A surprise for Cartoon Research – an animator breakdown of a B&W Fleischer Popeye cartoon! Tom Johnson’s nephew, Andy Chance, was kind enough to lend the “director’s board,” which his uncle saved for decades.

A surprise for Cartoon Research – an animator breakdown of a B&W Fleischer Popeye cartoon! Tom Johnson’s nephew, Andy Chance, was kind enough to lend the “director’s board,” which his uncle saved for decades.

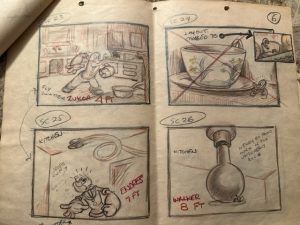

A “director’s board,” a working copy of the storyboard for Tom Johnson’s unit, contains thumbnail drawings reflecting the production storyboard, which was drawn in a different size. The director boards also demonstrate how Fleischer’s head animators (directors) planned and kept track of the animator assignments, footage, music tempo, and status of his sections.

Although Max Fleischer’s principal artists collaborated with a mixture of writers and animators from the West Coast in sunny Miami, their influence on the Fleischer product inarguably led to the cartoons’ sharp decline in quality, especially on Popeye the Sailor. In this cartoon, Popeye is continuously annoyed and outsmarted by a housefly—a comic situation more suited for a generic character than Paramount’s leading animated star. Furthermore, Popeye uses a shotgun to solve his problem during the climax rather than eating his spinach; instead, the fly consumes it halfway into the film.

Eric St. Clair (1902-1968) is credited on the story for Flies Ain’t Human, his only screen credit for Max Fleischer. Some of Eric’s family members shared artistic backgrounds: Eric’s father, Norman St. Clair, was a notable architect and watercolor artist in Laguna Beach, helping establish the coastal city as an artists’ colony. His brother, Mal St. Clair, worked as a newspaper cartoonist but chose a career in live-action comedy shorts; Mal St. Clair first worked as an actor, writer, and director for Mack Sennett, co-directed two of Buster Keaton’s independent shorts The Goat (1921) and The Blacksmith (1922), and helmed four Laurel and Hardy vehicles released by 20th Century Fox in the early 1940s. (Incidentally, Eric was the male lead in a feature directed by his brother, Find Your Man [1924], starring Rin Tin Tin.) Meanwhile, in the early 1930s, Eric became an illustrator and painter at Laguna Beach, relocating to Miami by 1935. He joined Max Fleischer’s studio by the summer of 1939; his contributions before Flies Ain’t Human are unknown.

Eric St. Clair (1902-1968) is credited on the story for Flies Ain’t Human, his only screen credit for Max Fleischer. Some of Eric’s family members shared artistic backgrounds: Eric’s father, Norman St. Clair, was a notable architect and watercolor artist in Laguna Beach, helping establish the coastal city as an artists’ colony. His brother, Mal St. Clair, worked as a newspaper cartoonist but chose a career in live-action comedy shorts; Mal St. Clair first worked as an actor, writer, and director for Mack Sennett, co-directed two of Buster Keaton’s independent shorts The Goat (1921) and The Blacksmith (1922), and helmed four Laurel and Hardy vehicles released by 20th Century Fox in the early 1940s. (Incidentally, Eric was the male lead in a feature directed by his brother, Find Your Man [1924], starring Rin Tin Tin.) Meanwhile, in the early 1930s, Eric became an illustrator and painter at Laguna Beach, relocating to Miami by 1935. He joined Max Fleischer’s studio by the summer of 1939; his contributions before Flies Ain’t Human are unknown.

Eric’s draft registration card, dated February 14, 1942, affirms that he had settled back to Laguna Beach and found a job at Columbia Pictures.

Besides Tom Johnson’s regular animators, George Germanetti, Frank Endres, and Harold Walker, Lou Zukor (1912-2004) also worked on the short. Zukor was one of many animation artists who flocked to Fleischer’s Miami studio from the West Coast, where Lou had prior experience working for Romer Grey, Charles Mintz, and Walter Lantz during the 1930s. At Fleischer, Zukor primarily worked in Orestes Calpini’s unit (his only Fleischer credit is on Nurse Mates [1940]). The director boards presented here reveal that he shifted to Tom Johnson’s unit. (Note, too, that Zukor draws Popeye with black pupils when the director’s board for Lou’s scenes insists otherwise.)

Flies Ain’t Human had its announced release on April 4, 1941. Later, the Popeye cartoon played in New York’s Paramount Theater during the week of June 21, along with the feature One Night in Lisbon, starring Fred MacMurray, Madeleine Carroll, and Patricia Morison. Then, Flies had a repeat booking at the Rialto on the week of October 11, with the Universal motion picture Flying Cadets as the feature presentation. Years later, at Famous Studios, Tom Johnson supervised a remake, The Fly’s Last Flight, released in 1949.

Here are the “director’s boards” – Click on the thumbnails to enlarge.

Thanks to Andy Chance for the production materials and to Michael Barrier, Mark Kausler, Mark Mayerson, Harvey Deneroff, and Bob Jaques for additional information.