This week’s survey starts by backtracking to a Popeye overlooked last week, then traverses most of the year 1941. As may be expected, there are multiple visits with Tex Avery, king of breaking down the fourth wall and cartoon conventions. Also, some behind the scenes business at Disney, the inauguration of a franchise for Goofy, and the starring debut of Walter Lantz’s most durable personality.

It’s the Natural Thing To Do (Paramount, Popeye, 7/30/39 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Tom Johnson, Lod Rossner, anim.) – Popeye and Bluto are having an average day, battling each other in Olive’s yard and spraying logs from Olive’s woodpile in every direction, including through her kitchen window. Olive, completely used to this sort of thing, ducks periodically while washing the dishes, calling out the window, “Have a good time, but keep off of my flowers.” A messenger appears to deliver a telegram to Olive, and for his tip, the messenger receives a clunk on the head from one of the incoming logs at the window. Olive reads the telegram, then quickly rushes out the window to alert the boys of the news. The message is from the Popeye Fan Club, addressed to all of them. “We like your pictures but wish you would cut out the rough stuff once in a while and act more refined – Be ladies and gentlemen – That’s the natural thing to do.” After the signature, the message concludes, “P.S. Now go on with the picture.” Bluto is the first to react. “Gentlemen, eh? Must be a character part.” Popeye chimes in: “I can act rough, but what’s ruff-fined?” Olive insists she’ll take care of everything, and tells the boys to come back later – as gentlemen. Bluto and Popeye return that afternoon, decked out in tuxedos, tails, and top hats. Bluto graciously dusts off the doorbell button with a handkerchief before Popeye rings it. Olive awaits inside, gussied up in fashionable attire with oversized bracelets and earrings. She offers her two suitors a hand apiece to kiss, and they all minuet their way over to the easy chair and sofa to be seated. However, none of them are sure what to do next, and Popeye begins to nervously tug at his stiff collar, complaining how hot it is. Olive consults her book of etiquette for the next move, making special note of a random rule to never dunk your donuts beyond the elbow. Finally ready to proceed, Olive clangs a small table gong, signaling a hired maid to wheel in on a bicycle three tall stacks of teacups, plates, sandwiches and pastries. Popeye, Olive, and Bluto spend several frustrating moments attempting to balance the various courses of their repast atop their hands and laps, barely managing to partake of any of the beverages and goodies seated thereon. The tea is too hot for Popeye, producing steam out of his ears. Olive drops a donut on her skirt, but attempts to recover by flipping the donut upwards with a quick parting of her legs.

It’s the Natural Thing To Do (Paramount, Popeye, 7/30/39 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Tom Johnson, Lod Rossner, anim.) – Popeye and Bluto are having an average day, battling each other in Olive’s yard and spraying logs from Olive’s woodpile in every direction, including through her kitchen window. Olive, completely used to this sort of thing, ducks periodically while washing the dishes, calling out the window, “Have a good time, but keep off of my flowers.” A messenger appears to deliver a telegram to Olive, and for his tip, the messenger receives a clunk on the head from one of the incoming logs at the window. Olive reads the telegram, then quickly rushes out the window to alert the boys of the news. The message is from the Popeye Fan Club, addressed to all of them. “We like your pictures but wish you would cut out the rough stuff once in a while and act more refined – Be ladies and gentlemen – That’s the natural thing to do.” After the signature, the message concludes, “P.S. Now go on with the picture.” Bluto is the first to react. “Gentlemen, eh? Must be a character part.” Popeye chimes in: “I can act rough, but what’s ruff-fined?” Olive insists she’ll take care of everything, and tells the boys to come back later – as gentlemen. Bluto and Popeye return that afternoon, decked out in tuxedos, tails, and top hats. Bluto graciously dusts off the doorbell button with a handkerchief before Popeye rings it. Olive awaits inside, gussied up in fashionable attire with oversized bracelets and earrings. She offers her two suitors a hand apiece to kiss, and they all minuet their way over to the easy chair and sofa to be seated. However, none of them are sure what to do next, and Popeye begins to nervously tug at his stiff collar, complaining how hot it is. Olive consults her book of etiquette for the next move, making special note of a random rule to never dunk your donuts beyond the elbow. Finally ready to proceed, Olive clangs a small table gong, signaling a hired maid to wheel in on a bicycle three tall stacks of teacups, plates, sandwiches and pastries. Popeye, Olive, and Bluto spend several frustrating moments attempting to balance the various courses of their repast atop their hands and laps, barely managing to partake of any of the beverages and goodies seated thereon. The tea is too hot for Popeye, producing steam out of his ears. Olive drops a donut on her skirt, but attempts to recover by flipping the donut upwards with a quick parting of her legs.

The donut, however, flips onto her nose, a ringer in any horseshoe match. Popeye gets his finger stuck in a teacup handle, and when he pulls it loose, jabs Bluto, who spits out the cream from a filled cruller into Olive’s face. Bluto attempts an apology with unnaturally-long words, but Olive politely dismisses the incident, changing the subject to “Shall we converse a bit?” Bluto remarks that he’s heard that conversing is coming back, and Popeye claims it breaks up the monopoly of not talking. “Who will open?”, Olive asks. In the manner of a poker game, Bluto responds, “I’ll pass.” “They say language is used more for talkin’ than any other”, begins Popeye. Time passes slowly – so slow, the minute hand of the clock has to develop arms to drag the hour hand past the next hour mark. All of our participants still sit where they were, entirely listless, drooping, and without a thing to say. Popeye finally begins to chuckle to himself, then to laugh heartily, muttering how silly this gentleman stuff is. Bluto begins to join in the laughter, and soon Olive is tittering. She pulls out her etiquette book again, and remarks between giggles, “Etiquette – what a joke!”, tearing the book in two. Popeye continues to belly laugh, and in his reactive movements, accidentally lands a light blow to Bluto’s jaw. Bluto returns the favor, with a laughing jab at Popeye’s face. Soon, the two are jutting out their chins to take the inevitaable next blow, and Bluto finally smacks Popeye with a good one, sailing him across the room and through a framed picture, from which his feet appear, twitching in a manner resembling a Russian dancer. Soon, the boys are tossing furniture at each other. Bluto spins Popeye around on a piano stool, while Popeye delivers a mule kick to Bluto’s rear. Olive begins happily playing a flute in appreciation of the action. Popeye dodges Bluto’s throws of crockery, ducking in and out of a chest of drawers, while Olive cracks various vases off of Popeye’s head with a cane. Finally, Bluto spots Popeye’s spinach can upon a table, and decides to fully liven up the action, tossing it willingly to the sailor. Popeye and Bluto now really have at it, rolling through the living room like a steamroller, smashing furniture and tableware in their wake, and sweeping up Olive into their fight cloud as well. The fight continues through the final shot, as Olive, Bluto, and Popeye each pop out of the fight cloud momentarily, to take portions of the final song phrase: “Can’t you see”, “It’s the natural” “Thing to do!”

The donut, however, flips onto her nose, a ringer in any horseshoe match. Popeye gets his finger stuck in a teacup handle, and when he pulls it loose, jabs Bluto, who spits out the cream from a filled cruller into Olive’s face. Bluto attempts an apology with unnaturally-long words, but Olive politely dismisses the incident, changing the subject to “Shall we converse a bit?” Bluto remarks that he’s heard that conversing is coming back, and Popeye claims it breaks up the monopoly of not talking. “Who will open?”, Olive asks. In the manner of a poker game, Bluto responds, “I’ll pass.” “They say language is used more for talkin’ than any other”, begins Popeye. Time passes slowly – so slow, the minute hand of the clock has to develop arms to drag the hour hand past the next hour mark. All of our participants still sit where they were, entirely listless, drooping, and without a thing to say. Popeye finally begins to chuckle to himself, then to laugh heartily, muttering how silly this gentleman stuff is. Bluto begins to join in the laughter, and soon Olive is tittering. She pulls out her etiquette book again, and remarks between giggles, “Etiquette – what a joke!”, tearing the book in two. Popeye continues to belly laugh, and in his reactive movements, accidentally lands a light blow to Bluto’s jaw. Bluto returns the favor, with a laughing jab at Popeye’s face. Soon, the two are jutting out their chins to take the inevitaable next blow, and Bluto finally smacks Popeye with a good one, sailing him across the room and through a framed picture, from which his feet appear, twitching in a manner resembling a Russian dancer. Soon, the boys are tossing furniture at each other. Bluto spins Popeye around on a piano stool, while Popeye delivers a mule kick to Bluto’s rear. Olive begins happily playing a flute in appreciation of the action. Popeye dodges Bluto’s throws of crockery, ducking in and out of a chest of drawers, while Olive cracks various vases off of Popeye’s head with a cane. Finally, Bluto spots Popeye’s spinach can upon a table, and decides to fully liven up the action, tossing it willingly to the sailor. Popeye and Bluto now really have at it, rolling through the living room like a steamroller, smashing furniture and tableware in their wake, and sweeping up Olive into their fight cloud as well. The fight continues through the final shot, as Olive, Bluto, and Popeye each pop out of the fight cloud momentarily, to take portions of the final song phrase: “Can’t you see”, “It’s the natural” “Thing to do!”

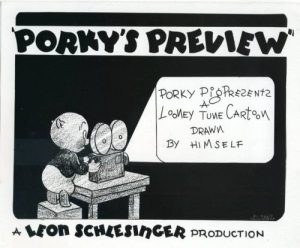

Porky’s Preview (Warner, Looney Tunes (Porky Pig), 4/19/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir,) – Borrowing a leaf from “Mutt and Jeff On Strike”, Porky Pig decides to self-produce his own cartoon. He dolls-up a barn as a legitimate theater, complete with ticket booth, ticket taker (a kangaroo who drops the torn ticket stubs into his pouch), and usher (a black-accented firefly who uses his tail light as a flashlight to guide customers to their seats). A hen buys tickets for one adult and three children – carrying against her tail a nest of three unhatched eggs. A skunk can’t pay the five-cent price of admission, having only “one scent – get it?” The skunk nevertheless sneaks in an exit door, just as the show commences. Porky steps out upon a makeshift stage, explaining that he drew this cartoon all by himself. “But s-s-shucks, it wasn’t hard b-b-because, I’m an artist.” The house lights dim, and the curtain opens on a projection screen, displaying a blank white title card, on which appear the words, Porky Pig Presents, and a terribly-doodled self-image of Porky’s face, with an arrow pointing at it with the label, “Me”. Next appear the words. “Porky Pig’s Funny Pictures, drawn by Porky Pig (artist) (7 years old) 2nd grade, Draft No. 6 7/8 (funny)” All characters in the film are depicted as black and white thin-line stick figures. First up is a circus parade, with various outline animals, including a line of elephants, with one much smaller than the others suspended between trunk and tail of the elephants behind and ahead of him, his feet coming nowhere close to touching the ground. Following the parade is a street sweeper to clean up the mess. Next act depicts a choo-choo train, with extendable wheels so that it can travel over successive doodled hills, maintaining a level cab while the wheels rise and fall with the terrain of each hill. The scrolling background runs out, reaching a point marked “End”, but the train wheels keep bobbing up and down in repeated animation, just as if the background never disappeared. Act 3 is “Soldiers (marchin)”. A gag is repeated from “The Penguin Parade”, where soldiers approach each other from both sides of the screen, and match each other’s cadence with their feet, allowing them to walk vertically up the screen upon each other’s feet. Instead of eventually falling as in the original cartoon, the soldiers simply reverse their actions in double-time to return to the ground.

Porky’s Preview (Warner, Looney Tunes (Porky Pig), 4/19/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir,) – Borrowing a leaf from “Mutt and Jeff On Strike”, Porky Pig decides to self-produce his own cartoon. He dolls-up a barn as a legitimate theater, complete with ticket booth, ticket taker (a kangaroo who drops the torn ticket stubs into his pouch), and usher (a black-accented firefly who uses his tail light as a flashlight to guide customers to their seats). A hen buys tickets for one adult and three children – carrying against her tail a nest of three unhatched eggs. A skunk can’t pay the five-cent price of admission, having only “one scent – get it?” The skunk nevertheless sneaks in an exit door, just as the show commences. Porky steps out upon a makeshift stage, explaining that he drew this cartoon all by himself. “But s-s-shucks, it wasn’t hard b-b-because, I’m an artist.” The house lights dim, and the curtain opens on a projection screen, displaying a blank white title card, on which appear the words, Porky Pig Presents, and a terribly-doodled self-image of Porky’s face, with an arrow pointing at it with the label, “Me”. Next appear the words. “Porky Pig’s Funny Pictures, drawn by Porky Pig (artist) (7 years old) 2nd grade, Draft No. 6 7/8 (funny)” All characters in the film are depicted as black and white thin-line stick figures. First up is a circus parade, with various outline animals, including a line of elephants, with one much smaller than the others suspended between trunk and tail of the elephants behind and ahead of him, his feet coming nowhere close to touching the ground. Following the parade is a street sweeper to clean up the mess. Next act depicts a choo-choo train, with extendable wheels so that it can travel over successive doodled hills, maintaining a level cab while the wheels rise and fall with the terrain of each hill. The scrolling background runs out, reaching a point marked “End”, but the train wheels keep bobbing up and down in repeated animation, just as if the background never disappeared. Act 3 is “Soldiers (marchin)”. A gag is repeated from “The Penguin Parade”, where soldiers approach each other from both sides of the screen, and match each other’s cadence with their feet, allowing them to walk vertically up the screen upon each other’s feet. Instead of eventually falling as in the original cartoon, the soldiers simply reverse their actions in double-time to return to the ground.

Act 4 is a horse race. The field of horses passes in a dash for the finish line, but a few moments later is followed by a lazy nag, just plodding along, with an arrow and accompanying words slowly following it on the screen, reading “Crosby’s horse” (a recurring joke of Warner cartoons about Bing Crosby’s personal stable of racing horses, always coming in out of the money). Act 6 presents a variety of dances. A stick figure hula dancer has her grass skirt fall, revealing nothing but a merger of lines where her legs attach to her stick torso. However, she is mortified with embarrassment, uttering words that appear in visible form on the screen, “Oh, oh, oh!”, as she picks up her grass skirt and quickly disappears from view. A Mexican dancer repeatedly misses his opening music cue, causing his drawing to be crossed-out by a wiggly pencil line, and his animation to restart again. When he finally gets his opening cue right, his dance is considered so poor by Porky that he crosses the character out again anyway. Finally, a ballet troupe performs (with another in the line out of size when matched with the others, the same as the elephant in Act 1). A solo dancer performs a wide-legged split, then rises with her legs double their original length and her torso all scrunched up above them, to awkwardly walk off stage. A finale is provided by a caricature of Al Jolson’s face atop a stick body, singing “September In the Rain”, while oversized raindrops from a doodled cloud periodically bounce off his head. An iris out appears, with no frame of the closing view drawn as a perfect circle. The house lights go up, as Porky once again takes the stage. “Well, f-f-folks, how did you like my picture?” The audience has apparently stampeded for the exits, taking most of the outer wall of the barn along with them, and the only pair of hands left applauding Porky are those of the freeloading skunk – leading one to ponder which smelled worse – the skunk, or the picture?

Act 4 is a horse race. The field of horses passes in a dash for the finish line, but a few moments later is followed by a lazy nag, just plodding along, with an arrow and accompanying words slowly following it on the screen, reading “Crosby’s horse” (a recurring joke of Warner cartoons about Bing Crosby’s personal stable of racing horses, always coming in out of the money). Act 6 presents a variety of dances. A stick figure hula dancer has her grass skirt fall, revealing nothing but a merger of lines where her legs attach to her stick torso. However, she is mortified with embarrassment, uttering words that appear in visible form on the screen, “Oh, oh, oh!”, as she picks up her grass skirt and quickly disappears from view. A Mexican dancer repeatedly misses his opening music cue, causing his drawing to be crossed-out by a wiggly pencil line, and his animation to restart again. When he finally gets his opening cue right, his dance is considered so poor by Porky that he crosses the character out again anyway. Finally, a ballet troupe performs (with another in the line out of size when matched with the others, the same as the elephant in Act 1). A solo dancer performs a wide-legged split, then rises with her legs double their original length and her torso all scrunched up above them, to awkwardly walk off stage. A finale is provided by a caricature of Al Jolson’s face atop a stick body, singing “September In the Rain”, while oversized raindrops from a doodled cloud periodically bounce off his head. An iris out appears, with no frame of the closing view drawn as a perfect circle. The house lights go up, as Porky once again takes the stage. “Well, f-f-folks, how did you like my picture?” The audience has apparently stampeded for the exits, taking most of the outer wall of the barn along with them, and the only pair of hands left applauding Porky are those of the freeloading skunk – leading one to ponder which smelled worse – the skunk, or the picture?

The Reluctant Dragon (Disney/RKO, 6/20/41) is one of the ultimate films about animation, half of its footage devoted to a live-action behind the scenes tour of the Walt Disney studio. Animated characters, however, get into the act tn two instances in the film. Humorist Robert Benchley visits the camera room, where cels of Donald Duck are being photographed, probably made especially for the feature, but in the same style and costume as Donald’s forthcoming appearance in “Old MacDonald Duck”. Benchley feigns not being able to figure out why each drawing is slightly different than the next, and why they don’t up and move. Suddenly, Donald, on the camera mount, turns his head to Benchley, and states “Gimme time. Gimme time.” Donals himself begins to explain to Benchley that his feet are in one position, then another, then another, as the scene progresses, and then, projected at full speed, he appears to be walking. Donald closes his brief cameo by singing a few bars of “Old MacDonald Had a Farm.” Benchley laughs, telling one of the staff that the duck cracks him up – though he doesn’t understand a word the duck says.

The Reluctant Dragon (Disney/RKO, 6/20/41) is one of the ultimate films about animation, half of its footage devoted to a live-action behind the scenes tour of the Walt Disney studio. Animated characters, however, get into the act tn two instances in the film. Humorist Robert Benchley visits the camera room, where cels of Donald Duck are being photographed, probably made especially for the feature, but in the same style and costume as Donald’s forthcoming appearance in “Old MacDonald Duck”. Benchley feigns not being able to figure out why each drawing is slightly different than the next, and why they don’t up and move. Suddenly, Donald, on the camera mount, turns his head to Benchley, and states “Gimme time. Gimme time.” Donals himself begins to explain to Benchley that his feet are in one position, then another, then another, as the scene progresses, and then, projected at full speed, he appears to be walking. Donald closes his brief cameo by singing a few bars of “Old MacDonald Had a Farm.” Benchley laughs, telling one of the staff that the duck cracks him up – though he doesn’t understand a word the duck says.

Also included in the same feature, interacting with the world beyond the animation screen, is Goofy, appearing in a full episode within the film which officially began his series of mock-instructional shorts, “How To Ride a Horse”. (A recent post on this website correctly noted that “Goofy’s Glider” was the first of such narrator-driven shorts, though not billed by the title of the book Goofy is reading, “How to Fly:” However, Goofy doesn’t have all that many opportunities in the first film to react directly to the narrator’s commands, which just as easily may be attributed by him to the book he is reading.) Here, Goofy is definitely aware that a narrator is following his every move, and is forced to respond at the narrator’s words in fashion intended to demonstrate his stated principles. He and the horse are entirely puzzled by the narrator’s confusing efforts to explain the wrong side for mounting a horse, which comes out sounding like the verse Danny Kaye years later would have to memorize in “The Court Jester” to determine which of two chalices contained poison – “The right side is wrong, so the left is right.” Goof and the horse begin to lose track entirely, and exchange wide-mouthed yawns that seem to make each of them sleepier and sleepier. “All right”, the narrator suddenly shouts in summing up, causing both onscreen characters to snap to attention, but carry out the mounting exactly the opposite way from which the narrator explained. Near the end of the short, Goof, riding in the saddle, takes the horse at full gallop straight toward a high fence, expecting to jump. The horse double-crosses him, slamming on the brakes as if stopping on a dime. Goof soars out of the saddle, over the top of the fence at full rein length, and is about to hit a large pool of water on the other side of the fence face-first, when the narrator commands, “STOP!” Goof freezes in mid-air, his face a mere inch from impact with the water surface. “We’ll go back and try that again”, declares the frustrated narrator. Goof gives a brief look to the camera and announcer that registers the thought, “Oh, no. Do we really have to?” The animation quickly shifts into reverse, as Goof snaps backwards into the saddle, and the horse’s gallop races in reverse gear. But Goof and the horse never get to repeat the stunt, as running backwards deprives the horse of accurate aim, causing him to gallop in reverse up the side of the tallest tree in the area. “Whoa. WHOA!” shouts the narrator, bringing the sequence to a close with the horse and Goofy astride him precariously balanced upon the thinnest topmost limbs of the tall tree, swaying in the breeze.

Also included in the same feature, interacting with the world beyond the animation screen, is Goofy, appearing in a full episode within the film which officially began his series of mock-instructional shorts, “How To Ride a Horse”. (A recent post on this website correctly noted that “Goofy’s Glider” was the first of such narrator-driven shorts, though not billed by the title of the book Goofy is reading, “How to Fly:” However, Goofy doesn’t have all that many opportunities in the first film to react directly to the narrator’s commands, which just as easily may be attributed by him to the book he is reading.) Here, Goofy is definitely aware that a narrator is following his every move, and is forced to respond at the narrator’s words in fashion intended to demonstrate his stated principles. He and the horse are entirely puzzled by the narrator’s confusing efforts to explain the wrong side for mounting a horse, which comes out sounding like the verse Danny Kaye years later would have to memorize in “The Court Jester” to determine which of two chalices contained poison – “The right side is wrong, so the left is right.” Goof and the horse begin to lose track entirely, and exchange wide-mouthed yawns that seem to make each of them sleepier and sleepier. “All right”, the narrator suddenly shouts in summing up, causing both onscreen characters to snap to attention, but carry out the mounting exactly the opposite way from which the narrator explained. Near the end of the short, Goof, riding in the saddle, takes the horse at full gallop straight toward a high fence, expecting to jump. The horse double-crosses him, slamming on the brakes as if stopping on a dime. Goof soars out of the saddle, over the top of the fence at full rein length, and is about to hit a large pool of water on the other side of the fence face-first, when the narrator commands, “STOP!” Goof freezes in mid-air, his face a mere inch from impact with the water surface. “We’ll go back and try that again”, declares the frustrated narrator. Goof gives a brief look to the camera and announcer that registers the thought, “Oh, no. Do we really have to?” The animation quickly shifts into reverse, as Goof snaps backwards into the saddle, and the horse’s gallop races in reverse gear. But Goof and the horse never get to repeat the stunt, as running backwards deprives the horse of accurate aim, causing him to gallop in reverse up the side of the tallest tree in the area. “Whoa. WHOA!” shouts the narrator, bringing the sequence to a close with the horse and Goofy astride him precariously balanced upon the thinnest topmost limbs of the tall tree, swaying in the breeze.

As these kinds of gags ultimately became stock-in-trade for the “How To” series, I won’t be dwelling greatly upon the theme and variation upon same that frequently appeared in later episodes, and we’ll only touch upon the series again in subsequent installments from time to time. A few variants, however, deserve brief honorable mention. In “The Art of Self-Defense” (12/26/41 – Jack Kinney, dir.), the Goof, training to be a prize-fighter, is introduced to the fine art of shadow-boxing. A call of “Hey, you” from the narrator elicits an initial facial reaction from Goofy. “Not you, the other fella”, clarifies the narrator under his breath, revealing he was addressing the shadow, who leaps off the wall, and shakes hands with his opponent (delivering a vice-lock handshake that crumples Goofy’s right hand). The two mix it up, the shadow delivering some telling blows to Goofy, at one point resulting in Goofy’s jaw being on a direct collision course with the shadow’s fist. The narrator again calls for a stop to the action, freezing the shadow glove an inch away from impact, so that the narrator can discuss the finer points of the swing with the audience, and point out how the blow is calculated to deliver maximum force right on the button. While all this is occurring, poor Goofy’s eyes can only fixate upon the shadow glove ready to do its worst to his facial features, and, with his own body frozen in air and unable to put up any kind of defensive pose, the poor dog can only gulp his salica down his throat and emit bullets of nervous perspiration in anticipation of what’s coming. The blow indeed turns out to be everything everyone was waiting for.

As these kinds of gags ultimately became stock-in-trade for the “How To” series, I won’t be dwelling greatly upon the theme and variation upon same that frequently appeared in later episodes, and we’ll only touch upon the series again in subsequent installments from time to time. A few variants, however, deserve brief honorable mention. In “The Art of Self-Defense” (12/26/41 – Jack Kinney, dir.), the Goof, training to be a prize-fighter, is introduced to the fine art of shadow-boxing. A call of “Hey, you” from the narrator elicits an initial facial reaction from Goofy. “Not you, the other fella”, clarifies the narrator under his breath, revealing he was addressing the shadow, who leaps off the wall, and shakes hands with his opponent (delivering a vice-lock handshake that crumples Goofy’s right hand). The two mix it up, the shadow delivering some telling blows to Goofy, at one point resulting in Goofy’s jaw being on a direct collision course with the shadow’s fist. The narrator again calls for a stop to the action, freezing the shadow glove an inch away from impact, so that the narrator can discuss the finer points of the swing with the audience, and point out how the blow is calculated to deliver maximum force right on the button. While all this is occurring, poor Goofy’s eyes can only fixate upon the shadow glove ready to do its worst to his facial features, and, with his own body frozen in air and unable to put up any kind of defensive pose, the poor dog can only gulp his salica down his throat and emit bullets of nervous perspiration in anticipation of what’s coming. The blow indeed turns out to be everything everyone was waiting for.

Watch the Goofy Short: CLICK HERE

The Heckling Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 8/5/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – Another cartoon first from Avery, though derivative of a Clampett gag for the Dodo Bird in “Porky in Wackyland”. Bugs Bunny rides the Warner shield into the opening studio credits for the first time, munching his carrot, then pausing to glance at the audience, realizing he is being watched. He reaches up to pull at a curtain ring, bringing down the “Merrie Melodies” sign between himself and the audience for a little privacy. (The curtain pull in this first effort is much more slow and deliberate than that we became used to in later films of the 1940’s and 1950’s.) A basically plotless series of chase and outwit gags follow, as Bugs faces off against Willoughby the hound, a slow-witted, semi-recurring character first seen in modified form in 1940’s “Of Fox and Hounds”. The sequence remembered from this short has Willoughby attempting to fiollow Bugs into a rabbit hole, by digging furiously to widen and deepen the hole. However, Willoughby fails to notice that the hole is located quite close to the edge of a cliff, the bottom of which tapers off considerably, so that as Willoughby burrows straight down, he comes out of the earthen bottom of the cliff ledge, facing a sheer drop below. Willoughby briefly defies gravity, leaping back up through the hole and scrambling back atop the ledge surface. He chances a quick look down through the hole, revealing a view of terrain about a mile below the cliff. “Did you see what nearly happened to me?”, Willoughby asks the audience, still shaken and perspiring nervously. “I gotta be more careful”, he continues, reversing direction to walk away from the hole – in the wrong direction, and right off the edge of the cliff. Willoughby plunges down and out of camera view, as Bugs reappears from nowhere, looking over the cliff side, and remarking calmly. “Too bad. But the jerk had it comin’ to him. He shoulda watched his step.” Bugs turns away from the cliff, but performs a misstep as foolish as Willoughby, entering the same rabbit hole Willoughby just tunneled through, and falling through its open bottom, into the same open ether as Willoughby is now falling through. Bugs somehow catches up with Willoughby in mid-fall, and the two hysterically cling to each other and scream for a good forty seconds or so, as their speed increases, the ground spirals toward them faster and faster, and mutual doom seems impending. Just as the scene looks utterly hopeless, each of the characters separate from one another, pull upwards on their own feet with their arms, and the sound of brakes is heard, as each slows to a comfortable speed, and stops on a dime on the ground surface below, entirely without injury. “Nyahh, fooled ya, didn’t we?” jeers Bugs at the audience. “Yeah”, adds Willoughby, for an abrupt, post-production fade out. The fade was one of many instances where Warner removed an unwanted ending by a quick film-snip before general release, and no original director’s cut of the missing last shot has surfaced. Legend has it that Willoughby turned to make an exit, somehow again plunging off a second ledge into another fall. Some remark was made by Bugs to the effect of “Here we go again”, but which is supposed to have been interpreted by Leon Schlesinger as parallel to a dirty joke circulating at the time, then follows Willoughby to join him in the second fall. The disagreement over the ending is legendarily reputed to have led to Avery’s firing from the studio, and his equally-legendary move to MGM, where perhaps the best work of his career was about to begin.

The Heckling Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 8/5/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – Another cartoon first from Avery, though derivative of a Clampett gag for the Dodo Bird in “Porky in Wackyland”. Bugs Bunny rides the Warner shield into the opening studio credits for the first time, munching his carrot, then pausing to glance at the audience, realizing he is being watched. He reaches up to pull at a curtain ring, bringing down the “Merrie Melodies” sign between himself and the audience for a little privacy. (The curtain pull in this first effort is much more slow and deliberate than that we became used to in later films of the 1940’s and 1950’s.) A basically plotless series of chase and outwit gags follow, as Bugs faces off against Willoughby the hound, a slow-witted, semi-recurring character first seen in modified form in 1940’s “Of Fox and Hounds”. The sequence remembered from this short has Willoughby attempting to fiollow Bugs into a rabbit hole, by digging furiously to widen and deepen the hole. However, Willoughby fails to notice that the hole is located quite close to the edge of a cliff, the bottom of which tapers off considerably, so that as Willoughby burrows straight down, he comes out of the earthen bottom of the cliff ledge, facing a sheer drop below. Willoughby briefly defies gravity, leaping back up through the hole and scrambling back atop the ledge surface. He chances a quick look down through the hole, revealing a view of terrain about a mile below the cliff. “Did you see what nearly happened to me?”, Willoughby asks the audience, still shaken and perspiring nervously. “I gotta be more careful”, he continues, reversing direction to walk away from the hole – in the wrong direction, and right off the edge of the cliff. Willoughby plunges down and out of camera view, as Bugs reappears from nowhere, looking over the cliff side, and remarking calmly. “Too bad. But the jerk had it comin’ to him. He shoulda watched his step.” Bugs turns away from the cliff, but performs a misstep as foolish as Willoughby, entering the same rabbit hole Willoughby just tunneled through, and falling through its open bottom, into the same open ether as Willoughby is now falling through. Bugs somehow catches up with Willoughby in mid-fall, and the two hysterically cling to each other and scream for a good forty seconds or so, as their speed increases, the ground spirals toward them faster and faster, and mutual doom seems impending. Just as the scene looks utterly hopeless, each of the characters separate from one another, pull upwards on their own feet with their arms, and the sound of brakes is heard, as each slows to a comfortable speed, and stops on a dime on the ground surface below, entirely without injury. “Nyahh, fooled ya, didn’t we?” jeers Bugs at the audience. “Yeah”, adds Willoughby, for an abrupt, post-production fade out. The fade was one of many instances where Warner removed an unwanted ending by a quick film-snip before general release, and no original director’s cut of the missing last shot has surfaced. Legend has it that Willoughby turned to make an exit, somehow again plunging off a second ledge into another fall. Some remark was made by Bugs to the effect of “Here we go again”, but which is supposed to have been interpreted by Leon Schlesinger as parallel to a dirty joke circulating at the time, then follows Willoughby to join him in the second fall. The disagreement over the ending is legendarily reputed to have led to Avery’s firing from the studio, and his equally-legendary move to MGM, where perhaps the best work of his career was about to begin.

Woody Woodpecker (Lantz/Universal, 7/7/41 – Walter Lantz, dir.) – Woody’s official debut as a stand-alone star. Everybody in the forest thinks Woody, in his original garish design and color scheme, is crazy – pixilated – has some screws loose. Woody seems well aware of such popular opinion, introducing himself by performing what became his first signature theme song “Knock on Wood (Everybody Thinks I’m Crazy)” (a ditty which would still see reuse as late as 1954’s “Hot Rod Huckster”). Woody tries to stand up to his detractors, telling one bird, “Aw, go lay an egg”, only to have one dropped on his face. Another causes him to fall and smack his head, causing Woody to see multiple phantom images of himself. Woody thinks he’s being ganged up on, and wages battle with his own images. Finally, he tries to convince a bluebird and a squirrel he’s okay, by demonstrating how neatly he can peck a tree into a totem pole. They respond by challenging him, “If you’re so smart, let’s see whatcha can do to that tree.” They point him to a fake tree made of sculpted stone, part of a park statue. Woody smacks headfirst into the marble monument, producing an ear-splitting ringing in his head, then his entire bofy. He begins to hear voices repeating the taunts of his woodland cronies, and insisting that he should get his head examined. Woody (voiced by Mel Blanc) pulls a Porky Pig line, stating to the audience, “Maybe I’d better see a phychia – [hic] – a phychia – [hic] – I’ll go see a doctor.”

Woody Woodpecker (Lantz/Universal, 7/7/41 – Walter Lantz, dir.) – Woody’s official debut as a stand-alone star. Everybody in the forest thinks Woody, in his original garish design and color scheme, is crazy – pixilated – has some screws loose. Woody seems well aware of such popular opinion, introducing himself by performing what became his first signature theme song “Knock on Wood (Everybody Thinks I’m Crazy)” (a ditty which would still see reuse as late as 1954’s “Hot Rod Huckster”). Woody tries to stand up to his detractors, telling one bird, “Aw, go lay an egg”, only to have one dropped on his face. Another causes him to fall and smack his head, causing Woody to see multiple phantom images of himself. Woody thinks he’s being ganged up on, and wages battle with his own images. Finally, he tries to convince a bluebird and a squirrel he’s okay, by demonstrating how neatly he can peck a tree into a totem pole. They respond by challenging him, “If you’re so smart, let’s see whatcha can do to that tree.” They point him to a fake tree made of sculpted stone, part of a park statue. Woody smacks headfirst into the marble monument, producing an ear-splitting ringing in his head, then his entire bofy. He begins to hear voices repeating the taunts of his woodland cronies, and insisting that he should get his head examined. Woody (voiced by Mel Blanc) pulls a Porky Pig line, stating to the audience, “Maybe I’d better see a phychia – [hic] – a phychia – [hic] – I’ll go see a doctor.”

Woody shows up at the door of the office of Dr. Horace N. Buggy, whose sign boasts of his degrees: “A. E. I. O. U. and sometimes Y”, and also states, “Greetings Gate, Let’s Operate. Office Hours 10:52 to 10:53.” Horace, a fox, is a piece of work himself. When Woody rings a bell for him, the Doc rises from a bed in an adjoining room, then bundles up as if braving a storm to make a house call – just to travel two feet through a doorway into the main office. He performs a sanitary scrub in water of his hands up to his elbows, informing the audience that he saw this done in the movies. He offers one hand to Woody for a handshake, but his head elevates like an automobile jack when his hand is shaken. Woody and the Doc size each other up eye-to-eye like two fighting roosters, then for no good reason break into a rhythmic conga, followed by an ice-skating routine on the carpet. Horace admits to the audience “Any similarity between me and a doctor is purely coincidental.” Woody realizes what he s up against, and remarks, “I think this guy’s balmy.” Horace finally begins examination of Woody, giving him a series of confusing rapid-fire verbal commands: “Sit down. Stand up. Bend over. Straighten up. Open your mouth. Close your mouth. Stick out your tongue. Say ‘Ahhh’. Rub your head. Pat your foot.” Woody continues to perform these moves repeatedly, looking utterly like a madman. After a moment, the Doc calmly remarks, “Habit forming, isn’t it?” More pointless tests follow, including an eye examination. “Can’t see a thing, Doc”, says Woody repeatedly, for an obvious reason. “Well open your eyes!”, screams the Doctor. Woody’s eyelids finally rise. “I can see! Yeah, I can see! Doc, your wonderful”, shouts Woody. With no further prompting, Woody goes berserk, riding a windowshade up and down, then the carriage of a typewriter, darting in and out of desk drawers, swimming in a plush shag carpet, and scooping up the doctor in a wheelchair for a buggy ride. The wheelchair collides with a desk, pinning the doctor in his seat, but throwing Woody straight toward the closed exit door and right through it. Our camera angle changes to a theater-eye view of the screen, as Woody smashes through the door, landing in the first-row seats of the audience. The Doc pops his head through the hole in the door, advising the audience of his diagnosis. “Dinna mind him, folks. He’s crazy – but I’m all right. Or am I?” The doctor suddenly crosses his eyes, honks his own nose, and breaks into his own series of berserk fits. Our camera angle reverses, and we now focus on Woody, comfortably seated between two people in the theater front row. Woody now becomes a critic of his own cartoon, sharing his views to the unappreciative patrons on each side of him. “That doctor sure is a card, isn’t he? But I don’t think he’s near as funny as the Woodpecker. Do you think so, mister, huh? I like cartoons. Don’t you like cartoons?” One of the irritated theater patrons responds by grabbing Woody’s seat cushion and raising it, pinning Woody into a trap in the theater seat. “Help! Get me outta here!” shouts the struggling Woody, as the other theater-goers smile in satisfaction, for the fade out.

Woody shows up at the door of the office of Dr. Horace N. Buggy, whose sign boasts of his degrees: “A. E. I. O. U. and sometimes Y”, and also states, “Greetings Gate, Let’s Operate. Office Hours 10:52 to 10:53.” Horace, a fox, is a piece of work himself. When Woody rings a bell for him, the Doc rises from a bed in an adjoining room, then bundles up as if braving a storm to make a house call – just to travel two feet through a doorway into the main office. He performs a sanitary scrub in water of his hands up to his elbows, informing the audience that he saw this done in the movies. He offers one hand to Woody for a handshake, but his head elevates like an automobile jack when his hand is shaken. Woody and the Doc size each other up eye-to-eye like two fighting roosters, then for no good reason break into a rhythmic conga, followed by an ice-skating routine on the carpet. Horace admits to the audience “Any similarity between me and a doctor is purely coincidental.” Woody realizes what he s up against, and remarks, “I think this guy’s balmy.” Horace finally begins examination of Woody, giving him a series of confusing rapid-fire verbal commands: “Sit down. Stand up. Bend over. Straighten up. Open your mouth. Close your mouth. Stick out your tongue. Say ‘Ahhh’. Rub your head. Pat your foot.” Woody continues to perform these moves repeatedly, looking utterly like a madman. After a moment, the Doc calmly remarks, “Habit forming, isn’t it?” More pointless tests follow, including an eye examination. “Can’t see a thing, Doc”, says Woody repeatedly, for an obvious reason. “Well open your eyes!”, screams the Doctor. Woody’s eyelids finally rise. “I can see! Yeah, I can see! Doc, your wonderful”, shouts Woody. With no further prompting, Woody goes berserk, riding a windowshade up and down, then the carriage of a typewriter, darting in and out of desk drawers, swimming in a plush shag carpet, and scooping up the doctor in a wheelchair for a buggy ride. The wheelchair collides with a desk, pinning the doctor in his seat, but throwing Woody straight toward the closed exit door and right through it. Our camera angle changes to a theater-eye view of the screen, as Woody smashes through the door, landing in the first-row seats of the audience. The Doc pops his head through the hole in the door, advising the audience of his diagnosis. “Dinna mind him, folks. He’s crazy – but I’m all right. Or am I?” The doctor suddenly crosses his eyes, honks his own nose, and breaks into his own series of berserk fits. Our camera angle reverses, and we now focus on Woody, comfortably seated between two people in the theater front row. Woody now becomes a critic of his own cartoon, sharing his views to the unappreciative patrons on each side of him. “That doctor sure is a card, isn’t he? But I don’t think he’s near as funny as the Woodpecker. Do you think so, mister, huh? I like cartoons. Don’t you like cartoons?” One of the irritated theater patrons responds by grabbing Woody’s seat cushion and raising it, pinning Woody into a trap in the theater seat. “Help! Get me outta here!” shouts the struggling Woody, as the other theater-goers smile in satisfaction, for the fade out.

Aviation Vacation (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 8/2/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – While Avery had already received his walking papers, several of the prolific director’s projects were still in the pipeline. This one slipped through with Avery’s name still on the credits, though Schlesinger would quickly thereafter begin a studio practice of altering credits to remove the names of fired personnel. Perhaps, as the titles were integrated into the first shot of animation here, Schlesinger thought it too costly to reshoot the scene just to remove Avery’s name. The film itself is perhaps one of the most lackluster of Avery’s travelogue spoofs, with several gags that feel like retreads of material from prior films, including a “fog is lifting” ending reveal that is nearly identical to the ending of “Land Of the Midnight Fun”, revealing the plane circling the field, tethered to an amusement park airplane ride.

Aviation Vacation (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 8/2/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – While Avery had already received his walking papers, several of the prolific director’s projects were still in the pipeline. This one slipped through with Avery’s name still on the credits, though Schlesinger would quickly thereafter begin a studio practice of altering credits to remove the names of fired personnel. Perhaps, as the titles were integrated into the first shot of animation here, Schlesinger thought it too costly to reshoot the scene just to remove Avery’s name. The film itself is perhaps one of the most lackluster of Avery’s travelogue spoofs, with several gags that feel like retreads of material from prior films, including a “fog is lifting” ending reveal that is nearly identical to the ending of “Land Of the Midnight Fun”, revealing the plane circling the field, tethered to an amusement park airplane ride.

The “hair-in-the-gate” gag

See the film if you CLICK HERE.

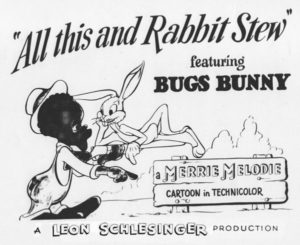

All This and Rabbit Stew (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 9/13/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – The final Bugs theatrical directed by Avery, though his name had by now been removed from the credits by Schlesinger. This one made the “Censored 11″ for pitting Bugs against a “Sambo”-style black hunter with protruding lips and a Stepin Fetchit demeanor and voice, who lazily shuffles along, mumbly-singing, “I’m gonna catch me a rabbit.” It is another essentially plotless series of hunter spot-gags, with a few racial jokes thrown in. A funny shot has Bugs and the hunter both escaping a bear’s cave (the bear turns up hiding in the same tree stump as them, as frightened as they are), then Bugs and the hunter further escaping the bear, mopping their brows and trudging away in exhausted fashion. But Bugs’ feet aren’t even touching the ground, as his every step places his feet upon the toes of the oversized feet of the black hunter walking behind him. Another sequence from this film would be rescued for reuse by both Bob Clampett and Friz Freleng, in later productions such as “The Big Snooze”, “Foxy By Proxy”. and “Person To Bunny”, with Bugs entering a hollow log, through which the hinter pursues him. Bugs emerges from the log’s other end first, and pushes the log so that one end extends out over the edge of a cliff. The hunter emerges, walking on air, then stops, transforming into the image of a lollipop with a wrapper reading “Sucker”. He quickly darts back into the log, defying gravity. As the hunter scrambles for the opposite exit, Bugs quickly spins the log around, so that the opposite end now extends over the cliff. The same exit by the hunter is repeated, as he now thinks both ends of the log lead to the same cliff. Darting back once again inside the log, the hunter is now more cautious, reaching only his hand out of one end of the log, to find and touch solid ground outside. The footsteps of the hinter begin once again, but Bugs is quicker, again giving the log a spin. For the third time, the hunter emerges into thin air, and this time helplessly plummets. Avery also exhibits one of his first unique shock-takes, having Bugs react to the surprise return of the hunter in a pull back that simultaneously explodes his head and limbs apart from his torso. But Bugs still maintains the upper hand, in a stereotypical gag playing on the notion that all blacks are addicted to gambling. Bugs rattles a pair of objects in his hand, immediately attracting the attention of Sambo. It couldn’t be a pair of – – yes, it is. Dice. Sambo immediately leads Bugs behind a bush, and the betting is on, as both rattle them bones to make their respective point. Sambo has the final roll, praying, “Dice, don’t fail me now”. He rolls, shouting “Wham” – then, a silence. “Too bad, Doc”, says Bugs. Bugs emerges from the bush a moment later, fully outfitted with Sambo’s clothes and shotgun – his winnings from the game. He looks back, as the camera pans back to the bush, where a naked Sambo stands, covered only where it counts by a large fig leaf. “Well, call me Adam”, he remarks to the audience. An iris out closes on the scene, but Bugs once again proves his conscious existence in a plane somewhere between screen and audience, having already gotten out front on the stage to escape the iris out. He enters our view from stage right just as the iris circle is about to shut, and reaches an arm into the circle, back to the cartoon world. A moment later, his arm pills out of the hole, carrying with it to the stage Sambo’s fig leaf, which Bugs proudly displays to the audience as the iris closes completely, signifying the final bounty of Bugs’ winnings in total defeat of his adversary, as the light fades out.

All This and Rabbit Stew (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 9/13/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – The final Bugs theatrical directed by Avery, though his name had by now been removed from the credits by Schlesinger. This one made the “Censored 11″ for pitting Bugs against a “Sambo”-style black hunter with protruding lips and a Stepin Fetchit demeanor and voice, who lazily shuffles along, mumbly-singing, “I’m gonna catch me a rabbit.” It is another essentially plotless series of hunter spot-gags, with a few racial jokes thrown in. A funny shot has Bugs and the hunter both escaping a bear’s cave (the bear turns up hiding in the same tree stump as them, as frightened as they are), then Bugs and the hunter further escaping the bear, mopping their brows and trudging away in exhausted fashion. But Bugs’ feet aren’t even touching the ground, as his every step places his feet upon the toes of the oversized feet of the black hunter walking behind him. Another sequence from this film would be rescued for reuse by both Bob Clampett and Friz Freleng, in later productions such as “The Big Snooze”, “Foxy By Proxy”. and “Person To Bunny”, with Bugs entering a hollow log, through which the hinter pursues him. Bugs emerges from the log’s other end first, and pushes the log so that one end extends out over the edge of a cliff. The hunter emerges, walking on air, then stops, transforming into the image of a lollipop with a wrapper reading “Sucker”. He quickly darts back into the log, defying gravity. As the hunter scrambles for the opposite exit, Bugs quickly spins the log around, so that the opposite end now extends over the cliff. The same exit by the hunter is repeated, as he now thinks both ends of the log lead to the same cliff. Darting back once again inside the log, the hunter is now more cautious, reaching only his hand out of one end of the log, to find and touch solid ground outside. The footsteps of the hinter begin once again, but Bugs is quicker, again giving the log a spin. For the third time, the hunter emerges into thin air, and this time helplessly plummets. Avery also exhibits one of his first unique shock-takes, having Bugs react to the surprise return of the hunter in a pull back that simultaneously explodes his head and limbs apart from his torso. But Bugs still maintains the upper hand, in a stereotypical gag playing on the notion that all blacks are addicted to gambling. Bugs rattles a pair of objects in his hand, immediately attracting the attention of Sambo. It couldn’t be a pair of – – yes, it is. Dice. Sambo immediately leads Bugs behind a bush, and the betting is on, as both rattle them bones to make their respective point. Sambo has the final roll, praying, “Dice, don’t fail me now”. He rolls, shouting “Wham” – then, a silence. “Too bad, Doc”, says Bugs. Bugs emerges from the bush a moment later, fully outfitted with Sambo’s clothes and shotgun – his winnings from the game. He looks back, as the camera pans back to the bush, where a naked Sambo stands, covered only where it counts by a large fig leaf. “Well, call me Adam”, he remarks to the audience. An iris out closes on the scene, but Bugs once again proves his conscious existence in a plane somewhere between screen and audience, having already gotten out front on the stage to escape the iris out. He enters our view from stage right just as the iris circle is about to shut, and reaches an arm into the circle, back to the cartoon world. A moment later, his arm pills out of the hole, carrying with it to the stage Sambo’s fig leaf, which Bugs proudly displays to the audience as the iris closes completely, signifying the final bounty of Bugs’ winnings in total defeat of his adversary, as the light fades out.

NEXT: Things to do in ‘42.