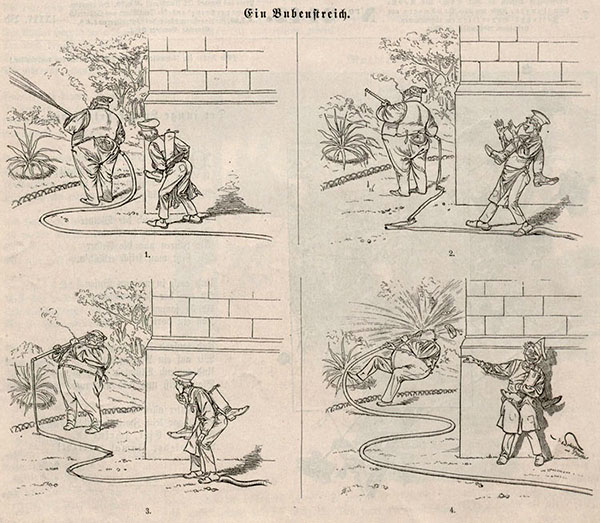

L’Arroseu

Comics and cartoons are first cousins. Developed more or less at the same time, they present a specular kinship not entirely free of animosity, in the manner of those eternal teenagers who kick each other under the table. But the Cinema, that respectable figure watching over the boys, is not much older and actually owes them more than he’d like to admit. After all, the first film with a fictional plot, the short “L’Arroseur arrosé”, by Louis and Auguste Lumière (1895), was nothing more than a comic page adaptation, and the whole cinema’s very act owes a lot to the “Théâtre Optique” of Émile Reynaud, creator of cartoons that predates any cinematographic work.

Happy Hooligan postcard (1906)

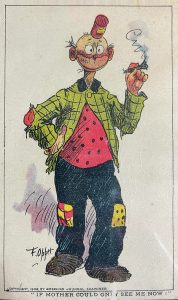

“Fortunello”, by Ettore Petrolini

Frederick Burr Opper (1857-1937) was one of the pioneers of American newspaper comic strips. His comic characters were featured in magazine gag cartoons, covers, political cartoons and comic strips for six decades, but perhaps his best remembered work is a comic strip about a funny hobo named Happy Hooligan, which appeared in print around 1900.

BELOW: Happy Hooligan film adaptation with actors in 1903.

BELOW: Happy Hooligan animated cartoon adaptation (1917).

Like the later Mutt and Jeff, Krazy Kat or George McManus’ regular cast, Happy Hooligan got a classic animated cartoon adaptation, being at the same time one of the first (if not the first) American comic strips to be known worldwide.

In Italy it was called Fortunello, and there it was read by the great comedian Ettore Petrolini (1884-1936), who adapted it for one of his stage acts around 1915.

Ettore Petrolini.

His Fortunello took the comic looks of Opper’s character, endowed with a personality closer to the taste of the futurists, who adopted the guy as a mascot of the whole movement. In any case, Petrolini’s Fortunello was more like a robot than a hobo, a representative of the future, the first pop hero to manifest himself as such. And he invented rap in passing.

Here, a film reconstruction of the act made by Petrolini in 1935 for his film “Nerone” (directed by Alessandro Blasetti). Note the particular emphasis on the “grotesque”, which was probably the most striking aspect of the new graphic language, before being replaced by something called “appeal”.

“Pancho Talero”, by Arturo Lanteri.

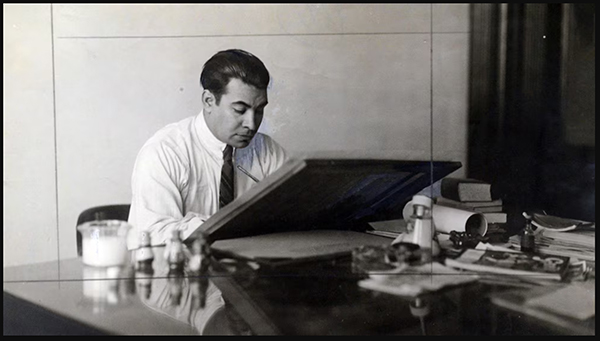

Arturo Lanteri

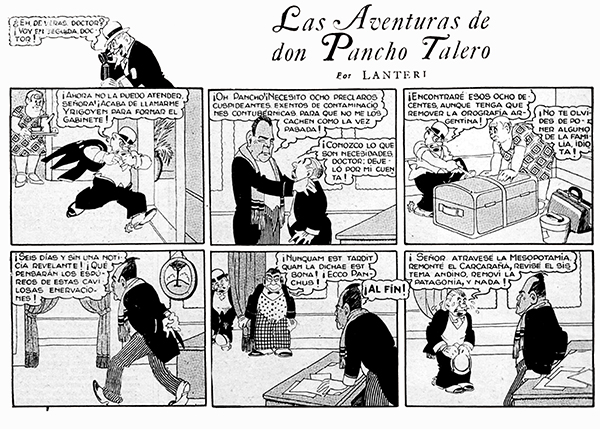

Arturo Lanteri (1891-1975) was the first Argentine cartoonist who can be said to have managed to turn his creations into a brand, an achievement perhaps shared with Diógenes Taborda (already mentioned in these columns). Lanteri’s star shone until it was somewhat eclipsed by the unstoppable Dante Quinterno -who, by some chance, had been assistant to both Lanteri and Taborda. His most popular creation was called “Las aventuras de Pancho Talero”, a family strip drawn in the tradition of George McManus’ “Bringing up Father”.

Pancho Talero’s comic strip.

Talero’s bunch had more pretensions than resources and tried to cope with the high classes -with uneven luck- under the iron rule of Mrs. Talero. The popularity of Lanteri’s creatures generated at the time a huge amount of merchandising and even three live action features, written and directed by Lanteri himself: “The Adventures of Pancho Talero” (1929), “Pancho Talero in the Stone Age” (1930) and “Pancho Talero in Hollywood” (1931).

Pancho Talero also got his own tango. Here’s the piece, illustrated with Lanteri’s production:

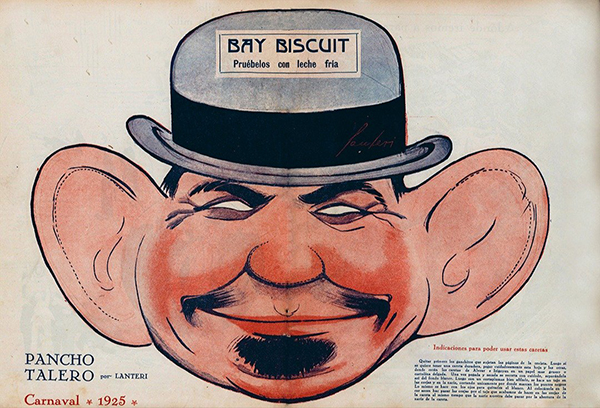

A Pancho Talero mask

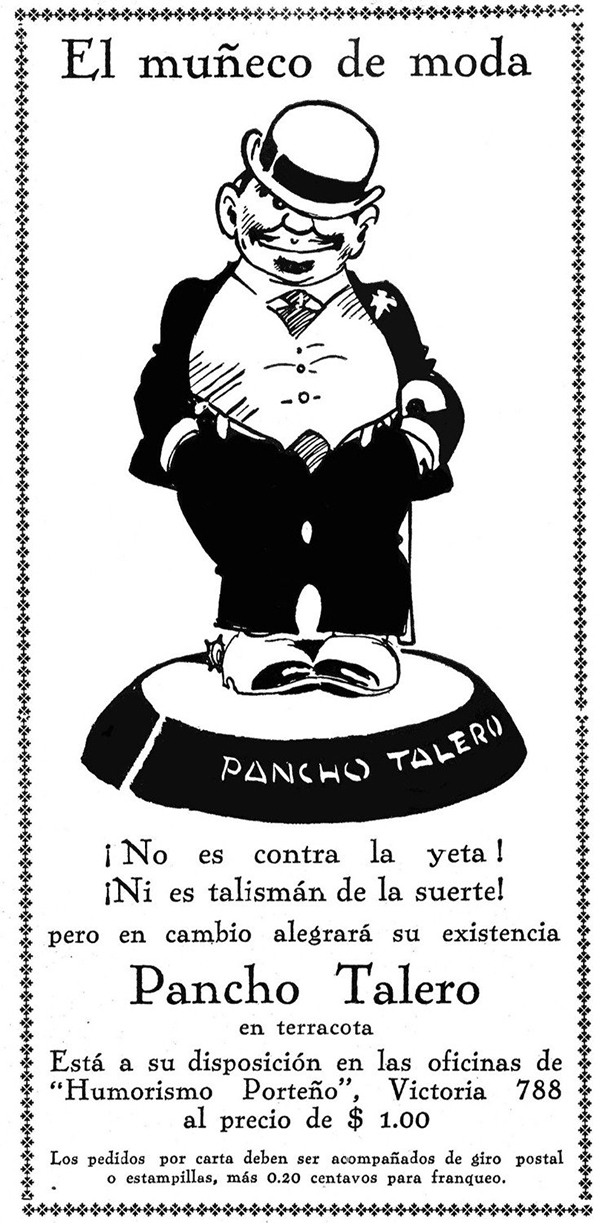

Pancho Talero’s merchandising.

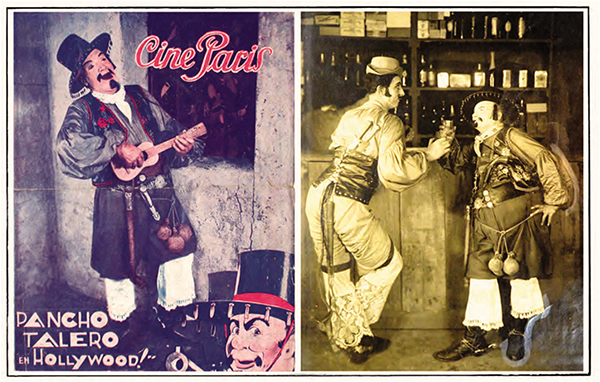

Since, as customary in Argentina, Lanteri’s films were lost, for a long time they were considered an extravagance designed to squeeze the popularity of the characters (all that was known about them was that “Pancho Talero in Hollywood” was a parody of Douglas Fairbanks’ “The Gaucho”, with a soundtrack added at the last minute).

Pancho Talero’s Fairbanks spoof.

However, a couple of decades ago, a ten-minute fragment of the second of these productions appeared in some vault. What remains of “Pancho Talero in the Stone Age” (“Pancho Talero en la prehistoria”) has something of Chaplin’s or Keaton’s incursions into the genre but it also shows that Lanteri was an excellent director, within a genre (as far as I know) absolutely unexplored in Argentine film production: the slapstick comedy. In any case, the discovery made doubly regret the loss of the rest of Lanteri’s film production.

One of Lanteri’s movie versions of Pancho Talero.

The crew of Lanteri’s cinematographic productions.

In the technical field of how to adapt to the screen a drawn character, Lanteri proposes a very simple device: Pepito Petray (as mr. Talero) wears a rigid mask with the character’s features printed on it. It works smoothly, against all odds.

Lanteri’s film (above)starts at 4’20’’, and the entrance of its title character happens at 10’30’’. For the Spanish speakers, Mr. Peña, our host, offers interesting additional details.

Of course, this brief detail does not imply that there are no weirder comic adaptations lurking just around the corner. We had better be cautious with our printed friends.