In Bob Clampett’s first two Looney Tunes — Porky’s Badtime Story and Get Rich Quick Porky — cantankerous Gabby Goat played second banana to Porky Pig. As we’ve seen in Porky’s Party, in its original story sketches, Gabby was slated for another appearance, replaced by an equally temperamental little penguin that better embodied Clampett’s penchant for frantic energy. Clampett openly disliked Gabby as Porky’s sidekick and abandoned any further efforts to pair the two again.

The Schlesinger studio’s latest new character, Daffy Duck, was introduced to moviegoers in the earlier Porky’s Duck Hunt, to which Clampett collaborated with director Tex Avery: his suggestion was to pare down multiple screwy ducks to a “crazy darn-fool” black duck with a white ring around its neck. Most importantly, Clampett’s character animation of the unhinged fowl bouncing away across the lakeshore was a revolutionary breakthrough in animated cartoons.

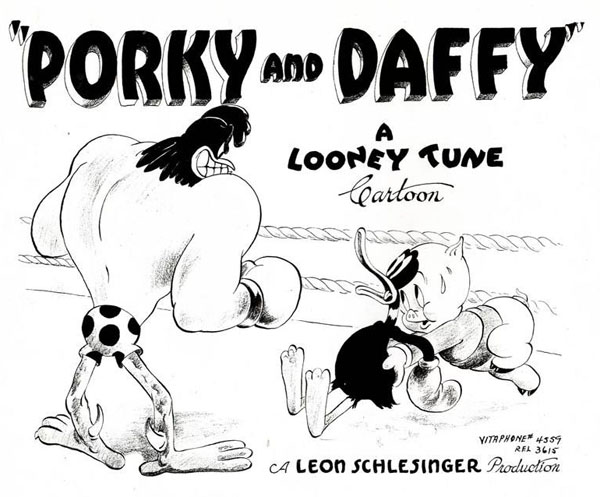

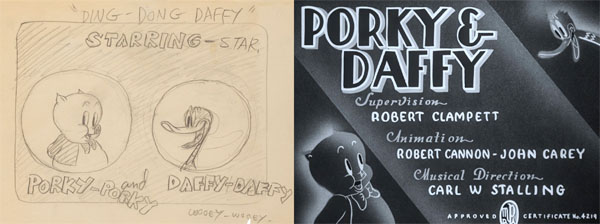

After Avery’s follow-up to Duck Hunt, Daffy Duck & Egghead, the little black duck appeared in Clampett’s What Price Porky; the two characters played discernably different roles (with Daffy billed as General Quacko on-screen) and shared very few scenes. When work finished on Porky’s Party, Clampett conceived a “fight picture” that made the two cartoon stars into a solid double act: straight-man Porky as fight manager and Daffy as his puny boxer. An alternate title, “Ding-Dong Daffy,” was considered during the storyboard phase.

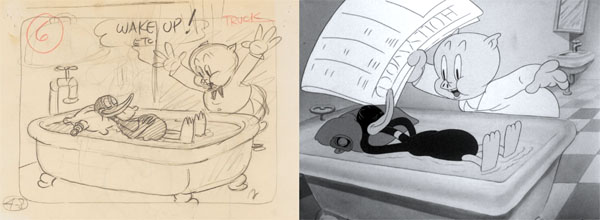

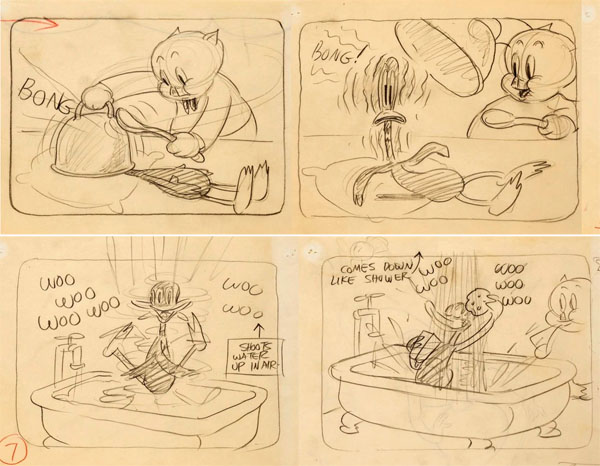

In the film’s opening scenes, animated by Bobe Cannon, Porky spies an advertisement in the morning paper’s sports section: a $500 prize offered to all comers who can last ten rounds with the champ—a gaunt prizefighting rooster—that evening. Recognizing this to be a career match, Porky eagerly sprints upstairs and into the bathroom, where his fighter, Daffy, is asleep atop a water-filled bathtub. Porky tries to shake the inert duck awake, but when that fails, he retrieves a roasting pan lid to cover Daffy’s head and strikes it hard, which rouses the dozy duck into action. For these establishing sequences, Carl Stalling excerpted a recent tune from songwriters M. K. Jerome and Jack Scholl: “Hillbilly from Tenth Avenue,” introduced in Warner Bros.’s musical feature Swing Your Lady.

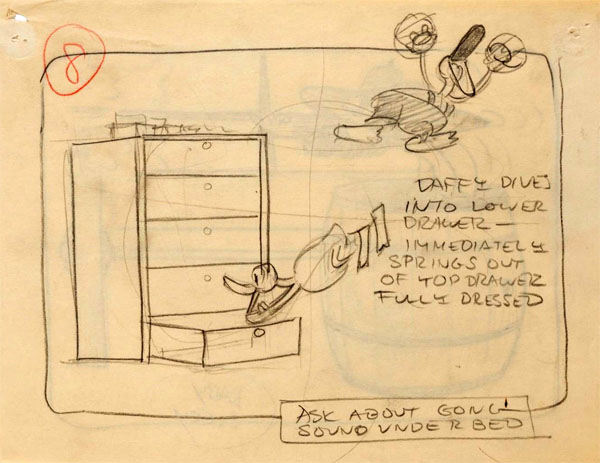

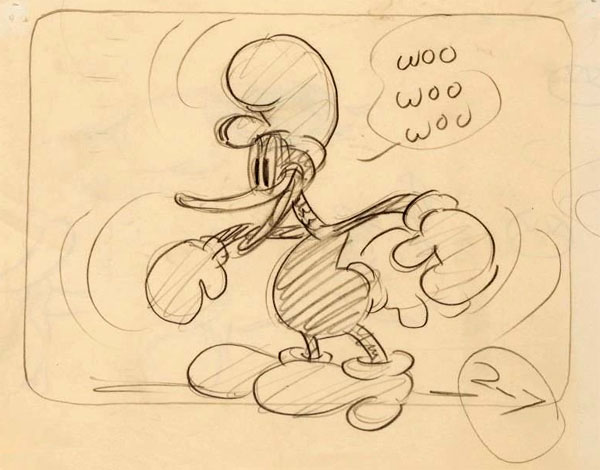

Now full of fight and vigor, Daffy wildly spins around the bathwater, sending it airborne and down again as if emitting from a showerhead. This comic business is suitably accompanied by the strains of “Singin’ in the Bathtub,” in its first usage in a Schlesinger/Warners cartoon soundtrack since 1930’s Sinkin’ in the Bathtub, the first released Looney Tune. The music continues when Daffy makes a nimble dive into the bottom of a dresser, then slides out from the top drawer, now clad in his boxing gloves and trunks.

The viewer then glimpses Daffy’s ersatz training regimen, animated by Chuck Jones. The agile duck hops onto a springy bed, exulting in a series of gleeful scissor-kicks, a movement loosely derived from Stan Laurel—and utilized in Daffy’s screwball antics on the lake in Porky’s Duck Hunt. Daffy practices his boxing techniques on a soft pillow, which ends in an uppercut, launching the cushion off-scene. The exuberant duck whirls and settles into a glorious pose before the pillow falls onto Daffy and wrecks the bedframe in half—an ironic comment on the duck’s grandstanding.

Later that night, the competition approaches, set to the melody of a then-current song from tunesmiths Rube Bloom and Ted Koehler, “Feelin’ High and Happy,” which plays during the ensuing scenes. Inside the arena, a pelican referee stands at the ring center and blows a train whistle for attention in the first of numerous sight gags involving his versatile pouch. The referee asks the jampacked crowd who wishes to volunteer; a gang of brawlers suddenly enter the ring, spoiling for a fight with the pelican. When they realize the champ rooster is their contestant, the toughies quickly scramble away—one voice protests: “Not me—I gotta cold!” Porky accepts the challenge and escorts Daffy’s ostensibly barrel-chested physique to his corner.

Clampett then utilizes a nod to popular radio, spoofing Fibber McGee’s rapid tongue-twisting alliterative speeches: the referee touts the champ as “the most magnificent, marvelous, multiple monstrous, mad mauling mass of meaty muscles ever to master, modify, mat, make mince-meat, and mangle many menacing monsters from Manitoba to Minneapolis!” (To cite one 1937 example from Fibber McGee and Molly: “Honk Honk McGee, I was knowed as in them days…the heady, happy handler of horseless hacks whooping hilariously over high hills and hummocky highways and heartily hated by hundreds of hicks for hitting hens and hogs and haystacks from Hagerstown to Harrisburg!”)

Once a cornerman unzips the champ’s robe, the emaciated rooster becomes a ferocious, musclebound beast. His mighty roar produces a gale that blows off Daffy’s robe, exposing his mock machismo—the duck has flour sacks tucked underneath his arms. Clampett (and animator Chuck Jones) add a touch of Marx Brothers-esque transmogrification: Daffy impersonates a lion tamer, wielding his corner stool and bullwhip to quell the monster back. An advertising jingle, then instantly recognizable to moviegoers, acts as a capper: the pelican’s burbling sounds when Daffy flicks his beak are an evocation of Lee Aubrey “Speed” Riggs’s auctioneer spiel used to shill Lucky Strikes cigarettes. Daffy mocks its slogan: “Sold to the American Tabasco Company!”

The fight begins while the referee warns both contenders (off-camera) not to strike below the belt; Daffy hikes his trunks up to his head! The champ swings with a powerful gust that tears the shorts off Daffy, who flees in terror. Porky shouts for Daffy to use a peculiar strategy: the duck hops on an invisible bicycle and rides it around the canvas. Via exaggerated perspective of the boxing ring, Clampett forces depth into the action during the wide shots of Daffy’s invisible pedaling—as he loops with such speed that it knocks the big rooster flat. Daffy’s few bits of dialogue, which include his comment on this stunt (“I’m so crazy, I don’t know this is impossible!”), provides an early sample of his slurpy duck-like voice with a sibilant, “raspberry” effect that would magnify over time. The hit song “Joseph! Joseph!” functions as a lively chase theme during the sequence, just as it did for Porky and his panicky guests in Porky’s Party.

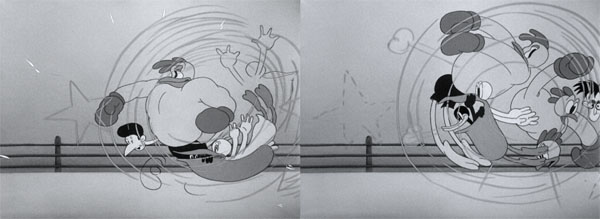

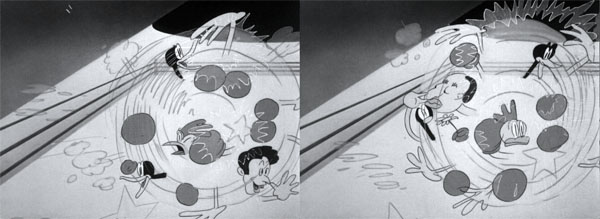

Twice in the cartoon, animator John Carey inserts caricatures of Bob Clampett, other unknown staffers, and an earless Porky in a brawling whirlwind.

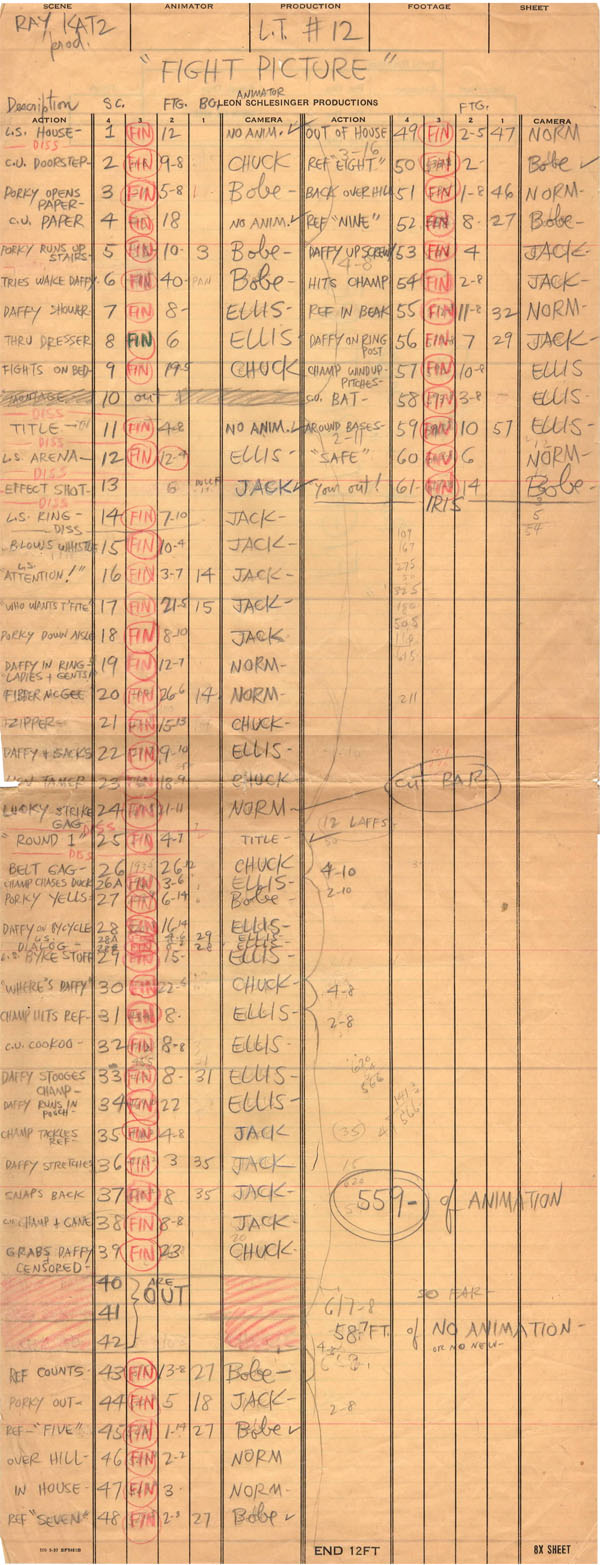

In a brief respite from the absurdity, Daffy vanishes from the fight. As the referee and champ rooster try to locate him, the screwy duck emerges from the pelican’s bill and socks the champ. Still in the referee’s beak, Daffy dodges a haymaker, which the pelican gets in the abdomen—his head bangs against the overhead lamp like a carnival high striker. Daffy pops out like a cuckoo and mashes the champ’s face with his gloves, which sets off a scuffle between the rooster and pelican. Daffy’s teasing doesn’t translate well in the draft: the description for scene 33, “Daffy stooges champ,” alludes to an eye poke from Moe Howard of the Three Stooges. (On the soundtrack, we hear Harry Warren and Johnny Mercer’s “Something Tells Me,” which plays throughout much of the fight.)

The duck again takes cover in the referee’s bill, which stretches like rubber as Daffy scurries around the boxing ring, the pelican in helpless tow. Daffy pauses to quote a limerick (attributed to Dixon Lanier Abernathy): “A funny old bird is a pelican; his beak can hold more than his belican.” When the rooster catches up and pins down the referee’s legs, the pelican’s elastic beak extends farther out and snaps back. In the swirling fracas that follows, Daffy emerges from the referee’s bill unscathed.

Daffy’s clowning is the last straw for the champ; he offers a candy cane to his opponent. Clampett pushes the boundaries of ribald humor when the rooster extracts the present from his boxing trunks and beckons coquettishly to Daffy. The foolish duck falls for it and is beaned on the head. The rooster prepares to pulverize Daffy by pulling down a CENSORED curtain—the sounds of violent thrashing and the malleable animation of the drapery (by Chuck Jones) leave the viewer in suspense. The curtain lifts to reveal that Daffy has only settled down for a nap.

Daffy’s clowning is the last straw for the champ; he offers a candy cane to his opponent. Clampett pushes the boundaries of ribald humor when the rooster extracts the present from his boxing trunks and beckons coquettishly to Daffy. The foolish duck falls for it and is beaned on the head. The rooster prepares to pulverize Daffy by pulling down a CENSORED curtain—the sounds of violent thrashing and the malleable animation of the drapery (by Chuck Jones) leave the viewer in suspense. The curtain lifts to reveal that Daffy has only settled down for a nap.

While the referee calls out the (prolonged) countdown, a frantic Porky tries to revive Daffy. Suddenly, he realizes the solution and bolts out of the stadium. In scene 44, animator John Carey creates a unique anticipation for Porky and has the pig scramble mid-air before exiting. Clampett borrows the rapid cutting techniques pioneered at Schlesinger’s by Frank Tashlin as the shots alternate between Porky rushing back to the house and the referee’s countdown.

The pig arrives just in time with the roasting pan lid from earlier in the film; its noise induces Daffy to get up and fight. The duck does a fast windup and thrusts himself at the champ rooster, which sails him backward and traps the announcer inside his pouch. Clampett’s love of The Three Stooges was an obvious influence based on the contrivance that turns an underdog into an expert fighter. Stooge fans will recognize the similarities in how Curly Howard is affected by Larry’s violin playing “Pop Goes the Weasel” in Punch Drunks (1934) and later, Wild Hyacinth perfume in Grips, Grunts, and Groans (1937).

Fueled by joyful manic energy, Daffy overpowers the champ with wild abandon—the soundtrack reflects his newfound prowess, set to the Johnny Mercer-Richard Whiting song, “Sing, You Son of a Gun.” The screwy duck transports to a corner post, where he avoids several of the rooster’s punches. Daffy then converts the boxing match into a baseball game for the final blow: he draws out a bat and swings at the champ’s fist, which knocks him out, and the duck makes a home run around the perimeter of the boxing ring. For the sake of the gag, the pelican now wears an umpire’s mask—he calls out “safe” and drawls out an expedited countdown to the unconscious rooster. Daffy, now the champ, pops out of the pelican’s beak and strikes the dinner platter over the rooster’s head, which sends him into the same whirling and whooping frenzy as his challenger as the cartoon irises out. (The ending also reveals a story flaw: Porky and Daffy are never awarded the $500 cash prize for their victory.)

When the cartoon was previewed at the studio, Clampett scribbled “12 laffs” on the production papers—a meager amount compared to Porky’s Party’s twenty-eight. Despite the staff’s so-so reception, Porky & Daffy’s closing 35 seconds of the film showcased a major advancement in Clampett’s timing and pacing—such velocity was unprecedented not only in his black-and-white Looney Tunes but also among the other Schlesinger directors.

When the cartoon was previewed at the studio, Clampett scribbled “12 laffs” on the production papers—a meager amount compared to Porky’s Party’s twenty-eight. Despite the staff’s so-so reception, Porky & Daffy’s closing 35 seconds of the film showcased a major advancement in Clampett’s timing and pacing—such velocity was unprecedented not only in his black-and-white Looney Tunes but also among the other Schlesinger directors.

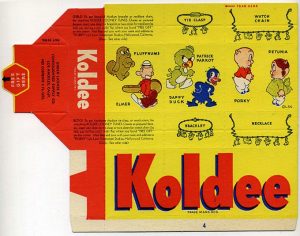

Leon Schlesinger licensed Porky and Daffy in commercial tie-ins around the time of the film’s general release in August 1938: a promotional deal with Koldee Ice Cream featured Porky and his cast of friends. The company sold them as miniature aluminum figures; their wrappers and box clippings contained drawings of Porky, Petunia, Daffy, Fluffnums (Petunia’s obnoxious dog in Tashlin’s Porky’s Romance), Peter Parrot (renamed “Patrick” in merchandising, from Tex’s I Wanna Be a Sailor), and an early version of Elmer Fudd (from Avery’s Little Red Walking Hood and The Isle of Pingo Pongo.)

The Katz unit finished its 1937-38 release season with the first official pairing of Porky and Daffy, which secured the little black duck’s standing as a permanent fixture in Warners cartoons.

Roger Daley, the author of the news story read by Porky, was a staffer in the Katz unit who worked as Bobe Cannon’s assistant. Roger Armstrong, who worked with Daley at Walter Lantz in the forties, recalled in a 1977 audio letter to Michael Barrier: “Roger Daly had been raised by hand by Bobe Cannon…Bobe Cannon had taught him one hell of a lot.” (Roger married Margaret Selby in 1944; she later became known as Selby Daley—or Selby Kelly, third wife of Pogo’s Walt Kelly.)

Thanks to Jerry Beck, Ruth Clampett, Bob Jaques, Frank M. Young, and Daniel Goldmark for contributing to this post.