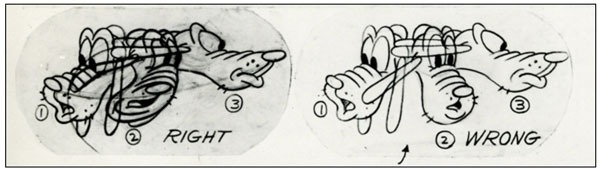

A portion of a 1940s Disney model sheet shows how to deform characters for follow-through in

animation.

It’s hard to imagine that over twenty years ago, the term “animation smear” was not as prevalent as it is today, but it is now widely discussed in animation and in general. Even early research from the 1990s on the short film The Dover Boys at Pimento University did not mention this exact term and was originally praised for its implementation of limited animation, which may have originally referred to the way how the film limits drawings by letting abstracted motion blur accomplish most of the work. The film then grew to be one of the most popular sources of smears despite not originally being touted as such. For how popular the short is, it leaves us some questions: do we even know for sure who created the term or how it became prevalent in history? If there is such documentation, does it still exist today?

It is plain to see that the terminology for animation has evolved, with some terms being different across different parts of the world. “Animation smear” basically describes the technique of artistically implementing motion blur into animation. This generalized term has become so mainstream that it offers the animator more control of the visuals than ever before. Back then however, in an era where everything was done with traditional tools, the artists were required to have significant knowledge and skill of their profession to communicate every detail and instruction to the animation staff involved. Along with these instructions would have been guides, names, or terminology to address parts of the drawing that required the animator to abstract movement to ensure that others, such as the ink & paint artists, replicated them. Surprisingly, many of these terms still exist today or have been preserved in another way. This focus is on early animation smear terminology that were either named by artists or named after specific processes in animation, all of which usually describe the visual appearance of the smear technique or the unique application of it.

The term “Smears” itself seems to have become popular in the 2000s. In his instructional animation book, Character Animation Crash Course, published in 2008, Eric Goldberg coined this term for the technique. This name helped generalize all types of smears into one category, as they all similarly used creative adaptations of motion blur into animation. However, the specific implementation of stretching the character model for motion was defined as two categories by Goldberg: Long Smears for larger areas of distance that would warp the character significantly and Mini Smears for shorter distances that would look almost identically to standard squash & stretch depending on the action. An even earlier name for this type of smear was called the Elongated Inbetween by animator Ken Harris, first reported in 2001 by Richard Williams in The Animator’s Survival Guide. Technically, all of these names are correct as to how an artist would accomplish this specific deformation in film, as it requires a special inbetween that deformed movements into more prominent and abstract shapes. Ken Harris’s naming of the technique highlights an interesting connection to “The Dover Boys,” as it too featured stretched inbetweens, but this technique was used before the creation of that short in earlier films that also credit Harris by name. This was before Chuck Jones was credited for applying smears in “Dover Boys” later in history. If Jones was responsible for the techniques used in that film, they were likely to be known as the earlier name of elongated inbetween as that is more accurate to the majority of techniques depicted. Even so, “Dover Boys” features other instances of animated motion blur that aren’t elongated shapes but this is to a limited degree.

The term “Smears” itself seems to have become popular in the 2000s. In his instructional animation book, Character Animation Crash Course, published in 2008, Eric Goldberg coined this term for the technique. This name helped generalize all types of smears into one category, as they all similarly used creative adaptations of motion blur into animation. However, the specific implementation of stretching the character model for motion was defined as two categories by Goldberg: Long Smears for larger areas of distance that would warp the character significantly and Mini Smears for shorter distances that would look almost identically to standard squash & stretch depending on the action. An even earlier name for this type of smear was called the Elongated Inbetween by animator Ken Harris, first reported in 2001 by Richard Williams in The Animator’s Survival Guide. Technically, all of these names are correct as to how an artist would accomplish this specific deformation in film, as it requires a special inbetween that deformed movements into more prominent and abstract shapes. Ken Harris’s naming of the technique highlights an interesting connection to “The Dover Boys,” as it too featured stretched inbetweens, but this technique was used before the creation of that short in earlier films that also credit Harris by name. This was before Chuck Jones was credited for applying smears in “Dover Boys” later in history. If Jones was responsible for the techniques used in that film, they were likely to be known as the earlier name of elongated inbetween as that is more accurate to the majority of techniques depicted. Even so, “Dover Boys” features other instances of animated motion blur that aren’t elongated shapes but this is to a limited degree.

Another common type of smear is the Multiple, which is a technique used in animation that is likely related to the art of multiple exposures in photography. Paintings of people with multiple limbs are a popular subject in art history and evolved from the works of artists made decades before film animation. The abstract nature of multiples eventually found its way into early photograph studies, suggesting that multiple frames of an action can be tied to a single movement. Comic artists likely saw the appeal of these early photographs and studies featuring multiples, to which they eventually applied them into their own work before it gained more prominent usage as a viable technique in animation. One example of multiples is combining different frames together that were captured at varying exposures, creating the illusion of ghosting or abstract imagery to simulate an effect similar to motion blur. Animators sought to ease the process by creating multiples of the action within the same drawing and frame, avoiding a complicated procedure in film by ironically making the action more readable on a single layer of animation rather than several. This is a similar feature and common theme between most techniques that adapt motion blur into animation: the deformation is rendered inside a single character cel. Whoever first adapted the name for multiples in animation is unknown, as it is likely an application that came from the previous generations of art. Much like the term “smears,” the name of the technique began to get more widely known in the late 2000s.

Another common type of smear is the Multiple, which is a technique used in animation that is likely related to the art of multiple exposures in photography. Paintings of people with multiple limbs are a popular subject in art history and evolved from the works of artists made decades before film animation. The abstract nature of multiples eventually found its way into early photograph studies, suggesting that multiple frames of an action can be tied to a single movement. Comic artists likely saw the appeal of these early photographs and studies featuring multiples, to which they eventually applied them into their own work before it gained more prominent usage as a viable technique in animation. One example of multiples is combining different frames together that were captured at varying exposures, creating the illusion of ghosting or abstract imagery to simulate an effect similar to motion blur. Animators sought to ease the process by creating multiples of the action within the same drawing and frame, avoiding a complicated procedure in film by ironically making the action more readable on a single layer of animation rather than several. This is a similar feature and common theme between most techniques that adapt motion blur into animation: the deformation is rendered inside a single character cel. Whoever first adapted the name for multiples in animation is unknown, as it is likely an application that came from the previous generations of art. Much like the term “smears,” the name of the technique began to get more widely known in the late 2000s.

An early derivative of the multiples technique called the Flurry Effect was primarily used for repeated actions, and similar instances of this type of smear are still present today. It was initially named by Fleischer animator Dave Tendlar and brought to recognition as early as 2007 by historian Greg Ford for the audio commentary of the short film Choose Your ‘Weppins’. It was the Tendlar’s most significant contribution to the animation in the early Popeye cartoons by depicting characters with a sudden burst of activity and quickly shifting to looping actions that make use of multiples of the action they are performing, before eventually reverting back into full undeformed animation. The technique initially appeared in Tendlar’s earliest directed films in the early 30s for sequences that usually involve sword fights and quick movements of hands or feet. However, the flurry effect had been previously present in the studio’s past catalog for years and was mainly used for fight sequences that featured multiple limbs inside of cartoon dust clouds.

An early derivative of the multiples technique called the Flurry Effect was primarily used for repeated actions, and similar instances of this type of smear are still present today. It was initially named by Fleischer animator Dave Tendlar and brought to recognition as early as 2007 by historian Greg Ford for the audio commentary of the short film Choose Your ‘Weppins’. It was the Tendlar’s most significant contribution to the animation in the early Popeye cartoons by depicting characters with a sudden burst of activity and quickly shifting to looping actions that make use of multiples of the action they are performing, before eventually reverting back into full undeformed animation. The technique initially appeared in Tendlar’s earliest directed films in the early 30s for sequences that usually involve sword fights and quick movements of hands or feet. However, the flurry effect had been previously present in the studio’s past catalog for years and was mainly used for fight sequences that featured multiple limbs inside of cartoon dust clouds.

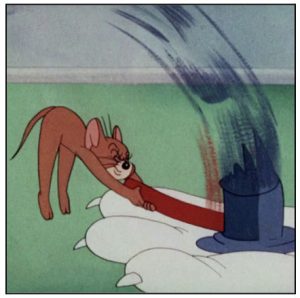

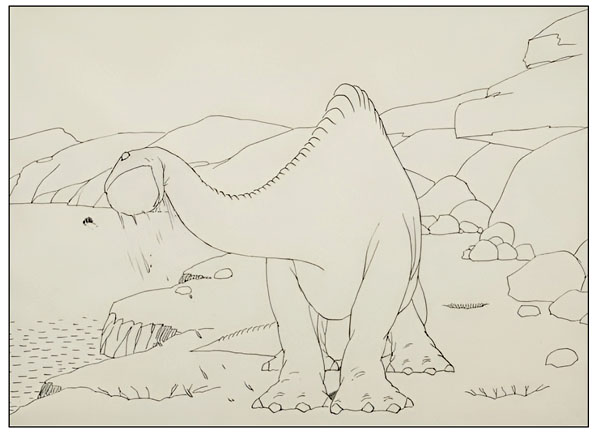

Another technique that was originally intended for all types of various scenarios was called Trails, which is a type of smear with a somewhat obscure history. While the name and its original creator are unknown, the term has at least been used as early as 2009 in a blog post made by animator Mike Ruocco. Despite the relatively recent naming, this technique is actually present in some of the earliest animated films, with a prototype of the technique appearing as early as 1914 in Gertie the Dinosaur when the character throws a rock. The method involves deforming the outer areas of an object in motion with triangular shapes that abstract the form due to fast-occurring motion blur. Early animation commonly featured speed lines drawn onto the cels that mimicked a different form of motion blur that did not directly deform the character. Later on, animators began to purposefully combine these usually sharp lines directly into the characters themselves and sometimes would even round off the appearance of these triangle-shaped deformations to make them seem more like natural movement. The jagged looking nature of trails makes it more usable in situations where actions depend on the character’s strength rather than applying more simplistic smear drawings like the elongated technique mentioned previously. The term and drawing style of this specific type of smear has been more popularized due to their appearance in more recent action-oriented animation such as anime, making it rarely appear as a standard type of smear in cartoons today.

Another technique that was originally intended for all types of various scenarios was called Trails, which is a type of smear with a somewhat obscure history. While the name and its original creator are unknown, the term has at least been used as early as 2009 in a blog post made by animator Mike Ruocco. Despite the relatively recent naming, this technique is actually present in some of the earliest animated films, with a prototype of the technique appearing as early as 1914 in Gertie the Dinosaur when the character throws a rock. The method involves deforming the outer areas of an object in motion with triangular shapes that abstract the form due to fast-occurring motion blur. Early animation commonly featured speed lines drawn onto the cels that mimicked a different form of motion blur that did not directly deform the character. Later on, animators began to purposefully combine these usually sharp lines directly into the characters themselves and sometimes would even round off the appearance of these triangle-shaped deformations to make them seem more like natural movement. The jagged looking nature of trails makes it more usable in situations where actions depend on the character’s strength rather than applying more simplistic smear drawings like the elongated technique mentioned previously. The term and drawing style of this specific type of smear has been more popularized due to their appearance in more recent action-oriented animation such as anime, making it rarely appear as a standard type of smear in cartoons today.

An original drawing from “Gertie the Dinosaur” showcasing an early version of the trails smear. The smears dissipate from the figure and become water droplet-shaped, a recurring animation effect seen in early cartoons from the 1920s and 1930s to indicate motion blur.

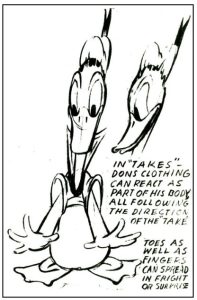

As animation became more experimental, the founding animation principles logically evolved into a different variant of a smear type. For example, a common way for animated characters to react is through an animated Take, which refers to the visible motion of a character reacting to a situation. One of the earliest usages of the term appears in model sheets from the late 1930s, but the name has appeared as early as 1935 on storyboards, so a clear origin or creator cannot be determined. Early uses of the animated take barely had the characters responding or were limited by their scenario, so animators later developed ways to keep the animation visually interesting by using squash and stretch to indicate these reactions. Later, these principles evolved into more extreme examples that vividly deformed the characters within one frame of animation, often used by Disney artists like Woolie Reitherman, Don Patterson, and most famously by Hugh Fraser, whose usage of this variation became a personal trait. This smear version of the take uses an area of the character, such as the head or eyes, and then greatly enlarges the shape to imply a quick and abrupt reaction. It works best when executed in the opposite direction of the character’s current action before returning to its original form. This method gradually faded out as newer techniques emerged, allowing animators to creatively depict animated takes in more ways instead of one.

As animation became more experimental, the founding animation principles logically evolved into a different variant of a smear type. For example, a common way for animated characters to react is through an animated Take, which refers to the visible motion of a character reacting to a situation. One of the earliest usages of the term appears in model sheets from the late 1930s, but the name has appeared as early as 1935 on storyboards, so a clear origin or creator cannot be determined. Early uses of the animated take barely had the characters responding or were limited by their scenario, so animators later developed ways to keep the animation visually interesting by using squash and stretch to indicate these reactions. Later, these principles evolved into more extreme examples that vividly deformed the characters within one frame of animation, often used by Disney artists like Woolie Reitherman, Don Patterson, and most famously by Hugh Fraser, whose usage of this variation became a personal trait. This smear version of the take uses an area of the character, such as the head or eyes, and then greatly enlarges the shape to imply a quick and abrupt reaction. It works best when executed in the opposite direction of the character’s current action before returning to its original form. This method gradually faded out as newer techniques emerged, allowing animators to creatively depict animated takes in more ways instead of one.

As shown, animation smear techniques are a complex subject with many variations, sometimes blending other principles of animation and techniques into one. Some of these examples can also use Drybrush, which is a different application of motion blur that normally does not directly deform the character cel, that can be combined with smears to help depict the blur more closely to the artist’s original vision. However, many techniques lack official names or creators due to varying terminology and usage. To promote a more universal understanding of these animation smear techniques, my recent publication of The Animation Smears Book: Uncovering Film’s Most Elusive Technique aims to shed light on this subject by becoming the first textbook solely dedicated to the art of abstract motion blur. The book includes more examples of techniques named by artists, highlighting the importance of recognizing and preserving the work of those who created actual new forms of movement while they were simply applying artistry to their drawings. The obscure nature of smears results from a continued lack of archived documentation for these efforts, and it is crucial to uncover these techniques before their history is lost forever.

Special Thanks goes to Esther Bley, Strummer Cash Petersen and Devon Baxter for their contributions and improvements to the writing of this article.