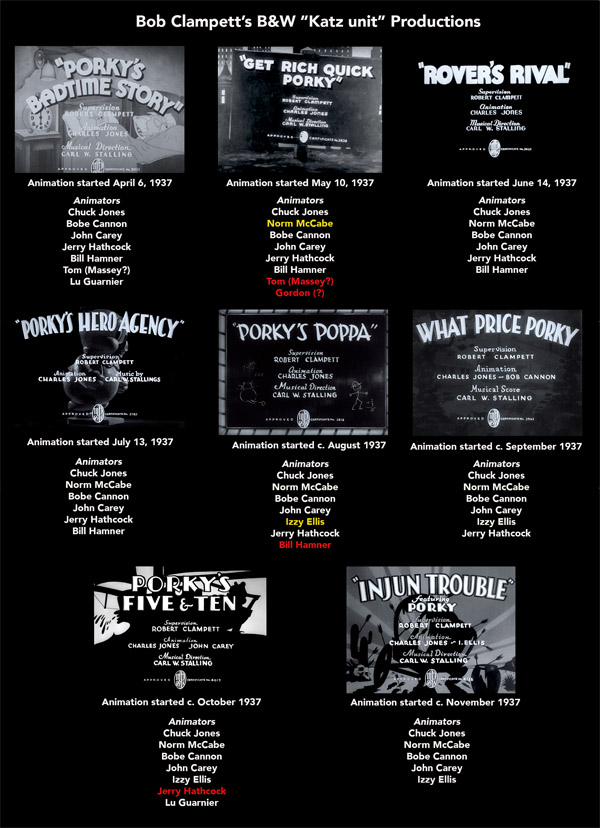

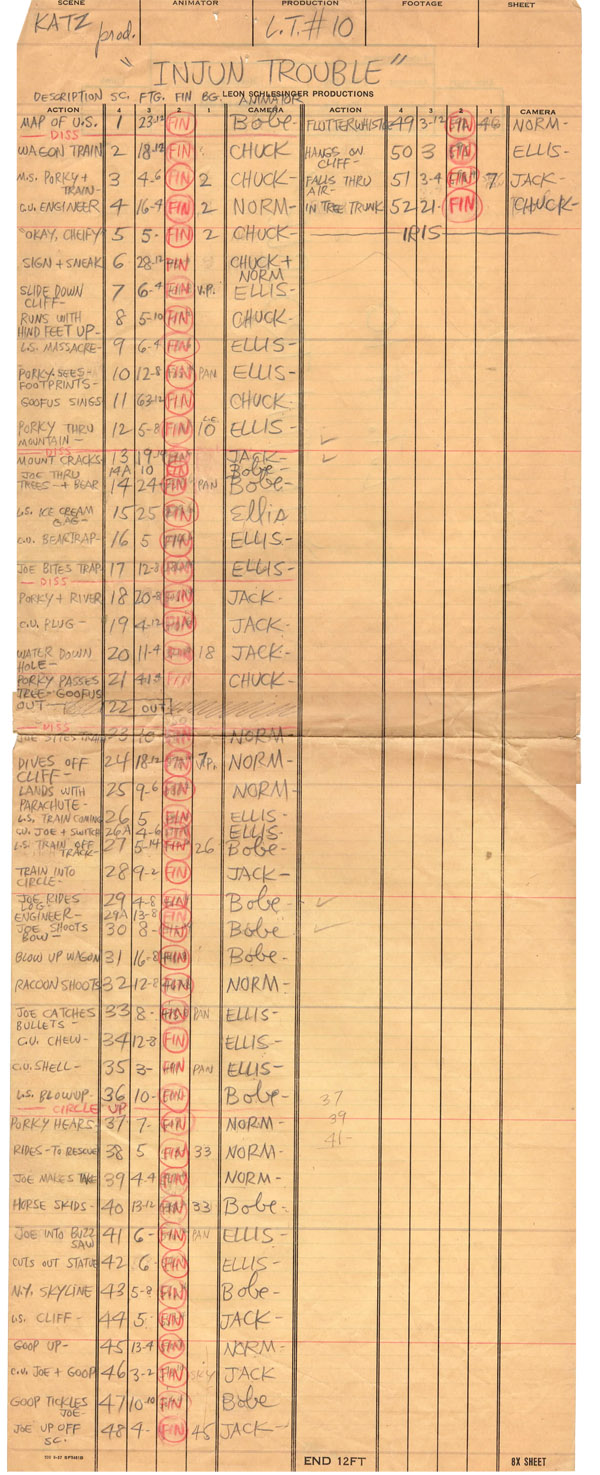

As previously mentioned, the “dope sheets” (animator drafts) in Bob Clampett’s first season of black-and-white Looney Tunes interpret the fluctuation of his animation unit. Jerry Hathcock, credited on the production scene drafts in Clampett’s first seven cartoons, does not appear in the draft for Injun Trouble, suggesting his decampment from the studio. (Hathcock found a job at Walt Disney’s, though the Archives have no definite date for his hiring.)

The “Katz unit” timeline up to this point is illustrated here: yellow signifies a new animator on staff, and red indicates an animator’s last known cartoon for Clampett. This excludes 1939’s Polar Pals and Jeepers Creepers, a pair of animator breakdowns exclusive to Patreon; the page also contains a revised and updated post on Get Rich Quick Porky, and detailed articles on Rover’s Rival, Porky’s Poppa, and Porky’s Five & Ten.

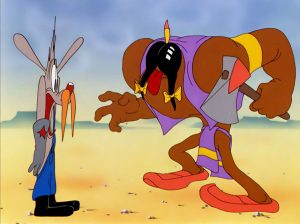

As What Price Porky’s burlesqued World War I-era movies, Injun Trouble parodies “wagon train” Westerns—a subgenre common since the silent film era. Raoul Walsh’s epic The Big Trail (Fox, 1930) laid the groundwork for motion pictures that dramatized the historic Western expansion. The film’s protagonist, Brock Coleman, played by John Wayne in his first lead role, guides a caravan from the Mississippi River bound for the prospective West. En route, the settlers and their covered wagons soon are besieged by a horde of Native Americans on horseback.

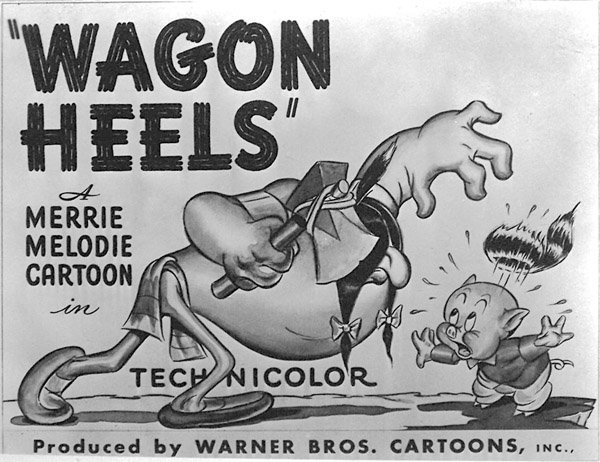

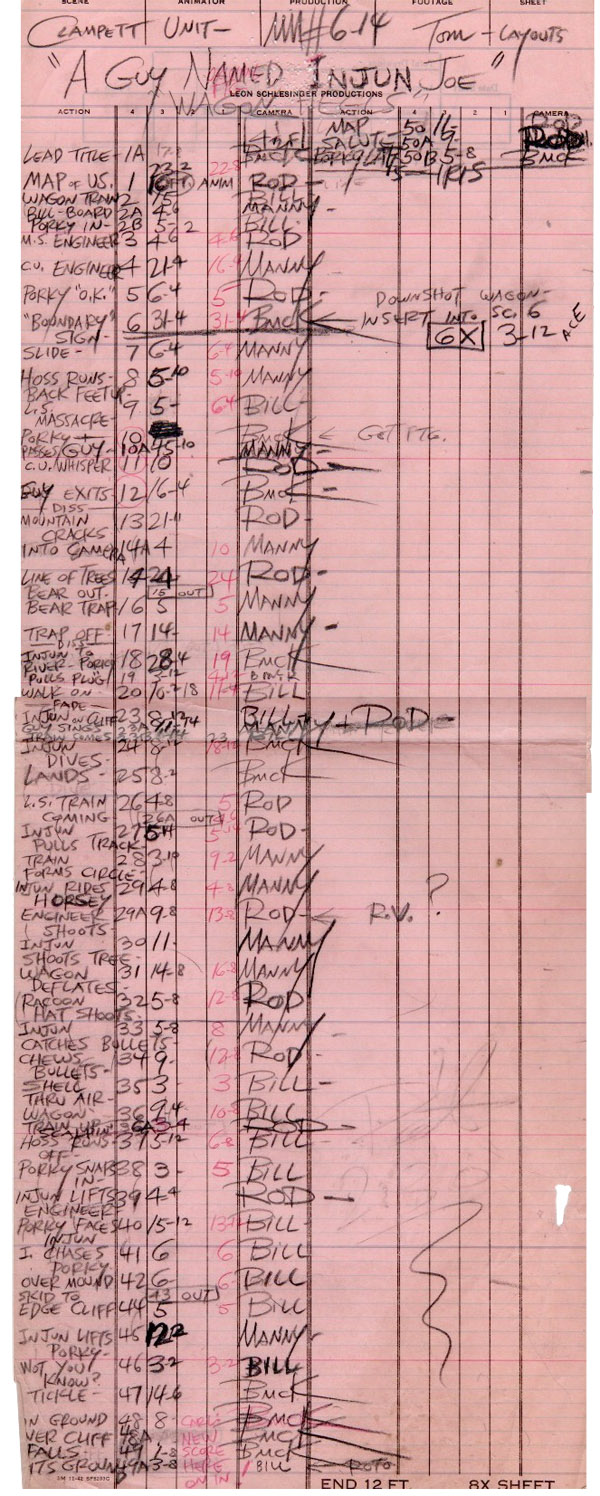

A few years later, Clampett chose to overhaul Injun Trouble, then under the working title “A Guy Named Injun Joe,” a titular spoof on Victor Fleming’s MGM feature A Guy Named Joe, released nationally in March 1944. By then, the Clampett unit had been making color cartoons for nearly three years, bolstered by a corps of Warners’ strongest animators. Clampett previously reworked his directorial debut, Porky’s Badtime Story, as Tick Tock Tuckered, released in April 1944. Wartime shortages, Clampett said, prompted these color remakes. While a reasonable factor, Phil Monroe, an animator briefly in the Clampett unit, confessed in an interview that the director often ran behind schedule during production. Monroe’s remark seems more plausible; the other units did not remake their earlier shorts as Clampett did. (Further Clampett production delays begat the remake Slightly Daffy—using 1939’s Scalp Trouble as its basis—and a project ultimately transferred to Friz Freleng.)

Studio records for Wagon Heels indicate that Mel Blanc and Robert C. Bruce recorded their lines in April and June 1944 — Mel Blanc’s dialogue tracks took place on April 1 and 22, with an additional session on June 10; Robert C. Bruce’s resonant narration that bookends the cartoon was recorded a week earlier, on June 3. (Mel was brought in for a “pick-up” session much later, on February 10, 1945.) Regarding behind-the-scenes chronology, animator Izzy Ellis received screen credit in Injun Trouble and Wagon Heels but did not animate any footage in the latter film. Bob McKimson, the studio’s top animator, handled many scenes in Wagon Heels without credit; by August 1944, McKimson was promoted to the director’s chair, while Izzy Ellis bounced between Clampett and McKimson’s respective crews by October. This might account for the small clerical error in the main title sequence.

Studio records for Wagon Heels indicate that Mel Blanc and Robert C. Bruce recorded their lines in April and June 1944 — Mel Blanc’s dialogue tracks took place on April 1 and 22, with an additional session on June 10; Robert C. Bruce’s resonant narration that bookends the cartoon was recorded a week earlier, on June 3. (Mel was brought in for a “pick-up” session much later, on February 10, 1945.) Regarding behind-the-scenes chronology, animator Izzy Ellis received screen credit in Injun Trouble and Wagon Heels but did not animate any footage in the latter film. Bob McKimson, the studio’s top animator, handled many scenes in Wagon Heels without credit; by August 1944, McKimson was promoted to the director’s chair, while Izzy Ellis bounced between Clampett and McKimson’s respective crews by October. This might account for the small clerical error in the main title sequence.

Injun Trouble and Wagon Heels reveal a map of the United States, represented by a thin strip of land on the East Coast, while the rest of the country is the property of Injun Joe. Wagon Heels places the narrative in 1849 when thousands flooded California during the Gold Rush (though the cartoon does not mention gold.) Injun Joe is introduced in its opening, touted as the “Superchief,” a reference to the Super Chief luxury passenger train that ran between Chicago and Los Angeles (from 1936 to 1971). By 1944, the Super Chief was a popular means of travel, often used by Hollywood celebrities headed East. (Freleng explicitly references the Super Chief in Hare Trigger, released a few months before Wagon Heels.)

Both films add anachronistic gags that skew the tropes of Western cinema and American history: an ox-drawn wagon train functions like a modern railroad car, with a smokestack on the engine and cattle that speed like a locomotive. Injun Trouble displays one carriage that bears the label “N.Y.R.R.,” a takeoff on the New York Central Railroad (N.Y.C.R.R.), one of the largest of the era. The caravan in Wagon Heels, which now boasts a contemporary dining and smoking car, carries guests that resemble the cartoon studio’s executive members in hierarchal order: studio head Eddie Selzer and his assistant Ray Katz in one carriage, with production manager Johnny Burton in the dining car. (Shortly before the cartoon’s release, Katz had left Warners due to health concerns by April 1945.) The wagon train then passes a sign that reads, “Is this trip really necessary?” This slogan underlined railroad travel’s importance to the war effort, encouraging American citizens to conserve oil, gas, and rubber.

Both films add anachronistic gags that skew the tropes of Western cinema and American history: an ox-drawn wagon train functions like a modern railroad car, with a smokestack on the engine and cattle that speed like a locomotive. Injun Trouble displays one carriage that bears the label “N.Y.R.R.,” a takeoff on the New York Central Railroad (N.Y.C.R.R.), one of the largest of the era. The caravan in Wagon Heels, which now boasts a contemporary dining and smoking car, carries guests that resemble the cartoon studio’s executive members in hierarchal order: studio head Eddie Selzer and his assistant Ray Katz in one carriage, with production manager Johnny Burton in the dining car. (Shortly before the cartoon’s release, Katz had left Warners due to health concerns by April 1945.) The wagon train then passes a sign that reads, “Is this trip really necessary?” This slogan underlined railroad travel’s importance to the war effort, encouraging American citizens to conserve oil, gas, and rubber.

Our hero, Porky Pig, is dispatched on a scouting mission by an engineer who continuously spits tobacco during his dialogue. The later remake curbed the expectoration, presumably due to an edict in the Production Code. (Porky’s black steed spits out tobacco after Porky’s response in Injun Trouble, but not in Wagon Heels.) Porky and his horse tip-toe across the boundary line of Injun Joe’s territory and look down below a cliff. Shocked at their discovery, they both slide down the cliffside to investigate. (Clampett inserts a point-of-view down shot of the wagon train massacre in Wagon Heels before their shocked reactions.) Porky and his horse find the destroyed remains of a prairie wagon annihilated by Injun Joe, whose massive figure has cast a giant hole through a mountain—hat and feather included!

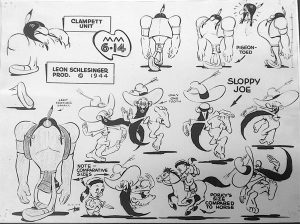

In the following sequence, Clampett relies on Chuck Jones’s strong draftsmanship in the character layouts and animation—a valuable benchmark for the Katz unit in their first production season. While the pair track Injun Joe’s footprints, Porky encounters a long-bearded pioneer that has survived the onslaught. The bearded twerp, named “Goofus” in the production draft for Injun Trouble and mentioned by name in Wagon Heels as “Sloppy Moe,” defines Clampett’s outlandish sensibilities at its core; in both films, the interloper revels in his lunacy when he taunts Porky with his tempting secret about Injun Joe. The pioneer’s design in the earlier film also suggests the kinetically drawn eccentrics of Milt Gross—an obvious and tremendous influence in Clampett’s cartoons. Porky gives a baffled expression to the camera when “Goofus” zips out into the horizon, and the search for Injun Joe continues. (By contrast, in Wagon Heels, Porky disregards Sloppy Moe’s cryptic mystery with a shrug.)

In the following sequence, Clampett relies on Chuck Jones’s strong draftsmanship in the character layouts and animation—a valuable benchmark for the Katz unit in their first production season. While the pair track Injun Joe’s footprints, Porky encounters a long-bearded pioneer that has survived the onslaught. The bearded twerp, named “Goofus” in the production draft for Injun Trouble and mentioned by name in Wagon Heels as “Sloppy Moe,” defines Clampett’s outlandish sensibilities at its core; in both films, the interloper revels in his lunacy when he taunts Porky with his tempting secret about Injun Joe. The pioneer’s design in the earlier film also suggests the kinetically drawn eccentrics of Milt Gross—an obvious and tremendous influence in Clampett’s cartoons. Porky gives a baffled expression to the camera when “Goofus” zips out into the horizon, and the search for Injun Joe continues. (By contrast, in Wagon Heels, Porky disregards Sloppy Moe’s cryptic mystery with a shrug.)

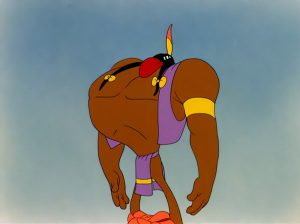

Meanwhile, Injun Joe’s incredible feats of strength and ferocity are on full display in our introduction; mountains and tree trunks break apart and split open in his path, and he reduces a large bear to a wailing baby cub with a domineering snarl. Wagon Heels establishes Joe as a more ominous force of nature. Tom McKimson, Clampett’s layout man and character model artist, redesigned Joe so that his hair covers his eyes; camera shakes are also implemented to accentuate Joe’s mighty steps.

Injun Trouble shows Joe detaching a mountaintop that transforms into the shape of an ice cream dish when gifted to the little bear. Before the cub can enjoy his peace offering, Injun Joe gobbles up the large mound and travels onward. (One might say this was a deliberate play on the archaic term “Indian giver.”) Clampett altered the scene for its remake with a more succinct payoff: the bear cub cries to the audience, “I’m only three and a half years old,” a direct reference to Little Matilda from radio’s The Abbott and Costello Show — a catchphrase the director frequently borrowed in several of his Warners cartoons. Clampett then wisely injects an added scene of Joe stomping towards the camera in perspective as his weight impacts the ground: a potent reminder of his dangerous nature. Joe then gets his foot caught in a bear trap and undauntingly bites back—the trap yells and scampers away in pain. (Clampett reused this gag in 1940’s The Chewin’ Bruin, with a grizzly bear in place of Injun Joe.)

Injun Trouble shows Joe detaching a mountaintop that transforms into the shape of an ice cream dish when gifted to the little bear. Before the cub can enjoy his peace offering, Injun Joe gobbles up the large mound and travels onward. (One might say this was a deliberate play on the archaic term “Indian giver.”) Clampett altered the scene for its remake with a more succinct payoff: the bear cub cries to the audience, “I’m only three and a half years old,” a direct reference to Little Matilda from radio’s The Abbott and Costello Show — a catchphrase the director frequently borrowed in several of his Warners cartoons. Clampett then wisely injects an added scene of Joe stomping towards the camera in perspective as his weight impacts the ground: a potent reminder of his dangerous nature. Joe then gets his foot caught in a bear trap and undauntingly bites back—the trap yells and scampers away in pain. (Clampett reused this gag in 1940’s The Chewin’ Bruin, with a grizzly bear in place of Injun Joe.)

Back to Porky and his horse, the two find a stream that blocks their trail; the steed rolls up his sleeve and removes a bathtub plug, which drains the water and allows them to cross. This scene, as staged in Injun Trouble, presents a weak story point: Porky and his horse could leap over or wade through the river quite easily since its size does not lend itself to a precarious obstacle. In Wagon Heels, Clampett exaggerates it to an “impassible” stream, which, in a more effective story element, Injun Joe submerges into the water and emerges out the other side in less than a second before Porky enters the scene.

Perched on a clifftop, Injun Joe spots the wagon train shown earlier in the cartoon. Wagon Heels poses a more dynamic composition, using deep space and exaggerated scale to emphasize Joe’s imposing stature as he surveys the caravan from afar. The excitable Sloppy Moe reappears and stands on a root which Injun Joe promptly snips off. Bob Clampett voiced the zany pioneer; sharp ears can discern the echo and background noise on the soundtrack during the scene, reflecting that the director recorded his vocals in haste. The production draft gives joint credit to Manny Gould and Rod Scribner for the shot—Scribner animated the few frames of Sloppy Moe’s reaction (and descent) after Injun Joe cuts the branch.

Perched on a clifftop, Injun Joe spots the wagon train shown earlier in the cartoon. Wagon Heels poses a more dynamic composition, using deep space and exaggerated scale to emphasize Joe’s imposing stature as he surveys the caravan from afar. The excitable Sloppy Moe reappears and stands on a root which Injun Joe promptly snips off. Bob Clampett voiced the zany pioneer; sharp ears can discern the echo and background noise on the soundtrack during the scene, reflecting that the director recorded his vocals in haste. The production draft gives joint credit to Manny Gould and Rod Scribner for the shot—Scribner animated the few frames of Sloppy Moe’s reaction (and descent) after Injun Joe cuts the branch.

Injun Joe’s plunge to the ground is handled differently in both films: in Injun Trouble, Joe “dives” off the cliff, spreading his vest like a plane’s wings—his nosedive morphs him into an aircraft—and parachutes for a safe landing; Wagon Heels has Joe unaffected by the force of gravity when he falls and lands, which causes the foreground element to bound under him, his enormous frame rock-solid throughout. Clampett hinges on the prairie wagon as a modern locomotive, furthering the metaphor when Injun Joe diverts the wagoners by manipulating a tree trunk in the form of a railroad switch. In Wagon Heels, Joe uses his strength to reshape the road path with his bare hands.

Now trapped, the pioneers quickly circle their wagons; in the earlier film, Injun Joe rides on a log like a child’s hobby horse around their fortress. (Wagon Heels has Joe ride on a genuine hobby horse.) Injun Trouble’s wagon attack draws a parallel to the earlier What Price Porky with its use of anachronistic weaponry: after the wagon engineer fires at Injun Joe with his Old West blunderbuss, his ox-team retorts with an M1917 Browning machine gun, used by the US Army during World War I. Shortly afterward, one pioneer, donning a coonskin cap, fires and then reloads his rifle—an actual raccoon then stands and fires a miniature “Tommy gun”! Wagon Heels jettisons the cattle action, but the gag with the coonskin cap remains, replacing the little raccoon’s sub-machine gun with a slingshot.

Now trapped, the pioneers quickly circle their wagons; in the earlier film, Injun Joe rides on a log like a child’s hobby horse around their fortress. (Wagon Heels has Joe ride on a genuine hobby horse.) Injun Trouble’s wagon attack draws a parallel to the earlier What Price Porky with its use of anachronistic weaponry: after the wagon engineer fires at Injun Joe with his Old West blunderbuss, his ox-team retorts with an M1917 Browning machine gun, used by the US Army during World War I. Shortly afterward, one pioneer, donning a coonskin cap, fires and then reloads his rifle—an actual raccoon then stands and fires a miniature “Tommy gun”! Wagon Heels jettisons the cattle action, but the gag with the coonskin cap remains, replacing the little raccoon’s sub-machine gun with a slingshot.

Injun Joe, in the original film, transforms his log into a bow, firing at the settlers with oversized arrows as he gallops along. Clampett restages the gag in Wagon Heels with another feat of strength: now Joe shoots arrows with a firmly rooted tree trunk as his bow. The pioneers fire rounds at Injun Joe, but to no avail: he catches a handful of bullets and places them inside his mouth; he gnaws on the ammunition and shoots one large shell at the corral.

Just as Injun Joe brandishes a hatchet and bears down on the wagon train, Porky and his horse arrive in the nick of time. Our diminutive hero challenges the towering warrior to a fight, and a deadly chase ensues. Joe whirls his cleaver into a “buzzsaw” action, chiseling mountain formations into the Statue of Liberty and a city skyline, possibly an allusion to the Lenape tribe’s original ownership of “Manhatta,” or Manhattan. (Injun Trouble’s production draft denotes the skyline as one resembling New York City’s though no discernable landmarks appear – Wagon Heels eliminates the city skyline but retains the Statue of Liberty.) Clampett raises the tension in its remake: Injun Joe finds the wagon engineer as his first victim before his confrontation with Porky; our hero now swipes Joe’s weapon and bashes him on the foot—of course, Joe is unmoved by the puny effort.

Now cornered at a cliff top, Porky is captured by Injun Joe, pulling him up by one strand of hair, ready to strike. The precipice in Wagon Heels adds more peril to the film’s climactic moments— Clampett’s background painter (and close collaborator) Mike Sasanoff renders it in an atmospheric haze, accentuating its sheer height. With no time to spare, Goofus/Sloppy Moe intervenes with another taunt, which provokes Injun Joe to grab the crazed pioneer by his long beard, demanding him to reveal his big message. The secret: Injun Joe is ticklish!

Now cornered at a cliff top, Porky is captured by Injun Joe, pulling him up by one strand of hair, ready to strike. The precipice in Wagon Heels adds more peril to the film’s climactic moments— Clampett’s background painter (and close collaborator) Mike Sasanoff renders it in an atmospheric haze, accentuating its sheer height. With no time to spare, Goofus/Sloppy Moe intervenes with another taunt, which provokes Injun Joe to grab the crazed pioneer by his long beard, demanding him to reveal his big message. The secret: Injun Joe is ticklish!

Both versions have Injun Joe incapacitated by being tickled, yet Injun Trouble and Wagon Heels provide starkly different conclusions to their narratives. Goofus incessantly tickles the hulking Joe into submission in Injun Trouble, which lands him inside a hollow tree trunk. The iris comes to a close but suddenly pops back open—Injun Joe asks Goofus to tickle him some more! (Chuck Jones elaborates on Clampett’s suggestive humor by drawing eyelashes on Joe to punctuate this fixation.)

In Wagon Heels, Sloppy Moe’s tickling causes Joe to step back too far from the cliff’s edge. Then, in typical Warners cartoon fashion, Joe stops to look down below before plummeting to earth. The animation of the ground engulfed by the impact of Joe’s crash is rotoscoped from Clampett’s A Tale of Two Kitties (1942) when an anvil lands on Catsello with the same effect. (The “roto” description in Wagon Heels’ sc. 49A suggests the earlier animation was traced off of the film under the camera rather than reusing its original pencil animation.) The conflict now ends in a patriotic coda—the force of Injun Joe’s collapse stretches the United States across the West Coast. Our two brave explorers, Porky and Sloppy Moe, salute underneath a sky shining the emblematic colors of the American flag. Attentive viewers may notice that, in both versions, once Porky dismounts to confront Injun Joe, his horse vanishes from the cartoon!

Injun Trouble had its New York opening in Broadway’s Strand Theater on April 16, 1938, before its announced release nationwide on May 21. A year later, the May 31, 1939 edition of The Exhibitor announced the cartoon as the third-place nominee of the 1939 Grand Shorts Award—first place went to Clampett’s The Lone Stranger and Porky, with Fleischer’s Mutiny Ain’t Nice, with Popeye the Sailor, as second runner-up.

In both interpretations of Clampett’s pioneer picture, Carl Stalling chose the same leitmotifs for each character (and sequence). Stephen Foster’s “Oh Susanna” is inserted into the soundtrack for the traveling wagon train; Porky and his horse are accompanied by Henry C. Work’s “Kingdom Coming (Jubilo)”; “The Old Apple Tree,” the theme for Goofus/Sloppy Moe, was a recent tune from songwriters M. K. Jerome and Jack Scholl for the Warners musical Swing Your Lady, and his obnoxious taunt is done to the tune of “London Bridge;” Stalling uses Leo Friedman’s “Sun Dance,” an “Indian characteristic” placed in several cartoons with Native American themes, for Injun Joe; the battle between Joe and the settlers utilizes George J. Trinkaus’s “Indian Wedding Feast,” a composition designed for silent movies.

In both interpretations of Clampett’s pioneer picture, Carl Stalling chose the same leitmotifs for each character (and sequence). Stephen Foster’s “Oh Susanna” is inserted into the soundtrack for the traveling wagon train; Porky and his horse are accompanied by Henry C. Work’s “Kingdom Coming (Jubilo)”; “The Old Apple Tree,” the theme for Goofus/Sloppy Moe, was a recent tune from songwriters M. K. Jerome and Jack Scholl for the Warners musical Swing Your Lady, and his obnoxious taunt is done to the tune of “London Bridge;” Stalling uses Leo Friedman’s “Sun Dance,” an “Indian characteristic” placed in several cartoons with Native American themes, for Injun Joe; the battle between Joe and the settlers utilizes George J. Trinkaus’s “Indian Wedding Feast,” a composition designed for silent movies.

The orchestral background score for Wagon Heels was recorded on February 13, 1945, ten months after its initial dialogue track session. One subtle difference in Stalling’s score for the remake occurs when the action cross-cuts between Injun Joe and Porky; Stalling intermingles “Indian Wedding Feast” and “Jubilo” before our hero meets the hulking opponent face-to-face. Wagon Heels had its announced release to theaters on July 28, 1945. A month later, on August 27, the Strand Theater also booked the remake—with Warner Bros.’ Pride of the Marines as its feature presentation—where it continued to play throughout September.

Thanks to Jerry Beck, Ruth Clampett, Bob Jaques, Keith Scott, Eric Costello, Daniel Goldmark, and Frank M. Young for the production materials and input used in this post.