All our action this week is centered upon four characters, all installments containing self-winks to the illustrated media. Tex Avery contributes another dose of Screwy Squirrel. Four appearances by Bugs Bunny – two in unlikely settings. And an extended discussion on various installments of Popeye. Plus, some pointed references to the Son of Krypton – without any actual appearances by the hero himself.

First, with apologies, some shorts overlooked as to chronological order. Though not in itself recognizing the characters of the film as animated creations, George Pal’s A Hatful of Dreams (Paramount, Madcap Models, George Pal, dir.) makes a name-dropping reference to the animation/comics history of another series previously in production by Paramount studios – though the series had already officially ended with the substitution of the Noveltoons. The film thus receives an honorable mention. (NOTE: online data on this film is sketchy and incorrect in many particulars, including major differences in alleged release date. IMDB (with very little other data) claims release on an unspecified date in January, 1944. Graham Webb lists a release date for this film in his book as April 28th, 1945. Big Cartoon Data Base (which completely misattributes voice roles) states its release date as July 6th, 1945. Anyone with a more reliable source of data is invited to contribute.)

A star-crossed would-be romance forms the basis for this story, between Judy, an attractive little thing, shapely and with the added effect of some highly-realistic heavy breathing, and Punchy, a kid of the streets with patches on his pants, in a tenement-laden urban tough neighborhood. He’s not the only one with eyes for Judy, who moons for romance on an upper-story fire escape. The toughest kid on the block tries to impress with muscles. The rich kid from across the tracks (although he dresses like Little Lord Fauntleroy), comes equipped with an entourage of servants bearing expensive trinkets and candies for Judy. A street-wise narrator observes that Punchy can only offer “nothin’ but nothin’”. Stoop-shouldered and dejected, Punchy can only feel small – and smaller – and smaller, shrinking to the size of a tossed-away cigar butt as he mopes his way down the street.

A star-crossed would-be romance forms the basis for this story, between Judy, an attractive little thing, shapely and with the added effect of some highly-realistic heavy breathing, and Punchy, a kid of the streets with patches on his pants, in a tenement-laden urban tough neighborhood. He’s not the only one with eyes for Judy, who moons for romance on an upper-story fire escape. The toughest kid on the block tries to impress with muscles. The rich kid from across the tracks (although he dresses like Little Lord Fauntleroy), comes equipped with an entourage of servants bearing expensive trinkets and candies for Judy. A street-wise narrator observes that Punchy can only offer “nothin’ but nothin’”. Stoop-shouldered and dejected, Punchy can only feel small – and smaller – and smaller, shrinking to the size of a tossed-away cigar butt as he mopes his way down the street.

A voice addresses him about his “dragging morale”. To Punchy’s surprise, the voice comes from a proud-looking horse, wearing an old, somewhat battered straw hat. The horse not only talks, but wears a chest of medals, announcing that he’s won the Kentucky Derby four times, the Santa Anita Handicap three times, and even appeared on the “Quiz Kids” radio program! The horse confesses, however, that he really didn’t do all that, any more than he can really talk – “It’s just the hat that does it. It brings out my suppressed desires. Confidentially, the hat’s full of dreams.” To boost Punchy’s spirits, the horse offers Punchy “a go at it”, a chance to try the hat on. As soon as Punchy lifts the hat from the horse’s brow, the noble steed reverts to a standard junkyard horse, with all medals and trappings gone. Not quite knowing what to expect, Punchy places the hat on his own head. In a twinkling, we are presented with a stop-motion rendering as close as possible to Paramount’s standard, “It’s a bird, It’s a plane” opening for a Superman cartoon – and Punchy is transformed by his own hidden dreams into a junior Superman, complete with the trademark shield across his chest. Punchy can now fly to Judy’s balcony without that feeling of being little any more, and impresses her enough that she presents him with a flower. He does the outrun the bullet bit, holds back a locomotive with one hand, then pulls a change of persona, transforming himself into Aladdin, so he can not only outdo the neighborhood tough guy with his feats of super strength, but show up the rich kid by materializing a balcony full of expensive gifts, including a new sporty coupe, a grand piano, and – most impressive to Judy of all – nylons! Unfortunately, a fire-escape of heavy gifts is not the greatest idea for structural soundness – and the whole load collapses onto a cop on the beat below. On top of that, the hat drops off Punchy’s head in the fall, transforming him back to his powerless, unimpressive self. Taking several items, including the hat, as evidence, the cop carries Punchy away to tell it to the judge.

A voice addresses him about his “dragging morale”. To Punchy’s surprise, the voice comes from a proud-looking horse, wearing an old, somewhat battered straw hat. The horse not only talks, but wears a chest of medals, announcing that he’s won the Kentucky Derby four times, the Santa Anita Handicap three times, and even appeared on the “Quiz Kids” radio program! The horse confesses, however, that he really didn’t do all that, any more than he can really talk – “It’s just the hat that does it. It brings out my suppressed desires. Confidentially, the hat’s full of dreams.” To boost Punchy’s spirits, the horse offers Punchy “a go at it”, a chance to try the hat on. As soon as Punchy lifts the hat from the horse’s brow, the noble steed reverts to a standard junkyard horse, with all medals and trappings gone. Not quite knowing what to expect, Punchy places the hat on his own head. In a twinkling, we are presented with a stop-motion rendering as close as possible to Paramount’s standard, “It’s a bird, It’s a plane” opening for a Superman cartoon – and Punchy is transformed by his own hidden dreams into a junior Superman, complete with the trademark shield across his chest. Punchy can now fly to Judy’s balcony without that feeling of being little any more, and impresses her enough that she presents him with a flower. He does the outrun the bullet bit, holds back a locomotive with one hand, then pulls a change of persona, transforming himself into Aladdin, so he can not only outdo the neighborhood tough guy with his feats of super strength, but show up the rich kid by materializing a balcony full of expensive gifts, including a new sporty coupe, a grand piano, and – most impressive to Judy of all – nylons! Unfortunately, a fire-escape of heavy gifts is not the greatest idea for structural soundness – and the whole load collapses onto a cop on the beat below. On top of that, the hat drops off Punchy’s head in the fall, transforming him back to his powerless, unimpressive self. Taking several items, including the hat, as evidence, the cop carries Punchy away to tell it to the judge.

In court, an ornery and cantankerous judge (voiced by Pinto Colvig, in his deep gruff register similar to Grumpy) calls Punchy forward to plead his defense, while Judy sits among the spectators. Punchy calls as surprise witness the junkyard horse, who at first can do nothing but stand there, until Punchy pleads for the judge to permit him to have his hat back. As the hat touches the horse’s brow again, he returns to the mode of the talking champion, and asks if the judge is familiar with the United States Supreme Court decision of Dream Horse vs. Night Mare, in which controlling precedent was set that dreams are quite legal. The judge claims he wouldn’t believe a horse’s word for it, even under oath. “I’m dubious”, he says. “Hello, dubious”, says the horse, and suggests he try the hat on himself to prove the point, just for kicks. The judge believes it ridiculous – but is transformed by the hat into a six-gun toting Western lawman. His bullet fire causes the hat to fly off and land on the arresting officer – who is embarrassingly transformed into a ballet dancer. The hat flies off again, and lands upon various members of the jury, transforming them into their dreams of being an opera singer, a fighting soldier, and even a human cannonball. The only person in the court who returns things to a semblance of order is Judy – who doesn’t have to dream about being anything but Judy, having everything in the first place, so that the hat causes no transformation at all. Punchy is freed, and returns the hat to the horse, who becomes Punchy and Judy’s private steed for romantic evening rides in the junk wagon. Judy is now fully satisfied with Punchy as he is, as he’s her dream.

In court, an ornery and cantankerous judge (voiced by Pinto Colvig, in his deep gruff register similar to Grumpy) calls Punchy forward to plead his defense, while Judy sits among the spectators. Punchy calls as surprise witness the junkyard horse, who at first can do nothing but stand there, until Punchy pleads for the judge to permit him to have his hat back. As the hat touches the horse’s brow again, he returns to the mode of the talking champion, and asks if the judge is familiar with the United States Supreme Court decision of Dream Horse vs. Night Mare, in which controlling precedent was set that dreams are quite legal. The judge claims he wouldn’t believe a horse’s word for it, even under oath. “I’m dubious”, he says. “Hello, dubious”, says the horse, and suggests he try the hat on himself to prove the point, just for kicks. The judge believes it ridiculous – but is transformed by the hat into a six-gun toting Western lawman. His bullet fire causes the hat to fly off and land on the arresting officer – who is embarrassingly transformed into a ballet dancer. The hat flies off again, and lands upon various members of the jury, transforming them into their dreams of being an opera singer, a fighting soldier, and even a human cannonball. The only person in the court who returns things to a semblance of order is Judy – who doesn’t have to dream about being anything but Judy, having everything in the first place, so that the hat causes no transformation at all. Punchy is freed, and returns the hat to the horse, who becomes Punchy and Judy’s private steed for romantic evening rides in the junk wagon. Judy is now fully satisfied with Punchy as he is, as he’s her dream.

“Enemies of Democracy – Beware!”

Further along in his flight, Snafu spots an armored vehicle below. “A lumbering Japanese tank”, concludes Snafu. He attacks the vehicle with a king-size can opener and plunger, prying off the top and plunging out its occupant – who is actually an American four-star general in a command tank. While Snafu salutes and attempts to sputter out a feeble explanation, a real enemy force is finally sighted – a squadron of “Messerschmitts. A whole mess of Messerschmitts” (a line also used by Freleng in “Daffy the Commando”). Realizing the planes are headed to bomb a nearby port, Snafu flies to the rescue, intercepting every bomb before it hits the ground, then piling the bombs neatly on a dock. “There. As harmless as a burnt-out match.” Snafu should have used his Super x-ray vision – as the camera does – revealing that the bombs are not concussion bombs, but include clocks for delayed timing. BOOOOOOMMMMMM!! Our scene changes to a bed in a field hospital, with Snafu well laid up on sick call. Technical Fairy materializes again, and asks if there’s anything he can get for him. Snafu weakly whispers, “Well…..Yes…..”, then shouts at the top of his lungs, “GET ME A FIELD MANUAL!!!’ as we iris out.

In Gas (Warner, Private Snafu, May, 1944, Chuck Jones, dir.), a brief, unexpected cameo occurs, as Snafu attempts to comply with a drill sergeant’s instruction on the use of a gas mask, by reaching into his pack for his equipment. Instead of retrieving the mask, he at first pulls out a woman’s brassiere (presumably an intended gift for the ladies, then pulls out none other than Bugs Bunny, who responds with his usual “Eh, what’s up, doc?” before being quickly discarded by Snafu.

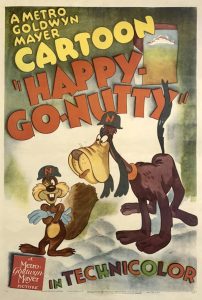

Happy Go Nutty (MGM. Screwy Squirrel, 6/24/44 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Well, it was only a matter of time (and not long at that, this being only his second cartoon) before Screwy Squirrel was institutionalized. Screwy is now a resident of the Crackpot County nut house, aka Moron Manor. The institution’s multiple buildings even include unique architecture, each one shaped like a letter, spelling the word “NUTZ”. However, the place could hardly qualify as a maximum-security asylum. Screwy appears inside a cell – but the barred door isn’t even locked, permitting Screwy to open the door to peer around the corridor to see if the coast is clear. Then, just to do things right, Screwy darts back inside the cell, shuts the door, and produces a hacksaw to cut an exit through the bars. Similarly, he races outside, to scramble over the main gate – taking no notice that the opposite half of the gate is resting wide open. Once outside, Screwy confides to us that the guys in this place think he’s crazy. He instantly dons a Napoleon hat, starts making faces to the camera, and conking himself on the head with a mallet, completing his sentence: “And I am, too.”

Happy Go Nutty (MGM. Screwy Squirrel, 6/24/44 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Well, it was only a matter of time (and not long at that, this being only his second cartoon) before Screwy Squirrel was institutionalized. Screwy is now a resident of the Crackpot County nut house, aka Moron Manor. The institution’s multiple buildings even include unique architecture, each one shaped like a letter, spelling the word “NUTZ”. However, the place could hardly qualify as a maximum-security asylum. Screwy appears inside a cell – but the barred door isn’t even locked, permitting Screwy to open the door to peer around the corridor to see if the coast is clear. Then, just to do things right, Screwy darts back inside the cell, shuts the door, and produces a hacksaw to cut an exit through the bars. Similarly, he races outside, to scramble over the main gate – taking no notice that the opposite half of the gate is resting wide open. Once outside, Screwy confides to us that the guys in this place think he’s crazy. He instantly dons a Napoleon hat, starts making faces to the camera, and conking himself on the head with a mallet, completing his sentence: “And I am, too.”

Meathead the dog plays security guard here, and embarks on one of those never-ending chases to return Screwy to incarceration. That’s all you need for plot in an Avery-gag-filled world. Screwy’s twin brother makes a reappearance, inside Meathead’s bag while Screwy himself stands safely outside. But Meathead is now prepared for such event, and deposits the twin into a trash can marked “For extra squirrels.” Meathead then complains to Screwy, “This picture is screwy enough without two of ya.” The two of them run into a dark cave, their images on screen fading darker and darker, until the screen is totally black. Some wild sound effects suggest the action of Meathead getting clobbered in some violent way. A match lights in the darkness, and the form of Screwy is illuminated, as he addresses the audience again. “Sure was a funny gag. Too bad you couldn’t see it.” Finally, our pair race across a panning background, and pass a blue backdrop on which appear the words, “The End.” Screwy slams on the brakes, pointing out to Meathead, “That was the end of the picture.” They slowly walk back to the backdrop, and Meathead observes, “Yep, that’s it all right.” The two shake hands as if sportsmanlike competitors at the end of a game, and prepare to depart their separate ways. Screwy pauses and turns, inquiring, “Before you leave, just what was the idea of chasing me all through the picture?” Meathead answers, “Because you’re crazy. You think you’re Napoleon. But ya ain’t. I am!” Meathead lapses into the same acts of insanity as Screwy, donning a hat, conking himself on the head with a mallet, kissing Screwy, and riding a child’s horse-head on a pole right through the backdrop and back to the asylum. Screwy turns to the audience for the final curtain line: “You know, I like this ending. It’s silly.” (Obviously, someone else did, too, as about a decade later, a watered-down variation on the ending would appear in Friz Freleng’s “Napoleon Bunny-Parte”, with far less comic impact.

Meathead the dog plays security guard here, and embarks on one of those never-ending chases to return Screwy to incarceration. That’s all you need for plot in an Avery-gag-filled world. Screwy’s twin brother makes a reappearance, inside Meathead’s bag while Screwy himself stands safely outside. But Meathead is now prepared for such event, and deposits the twin into a trash can marked “For extra squirrels.” Meathead then complains to Screwy, “This picture is screwy enough without two of ya.” The two of them run into a dark cave, their images on screen fading darker and darker, until the screen is totally black. Some wild sound effects suggest the action of Meathead getting clobbered in some violent way. A match lights in the darkness, and the form of Screwy is illuminated, as he addresses the audience again. “Sure was a funny gag. Too bad you couldn’t see it.” Finally, our pair race across a panning background, and pass a blue backdrop on which appear the words, “The End.” Screwy slams on the brakes, pointing out to Meathead, “That was the end of the picture.” They slowly walk back to the backdrop, and Meathead observes, “Yep, that’s it all right.” The two shake hands as if sportsmanlike competitors at the end of a game, and prepare to depart their separate ways. Screwy pauses and turns, inquiring, “Before you leave, just what was the idea of chasing me all through the picture?” Meathead answers, “Because you’re crazy. You think you’re Napoleon. But ya ain’t. I am!” Meathead lapses into the same acts of insanity as Screwy, donning a hat, conking himself on the head with a mallet, kissing Screwy, and riding a child’s horse-head on a pole right through the backdrop and back to the asylum. Screwy turns to the audience for the final curtain line: “You know, I like this ending. It’s silly.” (Obviously, someone else did, too, as about a decade later, a watered-down variation on the ending would appear in Friz Freleng’s “Napoleon Bunny-Parte”, with far less comic impact.

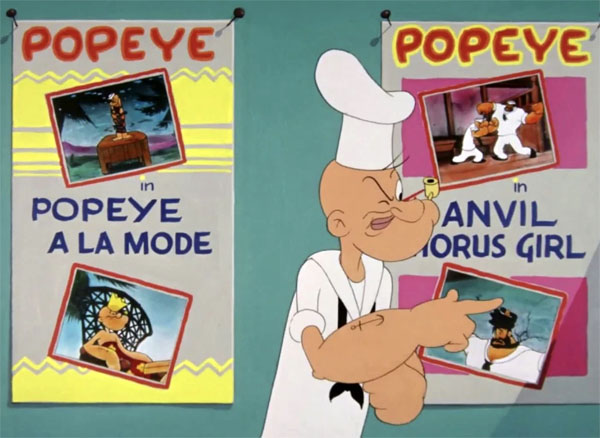

There were a good many Popeye “cheaters” produced over the years in the wake of Adventures of Popeye, discussed in an earlier installment of this trail. I thought I’d attempt to cover them all in one breath, in this installment coinciding with the release of one of the better ones. In each of these films, Popeye, and often Bluto, are fully aware of their film careers, and usually make a point of showing off clips from their old pictures to demonstrate their prowess or otherwise prove a point. Sometimes, the new wraparound animation used to disguise a clipfest could be based on the weakest of premises, and seemed to add little in the way of a new story.

from “Spinach Vs. Hamburgers” (1948)

Examples I would more or less classify in such category would include two Fleischers I bypassed, I’m In the Army Now (12/25/36 – Olive wants a man in uniform, but the cartoon army amazingly only has room for one toughest recruit. Did something happen to the military budget?); and Customers Wanted (1/27/39 – Bluto and Popeye run competing penny arcades, each specializing in showing only the clips of themselves from prior films, and vying for the patronage of Wimpy (remade in color as Penny Antics (3/11/55)). Other later weak entries included Spinach vs. Hamburgers (8/27/48 – Popeye uses film clips to try to convince the nephews to eat spinach at his eatery to get strong, rather than hamburgers at Wimpy’s competing restaurant); Popeye’s Premiere (3/25/45 – Popeye attends a premiere of his own picture – a condensed, redubbed edition of Fleischer’s Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp), Popeye Makes a Movie (8/11/50 – the nephews visit Popeye on the movie set where he is shooting Fleischer’s “Ali Baba’s Forty Thieves”); Big Bad Sinbad (12.12/52 – Popeye recounts to his nephews his adventure in “Popeye Meets Sinbad the Sailor”, to disprove a museum statue claiming Sinbad was the world’s greatest sailor); Popeye’s 20th Anniversary (4/2/54 – old clops are shown at a star-studded gala for Popeye attended by numerous Paramount stars); and The Crystal Brawl 4/5/57 – old clips are shown as if foretelling the future inside Popeye’s crystal ball).

One marginally better “cheater” which I will not specially feature here was Assault and Flattery (7/6/56), where Bluto uses clips in a courtroom setting in attempt to obtain a favorable verdict in a faked personal injury lawsuit against Popeye before Judge Wimpy.

Two “cheaters” which I tended to like better than the others for a little creativity in their story ideas receive featured status here. Early in Technicolor production appeared Spinach-Packin’ Popeye (Paramount/Famous, 7/21/44 – I. Sparber, dir.). Since they were just starting regular color production, what could you use for old clips this early? Why, of course, highlights from two of the three Technicolor specials Fleischer produced – for once with their superior original soundtracks (including the final battle from “Ali Baba” in complete form and in sync, unlike the broken soundtrack negative of the original that threw synchronization off for the last two or so minutes of all but recently restored TV prints). Perhaps this chance to see the film’s ending in corrected form was one of the principal attractions as to why I looked forward to screenings of this short. Yet it can also be said that the wraparound story was creative. Popeye, seeing his patriotic duty during wartime, has become a blood donor at a Red Cross Blood Bank (1 pint opens an account). Popeye, however, trusting in his usually-limitless strength, has overdone it, donating a gallon of blood, yet refusing to follow the nurse’s advice to lay in a hospital bed and get some rest, insisting he has an important fight on tonight to attend to. Popeye has obviously chosen the wrong day to become a donor, though he practices jabs and sparring as if nothing has phased him. The next thing you know, he is in a corner of a boxing ring, taking bows before the crowd, while his challenger Bluto the Bruiser limbers up in the opposite corner. The bell is sounded to start the first round (rung by a clapper shaped like a socking fist). The action shifts from the ring to a radio set in Olive Oyl’s house, where she, dressed in a nautical suit in support of “her man”., listens nervously to the blow-bi-blow description ot the fight. She pantomimes the actions described, succeeding in tying herself into pretzel knots. A fighter goes down, and so does Olive for the count. “He’s out”, shouts the announcer. Olive presumes she knows who is being talked about, and breaks into a cheer, presuming Bluto is lying on the canvas. Suddenly the announcer clarifies, by referring to the fight as a “stunning upset” – Popeye has been knocked cold! “WHAT!!!”, shrieks a shocked Olive.

Two “cheaters” which I tended to like better than the others for a little creativity in their story ideas receive featured status here. Early in Technicolor production appeared Spinach-Packin’ Popeye (Paramount/Famous, 7/21/44 – I. Sparber, dir.). Since they were just starting regular color production, what could you use for old clips this early? Why, of course, highlights from two of the three Technicolor specials Fleischer produced – for once with their superior original soundtracks (including the final battle from “Ali Baba” in complete form and in sync, unlike the broken soundtrack negative of the original that threw synchronization off for the last two or so minutes of all but recently restored TV prints). Perhaps this chance to see the film’s ending in corrected form was one of the principal attractions as to why I looked forward to screenings of this short. Yet it can also be said that the wraparound story was creative. Popeye, seeing his patriotic duty during wartime, has become a blood donor at a Red Cross Blood Bank (1 pint opens an account). Popeye, however, trusting in his usually-limitless strength, has overdone it, donating a gallon of blood, yet refusing to follow the nurse’s advice to lay in a hospital bed and get some rest, insisting he has an important fight on tonight to attend to. Popeye has obviously chosen the wrong day to become a donor, though he practices jabs and sparring as if nothing has phased him. The next thing you know, he is in a corner of a boxing ring, taking bows before the crowd, while his challenger Bluto the Bruiser limbers up in the opposite corner. The bell is sounded to start the first round (rung by a clapper shaped like a socking fist). The action shifts from the ring to a radio set in Olive Oyl’s house, where she, dressed in a nautical suit in support of “her man”., listens nervously to the blow-bi-blow description ot the fight. She pantomimes the actions described, succeeding in tying herself into pretzel knots. A fighter goes down, and so does Olive for the count. “He’s out”, shouts the announcer. Olive presumes she knows who is being talked about, and breaks into a cheer, presuming Bluto is lying on the canvas. Suddenly the announcer clarifies, by referring to the fight as a “stunning upset” – Popeye has been knocked cold! “WHAT!!!”, shrieks a shocked Olive.

As Olive kicks her foot through the radio speaker in disgust at her “weakling” boyfriend, there is a knock at the door. It is Popeye, who has revived, but presents himself with a blackened eye that appears to have the rings of an archery bulls-eye target. Olive calls him a “palooka”, and accuses him of having lost his strength. She disappears behind a folding dressing curtain, and changes from nautical outfit to the uniform of a WAC, claiming she’s through with the Navy, then turns a picture frame on a bureau around, hiding Popeye’s picture, and displaying one of Bluto in an army uniform (which picture gives Olive a wink). Popeye reaches inside his shirt for a scrapbook he keeps for just such an emergency, reminding Olive that he’s licked guys a hundred times better before. Still photos in the scrapbook come to life, to show his past exploits with Sinbad and with the Forty Thieves. While the clips are impressive, Olive still holds firm to her opinion, picking up Popeye by the chin with one finger. “You may have been strong then, but you’re just a weakling now. Good bye!” She tosses Popeye across the room, and Popeye lands prone across the sofa. Suddenly, the scene dissolves, and we return to the hospital bed in the blood bank where we found Popeye in the first place. A nurse is attempting to awaken him. It seems that Popeye took the advice to rest after all, and we have been witnessing his plasma-deprived dream. Popeye retains a consciousness of the dream, and the way Olive treated him, and races to her house to see where he really stands with her. Arriving at the home, Popeye calls to Olive in an upper-story window. When Olive peers out, Popeye picks up the entire house, right off its foundation. “Olive, don’t you think I’m a strong man?”, says Popeye, shaking the building until Olive falls out of the window, to be caught on one finger by Popeye. Olive responds, “You’re just about the strongest man in the whole wide world.” “That’s all I wants to know”, laughs a happy Popeye, his confidence in himself fully restored.

As Olive kicks her foot through the radio speaker in disgust at her “weakling” boyfriend, there is a knock at the door. It is Popeye, who has revived, but presents himself with a blackened eye that appears to have the rings of an archery bulls-eye target. Olive calls him a “palooka”, and accuses him of having lost his strength. She disappears behind a folding dressing curtain, and changes from nautical outfit to the uniform of a WAC, claiming she’s through with the Navy, then turns a picture frame on a bureau around, hiding Popeye’s picture, and displaying one of Bluto in an army uniform (which picture gives Olive a wink). Popeye reaches inside his shirt for a scrapbook he keeps for just such an emergency, reminding Olive that he’s licked guys a hundred times better before. Still photos in the scrapbook come to life, to show his past exploits with Sinbad and with the Forty Thieves. While the clips are impressive, Olive still holds firm to her opinion, picking up Popeye by the chin with one finger. “You may have been strong then, but you’re just a weakling now. Good bye!” She tosses Popeye across the room, and Popeye lands prone across the sofa. Suddenly, the scene dissolves, and we return to the hospital bed in the blood bank where we found Popeye in the first place. A nurse is attempting to awaken him. It seems that Popeye took the advice to rest after all, and we have been witnessing his plasma-deprived dream. Popeye retains a consciousness of the dream, and the way Olive treated him, and races to her house to see where he really stands with her. Arriving at the home, Popeye calls to Olive in an upper-story window. When Olive peers out, Popeye picks up the entire house, right off its foundation. “Olive, don’t you think I’m a strong man?”, says Popeye, shaking the building until Olive falls out of the window, to be caught on one finger by Popeye. Olive responds, “You’re just about the strongest man in the whole wide world.” “That’s all I wants to know”, laughs a happy Popeye, his confidence in himself fully restored.

Out of chronological sequence, we also have another Popeye “cheater” with some originality, Friend or Phoney (6/30/52 – I. Sparber, dir.). Popeye is sound asleep on his original “water bed” – a tub of water placed between a headboard and footboard, on which floats a small rowboat in which sleeps Popeye – when there is a knock at the door. A telegram is slipped through the mail slot. It is from Bluto, reading, “Am dying from your last beating. It’s your fault. Good bye forever.” Though Popeye insists to himself that he only acted in self-defense, he hastens to Bluto’s home to investigate. Bluto meanwhile chortles to himself at his ingenious idea, having sent the phoney telegram, and setting himself up in bed with bandages around his head, and removable plaster casts for both arms and one leg, the latter which he suspends in traction. When Popeye’s knock is heard, he weakly responds, “Come in.” Popeye is saddened at the sorry state in which Bluto appears. Bluto states that he does not blame Popeye himself, but the killer spinach that was inside him at the time of the battle. Using film clips which come to life from old movie posters on Bluto’s wall, Bluto reminds Popeye of their battles in previous pictures, and of the disastrous results to Bluto each time Popeye took his spinach. “Before you kill somebody else, throw away your spinach.” Popeye again proclaims it was self-defense, but Bluto classifies it as “just plain murder”. Bluto repeats his wish as a dying request to Popeye, then fakes a final death cry, collapsing rigidly upon the bed, and placing a lily upon his own chest. Popeye covers Bluto with the blanket, then trudges to the window, resolute that he cannot refuse a human his dying request. With heavy heart, Popeye flings his spinach can out the window. It lands in the rear of a passing truck which rolls away.

Out of chronological sequence, we also have another Popeye “cheater” with some originality, Friend or Phoney (6/30/52 – I. Sparber, dir.). Popeye is sound asleep on his original “water bed” – a tub of water placed between a headboard and footboard, on which floats a small rowboat in which sleeps Popeye – when there is a knock at the door. A telegram is slipped through the mail slot. It is from Bluto, reading, “Am dying from your last beating. It’s your fault. Good bye forever.” Though Popeye insists to himself that he only acted in self-defense, he hastens to Bluto’s home to investigate. Bluto meanwhile chortles to himself at his ingenious idea, having sent the phoney telegram, and setting himself up in bed with bandages around his head, and removable plaster casts for both arms and one leg, the latter which he suspends in traction. When Popeye’s knock is heard, he weakly responds, “Come in.” Popeye is saddened at the sorry state in which Bluto appears. Bluto states that he does not blame Popeye himself, but the killer spinach that was inside him at the time of the battle. Using film clips which come to life from old movie posters on Bluto’s wall, Bluto reminds Popeye of their battles in previous pictures, and of the disastrous results to Bluto each time Popeye took his spinach. “Before you kill somebody else, throw away your spinach.” Popeye again proclaims it was self-defense, but Bluto classifies it as “just plain murder”. Bluto repeats his wish as a dying request to Popeye, then fakes a final death cry, collapsing rigidly upon the bed, and placing a lily upon his own chest. Popeye covers Bluto with the blanket, then trudges to the window, resolute that he cannot refuse a human his dying request. With heavy heart, Popeye flings his spinach can out the window. It lands in the rear of a passing truck which rolls away.

The spinach can, with a design this time including a circular seal depicting an image of spinach-green within, has the seal develop into a living mouth, which calls out to Popeye, “You’ll be sorry!” As Popeye turns back into the room, he views the unexpected sight of Bluto, strong and well, holding the entire bed over his head, and smashing it down upon Popeye, until bedsprings pop out of Popeye’s ears. Bluto viciously yanks Popeye out from the bedding, and socks him a mighty blow out the window. Popeye bounces head over heels about a half-block, landing in a hole in a construction yard, partially-started through the force of a presently-idle pile driver. Bluto hurries to the cab of the machine, pulls the levers, and starts the machinery driving Popeye into the ground, through continuing pounding blows. The force of the blows begins to force wisps of smoke out of Popeye’s pipe, which travel through the air, spelling the letters “S. O. S.” The smoke letters reach the moving truck and the spinach can. The very-alive spinach can sniffs the air, inhaling the smoke to get the message. The can then forces itself to teeter, toppling itself from the truck bed, and rolling back to the construction yard where Popeye remains planted with only his head remaining above ground. The industrious spinach can doesn’t even wait for Popeye to figure out how to open it. Instead, it forces itself to pop open, shooting its vegetarian contents into Popeye’s mouth. Once chewed, the greenery does its work, transforming Popeye’s head into a form of solid iron. The next blow by the pile driver hits what is now an immovable object – causing the entire machinery to shatter as if just a toy. “Once again, I am saved by me spinach”, shouts Popeye, as a mighty sock from his fist shatters the cab of the pile driver, and another launches Bluto through the window of a real hospital, landing him into a sick bed. As Bluto’s eyes spin, Popeye comes a-visiting, bringing Bluto his own special version of flowers – fresh spinach sprouts growing in soil placed in a vase made of an empty spinach can. This is all Bluto can take, and he bursts out the hospital window in a state of insanity, racing away over the hills.

The spinach can, with a design this time including a circular seal depicting an image of spinach-green within, has the seal develop into a living mouth, which calls out to Popeye, “You’ll be sorry!” As Popeye turns back into the room, he views the unexpected sight of Bluto, strong and well, holding the entire bed over his head, and smashing it down upon Popeye, until bedsprings pop out of Popeye’s ears. Bluto viciously yanks Popeye out from the bedding, and socks him a mighty blow out the window. Popeye bounces head over heels about a half-block, landing in a hole in a construction yard, partially-started through the force of a presently-idle pile driver. Bluto hurries to the cab of the machine, pulls the levers, and starts the machinery driving Popeye into the ground, through continuing pounding blows. The force of the blows begins to force wisps of smoke out of Popeye’s pipe, which travel through the air, spelling the letters “S. O. S.” The smoke letters reach the moving truck and the spinach can. The very-alive spinach can sniffs the air, inhaling the smoke to get the message. The can then forces itself to teeter, toppling itself from the truck bed, and rolling back to the construction yard where Popeye remains planted with only his head remaining above ground. The industrious spinach can doesn’t even wait for Popeye to figure out how to open it. Instead, it forces itself to pop open, shooting its vegetarian contents into Popeye’s mouth. Once chewed, the greenery does its work, transforming Popeye’s head into a form of solid iron. The next blow by the pile driver hits what is now an immovable object – causing the entire machinery to shatter as if just a toy. “Once again, I am saved by me spinach”, shouts Popeye, as a mighty sock from his fist shatters the cab of the pile driver, and another launches Bluto through the window of a real hospital, landing him into a sick bed. As Bluto’s eyes spin, Popeye comes a-visiting, bringing Bluto his own special version of flowers – fresh spinach sprouts growing in soil placed in a vase made of an empty spinach can. This is all Bluto can take, and he bursts out the hospital window in a state of insanity, racing away over the hills.

Jasper Goes Hunting (Geroge Pal/Paramount, Madcap Models (Jasper and the Scarecrow), 7/29/44 – George Pal, dir.) – George Pal’s films usually weren’t self-referential as to their animated nature. It took another studio’s participation, and someone’s off-the-wall idea for it, to break that rule. In this rare episode, Jasper’s Mammy observes the same phenomena as usual. Every time she counts the chickens in the chicken coop, one is missing. The explanation is down the road a-piece. The Scarecrow is just polishing off the last morsels of meat from the last bones of a chicken carcass, nicely fried. The scarecrow’s talking crow partner looks on. “I sure do love my chicken”, says the Scarecrow. “You mean you loves your stomach”, quips the crow. To solve this problem, Mammy issues Jasper a rifle, and instructs him to use it if anyone tries messing with the chickens. As soon as Mammy leaves, Jasper imagines himself as a military commando in uniform, carrying an imaginary machine gun, and issues verbal commands to himself for a marching drill within the cabin. The Scarecrow takes a peek in the window to investigate the verbal activity. “Halt”, shouts Jasper, raising his weapon. The scarecrow quickly ducks below the window frame, waving his hat at the open window in the manner of a flag of truce, and telling Jasper to put that thing down before it goes off. The Scarecrow asks to examine the weapon, and after noting the bullets inside, concludes it is a mean -looking thing. To distract from the subject of Jasper’s guard duties, the Scarecrow begins weaving another of his tall tales, about the times he went big-game hunting. “He means crap-game hunting”, interrupts the crow, prompting the Scarecrow to shout at him, “QUIET!” The Scarecrow begins to describe his expedition, indicating that where objects in the cabin stand, various trees, rocks, etc. were present in the jungle. As each object is mentioned, they substitute in our view for the furnishings of the room, until the whole cabin disappears, and our three principal characters are surrounded by nothing but jungle – and the unseen wild animals within.

Jasper Goes Hunting (Geroge Pal/Paramount, Madcap Models (Jasper and the Scarecrow), 7/29/44 – George Pal, dir.) – George Pal’s films usually weren’t self-referential as to their animated nature. It took another studio’s participation, and someone’s off-the-wall idea for it, to break that rule. In this rare episode, Jasper’s Mammy observes the same phenomena as usual. Every time she counts the chickens in the chicken coop, one is missing. The explanation is down the road a-piece. The Scarecrow is just polishing off the last morsels of meat from the last bones of a chicken carcass, nicely fried. The scarecrow’s talking crow partner looks on. “I sure do love my chicken”, says the Scarecrow. “You mean you loves your stomach”, quips the crow. To solve this problem, Mammy issues Jasper a rifle, and instructs him to use it if anyone tries messing with the chickens. As soon as Mammy leaves, Jasper imagines himself as a military commando in uniform, carrying an imaginary machine gun, and issues verbal commands to himself for a marching drill within the cabin. The Scarecrow takes a peek in the window to investigate the verbal activity. “Halt”, shouts Jasper, raising his weapon. The scarecrow quickly ducks below the window frame, waving his hat at the open window in the manner of a flag of truce, and telling Jasper to put that thing down before it goes off. The Scarecrow asks to examine the weapon, and after noting the bullets inside, concludes it is a mean -looking thing. To distract from the subject of Jasper’s guard duties, the Scarecrow begins weaving another of his tall tales, about the times he went big-game hunting. “He means crap-game hunting”, interrupts the crow, prompting the Scarecrow to shout at him, “QUIET!” The Scarecrow begins to describe his expedition, indicating that where objects in the cabin stand, various trees, rocks, etc. were present in the jungle. As each object is mentioned, they substitute in our view for the furnishings of the room, until the whole cabin disappears, and our three principal characters are surrounded by nothing but jungle – and the unseen wild animals within.

The Scarecrow spots a set of tracks – no animal, but merely huge footprints that appear in the dirt, as if made by an invisible creature. Jasper and the Scarecrow follow them, while the crow perches upon the Scarecrow’s rifle barrel. The Scarecrow tells Jasper that they are only out to hunt the “big ones” – the bigger, the better. The crow is the only one of them to note that a huge elephant is following them, only a few paces behind. Zooming in fright to the Scarecrow’s shoulder, the crow asks “You say you like the big ones?” “Yeah, the great big ones”, responds the Scarecrow. “Well. That ain’t no hummingbird behind us”, warns the crow. In a twinkling, Scarecrow demonstrates how he “outsmarts” such animals – by merely beating a retreat into the highest and most distant tree.

The Scarecrow spots a set of tracks – no animal, but merely huge footprints that appear in the dirt, as if made by an invisible creature. Jasper and the Scarecrow follow them, while the crow perches upon the Scarecrow’s rifle barrel. The Scarecrow tells Jasper that they are only out to hunt the “big ones” – the bigger, the better. The crow is the only one of them to note that a huge elephant is following them, only a few paces behind. Zooming in fright to the Scarecrow’s shoulder, the crow asks “You say you like the big ones?” “Yeah, the great big ones”, responds the Scarecrow. “Well. That ain’t no hummingbird behind us”, warns the crow. In a twinkling, Scarecrow demonstrates how he “outsmarts” such animals – by merely beating a retreat into the highest and most distant tree.

The Scarecrow settles for smaller game, following a set of tracks to a hole in the ground. Pointing his rifle at the hole, the Scarecrow challenges, “I sees ya. Come on out and fight like a man. I got ya covered,” Of all people – er, animals – who should leap out but a 2-D fully animated Bugs Bunny – guest spotting in a film produced by a rival cartoon studio! This would be the only such instance of cross-pollination until the negotiation of the multi-studio contracts that produced the meeting of Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse in “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” Bugs nonchalantly leans on the Scarecrow’s gun, utters his trademark “What’s up, doc?”, and is verbally recognized by name by the Scarecrow. Bugs smiles modestly at the mention of his name, while music plays suggesting the Merrie Melodies theme without actually qioting it. But Bugs glances around and realizes something is wrong. “Hey. I’m in the wrong picture.” Bugs sheepishly waves a goodbye, then leaps back into the hole with a pop, leaving the intrepid hunters to simply stare at the hole, not quite sure whether to believe what just happened.

The hunt continues, as our heroes trek cautiously through the bush, but are spied upon by three natives, who smack their lips, suggesting they are cannibals. The Scarecrow assures Jasper that they should be running into an elephant to shoot any minute – and promptly walk right into the hind end of the one they encountered before. The Scarecrow adjusts a revolver-like switch on his rifle, altering bullet caliber by species until the reading “elephants” is reached. He raises the gun and takes careful aim at the unmissable target. Meanwhile the natives raise a long spear, and fling it at the Scarecrow. The spear narrowly misses the Scarecrow, overshooting him, to strike the elephant in the rear. The infuriated animal assumes our heroes to be responsible for the assault, and lowers his head in a stampeding charge after them. The Scarecrow and Jasper duck into a native straw hut. As the elephant reaches the hut with intent to trample it down, two stilts emerge from the base of the hut, raising the structure high above the elephant’s back. The elephant skids to a stop, reverses direction, and charges again. This time, he succeeds in picking up the hut on his back as he darts under the stilts. Jasper and the Scarecrow have a wild ride, until the roof of the hut catches on the limb of an overhanging tree, and the palm fronds and foliage providing the hut’s coverage fall away, leaving Jasper and the Scarecrow balanced atop a crossbar between the poles providing the hut’s framework, looking like they are the residents of a giant birdcage. Finally, everything falls from the tree, and the elephant catches up with them, grabbing them in his trunk, and flinging them into the sky. They sail through the air for miles, and land right back on Mammy’s farm, the Scarecrow and the crow on his shoulder smashing right through the roof of the chicken coop. Hearing the crash, Mammy arrives at the coop’s door, shotgun in hand. The Scarecrow sits on the floor, his face and outfit covered in broken eggs. Mammy concludes properly that Scarecrow was behind the chicken-stealing, and threatens to call the police. Scarecrow confides to the crow, “They can’t put you in jail for snitchin’ a little ol’ chicken.” The scene dissolves from the chicken coop to an identical pose of the Scarecrow, now wearing prison stripes, sitting behind bars in a cell. The camera pans to a small structure outside the jailhouse – a birdhouse, with iron bars across the doorway, in which crow sits incarcerated. Crow complains “I’m gonna write my congressman.” But the doors of the birdhouse merely close over the bars and the crow, revealing the Paramount logo etched thereon, for the fade out.

The hunt continues, as our heroes trek cautiously through the bush, but are spied upon by three natives, who smack their lips, suggesting they are cannibals. The Scarecrow assures Jasper that they should be running into an elephant to shoot any minute – and promptly walk right into the hind end of the one they encountered before. The Scarecrow adjusts a revolver-like switch on his rifle, altering bullet caliber by species until the reading “elephants” is reached. He raises the gun and takes careful aim at the unmissable target. Meanwhile the natives raise a long spear, and fling it at the Scarecrow. The spear narrowly misses the Scarecrow, overshooting him, to strike the elephant in the rear. The infuriated animal assumes our heroes to be responsible for the assault, and lowers his head in a stampeding charge after them. The Scarecrow and Jasper duck into a native straw hut. As the elephant reaches the hut with intent to trample it down, two stilts emerge from the base of the hut, raising the structure high above the elephant’s back. The elephant skids to a stop, reverses direction, and charges again. This time, he succeeds in picking up the hut on his back as he darts under the stilts. Jasper and the Scarecrow have a wild ride, until the roof of the hut catches on the limb of an overhanging tree, and the palm fronds and foliage providing the hut’s coverage fall away, leaving Jasper and the Scarecrow balanced atop a crossbar between the poles providing the hut’s framework, looking like they are the residents of a giant birdcage. Finally, everything falls from the tree, and the elephant catches up with them, grabbing them in his trunk, and flinging them into the sky. They sail through the air for miles, and land right back on Mammy’s farm, the Scarecrow and the crow on his shoulder smashing right through the roof of the chicken coop. Hearing the crash, Mammy arrives at the coop’s door, shotgun in hand. The Scarecrow sits on the floor, his face and outfit covered in broken eggs. Mammy concludes properly that Scarecrow was behind the chicken-stealing, and threatens to call the police. Scarecrow confides to the crow, “They can’t put you in jail for snitchin’ a little ol’ chicken.” The scene dissolves from the chicken coop to an identical pose of the Scarecrow, now wearing prison stripes, sitting behind bars in a cell. The camera pans to a small structure outside the jailhouse – a birdhouse, with iron bars across the doorway, in which crow sits incarcerated. Crow complains “I’m gonna write my congressman.” But the doors of the birdhouse merely close over the bars and the crow, revealing the Paramount logo etched thereon, for the fade out.

The Old Grey Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 10/28/44 – Robert Clampett, dir.), receives a very honorable mention. It is unclear with whom Elmer Fudd is interacting in the opening of this cartoon – a narrator, fate, or the voice of God. Nevertheless, it is evident that Elmer is aware that someone outside of his plane of existence is controlling his destiny. Elmer and Bugs also engage in various asides directly to the audience, a practice now becoming commonplace in Warner films, but with an extra twist at the end.

The Old Grey Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 10/28/44 – Robert Clampett, dir.), receives a very honorable mention. It is unclear with whom Elmer Fudd is interacting in the opening of this cartoon – a narrator, fate, or the voice of God. Nevertheless, it is evident that Elmer is aware that someone outside of his plane of existence is controlling his destiny. Elmer and Bugs also engage in various asides directly to the audience, a practice now becoming commonplace in Warner films, but with an extra twist at the end.

Elmer is first seen weeping, at how he’s “twied and twied”, but just never seems to catch that ol’ “wabbit”. Suddenly, a thunderbolt appears in the sky, and a voice is heard. “If at first you don’t succeed, Elmer, try, try again.” The puzzled Elmer looks skyward, questioning. “But how wong will it take?” “Let us look far into the future”, says the omniscient voice, and numbers begin to flash upon the screen, counting off decades, until the voice states, “When you hear the sound of the gong, it will be exactly 2000 A.D.” A loud bong shatters the numerical images, transporting us back to the same position we first saw Elmer in, but with several differences. Elmer first notices that he is “all winkled”. He now wears spectacles and has a small white moustache. Elmer checks a newspaper lying on the ground (The Daily Rocket), not only confirming the date, but reading startling news stories, including “Bing Crosby’s horse hasn’t come in yet (Bing’s bangtail bungles badly in stretch)”, and “Smellivision replaces Television) (with a curious sub-headline, reading “Carl Stalling sez it won’t work”). Other strange news stories, barely noticeable in the few seconds on screen, include “Treasury waves tax on free movie day”, and “Quintuplets give birth to quintuplets.” Elmer reaches for his “wifle”, but instead finds a futuristic weapon with a radio-style antenna and a barrel shaped like a small rocket booster, with an inscription identifying it as a Buck Rodgers Lightning-Quick Rabbit Killer. Now all Elmer needs to do is find Bugs. Not a problem, as Bugs pops up out of the ground right at Elmer’s side.

Bugs himself has undergone many changes, also wrinkled, wearing glasses, with stoop-shouldered posture, and a white goatee on his chin. Bugs alters his usual catch-phrase to suit the situation, greeting Elmer as “What’s up, Prune Face?” After the typical formalities (with Bugs putting a choke-hold on Elmer’s neck and smooching him on the lips), Bugs is off at “full speed ahead”, though at his advanced age, he is actually hobbling with a walking stick, and complaining to the audience about his lumbago. “Stop or I’ll shoot”, warns Elmer, and fires his new weapon, the recoil of which blasts him backwards into the trunk of a distant tree. He scores a direct hit on Bugs, as numbers light up around Bugs’s image like the scores of a pinball machine, followed by the word “Tilt”. Bugs literally “liquidates” momentarily, becoming a grey puddle on the ground, then transforming back into himself. Bugs begins another “Wild Hare” style prolonged death scene, which allows him opportunity to pass Elmer a photo album to keep for him, containing photos of the first time he and Elmer ever met, allowing for a cartoon-within-a-cartoon providing the first forecasting of “Baby Looney Tunes”, with Elmer and Bugs chasing as infants.

After the flashback, the scene returns to the “dying” Bugs, who begins to feebly sing “Memories”. “Oh, what have I done to you, old fwiend?”, moans Elmer. Bugs attempts to soothe Elmer’s distress by remarking “We all gotta go sometime. No tears, now”, and begins to give us the first signs that he might not be dying at all, as he rises from the ground, to begin digging his own grave! When the hole is finished, Bugs erects a headstone, reading “Rest in pieces”, steps into the hole, and begins to shake Elmer’s hand. Elmer, still weeping and with his eyes barely open, fails to notice as Bugs pivots, lifting Elmer into a position within the grave, then steps backwards to exit the hole himself. “Good bye, old fwiend”, wails Elmer in a final farewell. “So long, Methuselah”, wise-cracks Bugs, his voice now projected at full strength, as he vigorously propels rocks and dirt into the hole, completely burying Elmer six feet under. In a cutaway view through the Earth, we see Elmer trapped underground, who turns his head to address the audience. “Well, anyway, that pesky wabbit is outta my wife fowever and ever”, concludes Elmer. Suddenly, Bugs, ever the burrowing animal, pops into the small space with Elmer. “Well, now, I wouldn’t say that”, says Bugs, quoting the catchphrase of Mr. Peevey on “The Great Gildersleeve”, and places in Elmer’s hands a lit stick of dynamite, then disappears. Elmer is left holding the bag, cringing in terror as the scene quickly fades to black. The “That’s All Folks” end card appears on the screen, but is violently shaken by the sound of the unseen explosion below ground, before its final fade out.

After the flashback, the scene returns to the “dying” Bugs, who begins to feebly sing “Memories”. “Oh, what have I done to you, old fwiend?”, moans Elmer. Bugs attempts to soothe Elmer’s distress by remarking “We all gotta go sometime. No tears, now”, and begins to give us the first signs that he might not be dying at all, as he rises from the ground, to begin digging his own grave! When the hole is finished, Bugs erects a headstone, reading “Rest in pieces”, steps into the hole, and begins to shake Elmer’s hand. Elmer, still weeping and with his eyes barely open, fails to notice as Bugs pivots, lifting Elmer into a position within the grave, then steps backwards to exit the hole himself. “Good bye, old fwiend”, wails Elmer in a final farewell. “So long, Methuselah”, wise-cracks Bugs, his voice now projected at full strength, as he vigorously propels rocks and dirt into the hole, completely burying Elmer six feet under. In a cutaway view through the Earth, we see Elmer trapped underground, who turns his head to address the audience. “Well, anyway, that pesky wabbit is outta my wife fowever and ever”, concludes Elmer. Suddenly, Bugs, ever the burrowing animal, pops into the small space with Elmer. “Well, now, I wouldn’t say that”, says Bugs, quoting the catchphrase of Mr. Peevey on “The Great Gildersleeve”, and places in Elmer’s hands a lit stick of dynamite, then disappears. Elmer is left holding the bag, cringing in terror as the scene quickly fades to black. The “That’s All Folks” end card appears on the screen, but is violently shaken by the sound of the unseen explosion below ground, before its final fade out.

This short features marvelous and unusually-neat animation by Rod Scribner, wonderfully creative character re-designs, and is a memorable Clampett classic from start to finish. However, it is hard to imagine this script coming off with the same impact and appeal without the fully-developed, instantly recognizable personalities of its star characters. Half the magic of this cartoon rests in how well two true screen icons could be so vividly re-imagined.

Stage Door Cartoon (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 12/30/44 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir,) – A typical Bugs and Elmer chase leads through the stage entrance of a vaudeville theater. Bugs is soon on the stage in various roles and guises, impersonating a French can-can dancer, doing a specialty tap dance (in moves that would be remembered later as models for similar scenes in “Bugs Bunny Rides Again” and “Mississippi Hare”), and performing a concert piano number (predicting “Rhapsody Rabbit”), with Elmer inside the piano bouncing on the strings. After the curtain lowers, it rises for another act, revealing Elmer in the course of trying to strangle Bugs. Realizing he’s now in view of the paying customers, Elmer blushes many shades of color in embarrassment and stage fright. Bugs takes charge as emcee, and points out to the theater audience a high-diving platform that has been revealed behind the curtains from nowhere. Bugs begins to tout Elmer as his “partner”, who will make a death-defying dive from the platform’s dizzying heights. “Get goin’. They’re all lookin’ at ya’”, whispers Bugs to Elmer, prodding him into gullibly climbing up the ladder to the top of the theater (tall enough that it probably wouldn’t fit even in the Metropolitan Opera House.) While Elmer is busy climbing, he is oblivious to what Bugs is continuing to relate to the audience. “Now, ladies and gentlemen, my partner will NOT dive into the tank which you see here. Tell ya’ what he’s gonna do. He’s gonna dive into an ordinary glass of water!” Bugs makes the switch of water receptacles, just as Elmer cautiously reaches the platform above. Elmer backs onto the platform, then glances down. The shock of the view below teeters Elmer off the platform into an uncontrolled dive. All he has time to do on the way down is set himself in a position to make his last prayers to his maker. SPLASH! A close-up shows Elmer, with his face and half his torso tightly crammed into the small glass, while Bugs takes all the bows.

Stage Door Cartoon (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 12/30/44 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir,) – A typical Bugs and Elmer chase leads through the stage entrance of a vaudeville theater. Bugs is soon on the stage in various roles and guises, impersonating a French can-can dancer, doing a specialty tap dance (in moves that would be remembered later as models for similar scenes in “Bugs Bunny Rides Again” and “Mississippi Hare”), and performing a concert piano number (predicting “Rhapsody Rabbit”), with Elmer inside the piano bouncing on the strings. After the curtain lowers, it rises for another act, revealing Elmer in the course of trying to strangle Bugs. Realizing he’s now in view of the paying customers, Elmer blushes many shades of color in embarrassment and stage fright. Bugs takes charge as emcee, and points out to the theater audience a high-diving platform that has been revealed behind the curtains from nowhere. Bugs begins to tout Elmer as his “partner”, who will make a death-defying dive from the platform’s dizzying heights. “Get goin’. They’re all lookin’ at ya’”, whispers Bugs to Elmer, prodding him into gullibly climbing up the ladder to the top of the theater (tall enough that it probably wouldn’t fit even in the Metropolitan Opera House.) While Elmer is busy climbing, he is oblivious to what Bugs is continuing to relate to the audience. “Now, ladies and gentlemen, my partner will NOT dive into the tank which you see here. Tell ya’ what he’s gonna do. He’s gonna dive into an ordinary glass of water!” Bugs makes the switch of water receptacles, just as Elmer cautiously reaches the platform above. Elmer backs onto the platform, then glances down. The shock of the view below teeters Elmer off the platform into an uncontrolled dive. All he has time to do on the way down is set himself in a position to make his last prayers to his maker. SPLASH! A close-up shows Elmer, with his face and half his torso tightly crammed into the small glass, while Bugs takes all the bows.

Bugs next bamboozles Elmer as a stage dresser, transforming him into the costume of a Shakespearian actor. Pushed onto the stage, Elmer has no idea what to do. Bugs appears in a prompter’s box at the front of the stage, and prods Elmer to act, demonstrating the right moves. Then Bugs demonstrates the wrong moves, setting Elmer into a series of silly gestures and making faces at the audience. Bugs holds up to audience view a pair of signs, reading, “Silly, isn’y he?’ and “Well, what’re you waiting for?” Elmer promptly gets splattered in the face with an overripe tomato. The curtain falls, then rises to reveal Elmer, again attempting to get Bugs, but freezing as the audience’s eyes fall upon him again. Bugs shadows Elmer on stage, as an extra set of arms appears to reach out from behind Elmer, unbuttoning Elmer’s outfit and forcing him into a humiliating strip-tease down to his loose-fitting boxer shorts. Leaving Elmer on stage, the camera cuts away to a shot of Bugs in a dressing room, showing him donning a broad hat, coat, and moustache, assuming the disguise of a sheriff. A moment later, what appears to be the same “sheriff” marches onto the stage, arresting Elmer for indecent Southern exposure. Just as the two reach the theater aisle leading to the exit, a movie screen lowers, and, of all things, a Bugs Bunny cartoon begins to unreel for the patrons. The boisterous sheriff tells Elmer, “Sit, son. I ain’t a gonna miss this ‘un.” On the screen (projected in black and white, even though all Bugs cartoons were presently in color), we find they are apparently watching the same cartoon we are presently witnessing, as the shot of Bugs putting on the sheriff’s disguise is repeated. Elmer gets wise, and presumes that the sheriff is nothing but the “wabbit” in disguise. “Off with it, you twickster”, rants Elmer, tearing away at the sheriff’s clothes – only to find inside a real sheriff, also reduced to his boxer shorts. “You’ll swing for this, suh!” roars the sheriff, marching Elmer off to the clink. Below the stage, a pit orchestra plays the closing notes of a standard Warner cartoon fanfare (as if they’ve been playing the score live all along – decades before “Bugs Bunny on Broadway”). The maestro brings the performers to a stop, then faces the audience. It is Bugs, in yet another costume, ending with Jimmy Durante’s curtain line, “I got a million of ‘em.”

Bugs next bamboozles Elmer as a stage dresser, transforming him into the costume of a Shakespearian actor. Pushed onto the stage, Elmer has no idea what to do. Bugs appears in a prompter’s box at the front of the stage, and prods Elmer to act, demonstrating the right moves. Then Bugs demonstrates the wrong moves, setting Elmer into a series of silly gestures and making faces at the audience. Bugs holds up to audience view a pair of signs, reading, “Silly, isn’y he?’ and “Well, what’re you waiting for?” Elmer promptly gets splattered in the face with an overripe tomato. The curtain falls, then rises to reveal Elmer, again attempting to get Bugs, but freezing as the audience’s eyes fall upon him again. Bugs shadows Elmer on stage, as an extra set of arms appears to reach out from behind Elmer, unbuttoning Elmer’s outfit and forcing him into a humiliating strip-tease down to his loose-fitting boxer shorts. Leaving Elmer on stage, the camera cuts away to a shot of Bugs in a dressing room, showing him donning a broad hat, coat, and moustache, assuming the disguise of a sheriff. A moment later, what appears to be the same “sheriff” marches onto the stage, arresting Elmer for indecent Southern exposure. Just as the two reach the theater aisle leading to the exit, a movie screen lowers, and, of all things, a Bugs Bunny cartoon begins to unreel for the patrons. The boisterous sheriff tells Elmer, “Sit, son. I ain’t a gonna miss this ‘un.” On the screen (projected in black and white, even though all Bugs cartoons were presently in color), we find they are apparently watching the same cartoon we are presently witnessing, as the shot of Bugs putting on the sheriff’s disguise is repeated. Elmer gets wise, and presumes that the sheriff is nothing but the “wabbit” in disguise. “Off with it, you twickster”, rants Elmer, tearing away at the sheriff’s clothes – only to find inside a real sheriff, also reduced to his boxer shorts. “You’ll swing for this, suh!” roars the sheriff, marching Elmer off to the clink. Below the stage, a pit orchestra plays the closing notes of a standard Warner cartoon fanfare (as if they’ve been playing the score live all along – decades before “Bugs Bunny on Broadway”). The maestro brings the performers to a stop, then faces the audience. It is Bugs, in yet another costume, ending with Jimmy Durante’s curtain line, “I got a million of ‘em.”

• Watch the whole darn thing CLICK HERE.

NEXT WEEK: Sakes alive, it’s ‘45!