Part three in our series of self-referential animated films, highlighting the medium and savvy characters with knowledge of their pen-and-paper world. We pick up in 1933, covering developments into the next few years, with action from Disney, Fleischer, and Warner Brothers,

Ride Him, Bosko (Harman-Ising, Looney Tunes, 1/16/33 – Hugh Harman, dir.) – A typical tale of the old West begins in the town of Red Gulch – where men are men (nine times out of ten). Receptions for those that pass the saloon are befitting of such a community. One gets conked with a whiskey bottle. Another (a dachshund) has his midriff shot out chunk by chunk by a hail of bullets. Cowboy Bosko approaches the saloon swinging doors, cheerily greeting those inside, “Howdy, fellas.” Machine gun fire riddles his hat with bullet holes, after which the playful inhabitants of the establishment cheerily respond back, “Hi, Bosko.” Goopy Geer cameos as piano player, downing a house specialty from a tall glass atop the piano – which burns his whole wardrobe to a crisp. Goopy must be that tenth man who isn’t quite a man, as he effeminately shouts, “Whoop”, and sidles off in embarrassment at his partial nudity. Bosko takes over piano duties, with some dancers dancing in recycled animation from “Moonlight For Two”. In a poker player’s hand, two kings, a queen, and a Joker join in vocalizing with Bosko’s tune, until a bullet puts the singing Joker out of commission. Meanwhile, outside in the badlands, the Deadwood stage (free-wheeling) hurtles through the night, carrying a single passenger (Honey) and her trunk. The stage is beset by bandits, who emerge from behind a rock at the side of the road, their leader raising two six-guns as a sign for the coach to stop. But the coach entirely ignores him, passing so fast, the bandit and his guns are sent into a spiraling spin. The bandits are forced to re-mount and give chase. One shot knocks Honey’s trunk off the coach roof, and her wardrobe emerges, making a quick exit for the hills to escape the gunfire. As the coach hits a rock, the stage driver is ejected from his set, sliding down a cactus full of thorny needles, then hopping onto the back of a cattle skeleton, which comes to life and gallops away with the driver. A possible continuity error occurs, as a stranger, rather than the driver, enters the saloon in town to alert Bosko that the stage is being held up. (Where did thus guy learn of these events, since we’ve never seen him before?) In another continuity error, Bosko races outside for his horse, attempting to leap into the saddle, but lands on a hitching post that wasn’t there when Bosko arrived in town, riding the post around a few times in circles before being thrown to the ground. Boski finally gets into the saddle, and takes off after the bandits. In continuity error number three, Bosko’s hat disappears from his head, as the camera pulls back from a panning shot of Bosko galloping along on his horse, to reveal he is on a drawing board, surrounded by the real-life Hugh Harman (there is some dispute here, as Leonard Maltin’s “Of Mice and Magic” claims it is animator Walker Harman), Rudolf Ising, and Norman Blackburn. Rudolf asks the others, “Say, how’s Bosko going to save the girl?” “I don’t know”, shrugs Blackburn. “Well, we’ve gotta do something”, responds Ising. “Let’s go home”, suggests Harman. “Good idea”, concludes Ising, as everyone reaches for their hats and departs, while Bosko and his mount slow to a stop on their board, with Bosko blinking to the audience as if to say, “What just happened?”

Ride Him, Bosko (Harman-Ising, Looney Tunes, 1/16/33 – Hugh Harman, dir.) – A typical tale of the old West begins in the town of Red Gulch – where men are men (nine times out of ten). Receptions for those that pass the saloon are befitting of such a community. One gets conked with a whiskey bottle. Another (a dachshund) has his midriff shot out chunk by chunk by a hail of bullets. Cowboy Bosko approaches the saloon swinging doors, cheerily greeting those inside, “Howdy, fellas.” Machine gun fire riddles his hat with bullet holes, after which the playful inhabitants of the establishment cheerily respond back, “Hi, Bosko.” Goopy Geer cameos as piano player, downing a house specialty from a tall glass atop the piano – which burns his whole wardrobe to a crisp. Goopy must be that tenth man who isn’t quite a man, as he effeminately shouts, “Whoop”, and sidles off in embarrassment at his partial nudity. Bosko takes over piano duties, with some dancers dancing in recycled animation from “Moonlight For Two”. In a poker player’s hand, two kings, a queen, and a Joker join in vocalizing with Bosko’s tune, until a bullet puts the singing Joker out of commission. Meanwhile, outside in the badlands, the Deadwood stage (free-wheeling) hurtles through the night, carrying a single passenger (Honey) and her trunk. The stage is beset by bandits, who emerge from behind a rock at the side of the road, their leader raising two six-guns as a sign for the coach to stop. But the coach entirely ignores him, passing so fast, the bandit and his guns are sent into a spiraling spin. The bandits are forced to re-mount and give chase. One shot knocks Honey’s trunk off the coach roof, and her wardrobe emerges, making a quick exit for the hills to escape the gunfire. As the coach hits a rock, the stage driver is ejected from his set, sliding down a cactus full of thorny needles, then hopping onto the back of a cattle skeleton, which comes to life and gallops away with the driver. A possible continuity error occurs, as a stranger, rather than the driver, enters the saloon in town to alert Bosko that the stage is being held up. (Where did thus guy learn of these events, since we’ve never seen him before?) In another continuity error, Bosko races outside for his horse, attempting to leap into the saddle, but lands on a hitching post that wasn’t there when Bosko arrived in town, riding the post around a few times in circles before being thrown to the ground. Boski finally gets into the saddle, and takes off after the bandits. In continuity error number three, Bosko’s hat disappears from his head, as the camera pulls back from a panning shot of Bosko galloping along on his horse, to reveal he is on a drawing board, surrounded by the real-life Hugh Harman (there is some dispute here, as Leonard Maltin’s “Of Mice and Magic” claims it is animator Walker Harman), Rudolf Ising, and Norman Blackburn. Rudolf asks the others, “Say, how’s Bosko going to save the girl?” “I don’t know”, shrugs Blackburn. “Well, we’ve gotta do something”, responds Ising. “Let’s go home”, suggests Harman. “Good idea”, concludes Ising, as everyone reaches for their hats and departs, while Bosko and his mount slow to a stop on their board, with Bosko blinking to the audience as if to say, “What just happened?”

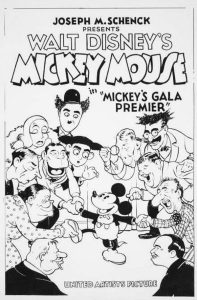

Generally, Mickey Mouse, with the exception of occasionally speaking to the audience from the screen (as, for example, in 1931’s “The Castaway”), would be among the last characters to outwardly admit he was not real. His barnyard world, and even his occasional jaunts into fantasy worlds, medieval times, or action-adventure settings, were as real to him as our own world is to us. But one time, at least in a dream, he became publicly aware of his own screen personality, and even of his own medium. This was in Mickey’s Gala Premier (Disney/UA, 7/1/33, Burt Gillett, dir.), a film which marked a first among animated stars. Mickey and his entourage, including Minne, Pluto, Horace Horsecollar, and Clarabelle Cow, attend a lavish, first-rate Hollywood premiere at Grauman’s Chinese Theater, to celebrate the debut of – a cartoon? And it is plain that Mickey is well-aware that the image that flashes on the screen is not some major equivalent of a live-action feature in his own world – as he sees the same United Artists opening and closing credits that we the audience would have seen in a first-run of the very cartoon we are viewing – so Mickey is sharing the same viewing experience as the humans who are watching him. He knows he is a cartoon star of pen and ink, working for Walt Disney as credited on screen. Thus, although he has risen to a prominence of respectability among the major luminaries of Hollywood, he is clearly not a part of their medium, but in a class by himself – the only drawn creation worthy of sharing a screen with the big boys and girls of the film industry. A far cry from the impromptu woodland projection of “Little Nell” in Van Beuren’s “Making “Em Move”.

Generally, Mickey Mouse, with the exception of occasionally speaking to the audience from the screen (as, for example, in 1931’s “The Castaway”), would be among the last characters to outwardly admit he was not real. His barnyard world, and even his occasional jaunts into fantasy worlds, medieval times, or action-adventure settings, were as real to him as our own world is to us. But one time, at least in a dream, he became publicly aware of his own screen personality, and even of his own medium. This was in Mickey’s Gala Premier (Disney/UA, 7/1/33, Burt Gillett, dir.), a film which marked a first among animated stars. Mickey and his entourage, including Minne, Pluto, Horace Horsecollar, and Clarabelle Cow, attend a lavish, first-rate Hollywood premiere at Grauman’s Chinese Theater, to celebrate the debut of – a cartoon? And it is plain that Mickey is well-aware that the image that flashes on the screen is not some major equivalent of a live-action feature in his own world – as he sees the same United Artists opening and closing credits that we the audience would have seen in a first-run of the very cartoon we are viewing – so Mickey is sharing the same viewing experience as the humans who are watching him. He knows he is a cartoon star of pen and ink, working for Walt Disney as credited on screen. Thus, although he has risen to a prominence of respectability among the major luminaries of Hollywood, he is clearly not a part of their medium, but in a class by himself – the only drawn creation worthy of sharing a screen with the big boys and girls of the film industry. A far cry from the impromptu woodland projection of “Little Nell” in Van Beuren’s “Making “Em Move”.

It should be noted that by the time this film came out, cartoons featuring Hollywood celebrities were nothing new. In fact, Charles Mintz had beaten Disney to the screen with two such substantial outings within the previous season, including Krazy Kat’s “Seeing Stars” and “Scrappy’s Party”, and probably had Scrappy’s “Movie Struck” in production when the Mickey short was released. But none of the Mintz shorts particularly pointed out that its starring characters were cartoons, thus falling more into the category of films about Hollywood, which could have equally passed in live-action if anyone could have afforded the budget. The Mintz shorts may have been the impetus for the creation of the Mickey in the first place, as it seemed to be becoming a race as to how many celebrities could be crammed into a six-to-seven minute reel. If such was the case, Disney may have prevailed in the race by a hair, given the massive cast that accompanies Mickey in this cartoon. Wikipedia has the best blow-by-blow description of where the celebrities appear, listing far more than I was able to easily identify, but in summary, the name roster includes Ben Turpin, Ford Sterling, Mack Swain, Harry Langdon, Chester Conklin, Wallace Beery, Marie Dressler, Lionel Barrymore, John Barrymore, Ethel Barrymore, Laurel and Hardy, the four Marx Brothers, Maurice Chevalier, Eddie Cantor, Jimmy Durante, Jean Harlow, Joan Crawford, Janet Gaynor, Harold Lloyd, Clark Gable, Edward G. Robinson, Adolphe Menjou, Sid Grauman, George Arliss, Joe E. Brown, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Mae West, Helen Hayes, William Powell, Chester Morris, Gloria Swanson, Rudy Vallee, Will H. Hays, Myrna Loy. Ed Wynn, Wheeler & Woolsey, Bela Lugosi, Fredric March, Boris Karloff, Douglas Fairbanks, Will Rogers, Greta Garbo, Constance Bennett, Warner Baxter, and allegedly, even Walt Disney!

It should be noted that by the time this film came out, cartoons featuring Hollywood celebrities were nothing new. In fact, Charles Mintz had beaten Disney to the screen with two such substantial outings within the previous season, including Krazy Kat’s “Seeing Stars” and “Scrappy’s Party”, and probably had Scrappy’s “Movie Struck” in production when the Mickey short was released. But none of the Mintz shorts particularly pointed out that its starring characters were cartoons, thus falling more into the category of films about Hollywood, which could have equally passed in live-action if anyone could have afforded the budget. The Mintz shorts may have been the impetus for the creation of the Mickey in the first place, as it seemed to be becoming a race as to how many celebrities could be crammed into a six-to-seven minute reel. If such was the case, Disney may have prevailed in the race by a hair, given the massive cast that accompanies Mickey in this cartoon. Wikipedia has the best blow-by-blow description of where the celebrities appear, listing far more than I was able to easily identify, but in summary, the name roster includes Ben Turpin, Ford Sterling, Mack Swain, Harry Langdon, Chester Conklin, Wallace Beery, Marie Dressler, Lionel Barrymore, John Barrymore, Ethel Barrymore, Laurel and Hardy, the four Marx Brothers, Maurice Chevalier, Eddie Cantor, Jimmy Durante, Jean Harlow, Joan Crawford, Janet Gaynor, Harold Lloyd, Clark Gable, Edward G. Robinson, Adolphe Menjou, Sid Grauman, George Arliss, Joe E. Brown, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Mae West, Helen Hayes, William Powell, Chester Morris, Gloria Swanson, Rudy Vallee, Will H. Hays, Myrna Loy. Ed Wynn, Wheeler & Woolsey, Bela Lugosi, Fredric March, Boris Karloff, Douglas Fairbanks, Will Rogers, Greta Garbo, Constance Bennett, Warner Baxter, and allegedly, even Walt Disney!

Anyway, Mickey attends his premiere, views a cartoon-within-a-cartoon (“Galloping Romance”, a sort of by-the-numbers Mickey and Peg Leg Pete chase epic, written deliberately corny), gets the audience swaying to the music and literally rolling in the aisles, and receives the laudits of all in attendance, including Greta Garbo, who ends the event smothering Mickey in kisses. (Where’s Minnie for the finale, and how come she’s not jealous? It might have been interesting if she had smacked Garbo in the face.) But perhaps the reason Minnie doesn’t show up is that the whole affair had been within Mickey’s dream, and it is only the affectionate slurps of Pluto bidding Mickey a good morning that he has been receiving as kisses. The mouse awakens in his own bedroom, his walls bedecked with autographed pictures of Hollywood celebrities. The nonplussed Mickey, disappointed, pushes Pluto away, and goes back to bed again, maybe in hopes of rejoining his wonderful dream.

Anyway, Mickey attends his premiere, views a cartoon-within-a-cartoon (“Galloping Romance”, a sort of by-the-numbers Mickey and Peg Leg Pete chase epic, written deliberately corny), gets the audience swaying to the music and literally rolling in the aisles, and receives the laudits of all in attendance, including Greta Garbo, who ends the event smothering Mickey in kisses. (Where’s Minnie for the finale, and how come she’s not jealous? It might have been interesting if she had smacked Garbo in the face.) But perhaps the reason Minnie doesn’t show up is that the whole affair had been within Mickey’s dream, and it is only the affectionate slurps of Pluto bidding Mickey a good morning that he has been receiving as kisses. The mouse awakens in his own bedroom, his walls bedecked with autographed pictures of Hollywood celebrities. The nonplussed Mickey, disappointed, pushes Pluto away, and goes back to bed again, maybe in hopes of rejoining his wonderful dream.

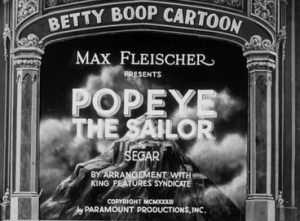

Popeye was probably the first character from the sound era to become consciously aware of his exposure as a character in other media. From his first appearance in Popeye the Sailor (Fleischer/Paramount, 7/13/33 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Roland Crandall, anim.), his entrance is heralded by a newspaper extra rolling hot off the presses, reading, “POPEYE A MOVIE STAR. The sailor with a ‘sock’ accepts movie contract”. The camera closes in on Popeye’s photo, as the sailor comes to life before our eyes, performing for the first time his theme song, socking various things on board a ship deck along the way to demonstrate his strength. A wall clock is shattered into miniature alarm clocks, a mounted fish into a pile of sardine cans, and a ship’s mast into clothespins. Popeye even reveals a personal secret – his slim, trim waistline is the result of wearing a corset underneath his sailor shirt! The rest of the film is a basic first appearance of the Popeye-Olive-Bluto triangle at a carnival, where Popeye, for the only time on-screen, meets Betty Boop, reprising her hula dance routine from “Betty Boop’s Bamboo Isle” in a sideshow. Popeye actually joins the dance, stealing the beard off a bearded lady to use as a grass skirt, and also averts the approach of a snake from a snake charmer, ny knocking the snake unconscious with the smoke from his pipe (a gag which would be later reused in “Wild Elephinks”). Bluto binds Olive up in railroad tracks (wrapping the steel bars around her), but Popeye eats his spinach, delivering a blow to Bluto and a nearby tree that creates a wooden coffin for Bluto to be nailed up inside. Popeye has insufficient time to free Olive, so just delivers a punch to the engine of the oncoming train, rendering it a deflated pile of rubble and shrapnel.

Popeye was probably the first character from the sound era to become consciously aware of his exposure as a character in other media. From his first appearance in Popeye the Sailor (Fleischer/Paramount, 7/13/33 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Roland Crandall, anim.), his entrance is heralded by a newspaper extra rolling hot off the presses, reading, “POPEYE A MOVIE STAR. The sailor with a ‘sock’ accepts movie contract”. The camera closes in on Popeye’s photo, as the sailor comes to life before our eyes, performing for the first time his theme song, socking various things on board a ship deck along the way to demonstrate his strength. A wall clock is shattered into miniature alarm clocks, a mounted fish into a pile of sardine cans, and a ship’s mast into clothespins. Popeye even reveals a personal secret – his slim, trim waistline is the result of wearing a corset underneath his sailor shirt! The rest of the film is a basic first appearance of the Popeye-Olive-Bluto triangle at a carnival, where Popeye, for the only time on-screen, meets Betty Boop, reprising her hula dance routine from “Betty Boop’s Bamboo Isle” in a sideshow. Popeye actually joins the dance, stealing the beard off a bearded lady to use as a grass skirt, and also averts the approach of a snake from a snake charmer, ny knocking the snake unconscious with the smoke from his pipe (a gag which would be later reused in “Wild Elephinks”). Bluto binds Olive up in railroad tracks (wrapping the steel bars around her), but Popeye eats his spinach, delivering a blow to Bluto and a nearby tree that creates a wooden coffin for Bluto to be nailed up inside. Popeye has insufficient time to free Olive, so just delivers a punch to the engine of the oncoming train, rendering it a deflated pile of rubble and shrapnel.

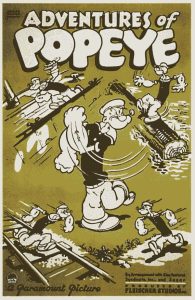

Fast-forwarding ahead momentarily to stay on the subject. Popeye becomes aware that his popularity has extended from the newspaper strip to the comic book trade in Adventures of Popeye (Fleischer/Paramount, 10/25/35 – Dave Fleischer, dir., no animator credits). This was the first of many Popeyes over the years to be a “cheater” – consisting primarily of a clip-fest from previous episodes. There is relatively-little new animation, most new footage being taken up by live-action material of a small boy purchasing a Popeye comic from a newsstand, then being called a sissy for it by a young bully. The bully musses up the younger boy’s hair, then delivers him a licking (most of the violence off-screen), pushing the young boy to the ground and making him cry. (The live footage is shot silent and overdubbed for dialogue, it appearing that at least the younger boy’s voice is likely supplied by Mae Questel). On the cover of the comic book, which has fallen to one side during the fight, Popeye’s head comes to life, turning to observe the defeated boy’s tears. Popeye’s pipe twirls in reaction, realizing that something must be done about it. Popeye’s arms reveal themselves alongside his visible head and shoulders, and he literally pulls himself out of the comic book cover, revealing his full torso not previously seen. He tells the boy he will show what he’s done before to guys who thought they were tough. Four extended clips are presented, by Popeye flipping pages from the comic book and leaping in and out of them. The clips include Popeye’s encounter with charging bulls from “I Eats My Spinach”, the finale train sequence and fight from “Popeye the Sailor”, a battle with jungle animals from “Wild Elephinks”, and the log-rolling sequence from “Axe Me Another”.

Fast-forwarding ahead momentarily to stay on the subject. Popeye becomes aware that his popularity has extended from the newspaper strip to the comic book trade in Adventures of Popeye (Fleischer/Paramount, 10/25/35 – Dave Fleischer, dir., no animator credits). This was the first of many Popeyes over the years to be a “cheater” – consisting primarily of a clip-fest from previous episodes. There is relatively-little new animation, most new footage being taken up by live-action material of a small boy purchasing a Popeye comic from a newsstand, then being called a sissy for it by a young bully. The bully musses up the younger boy’s hair, then delivers him a licking (most of the violence off-screen), pushing the young boy to the ground and making him cry. (The live footage is shot silent and overdubbed for dialogue, it appearing that at least the younger boy’s voice is likely supplied by Mae Questel). On the cover of the comic book, which has fallen to one side during the fight, Popeye’s head comes to life, turning to observe the defeated boy’s tears. Popeye’s pipe twirls in reaction, realizing that something must be done about it. Popeye’s arms reveal themselves alongside his visible head and shoulders, and he literally pulls himself out of the comic book cover, revealing his full torso not previously seen. He tells the boy he will show what he’s done before to guys who thought they were tough. Four extended clips are presented, by Popeye flipping pages from the comic book and leaping in and out of them. The clips include Popeye’s encounter with charging bulls from “I Eats My Spinach”, the finale train sequence and fight from “Popeye the Sailor”, a battle with jungle animals from “Wild Elephinks”, and the log-rolling sequence from “Axe Me Another”.

All clips are presented with altered soundtracks, allowing for the current voices of Jack Mercer, Gus Wickey, and Mae Questel to be substituted for previous cast members. Popeye suggests in closing that the boy will be strong to the finish if he eats his spinach, then hops back into his original position on the cover of the comic. The next shot shows the live boy holding an open, oversized spinach can to match Popeye’s usual secret weapon. It is difficult to tell what he is eating out of the can, as the weedy-looking plants within don’t look much like real spinach at all, and seem to be quite raw. The boy flexes an arm muscle, and, with the aid of some superimposed drawing effects, the muscle swells, revealing an image within of the rock of Gibraltar. The boy then confronts the bully, delivering a beating, and an upper cut which, with the aid of some photographic cutouts, launches the bully skyward, through the glass window of an upper-story bedroom of his home. (Perhaps this film needs a “Don’t try this at home” disclaimer, as we wonder how many kids were disappointed when they didn’t get the same results from eating their veggies.) The boy sings the closing bars of the Popeye theme to the audience, first in Questel’s child-voice, but the words “Popeye the sailor man” in Mercer’s, providing Mercer with the first opportunity to vocally imitate the unheard sound-effect of Popeye’s pipe with a “Woo Woo” – a substitution Mercer would continue to use in his personal appearances, on record, and in film tracks from later years throughout his career.

All clips are presented with altered soundtracks, allowing for the current voices of Jack Mercer, Gus Wickey, and Mae Questel to be substituted for previous cast members. Popeye suggests in closing that the boy will be strong to the finish if he eats his spinach, then hops back into his original position on the cover of the comic. The next shot shows the live boy holding an open, oversized spinach can to match Popeye’s usual secret weapon. It is difficult to tell what he is eating out of the can, as the weedy-looking plants within don’t look much like real spinach at all, and seem to be quite raw. The boy flexes an arm muscle, and, with the aid of some superimposed drawing effects, the muscle swells, revealing an image within of the rock of Gibraltar. The boy then confronts the bully, delivering a beating, and an upper cut which, with the aid of some photographic cutouts, launches the bully skyward, through the glass window of an upper-story bedroom of his home. (Perhaps this film needs a “Don’t try this at home” disclaimer, as we wonder how many kids were disappointed when they didn’t get the same results from eating their veggies.) The boy sings the closing bars of the Popeye theme to the audience, first in Questel’s child-voice, but the words “Popeye the sailor man” in Mercer’s, providing Mercer with the first opportunity to vocally imitate the unheard sound-effect of Popeye’s pipe with a “Woo Woo” – a substitution Mercer would continue to use in his personal appearances, on record, and in film tracks from later years throughout his career.

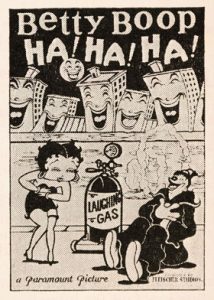

Betty Boop herself rarely projected cognizance of her own existence as a cartoon, although her early theme song, “Sweet Betty” proclaims in its original lyric from Boop-Oop-a-Doop (1932) her status as a “little queen of the animated screen”, and later lytic, “Made of pen and ink, she can with you with a wink.” In such film, Koko makes an appearances in a circus parade out of a large inkwell, but Betty does not share in the same manner of creation. But Betty would eventually admit to her origins in Ha! Ha! Ha! (Fleischer/Paramount, 3/2/34 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Roland Crandall, anim.). This film is virtually a sound return to the original Out of the Inkwell format, featuring Koko in his usual place on Max’s drawing board, but adding Betty, also fresh from the inkwell, for assistance. Betty actually gets drawn first by the unseen Max, who bids her good night as he leaves the studio. Koko emerges by pushing out the stopper of the inkwell, wipes off the excess ink, and proceeds to the remains of a candy bar left open upon Max’s desk. Koko gorges himself on a chunk of candy almost too big for his small mouth, but pauses when the side of his face swells. Inside his cheek, a cutaway x-ray view reveals two devil imps inside his tooth, hammering away on the nerve, then hitting each other accidentally with the hammers and fighting among themselves. Koko moans in pain, arousing Betty from the drawing board. Grabbing Max’s pen, Betty draws a new background of a dentisu’s office, and asks Koko to sit in the chair. Having Koko open wide, Betty gets a pair of clamps on the problem tooth, and attempts to performs an extraction – but the clamps give way, and Betty rolls backwards upon the floor. To ease Koko’s pain, Betty opens a tank of laughing gas, setting the valve wide open, raising a gauge needle from titters to hysterics. Koko becomes well-dosed, but the rising fumes reach Betty too, and soon she is as helpless as Koko. The gas continues to pour out, affecting objects in the office, creating a laughing cuckoo clock and typewriter (modified with animated effects upon live-action photos). The gas seeps ouside through the window, and further creates a laughing mailbox, fire alarm box, crowd of real people, a river bridge, automobiles, and even the gravestones from a graveyard, many of which utter the phrase, ‘Don’t make me laugh.” Betty and Koko finally can’t take any more, and disappear into the inkwell. The inkwell itself develops a face, engaging in uncontrollable guffaws, until it exhausts itself, and sags limply with its energy spent, as the film irises out.

Betty Boop herself rarely projected cognizance of her own existence as a cartoon, although her early theme song, “Sweet Betty” proclaims in its original lyric from Boop-Oop-a-Doop (1932) her status as a “little queen of the animated screen”, and later lytic, “Made of pen and ink, she can with you with a wink.” In such film, Koko makes an appearances in a circus parade out of a large inkwell, but Betty does not share in the same manner of creation. But Betty would eventually admit to her origins in Ha! Ha! Ha! (Fleischer/Paramount, 3/2/34 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Roland Crandall, anim.). This film is virtually a sound return to the original Out of the Inkwell format, featuring Koko in his usual place on Max’s drawing board, but adding Betty, also fresh from the inkwell, for assistance. Betty actually gets drawn first by the unseen Max, who bids her good night as he leaves the studio. Koko emerges by pushing out the stopper of the inkwell, wipes off the excess ink, and proceeds to the remains of a candy bar left open upon Max’s desk. Koko gorges himself on a chunk of candy almost too big for his small mouth, but pauses when the side of his face swells. Inside his cheek, a cutaway x-ray view reveals two devil imps inside his tooth, hammering away on the nerve, then hitting each other accidentally with the hammers and fighting among themselves. Koko moans in pain, arousing Betty from the drawing board. Grabbing Max’s pen, Betty draws a new background of a dentisu’s office, and asks Koko to sit in the chair. Having Koko open wide, Betty gets a pair of clamps on the problem tooth, and attempts to performs an extraction – but the clamps give way, and Betty rolls backwards upon the floor. To ease Koko’s pain, Betty opens a tank of laughing gas, setting the valve wide open, raising a gauge needle from titters to hysterics. Koko becomes well-dosed, but the rising fumes reach Betty too, and soon she is as helpless as Koko. The gas continues to pour out, affecting objects in the office, creating a laughing cuckoo clock and typewriter (modified with animated effects upon live-action photos). The gas seeps ouside through the window, and further creates a laughing mailbox, fire alarm box, crowd of real people, a river bridge, automobiles, and even the gravestones from a graveyard, many of which utter the phrase, ‘Don’t make me laugh.” Betty and Koko finally can’t take any more, and disappear into the inkwell. The inkwell itself develops a face, engaging in uncontrollable guffaws, until it exhausts itself, and sags limply with its energy spent, as the film irises out.

Another Fleischer cheater (the only one to appear in the Boop series) was entitled Betty Boop’s Rise to Fame (Fleischer/Paramount, 5/18/35 – Dave Fleischer, dir., no animator credits). The film begins with Max being interviewed by a reporter in live action. Max states that it takes 12,000 to 14,000 drawings to complete each picture, (What an increase from Mutt and Jeff’s 3,000!) He then proceeds to draw Betty on a drawing board, and asks her to go through her stuff for the man from the press. Three old backgrounds are pulled out by Max, and Betty asks for a lift on Max’s pen, to be placed onto the table with each background. First is the stage from “Stopping the Show”, where Betty performs her impressions of Helen Kane (with the same lawsuit-imposed cuts removing footage from the original depicting Helen’s name and face), Fannie Brice, and Maurice Chevalier. Then, a quick change of costume behind the inkwell, and Betty appears in her lei and hula skirt to perform her sensuous dance from “Betty Boop’s Bamboo Isle”. Finally, another costume change behind the bookends, and a jump into a background from “The Old Man of the Mountain”, for her song and dance with the Cab Calloway-voiced and rotoscoped title character. The Old Man pursues her out of the background, and Max takes a hand in it by offering Betty the inkwell to jump into. Betty’s landing splatters ink all over the reporter’s note pad and in the reporter’s eye. Betty asks from the inkwell if the reporter got everything, and the man, wiping ink out of his eye, acknowledges that he sure did. Betty bids us good night, and caps herself inside the inkwell.

Another Fleischer cheater (the only one to appear in the Boop series) was entitled Betty Boop’s Rise to Fame (Fleischer/Paramount, 5/18/35 – Dave Fleischer, dir., no animator credits). The film begins with Max being interviewed by a reporter in live action. Max states that it takes 12,000 to 14,000 drawings to complete each picture, (What an increase from Mutt and Jeff’s 3,000!) He then proceeds to draw Betty on a drawing board, and asks her to go through her stuff for the man from the press. Three old backgrounds are pulled out by Max, and Betty asks for a lift on Max’s pen, to be placed onto the table with each background. First is the stage from “Stopping the Show”, where Betty performs her impressions of Helen Kane (with the same lawsuit-imposed cuts removing footage from the original depicting Helen’s name and face), Fannie Brice, and Maurice Chevalier. Then, a quick change of costume behind the inkwell, and Betty appears in her lei and hula skirt to perform her sensuous dance from “Betty Boop’s Bamboo Isle”. Finally, another costume change behind the bookends, and a jump into a background from “The Old Man of the Mountain”, for her song and dance with the Cab Calloway-voiced and rotoscoped title character. The Old Man pursues her out of the background, and Max takes a hand in it by offering Betty the inkwell to jump into. Betty’s landing splatters ink all over the reporter’s note pad and in the reporter’s eye. Betty asks from the inkwell if the reporter got everything, and the man, wiping ink out of his eye, acknowledges that he sure did. Betty bids us good night, and caps herself inside the inkwell.

Betty would have two more visits to the inkwell in her career, which will be discussed in subsequent installments of this series.

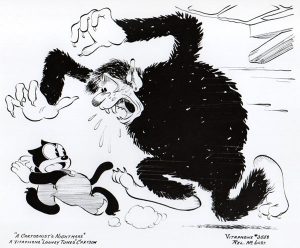

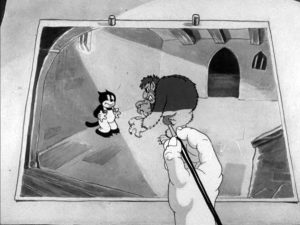

A Cartoonist’s Nightmare (Warner, Looney Tunes, 9/21/35 – Jack King, dir.) – Though Beans the Cat appears as a major supporting player, he does not receive starring credit on the titles. Presented entirely in 2-D animation, most of the footage goes to a realistically-depicted animator in a cartoon studio, who stays after closing time to finish up a scene, for which he has already produced a stack behind his chair of drawings piled about four feet tall. His present shot has Beans cornered in a room by the Beast from the previous color production, “Beauty and the Beast”. The animator declares that it looks like he’ll have to save Beans from the villain again, as he draws in on the background a set of steel bars between Beans and the Beast to keep the Beast from getting his hands on Beans. He leaves the drawing in such a state, as sleep overtakes the animator, and he nods off at his desk. Suddenly, the clawed hands of the Beast reach out of the drawing paper to grab the animator, dragging him into the cartoon world. The Beast carries the struggling animator out of the room on the screen – and the animator has forgotten to draw Beans a means of escape, leaving the cat trapped behind the iron bars. The Beast takes the animator through a door labeled “Cartoon Villains. Within are several wall posters of various villains, some new, some familiar (including an octopus seen in “Mister and Mrs. Is the Name’, a Mad Doctor who I believe appeared in “Buddy the Detective”, and a cat villain whom I cannot precisely place). They come off of their posters, delivering several socks to the animator, while the Beast holds him upside down and uses him like a punching bag. The villains sing a taunting song about the tables being turned upon the animator by his own creations. They then hand him a pencil, and command him to draw a deep pit, into which they intend to fling him.

A Cartoonist’s Nightmare (Warner, Looney Tunes, 9/21/35 – Jack King, dir.) – Though Beans the Cat appears as a major supporting player, he does not receive starring credit on the titles. Presented entirely in 2-D animation, most of the footage goes to a realistically-depicted animator in a cartoon studio, who stays after closing time to finish up a scene, for which he has already produced a stack behind his chair of drawings piled about four feet tall. His present shot has Beans cornered in a room by the Beast from the previous color production, “Beauty and the Beast”. The animator declares that it looks like he’ll have to save Beans from the villain again, as he draws in on the background a set of steel bars between Beans and the Beast to keep the Beast from getting his hands on Beans. He leaves the drawing in such a state, as sleep overtakes the animator, and he nods off at his desk. Suddenly, the clawed hands of the Beast reach out of the drawing paper to grab the animator, dragging him into the cartoon world. The Beast carries the struggling animator out of the room on the screen – and the animator has forgotten to draw Beans a means of escape, leaving the cat trapped behind the iron bars. The Beast takes the animator through a door labeled “Cartoon Villains. Within are several wall posters of various villains, some new, some familiar (including an octopus seen in “Mister and Mrs. Is the Name’, a Mad Doctor who I believe appeared in “Buddy the Detective”, and a cat villain whom I cannot precisely place). They come off of their posters, delivering several socks to the animator, while the Beast holds him upside down and uses him like a punching bag. The villains sing a taunting song about the tables being turned upon the animator by his own creations. They then hand him a pencil, and command him to draw a deep pit, into which they intend to fling him.

Meanwhile, from out of nowhere, an animal prison matron appears at Beans’s jail bars, and hands Beans a loaf of bread. The bread contains a file in it, which Beans uses to saw through the bars. The animator completes his drawing of the pit, and the Beast flings him into it, the animator’s pencil remaining left behind on the floor above. At the base of the pit is a crocodile pool, where a croc waits with jaws wide. Fortunately, there is a protruding branch from the side wall of the pit, on which the animator’s pants catch, snatching him up and out of the crocodile’s mouth. The animator emerges wearing the crocodile’s mammoth set of false teeth – but he unwisely tosses the teeth back to the crocodile. Above, Beans has caught up to the chamber of the villains, and ponders how to distract them. Acquiring from nowhere a prop pair of cartoon boots, Beans shoos them into the room with the villains, where the boots deliver a kick in the pants to the Beast. Beans stands in the doorway with a “Nyah Nyah”, and gets the villains to chase him. They emerge into the corridor, but pass Beans, who is hiding in a barrel. Beans re-enters the chamber, and hears the calls for help of the animator within the pit. Beans tosses the pencil down to the animator, who uses it to draw an extension ladder with which to climb out. Beans sets a trap for the villains, producing from within his outfit a grease gun, and laying a trail of slippery grease between the pit and the door. Beans then “Nyah Nyah”’s again, giving away his position in the room. The villains charge in, slip on the grease, and fall into the pit. The animator then produces an eraser, and erases the pit from existence entirely, sealing the villains in. The animator and Beans shake hands in victory, but the scene dissolves, as the hand of Beans becomes the hand of the studio night watchman, stirring the animator from his slumber. The awakened animator looks down at his drawing board, and decides to remove the Beast entirely, sucking both the image of the Beast and the iron bars back inro a fountain pen. With the pen, he then draws a large plate of ice cream for Beans as a reward, which Beans happily devours, for the iris out.

Meanwhile, from out of nowhere, an animal prison matron appears at Beans’s jail bars, and hands Beans a loaf of bread. The bread contains a file in it, which Beans uses to saw through the bars. The animator completes his drawing of the pit, and the Beast flings him into it, the animator’s pencil remaining left behind on the floor above. At the base of the pit is a crocodile pool, where a croc waits with jaws wide. Fortunately, there is a protruding branch from the side wall of the pit, on which the animator’s pants catch, snatching him up and out of the crocodile’s mouth. The animator emerges wearing the crocodile’s mammoth set of false teeth – but he unwisely tosses the teeth back to the crocodile. Above, Beans has caught up to the chamber of the villains, and ponders how to distract them. Acquiring from nowhere a prop pair of cartoon boots, Beans shoos them into the room with the villains, where the boots deliver a kick in the pants to the Beast. Beans stands in the doorway with a “Nyah Nyah”, and gets the villains to chase him. They emerge into the corridor, but pass Beans, who is hiding in a barrel. Beans re-enters the chamber, and hears the calls for help of the animator within the pit. Beans tosses the pencil down to the animator, who uses it to draw an extension ladder with which to climb out. Beans sets a trap for the villains, producing from within his outfit a grease gun, and laying a trail of slippery grease between the pit and the door. Beans then “Nyah Nyah”’s again, giving away his position in the room. The villains charge in, slip on the grease, and fall into the pit. The animator then produces an eraser, and erases the pit from existence entirely, sealing the villains in. The animator and Beans shake hands in victory, but the scene dissolves, as the hand of Beans becomes the hand of the studio night watchman, stirring the animator from his slumber. The awakened animator looks down at his drawing board, and decides to remove the Beast entirely, sucking both the image of the Beast and the iron bars back inro a fountain pen. With the pen, he then draws a large plate of ice cream for Beans as a reward, which Beans happily devours, for the iris out.

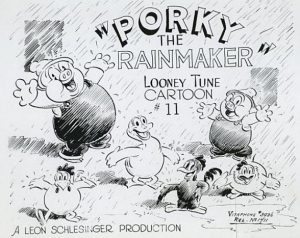

Porky Pig, who originated in the same first cartoon as Beans, took a little longer to acknowledge his cartoon existence. It would take the arrival of Tex Avery to allow Porky to become increasingly “toony”, breaking the fourth wall and pulling camera tricks that only a cartoon character could do. One of the earliest was in Porky the Rainmaker (8/1/36), in which a box full of weather-inducing pills has been purchased by Porky, to bring an end to a severe drought. While the rain is finally produced, all manner of other weather conditions have also resulted from the farmyard animals swallowing other pills from the box. The film ends with all of the animals enduring the weather phenomena of the pills they swallowed, including a goose who has swallowed a wind pill. The goose is blown by the wind through the closing iris just as the film ends, landing him outside the screen as the blackness of the iris closes entirely. The goose frantically knocks on the bare screen, demanding to be let back inside. The arm of Porky Pig forces the iris open just far enough to allow his arm to reach out, grab the goose by the neck, and yank him back into the cartoon before the hole closes once again. Similarly, in “Porky’s Garden” (9/11/37), a neighboring Italian farmer competes with Porky for first prize at the county fair for the largest home-grown product. He allows his own chickens to feast upon Porky’s vegetables, leaving the pig with only one pumpkin left for an entry. The fattened fowl are led by the Italian to the fair, but pass a medicine show wagon, where the hawker is selling reducing pills. The chickens each devour a pill, and, just as the judge hands the prize to the Italian, the chickens all shrink down to chick size. A twin pair of iris outs close upon the Italian and Porky – but Porky again manages to reopen them from within, allowing him to reach from one iris over to the Italian in the other, grabbing the sack of prize money away from him and into Porky’s iris, as both circles close once again.

Porky Pig, who originated in the same first cartoon as Beans, took a little longer to acknowledge his cartoon existence. It would take the arrival of Tex Avery to allow Porky to become increasingly “toony”, breaking the fourth wall and pulling camera tricks that only a cartoon character could do. One of the earliest was in Porky the Rainmaker (8/1/36), in which a box full of weather-inducing pills has been purchased by Porky, to bring an end to a severe drought. While the rain is finally produced, all manner of other weather conditions have also resulted from the farmyard animals swallowing other pills from the box. The film ends with all of the animals enduring the weather phenomena of the pills they swallowed, including a goose who has swallowed a wind pill. The goose is blown by the wind through the closing iris just as the film ends, landing him outside the screen as the blackness of the iris closes entirely. The goose frantically knocks on the bare screen, demanding to be let back inside. The arm of Porky Pig forces the iris open just far enough to allow his arm to reach out, grab the goose by the neck, and yank him back into the cartoon before the hole closes once again. Similarly, in “Porky’s Garden” (9/11/37), a neighboring Italian farmer competes with Porky for first prize at the county fair for the largest home-grown product. He allows his own chickens to feast upon Porky’s vegetables, leaving the pig with only one pumpkin left for an entry. The fattened fowl are led by the Italian to the fair, but pass a medicine show wagon, where the hawker is selling reducing pills. The chickens each devour a pill, and, just as the judge hands the prize to the Italian, the chickens all shrink down to chick size. A twin pair of iris outs close upon the Italian and Porky – but Porky again manages to reopen them from within, allowing him to reach from one iris over to the Italian in the other, grabbing the sack of prize money away from him and into Porky’s iris, as both circles close once again.

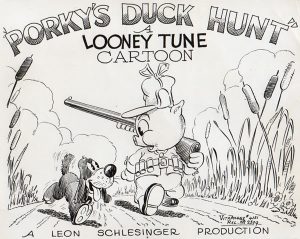

Porky’s Duck Hunt (4/17/37), however, clearly marks Porky’s awareness that this is only a cartoon. The film is largely a prototype for what would become standard fare for Elmer Fudd – a duck hunting trip, with both predictable and unexpected gags. A quiet lake looks deserted, until a duck flies overhead. Suddenly, every duck blind bristles with firing shotguns from a bevy of hunters, their shots raising a complete cloud of smoke over the pond. When the smoke clears, the dick nevertheless has been missed entirely, causing the hunters in unison to holler, “Aw, shucks,” A cross-eyed hunter with equally-crossed gun barrels fires a late shot into the air, and downs two airplanes in flames. Daffy Duck makes his debut, hiding among the decoys, then drawing a shot from Porky that shatters a stray floating barrel of booze. The barrel intoxicates the local fish, who commandeer a rowboat, and serenade in an inebriated version of “Moonlight Bay”. Porky gives the first signals of his screen consciousness, breaking the fourth wall to comment to the audience, “Th-th-there’s something f-f-fishy about that.” But the real breakthrough is when Porky thinks he’s plugged Daffy, and instructs his dog Rin Tin Tin to retrieve the mallard. The dog swims out, disappears with the duck below the water surface, then his bubble trail leads back to land. But it is not the dog who rises from the water. Instead, Daffy disgustedly tosses the unconscious mutt back onto shore. Porky immediately reaches inside his coat, producing a small book which he thumbs through, then shouts to Daffy, “H-h-hey, th-th-that wasn’t in the sc-sc-script!” The duck responds, “Don’t let it worry ya, Skipper. I’m just a crazy darnfool duck”, and breaks into a fit of “Woo Woo”s all across the pond. By the end of the film, Daffy is well aware he is a cartoon character, too – spending the last six seconds of the cartoon hopping and spinning like a madman all over the letters of the “That’s All, Folks” end card. This creative and memorable scene was lost for decades on all television release prints from Guild Films, but has finally resurfaced in recent decades, and become such a fan favorite, it inspired a new updated frenzy for Daffy over credits which has been recently in use by Warner Animation, adding the touch of Porky Pig pulling Daffy back inside the Warner shield to stop the madness.

Porky’s Duck Hunt (4/17/37), however, clearly marks Porky’s awareness that this is only a cartoon. The film is largely a prototype for what would become standard fare for Elmer Fudd – a duck hunting trip, with both predictable and unexpected gags. A quiet lake looks deserted, until a duck flies overhead. Suddenly, every duck blind bristles with firing shotguns from a bevy of hunters, their shots raising a complete cloud of smoke over the pond. When the smoke clears, the dick nevertheless has been missed entirely, causing the hunters in unison to holler, “Aw, shucks,” A cross-eyed hunter with equally-crossed gun barrels fires a late shot into the air, and downs two airplanes in flames. Daffy Duck makes his debut, hiding among the decoys, then drawing a shot from Porky that shatters a stray floating barrel of booze. The barrel intoxicates the local fish, who commandeer a rowboat, and serenade in an inebriated version of “Moonlight Bay”. Porky gives the first signals of his screen consciousness, breaking the fourth wall to comment to the audience, “Th-th-there’s something f-f-fishy about that.” But the real breakthrough is when Porky thinks he’s plugged Daffy, and instructs his dog Rin Tin Tin to retrieve the mallard. The dog swims out, disappears with the duck below the water surface, then his bubble trail leads back to land. But it is not the dog who rises from the water. Instead, Daffy disgustedly tosses the unconscious mutt back onto shore. Porky immediately reaches inside his coat, producing a small book which he thumbs through, then shouts to Daffy, “H-h-hey, th-th-that wasn’t in the sc-sc-script!” The duck responds, “Don’t let it worry ya, Skipper. I’m just a crazy darnfool duck”, and breaks into a fit of “Woo Woo”s all across the pond. By the end of the film, Daffy is well aware he is a cartoon character, too – spending the last six seconds of the cartoon hopping and spinning like a madman all over the letters of the “That’s All, Folks” end card. This creative and memorable scene was lost for decades on all television release prints from Guild Films, but has finally resurfaced in recent decades, and become such a fan favorite, it inspired a new updated frenzy for Daffy over credits which has been recently in use by Warner Animation, adding the touch of Porky Pig pulling Daffy back inside the Warner shield to stop the madness.

The later 30’s, next time.