that serves as first, catching hold of its edge and sliding somewhat past the bag, spinning the entire plate and moving the baseman out of range to make a clean catch of the tossed olive, and also leaving him somewhat dizzy fron the spinning. The runner passes second, but gets caught up between second and third. The old burrow-into-the-ground from past Terry/Van Beuren efforts appears again, but with a new clever twist. Having no ground to burrow into, the runner bursts through the fabric of the tablecloth, traveling below it for part of the way to third base. He reappears again above the surface through a hole in the fabric, coming up under an inverted wine glass. Carrying the glass over himself all the way to third base, the mouse avoids any possibility of getting tagged with the olive before touching his feet onto third, then makes distorted faces at the other team through the curved glass. A new batter receives the old slow ball, which somehow seems funnier than usual when performed by an olive. After several false swings, the batter is able to pull the floating ball down to his height, and sock it with a butter knife. It sails off the table – as does the outfielder, sliding down the end of the tablecloth, and having the olive bounce off his head. The runner rounds the bases, and one of his teammates assists by spreading a bed of mustard along the baseline leading to home plate, providing the runner with a comfortable means to slide.

The mice choose who will pitch first by having one mouse bend over, extending his tail high into the air, while the captains of the two teams play a game of hand-over-hand grabs of the tail like a bat, topmost grab winning the right to bat first. The first pitch of the game is hit by the batter, but the olive disappears into Joey’s wide mouth and down his throat. Joey, acting as umpire, calls, “Ball one!” (Perhaps the call should have been “Foul”.) The next pitch is also hit, but fairly. It is caught, however, by one of the fielders (should we call them field mice?) launching another into the air by jumping upon the bowl of a spoon while the other stands on the handle. The airborne mouse easily makes the catch. It seems, though, that there is no immediate call of out. Instead, the olive is tossed to first, but the runner passes first, and tries to head for second. His progress is stopped when the first baseman steps upon his tail, holding the runner in place long enough to bend to make a tag. Out! The next batter uses a fork instead of a spoon to bat, and accomplishes what might be called the equivalent of a bunt, spearing the tossed olive upon the end of the fork’s tines. As the runner drops the fork to run to first, the catcher picks up the fork by the handle, and gives it a strong flip of the wrist, dislodging the olive and sending it whizzing toward first base. The runner slides toward the plate that serves as first, catching hold of its edge and sliding somewhat past the bag, spinning the entire plate and moving the baseman out of range to make a clean catch of the tossed olive, and also leaving him somewhat dizzy fron the spinning. The runner passes second, but gets caught up between second and third. The old burrow-into-the-ground from past Terry/Van Beuren efforts appears again, but with a new clever twist. Having no ground to burrow into, the runner bursts through the fabric of the tablecloth, traveling below it for part of the way to third base. He reappears again above the surface through a hole in the fabric, coming up under an inverted wine glass. Carrying the glass over himself all the way to third base, the mouse avoids any possibility of getting tagged with the olive before touching his feet onto third, then makes distorted faces at the other team through the curved glass. A new batter receives the old slow ball, which somehow seems funnier than usual when performed by an olive. After several false swings, the batter is able to pull the floating ball down to his height, and sock it with a butter knife. It sails off the table – as does the outfielder, sliding down the end of the tablecloth, and having the olive bounce off his head. The runner rounds the bases, and one of his teammates assists by spreading a bed of mustard along the baseline leading to home plate, providing the runner with a comfortable means to slide.

The game moves into late innings, with various mice scoring hit after hit against the nervous pitcher, who seems to have lost control of the situation. A socked olive hits the back cushion of one of the chairs serving as seating for the spectators, toppling a whole row of mice backwards and onto the floor. Several hits fly high, through the windows of a cuckoo clock ,ade to resemble a German cottage. The angry cuckoo bird appears on his perch to protest, but gets hit with an olive too. He dives upon the mice, causing the game to be abruptly abandoned, and the mice to flee into their mousehole, followed by the wooden bird – just as the cat returns to the room to observe the uproar. After a brief pause, several mice attempt to escape from the bird’s wrath by fleeing the hole. As they emerge, the cat attempts to swallow them, snapping at them with his jaws, but missing. The third figure that emerges from the hole is not so lucky, the cat snapping it up in a blur, and quickly swallowing. Sounds from within the cat tell us that he picked the wrong target, as loud “cuckoo”s emanate from the cat’s belly. He has swallowed the fake bird instead, which has the effect of briefly causing the cat to flap his arms and fly. Several mice, now back upon the dinner table, duck under the tablecloth and run, upsetting numerous plates along the way. The cat attempts to run alongside the table to catch the plates one-by-one as they fall, but trips when he reaches table’s end, smashing the stack he has rescued. Joey laughs at him from high upon a china shelf encircling the room, and swipes a routine from Jerry the Mouse in his recent debut for MGM in “Puss Gets the Boot” (if you’re going to steal, steal from the best). Joey begins toppling over nearly every plate lining the room’s rafters, until the cat is carrying a stack about ten feet high. Then, he hops between the shelf and the topmost of the cat’s plates, kicking the plates with his feet. CRASH!! As with Tom in the MGM classic, the cat gets the blame from the butler, and is tossed out of his happy home. Uncle Joey takes his leave of the abode, exiting a mousehole toward his car, but not realizing the cat is still outside, and waiting. With a tip of his hat, Joey cautiously steps backwards, gains the footing of his car seat parked just below the street curb, and floors the accelerator, roaring down the street into the distance, with the cat just one step behind him.

The game moves into late innings, with various mice scoring hit after hit against the nervous pitcher, who seems to have lost control of the situation. A socked olive hits the back cushion of one of the chairs serving as seating for the spectators, toppling a whole row of mice backwards and onto the floor. Several hits fly high, through the windows of a cuckoo clock ,ade to resemble a German cottage. The angry cuckoo bird appears on his perch to protest, but gets hit with an olive too. He dives upon the mice, causing the game to be abruptly abandoned, and the mice to flee into their mousehole, followed by the wooden bird – just as the cat returns to the room to observe the uproar. After a brief pause, several mice attempt to escape from the bird’s wrath by fleeing the hole. As they emerge, the cat attempts to swallow them, snapping at them with his jaws, but missing. The third figure that emerges from the hole is not so lucky, the cat snapping it up in a blur, and quickly swallowing. Sounds from within the cat tell us that he picked the wrong target, as loud “cuckoo”s emanate from the cat’s belly. He has swallowed the fake bird instead, which has the effect of briefly causing the cat to flap his arms and fly. Several mice, now back upon the dinner table, duck under the tablecloth and run, upsetting numerous plates along the way. The cat attempts to run alongside the table to catch the plates one-by-one as they fall, but trips when he reaches table’s end, smashing the stack he has rescued. Joey laughs at him from high upon a china shelf encircling the room, and swipes a routine from Jerry the Mouse in his recent debut for MGM in “Puss Gets the Boot” (if you’re going to steal, steal from the best). Joey begins toppling over nearly every plate lining the room’s rafters, until the cat is carrying a stack about ten feet high. Then, he hops between the shelf and the topmost of the cat’s plates, kicking the plates with his feet. CRASH!! As with Tom in the MGM classic, the cat gets the blame from the butler, and is tossed out of his happy home. Uncle Joey takes his leave of the abode, exiting a mousehole toward his car, but not realizing the cat is still outside, and waiting. With a tip of his hat, Joey cautiously steps backwards, gains the footing of his car seat parked just below the street curb, and floors the accelerator, roaring down the street into the distance, with the cat just one step behind him.

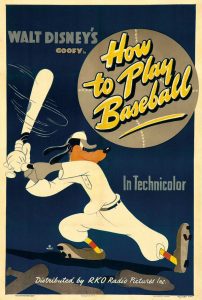

How To Play Baseball (Disney/RKO. Goofy, 9/4/42 – Jack Kinney, dir.) – A landmark for the Goofy “How To” films, marking the Goof’s first venture into professional team sports, and our first-ever introduction to not just one Goof, but two entire teams of Goofs, plus umpire! A new narrator, slightly less cultured and uppity than the usual one and with a voice more resembling a professional broadcaster, presides over the instruction. The film is divided into halves, the first instructing upon the nature of the game, and the latter showing us the drama of a real World Series game in progress. In the instructional half, the narrator observes that play starts when the batter hits the ball – but strangely enough, the pitcher tries to keep the ball from being hit- which probably accounts for the principal criticisms about the pacing of the game by those who are not baseball fans. (And dare we talk about cricket?) In describing the standard uniform, the narrator observes that “The socks are what the team is named after.” He further observes that “The game is quite simple, as there are only nine players to watch at one time.” (Oh, yeah?) Simplicity is demonstrated diagrammatically, in a shot closely resembling the football play depicted in Warner’s “Sport Chumpions” above. After the maze of dotted lines and arrows covers the diagram, the narrator describes the outcome of the play: “The runner is out, or safe, or either, or neither, or both.”

How To Play Baseball (Disney/RKO. Goofy, 9/4/42 – Jack Kinney, dir.) – A landmark for the Goofy “How To” films, marking the Goof’s first venture into professional team sports, and our first-ever introduction to not just one Goof, but two entire teams of Goofs, plus umpire! A new narrator, slightly less cultured and uppity than the usual one and with a voice more resembling a professional broadcaster, presides over the instruction. The film is divided into halves, the first instructing upon the nature of the game, and the latter showing us the drama of a real World Series game in progress. In the instructional half, the narrator observes that play starts when the batter hits the ball – but strangely enough, the pitcher tries to keep the ball from being hit- which probably accounts for the principal criticisms about the pacing of the game by those who are not baseball fans. (And dare we talk about cricket?) In describing the standard uniform, the narrator observes that “The socks are what the team is named after.” He further observes that “The game is quite simple, as there are only nine players to watch at one time.” (Oh, yeah?) Simplicity is demonstrated diagrammatically, in a shot closely resembling the football play depicted in Warner’s “Sport Chumpions” above. After the maze of dotted lines and arrows covers the diagram, the narrator describes the outcome of the play: “The runner is out, or safe, or either, or neither, or both.”

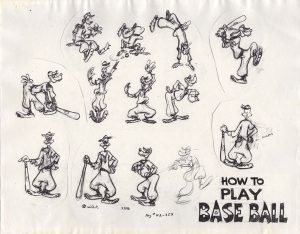

Pitching skills are demonstrated. The windup propels the Goofy pitcher into the air as if his arm were a helicopter blade. He falls upside down in a heap upon the mound, and only manages to propel the ball to the plate by a snap of the sphere between his thumb and forefinger. The batter makes himself look like a professional ball player, by scooping up handfuls of dirt and mud and covering his nice clean uniform in it – right up to his armpits. The pitcher demonstrates three varieties of curve ball – the inside curve and the outside curve (dodged by the batter by bending his midriff into a U in opposite directions, similar to the dachshund in Oswald’s “Soft Ball Game”), and the drop ball (which performs a new twist, dropping vertically to burrow its way into the ground just before the plate, tunneling under, and then reappearing from the earth behind the plate to fly into the catcher’s mitt). The straight-ball spinner is next delivered. Its rotation drills through the center of the batter’s bat, severing it in two, and sending wood strips flying onto the batter’s head, that leave him with a wig of curly golden locks. The unavoidable slow ball is next, with no particular new innovation for payoff gag. A spit ball spits right in the batter’s face to “dampen his spirits”. Then, the fireball, which reduces the batter’s lumber to a burnt-out matchstick.

Pitching skills are demonstrated. The windup propels the Goofy pitcher into the air as if his arm were a helicopter blade. He falls upside down in a heap upon the mound, and only manages to propel the ball to the plate by a snap of the sphere between his thumb and forefinger. The batter makes himself look like a professional ball player, by scooping up handfuls of dirt and mud and covering his nice clean uniform in it – right up to his armpits. The pitcher demonstrates three varieties of curve ball – the inside curve and the outside curve (dodged by the batter by bending his midriff into a U in opposite directions, similar to the dachshund in Oswald’s “Soft Ball Game”), and the drop ball (which performs a new twist, dropping vertically to burrow its way into the ground just before the plate, tunneling under, and then reappearing from the earth behind the plate to fly into the catcher’s mitt). The straight-ball spinner is next delivered. Its rotation drills through the center of the batter’s bat, severing it in two, and sending wood strips flying onto the batter’s head, that leave him with a wig of curly golden locks. The unavoidable slow ball is next, with no particular new innovation for payoff gag. A spit ball spits right in the batter’s face to “dampen his spirits”. Then, the fireball, which reduces the batter’s lumber to a burnt-out matchstick.

A still frame from HOW TO PLAY BASEBALL (1942) directed by Jack Kinney, animation by Ward Kimball, layout by Al Zinnen; Prod. #2296, scene 43.1; ©Disney

More upset than ever, the pitcher launches a ball carelessly toward the next batter – and beans him, allowing for a stumbling free trip to first base. Sweat now pours off the pitcher’s brow and a flood from under his cap, and his next pitch doesn’t seem to have the usual zing. The new batter responds to it by bunting. Three infielders converge at the point where the ball will drop, but smash into one another. They all fall backwards in prone position, and the ball lands atop the converged toes of their three sets of shoes. The three fielders knot themselves up into a braid, and unite in tossing the ball to first – but too late. The runner arrives safely, and the bases are loaded. Both pitcher and new batter sweat profusely. “A half-million dollars and the world series hinge on this pitch.” POW!! A terrific hit, which tears the cover off the ball. An outfielder positions himself under the unwinding threads of the ball’s center, acquires one end of the thread in his mitt, but lets the rest of the unraveled ball fall in endless loops around his feet. He dropped it. As the men already on base easily score, the batter has his share of trouble, as his spikes keep catching in the bags of each base as he passes over them, elevating one foot with the extra height of three bags. As for the outfielder, he is desperately attempting to wind the thread back into the shape of a baseball. He tries to throw what he has rewound, but the thrown portion unravels again, while the unwound portion catches on the fielder’s feet and spins him around like a top. No choice but to pick up all the loose thread like the tresses of an overly-long dress, and attempt to outrace the runner to home plate. “It’s going to be close”, and both runner and fielder slide from opposite directions, crashing in a collision directly before the home plate umpire. As both runner and batter lay prone at equal distances from the plate, the umpire bends down for a closer look, and tries to sort things out. The “impartial pillar of judicial dignity, whose word is law”, declares, “He’s out!” The runner instantly starts jawing at the umpire, protesting the call. Intimidated, the umpire changes the call to “He’s safe!” Now the fielder voices his own protest. Before any further changes can be made, both benches clear from the dugouts, and two teams join in mauling the umpire in a fight cloud, complete with flying bats, balls, and pop bottles. The narrator closes upon this scene, as naturally befitting the game. “Free speech! That great American pribilege is thoroughly enjoyed by players and spectators alike. That’s why the national sport will always be that good old American game – baseball!”

More upset than ever, the pitcher launches a ball carelessly toward the next batter – and beans him, allowing for a stumbling free trip to first base. Sweat now pours off the pitcher’s brow and a flood from under his cap, and his next pitch doesn’t seem to have the usual zing. The new batter responds to it by bunting. Three infielders converge at the point where the ball will drop, but smash into one another. They all fall backwards in prone position, and the ball lands atop the converged toes of their three sets of shoes. The three fielders knot themselves up into a braid, and unite in tossing the ball to first – but too late. The runner arrives safely, and the bases are loaded. Both pitcher and new batter sweat profusely. “A half-million dollars and the world series hinge on this pitch.” POW!! A terrific hit, which tears the cover off the ball. An outfielder positions himself under the unwinding threads of the ball’s center, acquires one end of the thread in his mitt, but lets the rest of the unraveled ball fall in endless loops around his feet. He dropped it. As the men already on base easily score, the batter has his share of trouble, as his spikes keep catching in the bags of each base as he passes over them, elevating one foot with the extra height of three bags. As for the outfielder, he is desperately attempting to wind the thread back into the shape of a baseball. He tries to throw what he has rewound, but the thrown portion unravels again, while the unwound portion catches on the fielder’s feet and spins him around like a top. No choice but to pick up all the loose thread like the tresses of an overly-long dress, and attempt to outrace the runner to home plate. “It’s going to be close”, and both runner and fielder slide from opposite directions, crashing in a collision directly before the home plate umpire. As both runner and batter lay prone at equal distances from the plate, the umpire bends down for a closer look, and tries to sort things out. The “impartial pillar of judicial dignity, whose word is law”, declares, “He’s out!” The runner instantly starts jawing at the umpire, protesting the call. Intimidated, the umpire changes the call to “He’s safe!” Now the fielder voices his own protest. Before any further changes can be made, both benches clear from the dugouts, and two teams join in mauling the umpire in a fight cloud, complete with flying bats, balls, and pop bottles. The narrator closes upon this scene, as naturally befitting the game. “Free speech! That great American pribilege is thoroughly enjoyed by players and spectators alike. That’s why the national sport will always be that good old American game – baseball!”

• Watch Goofy in HOW TO PLAY BASEBALL by clicking HERE.

The Screwball (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 2/15/43 – Alex Lovy, dir.) – Lovy had only recently taken the driver’s seat as director on this series after initial efforts helmed by Lantz himself, and had managed to slightly streamline Woody in design and color to a figure more closely resembling how he would be known during a good part of the decade. However, there remains a certain roughness to draftsmanship in Lovy’s productions during this period, with somewhat stilted movement, often irregular inking and painting, and some misshapen facial features on supporting characters. These flaws were likely the result of budget cuts and/or wartime labor shortages, given the comparatively flawless draftsmanship of earlier Lovy efforts such as “Kittens’ Mittens”. Nevertheless, despite its technical shortcomings, this episode fares well in its material and timing, and still remains a fun view.

The Screwball (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 2/15/43 – Alex Lovy, dir.) – Lovy had only recently taken the driver’s seat as director on this series after initial efforts helmed by Lantz himself, and had managed to slightly streamline Woody in design and color to a figure more closely resembling how he would be known during a good part of the decade. However, there remains a certain roughness to draftsmanship in Lovy’s productions during this period, with somewhat stilted movement, often irregular inking and painting, and some misshapen facial features on supporting characters. These flaws were likely the result of budget cuts and/or wartime labor shortages, given the comparatively flawless draftsmanship of earlier Lovy efforts such as “Kittens’ Mittens”. Nevertheless, despite its technical shortcomings, this episode fares well in its material and timing, and still remains a fun view.

A professional baseball game is about to begin at the local stadium. However, with a match-up of the “Droops vs. Drips” (guaranteed a good game to the last Drip, playing on the famous Maxwell House Coffee slogan), it’s hard to choose a side to be a booster for. Just inside the ballpark, a cop patrols along the outfield fence. Outside, the usual crowd of freeloaders lines the fence in search of well-placed knotholes for viewing. And those that can’t find one make their own, by bringing along their own drills, one of which emerges through the wood right under the cop’s nose. The officer has an absolutely sadistic sense of humor, and begins to violently poke the end of his Billy club through every fence hole he can spot, giving every spectator on the other side a painful black eye (if not immediate blindness). The last knothole along the row, however, produces an unexpected result for the cop. As his club is thrust through the hole, the sound of loud pecking is heard, with his hand and the club vibrating violently. The cop pulls back his club for inspection, finding it reduced to a sharpened pencil point. Then the pecking begins again. A series of small holes are popped out of the fence wood, tracing the outline of the silhouette of a standing woodpecker. Enter Woody, opening up the fence image like a hinged door to invite himself inside the park. The cop quickly grabs the cocky bird up by the neck. “So, trying to get in on your nerve. Well, you’re going out on your ear!” He hurls Woody over the fence, landing him inside the muzzle of a park cannon commemorating some past battle. Our hero extracts himself from the barrel with some effort, then notices the cop, now at the entrance gate to the stadium, admitting a kid for free for returning a baseball hit over the fence. Thinking quickly, Woody lifts a heavy cannonball off the pedestal supporting the cannon display, and lugs it over to the cop. He tosses the iron ball at the officer, who extends his hands, expecting to catch a lightweight ball of twine and cork. His hands are driven straight into the ground by the unexpected heavy load, and he struggles with his top half completely buried in the ground, as Woody calmly prances his way into the stadium unmolested.

A professional baseball game is about to begin at the local stadium. However, with a match-up of the “Droops vs. Drips” (guaranteed a good game to the last Drip, playing on the famous Maxwell House Coffee slogan), it’s hard to choose a side to be a booster for. Just inside the ballpark, a cop patrols along the outfield fence. Outside, the usual crowd of freeloaders lines the fence in search of well-placed knotholes for viewing. And those that can’t find one make their own, by bringing along their own drills, one of which emerges through the wood right under the cop’s nose. The officer has an absolutely sadistic sense of humor, and begins to violently poke the end of his Billy club through every fence hole he can spot, giving every spectator on the other side a painful black eye (if not immediate blindness). The last knothole along the row, however, produces an unexpected result for the cop. As his club is thrust through the hole, the sound of loud pecking is heard, with his hand and the club vibrating violently. The cop pulls back his club for inspection, finding it reduced to a sharpened pencil point. Then the pecking begins again. A series of small holes are popped out of the fence wood, tracing the outline of the silhouette of a standing woodpecker. Enter Woody, opening up the fence image like a hinged door to invite himself inside the park. The cop quickly grabs the cocky bird up by the neck. “So, trying to get in on your nerve. Well, you’re going out on your ear!” He hurls Woody over the fence, landing him inside the muzzle of a park cannon commemorating some past battle. Our hero extracts himself from the barrel with some effort, then notices the cop, now at the entrance gate to the stadium, admitting a kid for free for returning a baseball hit over the fence. Thinking quickly, Woody lifts a heavy cannonball off the pedestal supporting the cannon display, and lugs it over to the cop. He tosses the iron ball at the officer, who extends his hands, expecting to catch a lightweight ball of twine and cork. His hands are driven straight into the ground by the unexpected heavy load, and he struggles with his top half completely buried in the ground, as Woody calmly prances his way into the stadium unmolested.

Woody searches for a choice seat in his own way, pecking upwards through the floorboards of the grandstand to survey the available seating. The sequence which follows seems so similar in mood to that of a Columbia live-action short of a preceding season, that one may indeed wonder if the writers here were not inspired by it – Charley Chase’s masterpiece, “The Heckler”, in which he portrays the world’s most obnoxious sports fan. Woody spots a vacant chair, upon the folding cushion of which rest the toes of a patron dozing in the seat behind, awaiting the start of the game. Woody plops himself down upon the forward seat’s cushion, trapping the toes of the man behind him. “Get your seat off of my feet!”, shouts the irate man. Woody stands up briefly to release him, as the man surveys his toes, bent at right angles to his insteps. Retaking his seat, Woody remarks, “What a view!” Along comes a long tall Texan, wearing a ten-gallon hat, who sits down in front of him. Woody can’t see a thing past the Stetson. “Hey, Herbie! Remove the derby”, asks Woody politely. The cowboy obliges, revealing an expanse of hair concealed under the hat brim, even wider and taller than the hat itself. Well, asking anything further will obviously accomplish nothing, so Woody solves the problem with his own wits. Producing a lawn mower from nowhere, Woody performs barber’s duties, by carving a path with the mower right through the middle of the cowboy’s locks, down to the bare scalp. Woody not only has a clear view, but a place to rest his elbows as he leans forward to peer over, resting his arms upon the cowboy’s bald dome. Next, a vendor passes Woody’s row, carrying a load of soda pop for sale. As he passes Woody’s seat. Woody snatches a whole crate of a dozen pop bottles from under the vendor’s arm. Resting the crate in his own lap, Woody pulls out one of the bottles for his refreshment. But he is without a bottle opener, and struggles to pry the stubborn cap off upon the top edge of his seat. Then, another inspiration strikes Woody’s eyes. A country hick, wearing an old straw hat, sits in somewhat of a stupor in a row behind him – open mouthed, and displaying two large front buck teeth. Woody slips his bottle between the unnoticing hick’s jaws, and pries the cap off upon his buck teeth. Finally ready to settle in, Woody tries to raise the bottle to his lips, but discovers the cop, standing in the aisle and looming over him menacingly. Again thinking quickly, Woody places his thumb over the open top of the bottle, and shakes the bottle’s contents vigorously. “Have some pop, cop?”. asks Woody, handing the bottle to the officer. The carbonated contents bubble up, and spew out in a torrent, right in the officer’s face. “No stopper, copper!”, quips Woody, giving his laugh, and making a quick getaway before the cop can dry his soaked eyes.

Woody searches for a choice seat in his own way, pecking upwards through the floorboards of the grandstand to survey the available seating. The sequence which follows seems so similar in mood to that of a Columbia live-action short of a preceding season, that one may indeed wonder if the writers here were not inspired by it – Charley Chase’s masterpiece, “The Heckler”, in which he portrays the world’s most obnoxious sports fan. Woody spots a vacant chair, upon the folding cushion of which rest the toes of a patron dozing in the seat behind, awaiting the start of the game. Woody plops himself down upon the forward seat’s cushion, trapping the toes of the man behind him. “Get your seat off of my feet!”, shouts the irate man. Woody stands up briefly to release him, as the man surveys his toes, bent at right angles to his insteps. Retaking his seat, Woody remarks, “What a view!” Along comes a long tall Texan, wearing a ten-gallon hat, who sits down in front of him. Woody can’t see a thing past the Stetson. “Hey, Herbie! Remove the derby”, asks Woody politely. The cowboy obliges, revealing an expanse of hair concealed under the hat brim, even wider and taller than the hat itself. Well, asking anything further will obviously accomplish nothing, so Woody solves the problem with his own wits. Producing a lawn mower from nowhere, Woody performs barber’s duties, by carving a path with the mower right through the middle of the cowboy’s locks, down to the bare scalp. Woody not only has a clear view, but a place to rest his elbows as he leans forward to peer over, resting his arms upon the cowboy’s bald dome. Next, a vendor passes Woody’s row, carrying a load of soda pop for sale. As he passes Woody’s seat. Woody snatches a whole crate of a dozen pop bottles from under the vendor’s arm. Resting the crate in his own lap, Woody pulls out one of the bottles for his refreshment. But he is without a bottle opener, and struggles to pry the stubborn cap off upon the top edge of his seat. Then, another inspiration strikes Woody’s eyes. A country hick, wearing an old straw hat, sits in somewhat of a stupor in a row behind him – open mouthed, and displaying two large front buck teeth. Woody slips his bottle between the unnoticing hick’s jaws, and pries the cap off upon his buck teeth. Finally ready to settle in, Woody tries to raise the bottle to his lips, but discovers the cop, standing in the aisle and looming over him menacingly. Again thinking quickly, Woody places his thumb over the open top of the bottle, and shakes the bottle’s contents vigorously. “Have some pop, cop?”. asks Woody, handing the bottle to the officer. The carbonated contents bubble up, and spew out in a torrent, right in the officer’s face. “No stopper, copper!”, quips Woody, giving his laugh, and making a quick getaway before the cop can dry his soaked eyes.

The game commences. The Drips emerge from the dugout – with a new player in the line-up. Woody has somehow managed to join the team, and takes the mound as pitcher. The Drips’ catcher utilizes modern technology to communicate signals to Woody, pushing a button within the side stitching of his mitt, which lights up a neon display upon the glove, reading “Screwball”. Woody goes into a windup – then notices he has forgotten to put on his mitt upon his left hand. Without the pitch being called a balk, Woody removes his hand from the circling ball – which continues circling under its own power – and affixes the glove to his left hand by using his right. Then, without ever affecting the momentum of the ball, Woody inserts his right hand back within the ball’s spiral, matching it in speed to grip it and take control, delivering his pitch. The fancy curve twists the wood of the batter’s bat into a corkscrew. Tossing away the useless implement for a new piece of lumber, the batter shouts to Woody: “Come on! Cut out the fancy stuff. Toss me that ol’ apple!” “Apple?”, inquires Woody, and complies, by replacing the ball with a bright red apple, complete with worm inside. The pitch is made, and the worm utters a scream as the bat is swing – for an instant dose of applesauce. The worm emerges from the shattered fruit, a lump on his head and eye blackened, looking as if muttering remarks which could not be presented without a censor’s intrusion. Woody’s next pitch is not so lucky, as the batter delivers it a powerful sock. Woody invents a play that would be wonderful were baseball organized in Australia. He tosses his glove into the air, in a curve which acts as a boomerang, catching the ball high in the air, then returning the ball to Woody, the mitt landing in a precise fit upon Woody’s wrist.

The game commences. The Drips emerge from the dugout – with a new player in the line-up. Woody has somehow managed to join the team, and takes the mound as pitcher. The Drips’ catcher utilizes modern technology to communicate signals to Woody, pushing a button within the side stitching of his mitt, which lights up a neon display upon the glove, reading “Screwball”. Woody goes into a windup – then notices he has forgotten to put on his mitt upon his left hand. Without the pitch being called a balk, Woody removes his hand from the circling ball – which continues circling under its own power – and affixes the glove to his left hand by using his right. Then, without ever affecting the momentum of the ball, Woody inserts his right hand back within the ball’s spiral, matching it in speed to grip it and take control, delivering his pitch. The fancy curve twists the wood of the batter’s bat into a corkscrew. Tossing away the useless implement for a new piece of lumber, the batter shouts to Woody: “Come on! Cut out the fancy stuff. Toss me that ol’ apple!” “Apple?”, inquires Woody, and complies, by replacing the ball with a bright red apple, complete with worm inside. The pitch is made, and the worm utters a scream as the bat is swing – for an instant dose of applesauce. The worm emerges from the shattered fruit, a lump on his head and eye blackened, looking as if muttering remarks which could not be presented without a censor’s intrusion. Woody’s next pitch is not so lucky, as the batter delivers it a powerful sock. Woody invents a play that would be wonderful were baseball organized in Australia. He tosses his glove into the air, in a curve which acts as a boomerang, catching the ball high in the air, then returning the ball to Woody, the mitt landing in a precise fit upon Woody’s wrist.

Without showing the conclusion of the first half of the inning, we wipe to a shot of an umpire (with hair entirely covering his eyes) announcing change of sides and “Batter up”. Woody must outclass the entire Drips organization, as his instant hiring not only got him the pitcher’s position, but a spot as lead-off batter. (Now, how many teams would have allowed their pitcher to hold anything but ninth position in the batting lineup?) Woody receives one of those old familiar “slow balls” – not even from a wind-up, but by a gentle flick of the pitcher’s thumb and forefinger. Woody swings several times at the ball but misses as it crawls by (though no strike is called by the unseeing ump). The catcher poses with the ball spinning slowly upon one fingertip, smiling in a taunting fashion at Woody. Woody won’t take this lying down – so makes the catcher take it that way, by using the bat to knock the catcher’s feet out from under him. The catcher falls prone on his back, the ball resting upon his protruding lips. Woody stands upon the catcher, and with a call of “Fore”, stomps upon his chest, forcing air from the catcher’s lungs to launch the ball into reach of Woody’s bat. Woody’s sock of the ball virtually duplicates the pinball gag from Popeye’s “The Twisker Pitcher”, bouncing off the heads of seven of the Droops’ infielders and outfielders, then curving back in an arc to conk out the pitcher as well. Woody begins triumphantly rounding the bases, but encounters what could be called runner interference at the plate – in the form of the furious cop, waiting with a new club at the ready. Woody goes into a slide, temporarily disabling the cop by burying him in a mound of dirt. Woody turns to run back to third – but finds the entire revived Droops team, charging him with their bats raised high to pound him. Woody utters a Lou Costello whistle of worry to the audience, then decides how to get out of this pickle. Revving up his tail feathers like a pusher prop, Woody advances in power flight in the direction of the Droops. He charges their bats head-on, relying on his natural wood-pecking skills, to sail right through the line of bats, drilling holes just his size in each one. In the final shot, Woody pops out from a panel in the outfield scoreboard, indicating the Drips as victors 7 to nothing (I thought we were still in the first inning?), and utters his trademark laugh at the Droops. But the fielders get the final say, tossing three baseballs, which become lodged in a row upon Woody’s bill – a symbolic way of saying, “three strikes – you’re out!”

Without showing the conclusion of the first half of the inning, we wipe to a shot of an umpire (with hair entirely covering his eyes) announcing change of sides and “Batter up”. Woody must outclass the entire Drips organization, as his instant hiring not only got him the pitcher’s position, but a spot as lead-off batter. (Now, how many teams would have allowed their pitcher to hold anything but ninth position in the batting lineup?) Woody receives one of those old familiar “slow balls” – not even from a wind-up, but by a gentle flick of the pitcher’s thumb and forefinger. Woody swings several times at the ball but misses as it crawls by (though no strike is called by the unseeing ump). The catcher poses with the ball spinning slowly upon one fingertip, smiling in a taunting fashion at Woody. Woody won’t take this lying down – so makes the catcher take it that way, by using the bat to knock the catcher’s feet out from under him. The catcher falls prone on his back, the ball resting upon his protruding lips. Woody stands upon the catcher, and with a call of “Fore”, stomps upon his chest, forcing air from the catcher’s lungs to launch the ball into reach of Woody’s bat. Woody’s sock of the ball virtually duplicates the pinball gag from Popeye’s “The Twisker Pitcher”, bouncing off the heads of seven of the Droops’ infielders and outfielders, then curving back in an arc to conk out the pitcher as well. Woody begins triumphantly rounding the bases, but encounters what could be called runner interference at the plate – in the form of the furious cop, waiting with a new club at the ready. Woody goes into a slide, temporarily disabling the cop by burying him in a mound of dirt. Woody turns to run back to third – but finds the entire revived Droops team, charging him with their bats raised high to pound him. Woody utters a Lou Costello whistle of worry to the audience, then decides how to get out of this pickle. Revving up his tail feathers like a pusher prop, Woody advances in power flight in the direction of the Droops. He charges their bats head-on, relying on his natural wood-pecking skills, to sail right through the line of bats, drilling holes just his size in each one. In the final shot, Woody pops out from a panel in the outfield scoreboard, indicating the Drips as victors 7 to nothing (I thought we were still in the first inning?), and utters his trademark laugh at the Droops. But the fielders get the final say, tossing three baseballs, which become lodged in a row upon Woody’s bill – a symbolic way of saying, “three strikes – you’re out!”

And then there’s the ever-infamous Tokyo Jokio (Warner, Looney Tunes, 5/15/43 – Norman McCabe, dir.), McCabe’s relentless and ugly send-up of the enemy via an ersatz captured Japanese newsreel. Despite being on opposing sides in a World War, baseball was notably well established even then as a widely-popular sport in Japan, just as in America. Therefore, an opportunity is presented to feature a Japanese sports segment within the film, in the same manner common to American newsreels (though heaven knows if any real newsreels from Japan would have been so structured). We are introduced by a badly-accented announcer (Mel Blanc, of course), who appears to gave his name as similar to Cleveland Indians pitcher Red Torkelson (though I can find no Internet reference to the real Torkelson having any career in sports commentary), to current Japanese “King of Swat”. A ball player stands next to home plate, posing for the camera, with a large trophy visible to one side. But he does not wield a bat. Instead, as a fly (insect, that is) buzzes past him, the athlete pulls out a fly swatter, and starts swinging wildly at the bug. All of his swats miss the target, however, and the insect grabs up the swatter, and uses it to bash down the athlete into a sprawled heap upon the plate. The fly then buzzes over to the trophy, and flies off with it.

And then there’s the ever-infamous Tokyo Jokio (Warner, Looney Tunes, 5/15/43 – Norman McCabe, dir.), McCabe’s relentless and ugly send-up of the enemy via an ersatz captured Japanese newsreel. Despite being on opposing sides in a World War, baseball was notably well established even then as a widely-popular sport in Japan, just as in America. Therefore, an opportunity is presented to feature a Japanese sports segment within the film, in the same manner common to American newsreels (though heaven knows if any real newsreels from Japan would have been so structured). We are introduced by a badly-accented announcer (Mel Blanc, of course), who appears to gave his name as similar to Cleveland Indians pitcher Red Torkelson (though I can find no Internet reference to the real Torkelson having any career in sports commentary), to current Japanese “King of Swat”. A ball player stands next to home plate, posing for the camera, with a large trophy visible to one side. But he does not wield a bat. Instead, as a fly (insect, that is) buzzes past him, the athlete pulls out a fly swatter, and starts swinging wildly at the bug. All of his swats miss the target, however, and the insect grabs up the swatter, and uses it to bash down the athlete into a sprawled heap upon the plate. The fly then buzzes over to the trophy, and flies off with it.

NEXT: Popeye, Bugs Bunny, and Tex Avery all take part in next week’s homestand. See you then.