“A radio writer in a year’s time turns out a great number of programs—some of them good, some of them bad. But good or bad, they all as dead after their allotted minutes on the air. Radio is the only medium of entertainment in which the premiere is also the final performance. Once in a fortunate moon, however, an idea comes out of nowhere—the plot falls into line—the words form themselves on the page—and something is brought about that people hear and ask to hear again. That was the case of The Littlest Angel…”

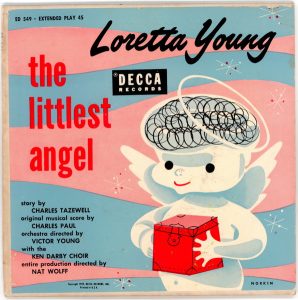

-Author Charles Tazewell, from the Decca Littlest Angel record album notes

It’s the ultimate fish-out-of-water story. A young boy finds himself in Heaven for no apparent purpose but to become a nuisance and a failure. He asks his guardian angel to grant one wish: a brief return to earth to retrieve his greatest possession, a small, ordinary-looking box.

The Littlest Angel originated in the golden age of radio drama and comedy. Sometime during the late ’30s or the early ’40s, a young scriptwriter named Charles Tazewell was pitching it to the networks of the era. As Tazewell himself wrote, The Littlest Angel “was the child prodigy that was born on a Christmas episode several years ago—Manhattan at Midnight to be exact—a very strange place for him to appear—but he crawled into ears attuned to crime, adventure and gunplay and woke up the very next morning to find himself a part of Christmas.”

The Littlest Angel originated in the golden age of radio drama and comedy. Sometime during the late ’30s or the early ’40s, a young scriptwriter named Charles Tazewell was pitching it to the networks of the era. As Tazewell himself wrote, The Littlest Angel “was the child prodigy that was born on a Christmas episode several years ago—Manhattan at Midnight to be exact—a very strange place for him to appear—but he crawled into ears attuned to crime, adventure and gunplay and woke up the very next morning to find himself a part of Christmas.”

The melodramatic half-hour Manhattan at Midnight anthology program aired on the “Blue Network” from July 24, 1940, through September 1, 1943. Without access to the precise Christmas episode, based on Tazewell’s statement, The Littlest Angel would have premiered between 1940 and 1942, though it could have been written earlier.

According to the biography of Hollywood star Loretta Young (The Bishop’s Wife, Cause for Alarm, The Farmer’s Daughter) by Joan Wester Anderson, recounts a night in 1944 when Tazewell was at a broadcast session for Armed Forces Radio, a network founded by Young’s husband, producer Tom Lewis, to produce shows, especially for overseas WWII soldiers. Actor Spencer Tracy had just finished performing a radio version of another Tazewell Christmas story, The Small One (which was made into a 1978 Disney animated featurette directed by Don Bluth) After the show, Tazewell, now a renowned scribe, greeted Lewis and Young.

“Someday I’ll write something for you,” he said to her.

Loretta Young (right) with Cary Grant and David Niven in the classic The Bishjop’s Wife.

The following year, a package containing the script for The Littlest Angel arrived at the home of the Oscar-winning star with this note: “Dear Loretta, this is for you. Do anything you want with it. Love, Taze.”

Young loved the script and immediately called her agent. He arranged for Decca Records to record it and sent the script to the president of the label. Later that week, at a meeting with the Decca Records president, another Oscar-winning superstar, Greer Garson, spotted the script on his desk, fell in love with it and wanted to record it. Neither she nor the Decca exec knew about Tazewell’s note to Young.

Young was sure Garson would do a fine job (decades later, she graced two Rankin/Bass classics, The Little Drummer Boy and Little Drummer Boy; Book II. But Young earnestly wanted to record it herself—but couldn’t find Tazewell’s note proving his intent. Plus, it was Friday and Young was committed to a retreat over the weekend. Thinking ahead, Young’s agent had already booked a Saturday recording session in Hollywood anyway.

To fully appreciate what happened next, it is important to know that there were no recording isolation booths or sound mixers in recording booths of that day. They rarely if ever separated vocals, music, and dialogue for records. A musical story album like The Littlest Angel would be recorded with the narrator, orchestra, and chorus all together in the studio, at the same time as if it were a live performance. For an 18-minute story, it required six sides of three 78-rpm discs—a total of six three-minute segments. (The three discs were slipped into three brown envelopes bound in a book-like hardcover package very much like a photo album, hence the name “record album.”)

On Saturday at 6 p.m., Young drove from the retreat to the recording studio. Once she ran through just one reading with the orchestra, according to biographer Anderson, she “suddenly realized that this project was graced. The practice had been completely flawless, and there seemed to be no need for another. Instead, the director decided they would try an actual recording. Musicians looked at each other. How could anyone be ready for a take?

“But no one made the slightest mistake this time either—no stumble or missed dialogue from Loretta, nothing dropped or banged, no technical problems, not even a sour note on a violin. When it was over, everyone sat in disbelieving silence. Such a thing had never before happened. ‘I-I think that’s a wrap,’ he announced in wonder.”

Six sides with a full orchestra and chorus with no mistakes. Ms. Young returned to her retreat at 10:30 the same night. The resulting 1945 record album was a best seller for generations on 78, 45, and LP records. If you would like to hear what it sounds like when Loretta Young makes a slight mistake, search out the live December 21, 1949 episode of the radio show Family Theater, in which she does an encore of The Littlest Angel with the entire orchestra and chorus.

Tazewell adapted The Littlest Angel into a book in 1946 and it has never been out of print in one form or another ever since.

In 1950, a modest animated version of The Littlest Angel was produced by Coronet Films, a familiar name to school age baby boomers when their teachers rolled out the old Bell and Howell 16-millimeter projector to show educational movies providing scratchy, bleary relief from regular lessons.

According to our esteemed colleague, animator/film archivist Steve Stanchfield in this Cartoon Research article. The cartoon was produced by Hugh Harman Productions for Coronet. Harman, along with Rudolf Ising, was a key creative player in the early days of the Walt Disney Studios and also created classic cartoons for MGM. By this time however, the glory days and the big budgets were in the past. Nevertheless, the art direction on this Angel is charming despite the limited movement, which is accomplished primarily through dissolves. Two educated guesses are that the narrator is Norman Rose (Pinocchio in Outer Space, Dimension X) and the character design suggests Peter Pan Records Disney merchandise artist George Peed.

“In 1990 or so, I talked with animator Gordon Sheehan, who remembered working on this film in 1949 or 50, in house at Coronet,” wrote Stanchfield in Cartoon Research’s Thunderbean Thursday feature. “He remembered it being in production for many months, and long hours trying to get it finished. Hugh Harman was directing from California, sending layout drawings and some limited animation on the main characters to Coronet in Chicago. It appears that all the backgrounds were painted at Coronet.”

It wasn’t until 1997 that another animated Angel came along. It looks as if it might have been conceived as a TV special or even a series before it became a direct-to-video release. Running just under 30 minutes, it features stage and animation actor Tabitha St. Germain, veteran of hundreds of cartoons, but best known to My Little Pony viewers as the voice of Rarity.

A sequel called The Littlest Angel’s Easter was released the following year. The premise was nowhere near as lofty as the original—in this story, he helps a lonely young boy keep his dog. Perhaps this was intended to become a series of videos, sort of a children’s version of Highway to Heaven or Touched By An Angel.

The story was expanded to feature film length in 2011 for another direct-to-video release, this time rendered in CG animation, directed by Hollywood special effects producer Dave Kim. The aforementioned Steve Stanchfield was a key animator and storyboard artist on this film.

Steve wrote: “The boards were fun to do, and had to be done fast–I tried to add as many gags as I thought I could get away with. I boarded about 25% of that feature; in the end I was given an animation director credit on the film, something I didn’t do–but I think they gave the credit because I did so many poses in my boards to try to get some personality in a fairly straightforward script. The whole time working on it I thought about this little film and the fun personality and ideas in the poses.”

To date, no adaptation of The Littlest Angel has been more lavish and successful than the 1969 Hallmark Hall of Fame TV version of The Littlest Angel. The project originated with three-time Emmy-winning writer/composer Lan O’Kun, who worked with such stars as Barbra Streisand, Frank Sinatra, and for 44 years with iconic ventriloquist Shari Lewis. O’Kun wrote over 1,300 television shows, including the longest-running children’s show in the world, Tales of the River Bank in England, which ran in 89 countries in 50 languages. Among his current projects is a collection of poems about animals.

“The Littlest Angel television musical came about because a producer named Lester Osterman had a daughter, Patricia Gray, who came across the book and wanted to do the show,” composer/lyricist/coscreenwriter O’Kun told me. “Working for Mr. Osterman was Larry Kasha who was a television producer [Knots Landing] and a friend of mine. He said “It occurs to me that you’re so involved in the children’s area, that you might be interested.”

A few names began to form for roles in the musical. “When I was thinking of somebody to play Gabriel, the first name that came into my mind was Cab Calloway,” said O’Kun. “He had been famous since the early ’30s, when I was born. I called him up and asked him if he would be in the show. He said, ‘Come on over!’

“He happened to be living in White Plains, which was near where I was living in Scarsdale. I went to his house and played “Heavenly Ever After” for him and he said, ‘Oh, I’ll do that!’ He did a demonstration record of it for nothing–if you can believe–for nothing. We went to Hallmark in Chicago, played it for them and they said, ‘Winner!’ That became The Littlest Angel because Cab Calloway was so famous. It was Cab Calloway who really sold The Littlest Angel for me. When we went to the recording studio and he sang it, he was wonderful. I applauded and said, ‘Wonderful! Wonderful!’ And he said, ‘Okay, now off to Belmont!’ What a wonderful guy.”

Actress Anissa Jones and Johnny Whitaker during filming of the television show ‘Family Affair,’ 1967. (Photo by Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images)

Nine-year-old Johnny Whitaker was appearing in Family Affair’s fourth season when he was cast as little Michael. “I had heard of the story,” he said. “Interestingly enough I think that [Family Affair star] Brian Keith was supposed to read the story or something, I can’t remember exactly. But my agent said they were looking for a young star and my agent submitted me. I don’t remember having done any audition at all, necessarily. They asked if I could sing, we said of course, I’m not exactly operatic. My voice does not belong with the Vienna boys choir!”

The special was created in three phases. First, the cast and members of the production staff rehearsed for roughly a month at a Broadway theater. Whitaker recalls the theater was the same one where Peter Pan with Mary Martin was produced in 1954, because flying equipment was necessary (that would make it the Winter Garden Theater). The second phase was three days of taping at NBC studios in Brooklyn. Phase three was an additional film shoot in Santa Clarita, California at Vasquez rocks in Agua Dulce, for the opening title sequence in which Michael chases the dove.

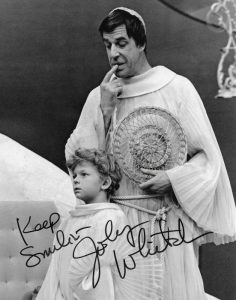

Johnny Whittaker with Fred Gwynne

Fred Gwynne will always be a pop culture immortal on TV’s The Munsters, as well as a consummate actor of stage and screen. He is cast to perfection as Patience in The Littlest Angel, a grownup mentor to Michael who retains a bit of his childlike side. The same warm, approachable likeability that Gwynne gave to Herman Munster and Officer Francis Muldoon on Car 54, Where Are You? brings the same charm to Patience.

“He was a gentle giant,” smiles Whitaker. “Really nice. I had known him because Butch Patrick was my friend. We had a great time. During rehearsals, he would work on the lines with me, give me hints on how to memorize, how to think of things, word associations. Since I was on Family Affair at the time, Patience was kind of an Uncle Bill character, but a little more childish than Uncle Bill. We did things in rehearsal that were a little crazy, some stupid stuff. You could see that relationship on the screen.”

“Fred Gwynne had not sung solo professionally,” recalled O’Kun. “And he took good care of Johnny Whitaker. They became good friends when they were on stage together. He sang a song called “What Do You Do When You Say You’re Doing Nothing?”, which I had originally written for Shari Lewis. Fred said to me, ‘How are we going to do this? I need to watch you conduct.’ ‘I’m not a conductor,’ I said. So, when he was in the studio in front of the microphone, I conducted him from behind the glass door of the studio and that’s how he first did the song.”

Some of the songs and/or music heard in The Littlest Angel were prerecorded in New York, some were sung on camera, and some were added afterward. Depending on the scene, a viewer might see performers singing on camera or lip-synching to a track. The original cast album on Mercury Records was a combination of the prerecorded New York tracks; soundtrack material from the final videotape; special narration and dialogue by Fred Gwynne, Johnny Whitaker, and Cab Calloway; and choral sections within some songs either in place or alongside Johnny Whitaker’s vocals. The album alternates between stereo or mono. Perhaps because of the complexity of its production, the entire flying sequence with Whitaker and Connie Stevens is completely drawn from the mono video track.

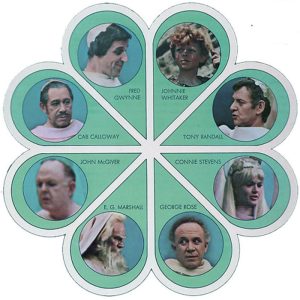

The Cast of “The Littlest Angel” – Click to enlarge.

“Connie was pregnant with Joely Fisher at the time,” Whitaker remembered. “She had to be harnessed on the flying device and swung around. She was constantly throwing up off camera. Right into a bucket.”

Lan O’Kun was on the set to help her. “When she came flying down to the ground and was gonna barf, I grabbed around the head and her chest–as my father had taught me–and held her while she threw up. When she was finished throwing up, she went right back up and did it again. What a trouper.”

“I didn’t fly that much, but uhhhh…” Whitaker groaned. “I was exhausted. So, they finally said, ‘We have one more take and we can go home.’ With her green face, Connie looked over toward me and said, ‘If Johnny can do it, I can do it.’ And I looked over to Connie and said, ‘If Connie can do it, I can do it.’ We went up, got a take and we were done for the day.”

For a nine-year-old boy, throwing up wasn’t as bad as missing out on ice cream. For 30 days before they taped the flying sequence, Whitaker could not eat any ice cream because of the phlegm it would produce. When the filming ended in the middle of the night, there was a mad search for ice cream through New York until someone found an all-night Chinese restaurant. “I got orange sherbet,” Whitaker said, with a nine-year-old’s shrug. “It wasn’t ice cream.”

The special effects in The Littlest Angel quickly look quaint and primitive today. The rapid advances in technology spread to local and network broadcasts. Whitaker would experience it used again in Sigmund and the Sea Monsters—one of Sid and Marty Krofft’s most successful series. Of course, anyone can create this “miracle” today on phones and laptops.

Like any form of special effects in media history, it isn’t the limitations of an era or budgets that made them work, it was ingenuity and execution. The creative team made the most of the color, smoke, and light effects in The Littlest Angel, creating its with just 72 hours of studio time.

Whitaker recalled the basic way the general cloudy look was created. “One camera was always pointed at a device that looked like a cigarette. It slowly burned, and the smoke went into a box that they filmed into.

“My tunic couldn’t have any blue in it. My eyes were the only things they worried about. They were going to give me contact lenses to change the color of my eyes, so they put me on the blue screen to test that I didn’t look blind, or that no objects could be seen moving in the back of my eyes, but it worked out okay.”

Tony Randall was one year away from five seasons as Felix Unger on ABC’s The Odd Couple, and the role of the angel Democritus was not unlike the lovable fussbudget. O’Kun wrote “You’re Not Real” to fit his comic persona, a self-assured philosopher who believes he has dreamed up everything he sees. Singing with him are Lu Leonard and Mary Jo Catlett as heavenly clerks (Spongebob fans know Catlett as the voice of Mrs. Puff). On the record album, a singular female vocal is handled by New York session singer Corinna Manetta, a former schoolmate of Lan O’Kun.

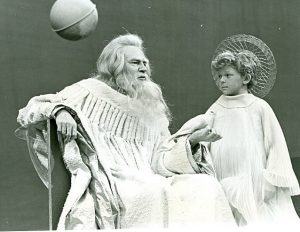

E.G. Marshall as “God” with Johnny Whittaker, in “The Littles Angel”

E.G. Marshall accepted the role. Whitaker didn’t recall much discussion with the venerable actor. “I think he wanted me to be more in awe of him so we did not really have much of an interaction.”

The Saturday evening of December 6, 1969 (55 years ago in 2024) when Hallmark presented The Littlest Angel on NBC, those “in the know” were betting on CBS to blow it out of the water with a glittering Ann-Margret variety special. When the TV ratings came in, Lan O’Kun got a phone call from the producer at CBS. “He said, ‘I put on that show and my son insisted on seeing The Littlest Angel and I said ‘No, we’re watching this,’ and he said, ‘No were not, we’re watching Littlest Angel.’ I knew what a failure we were! We had a 15 rating and you had guys had a 43 or something!’”

Perhaps CBS underestimated the drawing power of one of their own stars, Johnny Whitaker, as well as one of their former stars, Fred Gwynne, seen in constant reruns on The Munsters (the impact of syndication on pop culture was only just beginning to be understood). It was also a Christmas special with a powerful message—a message that can be trite if not presented correctly, but when done well, can stand up to the pressure, confusion, commercialization, and complexity of the holiday season. There is no denying that the chroma-key effects of 1969 were primitive and seem quaint now, but somehow the beloved films and shows of the holiday season transcend the limitations of their era.

Whitaker sat down with me at the Walt Disney Studios, where he had filmed Napoleon and Samantha with Jodie Foster and Michael Douglas, as well as The Biscuit Eater, Snowball Express, and The Mystery in Dracula’s Castle, to remember being Michael The Littlest Angel. He had decades to reflect on the story’s messages and the special and was glad to share them.

“For whatever reason, God had another choice for Michael. Michael needed to go back to Heaven therefore he sent this dove that he follows… then the dove is on this old man’s shoulder–E.G. Marshall, who turns out to be God at the end. The whole purpose of that is, in my opinion, he came to Heaven to teach the angels about the things that are the most important in life. They’re too busy doing what ‘they are supposed to be doing.’

“God brings in this little angel who‘s a little (chuckle) s**t and a little annoying, and not supposed to be there. Yet there he is, to present this simple box. All their gifts are beautiful, but the ones that come from the heart, are the little things that boy had in his box. the precious things that he went back to earth to get. The most important things on earth to him, he gave up to the Christ child.”

In addition to continuing to act, directing and make personal appearances, Johnny Whitaker adds that, “For the over two decades, I’ve been a drug and alcohol counselor, helping people in that way. Among his recent credits is the television series Idol Chat, and The Last Evangelist, as well as the satirical show, Therapy TV.

Johnny still gets lots of comments about The Littlest Angel from fans—and one in particular. “My nephew. He’s now almost 50 and it’s still his favorite.”

“To all those people who have been kind enough to ask to meet him again — I and The Littlest Angel thank you—and hope that you, and all of you—have the merriest Christmas always.”

– Charles Tazewell, from the Decca record album notes

Upon hearing Fred Gwynne’s excellent narration of this stereo Mercury TV cast album, it makes one wish he had done more recordings. Cab Calloway provides additional narration. You’ll also hear Tony Randall basically as Felix Unger in Heaven and Connie Stevens trying her best to keep flying.