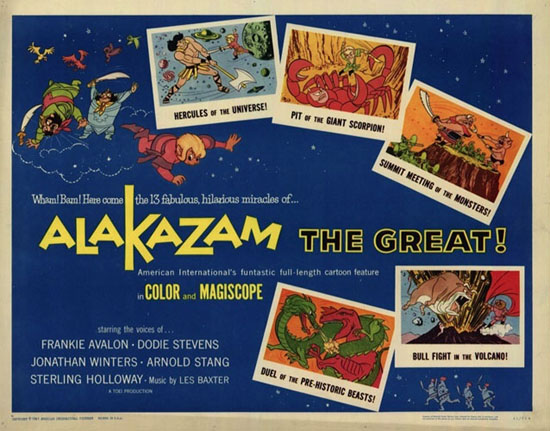

The original star of what would become “anime” in America was a monkey. The year was 1961, the film was called Saiyu-ki, and this is how it came to America as Alakazam the Great.

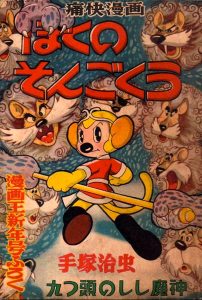

Tezuka’s 1950s manga serialization of Goku the Monkey King

Four hundred years ago, Chinese author Wu Ch’êng-ên wrote the penultimate, hundred-chapter Chinese folk tale Hsi Yu Ki (Record of a Journey to the West). The central figure is a trickster known as Monkey.

The book: Monkey is the king of his kind, but he seeks immortality, which he attains from a mystic sage. Bearing a magic cudgel, Monkey goes on an Earthly rampage, which the Hosts of Heaven stop by giving Monkey a job as the tender of a sacred peach garden. The magic peaches contain godlike powers, and Monkey eats them all.

Monkey declares war on Heaven, challenging the Great Buddha himself to a duel. Monkey loses, earning imprisonment. Freedom comes after Buddha sends the holy priest Tripitaka on a quest to retrieve Buddha’s True Scriptures from India; Monkey is part of a team of reprobates hoping for pardons by protecting Tripitaka on his danger-filled journey to the West. Pigsy, a carouser, and Sandy, who shattered a holy dish, are the other hopefuls. Many fantastic adventures ensue.

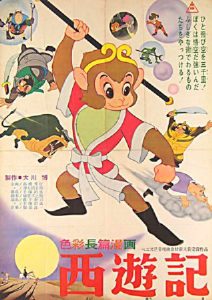

Toei Animations came about in 1956. Its third project was an adaptation of “Journey to the West,” written by the future anime great Osamu Tezuka. He was to write the screenplay, assisted by Hideyuki Takahashi and Goro Kontaibo. Tekuza also co-directed with Daisaku Shirakawa and Taiji Yabushita. Tekuza had never directed or written a script and needed help. The film, also known as The Enchanted Monkey, premiered in 1960 to widespread acclaim. Enter American International Pictures with an offer to bring the picture to America. AIP specialized in importing foreign cheapies.

Toei Animations came about in 1956. Its third project was an adaptation of “Journey to the West,” written by the future anime great Osamu Tezuka. He was to write the screenplay, assisted by Hideyuki Takahashi and Goro Kontaibo. Tekuza also co-directed with Daisaku Shirakawa and Taiji Yabushita. Tekuza had never directed or written a script and needed help. The film, also known as The Enchanted Monkey, premiered in 1960 to widespread acclaim. Enter American International Pictures with an offer to bring the picture to America. AIP specialized in importing foreign cheapies.

Toei gave AIP good material. The first third of the film is faithful to the original text. Tezuka made some original tweaks, such as providing Monkey with a girlfriend, DeDe, who serves as his conscience. Tezuka compresses some adventures into a battle between our heroes and a bull demon (called King Gruesome in the US version). They triumph, and Monkey returns a hero, marrying DeDe. Thus ends the Japanese version.

(Note: Upon Monkey’s return, DeDe is bedridden and gravely ill, watched over by three concerned monkey doctors. When Monkey appears, she instantly revives. This scene is a direct homage to the 1941 Fleischer two-reel feature, “Raggedy Ann and Andy,” right down to the three doctors. Tezuka was an avid fan of the Fleischer cartoons).

Jonathan Winters and Arnold Stang pose for a publicity image from ALAKAZAM THE GREAT

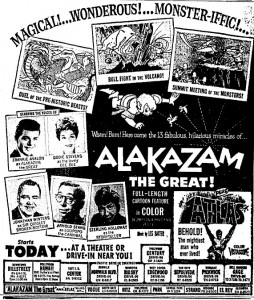

AIP marketed its dismal imports to teen audiences, so teen idols Frankie Avalon and Dodie Stevens were cast as Alakazam and DeDe. Jonathan Winters voiced Pigsy, and Arnold Stang played Sandy (now called Lulipopo). Sterling Holloway narrated the film. Lee Baxter provided four musical numbers. Since the film told a religious and spiritual story from the Buddhist faith that US kids would not understand, much of the dialogue was altered or cut.

Kresel and Rusoff manhandled Tezuka’s film, changing Heaven to “Majutsoland,” home of magicians. Buddha was now “King Amo,” his sister Kuan-yi became “Queen Amas,” and the priest Tripitika” was now their royal son “Prince Amo.” The journey was mistranslated into a pilgrimage to prepare Prince Amo for the throne. Patriarch Subboti, the sage who first taught Monkey magic, is now called “Merlin the Magician,” which is probably the only master magician Rusoff and Kresel thought US kids would recognize. Heaven’s enforcer, Erh-lang, who tried to stop Monkey’s rampage, was changed to “Hercules” (see above explanation).

More mangling of the original film: When Monkey confronts the Great Buddha, it is now a fight between Monkey and King Amo. There is no hint that the contest was to determine who would rule as God. The extent of Monkey’s blasphemy is now lost on the audience. Sandy, a river-dwelling spirit that consumes human flesh, was depicted as a stereotypical African cannibal because that was easiest for Rusoff and Kresel to adapt.

More mangling of the original film: When Monkey confronts the Great Buddha, it is now a fight between Monkey and King Amo. There is no hint that the contest was to determine who would rule as God. The extent of Monkey’s blasphemy is now lost on the audience. Sandy, a river-dwelling spirit that consumes human flesh, was depicted as a stereotypical African cannibal because that was easiest for Rusoff and Kresel to adapt.

Wretched dubbing and dialogue run rampant. Alakazam’s challenge to King Amo includes, “You get me, buddy?” Faced with the heavenly enforcer, the monkey taunts: “I’ll call you Jerk-ules!” Merlin retired because “the wizard field is too crowded,” and King Gruesome’s wife whines seductively for a mink coat. Otaku could not have been pleased.

Les Baxter’s four songs are possibly the worst of his storied career, and the editing by Salvatore Billiteri is choppy and obvious. Considering what the film went through in AIP’s hands, it was a thankless job at the start. The film premiered on July 14, 1961.

Much of the animation is solid, expressive, and quite good. Multiplane sequences and reflections in water and on polished floors are present. There is seamless morphing, without the use of CGI, in the battle between Monkey and Hercules, and some highly naturalistic backgrounds are rendered in a watercolor style. A digital restoration would greatly benefit this film.

Saiyu-ki, in its original form, was a good film that suffered from bad luck; it was adapted for American audiences by a distributor of exploitation films during a time when anime’s authenticity counted for little if anything at all.

Here is a seven minute Japanese language theatrical featurette with some behind the scenes footage of Saiyu-ki, with animators, voice actors and artists:

Here is the complete, Cinemascope (wide screen), Japanese version of Saiyu-ki (with English sub-titles):

• This article is a condensation of an piece I originally wrote for TOON Magazine in issue #22, Summer 2000.