Today’s line-up takes us from 1932 into mid-1937. It’s almost a little surprising that there weren’t more appearances of baseball in cartoons during this period. Some studios (such as Fleischer) seem to have avoided delving into it for many years. Even Disney in the sound era oddly never found an opportunity for Mickey Mouse to play baseball – though he would be triple-threat at football, polo, and Olympic events). Nevertheless, every so often, the sport would be remembered for a subject, and its appearances in animation would begin to increase toward the later part of the decade and into the ‘40’s. There is also not that much name-dropping or caricature during this period to reference real-life ball players, with the exception, of course, of two impersonations of the home run king, in intimidating fashion.

The Ball Game (Van Beuren/Pathe, Aesop’s Fables, 7/30/32 – John Foster/George Rufle, dir.) – A pretty commonplace Aesop’s installment – one of the first I was ever exposed to via PBS’s “Matinee at the Bijou”, where it failed to impress. The usual parade to the staduim (set to the recent Warner hit, “I Love a Parade”, marginally included in only the credits of Winnie Lightner’s “Manhattan Parade”) announces a baseball match-up between the Big Bugs and the Little Bugs. All variety of large insects populate the former team, while the latter seems to consist of a swarm of identical-looking flies. Insects travel to the event via trolley cars, but some depend on their own transportation, the right field bleachers filling by a fly-in of insects in a swarm cloud. Old habits die hard, and the first two pitches of the game are again “Heeza Liar” zig-zag curves, brought on by the pitcher spiraling his fingers around the ball as in Van Beuren’s earlier production, “Play Ball”. The third pitch results in a hit. A long-nosed mosquito waits in the outfield to make the catch, bit has the ball get skewered directly upon his nose. Another fielder tries to pry it off, but no use. So, the second fielder grabs the feet of the mosquito, swings him around in a circle, then flings him bodily toward home plate. A race for the plate ensues between the running fly batter and the mosquito soaring in air behind him, and the mosquito scores a sting upon the fly’s rear end, accomplishing a tag at the same time, for an out at the plate.

The Ball Game (Van Beuren/Pathe, Aesop’s Fables, 7/30/32 – John Foster/George Rufle, dir.) – A pretty commonplace Aesop’s installment – one of the first I was ever exposed to via PBS’s “Matinee at the Bijou”, where it failed to impress. The usual parade to the staduim (set to the recent Warner hit, “I Love a Parade”, marginally included in only the credits of Winnie Lightner’s “Manhattan Parade”) announces a baseball match-up between the Big Bugs and the Little Bugs. All variety of large insects populate the former team, while the latter seems to consist of a swarm of identical-looking flies. Insects travel to the event via trolley cars, but some depend on their own transportation, the right field bleachers filling by a fly-in of insects in a swarm cloud. Old habits die hard, and the first two pitches of the game are again “Heeza Liar” zig-zag curves, brought on by the pitcher spiraling his fingers around the ball as in Van Beuren’s earlier production, “Play Ball”. The third pitch results in a hit. A long-nosed mosquito waits in the outfield to make the catch, bit has the ball get skewered directly upon his nose. Another fielder tries to pry it off, but no use. So, the second fielder grabs the feet of the mosquito, swings him around in a circle, then flings him bodily toward home plate. A race for the plate ensues between the running fly batter and the mosquito soaring in air behind him, and the mosquito scores a sting upon the fly’s rear end, accomplishing a tag at the same time, for an out at the plate.

The sides change. A centipede is next at bat – with five bats to swing. Four of them miss another wildly-curving ball, but the fifth bat connects – without the other four swings being counted as strikes. He passes first base, but gets caught up between first and second by two fly basemen. After some back-and-forth tosses, the centipede escapes the trap in his own unique way – by separating into segments, which scatter to run in helter-skelter directions all over the place, confusing the basemen and leaving them slightly dizzy, while all the segments wend their way to second base and reassemble as the centipede. The frustrated first baseman kicks the second baseman in the rear for his incompetence.

A winged beetle, the power-hitter of the big bugs (with a build and face resembling Babe Ruth), steps up to the plate. A couple of the usual curve balls, and there are two strikes on the batter. Then, the batter reveals his additional secret weapons – six arms under his wings, loaded with bats. The pitcher begins to sweat, and whistles to the field for his teammates to join him on the mound. With that many arms to pitch to, the entire team begins throwing baseballs at the mound, all at once. The batter is like a well-oiled machine, and begins socking hits into the field, three at a time, over and over again, not letting a ball go by. The flies desperately spread out over the field, but trying to catch up with all the balls landing on the green is more than they can handle, and soon the only contact they are making with the balls is to get clobbered by them as they fall from the sky like rain. The batter finally tires of swinging, and begins a slow, confident trot around the bases, doffing his cap right and left to acknowledge the cheers of the crowd. All the balls finally conclude landing in the field, and the flies frantically start picking them up in every direction, flinging them back toward the advancing runner. The beetle has his victory lap spoiled by being conked in the head by a first ball, knocking him down. Another hits him, then another, then another. We’ll never know how the play is being scored, because the rest of the balls start raining down upon the grandstand. The throws from the field are endless, and in a pair of repeated cycles of animation that look primitive enough to have been lifted from a Terry Aesop from 1923 (and for all we know, might have been at that), the spectators exit the stadium in panicked droves, amidst the continuing deluge of baseballs, for the iris out.

A winged beetle, the power-hitter of the big bugs (with a build and face resembling Babe Ruth), steps up to the plate. A couple of the usual curve balls, and there are two strikes on the batter. Then, the batter reveals his additional secret weapons – six arms under his wings, loaded with bats. The pitcher begins to sweat, and whistles to the field for his teammates to join him on the mound. With that many arms to pitch to, the entire team begins throwing baseballs at the mound, all at once. The batter is like a well-oiled machine, and begins socking hits into the field, three at a time, over and over again, not letting a ball go by. The flies desperately spread out over the field, but trying to catch up with all the balls landing on the green is more than they can handle, and soon the only contact they are making with the balls is to get clobbered by them as they fall from the sky like rain. The batter finally tires of swinging, and begins a slow, confident trot around the bases, doffing his cap right and left to acknowledge the cheers of the crowd. All the balls finally conclude landing in the field, and the flies frantically start picking them up in every direction, flinging them back toward the advancing runner. The beetle has his victory lap spoiled by being conked in the head by a first ball, knocking him down. Another hits him, then another, then another. We’ll never know how the play is being scored, because the rest of the balls start raining down upon the grandstand. The throws from the field are endless, and in a pair of repeated cycles of animation that look primitive enough to have been lifted from a Terry Aesop from 1923 (and for all we know, might have been at that), the spectators exit the stadium in panicked droves, amidst the continuing deluge of baseballs, for the iris out.

Play Ball (Ub Iwerks/MGM. Willie Whopper, 9/16/33) – The first publicly-exhibited Wille cartoon, and a quite good one, finds out hero at a carnival “African Dodger” booth, pitching baseballs at a quartet of black stereotype folks who peer over a fence partition, jeering customers to take their best shots at trying to bean them. Willie’s marksmanship is infallible, conking three of the quartet. The next pitch passes the fourth, who already has one lump on his head from Willie’s past throws. The black sticks out his tongue to taunt Willie at missing him, but Willie’s baseball takes note of it, stops in mid-air, and reverses direction, smacking the black in the head from the opposite side. Now with two lumps on his head, the black makes things right for himself again, by yanking on his ears, causing both lumps to retract into his skull. Willie finishes off his throwing exhibition with a shot that destroys the fence partition, piling up the fence lumber in a neat stack atop the heads of all four blacks.

Play Ball (Ub Iwerks/MGM. Willie Whopper, 9/16/33) – The first publicly-exhibited Wille cartoon, and a quite good one, finds out hero at a carnival “African Dodger” booth, pitching baseballs at a quartet of black stereotype folks who peer over a fence partition, jeering customers to take their best shots at trying to bean them. Willie’s marksmanship is infallible, conking three of the quartet. The next pitch passes the fourth, who already has one lump on his head from Willie’s past throws. The black sticks out his tongue to taunt Willie at missing him, but Willie’s baseball takes note of it, stops in mid-air, and reverses direction, smacking the black in the head from the opposite side. Now with two lumps on his head, the black makes things right for himself again, by yanking on his ears, causing both lumps to retract into his skull. Willie finishes off his throwing exhibition with a shot that destroys the fence partition, piling up the fence lumber in a neat stack atop the heads of all four blacks.

Willie’s sweetie (did she ever have a name?), a female character designed by Grim Natwick, applauds Willie, and takes his arm for a stroll further down the road, past the back fence of a baseball stadium. Two youths are taking turns pushing each other out of the way to peer through a fence knothole, but utter remarks at each other that are exceedingly polite, almost reminding one of the type of dialogue that might in later years have befit the Goofy Gophers. Wille intervenes to settles the dispute, with a trick that actually makes no practical sense. He grabs a funnel from a nearby trash box, and sticks the small end in the hole. Now, the opposite end is allegedly wide enough that both boys can simultaneously watch through the hole together. Willie himself also watches, as a game takes place within between the Cubs and the Yanks. The Yankees had for quite a few years been well known for a non-stop power lineup that had become nicknamed “Murderer’s Row”. At the head of the pack was the already well-renowned Babe Ruth, who is caricatured throughout this cartoon. Ruth hits a towering home run ball, well past the outfield fence. Seeing the hit through the hole, Willie fades back, back, back, getting himself under the oncoming ball, and catching it bare-handed, as the power of its fall shakes the ground upon which he stands. Triumphant, Willie escorts his girl to the ticket booth of the stadium, where, for returning the ball, he receives two free passes.

From grandstand seats, Willie and his girl enjoy the game and devour peanuts. The Cubs are pitching, and things don’t look good. The Yanks are so anxious to get at the pitcher, they all stand on deck at once, none of them remaining in the dugout. Each one seems to connect with the ball a different way, one of them even letting the ball rebound off his chin. The Cubs’ pitcher even tries a spit ball – but the ball spits back. The tactic proves of no effect, and each contact of the batters leads to another hit, and another run, with 30 runs currently showing on the scoreboard. The crowd begins to chant for the Cubs’ manager to take the pitcher out, and a theatrical “hook” appears from the sidelines, yanking the pitcher off the mound by the neck. A seconf pitcher comes to the mound, and after facing only one batter, receives the same treatment from the hook. The Cubs’ manager is pacing the dirt and tearing his hair, when he overhears Willie bragging to his girl, “Phooey! I could beat those guys easy. I wish I could pitch this game.” Fed up with such comments, and having nobody better to turn to in his bull pen anyway, the manager yanks Willie from his seat, and hands him a glove. Willie briefly swallows hard and tries to control his knocking knees at being called to make good his boast, but regains his composure, snapping his fingers to indicate the situation is under control, and marches out to the mound.

From grandstand seats, Willie and his girl enjoy the game and devour peanuts. The Cubs are pitching, and things don’t look good. The Yanks are so anxious to get at the pitcher, they all stand on deck at once, none of them remaining in the dugout. Each one seems to connect with the ball a different way, one of them even letting the ball rebound off his chin. The Cubs’ pitcher even tries a spit ball – but the ball spits back. The tactic proves of no effect, and each contact of the batters leads to another hit, and another run, with 30 runs currently showing on the scoreboard. The crowd begins to chant for the Cubs’ manager to take the pitcher out, and a theatrical “hook” appears from the sidelines, yanking the pitcher off the mound by the neck. A seconf pitcher comes to the mound, and after facing only one batter, receives the same treatment from the hook. The Cubs’ manager is pacing the dirt and tearing his hair, when he overhears Willie bragging to his girl, “Phooey! I could beat those guys easy. I wish I could pitch this game.” Fed up with such comments, and having nobody better to turn to in his bull pen anyway, the manager yanks Willie from his seat, and hands him a glove. Willie briefly swallows hard and tries to control his knocking knees at being called to make good his boast, but regains his composure, snapping his fingers to indicate the situation is under control, and marches out to the mound.

Willie’s first pitch is forcefully hit, as a rising pop fly, which doesn’t seem to have any intention of coming down. Willie addresses this problem by producing from his pocket a slingshot. He takes dead aim at the ball, and fires a stone. The stone makes a direct hit on the ball, ceasing its flight like a wounded bird, and causing the ball to plummet, straight into Willie’s waiting hat. The next batter also takes a sock at the ball, tearing its cover off. Cover flies in one direction, while the twine center of the ball unravels into a long thin thread in the air nearby. Willie runs unto the field with his glove. He gets under the torn cover, catching it in a position where the ball reassembles as if a hollow cup with the top-half flipped open like a cap. Willie slightly repositions, and catches within the ball cup one end of the twine thread, which conveniently accumulates within the cup, resuming and spiraling into its original round shape, so that, when the cup is full of the complete ball of twine, the cloth cap snaps shut upon it, restoring the orb to its original baseball form.

But the third batter of the inning may not prove so east. Ruth! Willie again swallows hard, and this time, he means it. But he knuckles down with a look of determination, and removes his coat, reducing his outfit to shirtsleeves, to be sure he is loose enough to give this powerhouse his best shots. Willie’s first throw is a fireball – literally, setting fire to the catcher’s mitt, which he is forced to douse in a bucket of water. The second pitch again whizzes past Ruth, striking the umpire in the chest protector and knocking him down. The protector sprouts four protruding springs from the damage, just like the insides of an old mattress. Now Willie needs that final strike. Ruth now holds three bats at once, and finally connects. The ball sails like a bullet through the air, spinning rapidly as it goes. It passes between the legs of a stray bird flying over the field, causing the bird to laugh hysterically as the ball passes under its – you know. Willie takes off in a dead run toward the fence, but does not give up when he reaches it. Hopping over the fence, Willie lands in an old flivver parked in the parking lot. Turning the key, he takes off with the car after the ball. Looking back over his shoulder to see the ball’s progress, Willie fails to watch the road, and collides with an oriental laundry man carrying a basket of clothes upon his head. The clothes fly everywhere, and, in a gag reported by Steve Stanchfield to have been edited before release of the film for censorship reasons, but which a close examination of remaining frames hints at, the car apparently appears, dressed in women’s underwear.

But the third batter of the inning may not prove so east. Ruth! Willie again swallows hard, and this time, he means it. But he knuckles down with a look of determination, and removes his coat, reducing his outfit to shirtsleeves, to be sure he is loose enough to give this powerhouse his best shots. Willie’s first throw is a fireball – literally, setting fire to the catcher’s mitt, which he is forced to douse in a bucket of water. The second pitch again whizzes past Ruth, striking the umpire in the chest protector and knocking him down. The protector sprouts four protruding springs from the damage, just like the insides of an old mattress. Now Willie needs that final strike. Ruth now holds three bats at once, and finally connects. The ball sails like a bullet through the air, spinning rapidly as it goes. It passes between the legs of a stray bird flying over the field, causing the bird to laugh hysterically as the ball passes under its – you know. Willie takes off in a dead run toward the fence, but does not give up when he reaches it. Hopping over the fence, Willie lands in an old flivver parked in the parking lot. Turning the key, he takes off with the car after the ball. Looking back over his shoulder to see the ball’s progress, Willie fails to watch the road, and collides with an oriental laundry man carrying a basket of clothes upon his head. The clothes fly everywhere, and, in a gag reported by Steve Stanchfield to have been edited before release of the film for censorship reasons, but which a close examination of remaining frames hints at, the car apparently appears, dressed in women’s underwear.

Still proceeding ahead while looking behind him, Willie drives the car off a pier into New York harbor. Willie rises from the waves, and happens to find an unmanned motorboat near the dock. Revving up the outboard motor, Willie is off again in quest of the ball, which itself is now passing over the harbor. Willie approaches the Statue of Liberty (which just happens to be carrying in her hand a large mug of beer instead of her torch, in celebration of the repeal of prohibition). Wille calls out a request for assistance to the statue, which in response comes to life, leaps high off her pedestal, and catches the ball in her mug. She pours out the ball to Willie, who must now figure out how to field it, as Ruth, back in the park, is continuing to round the bases. (There is a question why the catch of the ball did not result in an automatic out – but then, I guess Lady Liberty wasn’t officially on the team, so her contact with the ball probably only counts as if part of the field.) Willie spots a cannon at one end of the statue’s island, pointing in the right direction. Dropping the ball in the cannons mouth, Willie ignites a fuse, then leaps inside to join the ball as the cannon fires. Both he and the sphere fly miles and miles back to the stadium, and land directly in front of the Babe just before he can reach home. The out is recorded, and all Babe can say is “Darn.” The film ends with a process shot of a New York ticker tape parade, with Willie, his girl, and the Cubs manager riding in a limousine as the persons of honor. (Now why would New Yorkers honor Willie for defeating their home team? Maybe the game should have been set in Chicago. And don’t ask how Willie scored those 31 runs, since we never even saw him at bat!)

Still proceeding ahead while looking behind him, Willie drives the car off a pier into New York harbor. Willie rises from the waves, and happens to find an unmanned motorboat near the dock. Revving up the outboard motor, Willie is off again in quest of the ball, which itself is now passing over the harbor. Willie approaches the Statue of Liberty (which just happens to be carrying in her hand a large mug of beer instead of her torch, in celebration of the repeal of prohibition). Wille calls out a request for assistance to the statue, which in response comes to life, leaps high off her pedestal, and catches the ball in her mug. She pours out the ball to Willie, who must now figure out how to field it, as Ruth, back in the park, is continuing to round the bases. (There is a question why the catch of the ball did not result in an automatic out – but then, I guess Lady Liberty wasn’t officially on the team, so her contact with the ball probably only counts as if part of the field.) Willie spots a cannon at one end of the statue’s island, pointing in the right direction. Dropping the ball in the cannons mouth, Willie ignites a fuse, then leaps inside to join the ball as the cannon fires. Both he and the sphere fly miles and miles back to the stadium, and land directly in front of the Babe just before he can reach home. The out is recorded, and all Babe can say is “Darn.” The film ends with a process shot of a New York ticker tape parade, with Willie, his girl, and the Cubs manager riding in a limousine as the persons of honor. (Now why would New Yorkers honor Willie for defeating their home team? Maybe the game should have been set in Chicago. And don’t ask how Willie scored those 31 runs, since we never even saw him at bat!)

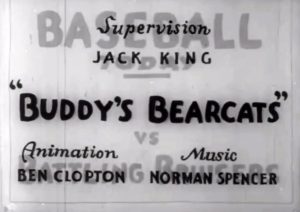

Buddy’s Bearcats (Warner, Buddy, 6/23/34 – Jack King, dir.) – Buddy’s Bearcats vs, the Battling Bruisers. A fat man is stopped after purchasing a ticket at the gate, as the ticket taker measures his girth with a tape measure, then declares that he must pay for two seats. The usual denizens are meanwhile trying to see the game for free. Two kids struggle in vertically positioning two fence posts that seem to be somehow interconnected below ground – when one yanks to bring a knothole down to his eye level, the other’s board shifts its knothole upwards beyond the eye-reach of the other. Another fan gets over the fence free by using the middle section of a dachshund to raise him to the top of the fence like an auto jack, allowing his to climb over. A pair of thrifty Scotsmen appear, one playing a bagpipe, the other a snare drum. The bagpiper inflates his air bag like a balloon, while the drummer attaches the bag to the drum with the straps from the drum’s side. The two then climb upon the drum, using it as a balloon gondola, and sail over the fence to choice seats.

Buddy’s Bearcats (Warner, Buddy, 6/23/34 – Jack King, dir.) – Buddy’s Bearcats vs, the Battling Bruisers. A fat man is stopped after purchasing a ticket at the gate, as the ticket taker measures his girth with a tape measure, then declares that he must pay for two seats. The usual denizens are meanwhile trying to see the game for free. Two kids struggle in vertically positioning two fence posts that seem to be somehow interconnected below ground – when one yanks to bring a knothole down to his eye level, the other’s board shifts its knothole upwards beyond the eye-reach of the other. Another fan gets over the fence free by using the middle section of a dachshund to raise him to the top of the fence like an auto jack, allowing his to climb over. A pair of thrifty Scotsmen appear, one playing a bagpipe, the other a snare drum. The bagpiper inflates his air bag like a balloon, while the drummer attaches the bag to the drum with the straps from the drum’s side. The two then climb upon the drum, using it as a balloon gondola, and sail over the fence to choice seats.

Over a full minute of film is wasted on some unnecessary song and dance, including pitcher Buddy tossing the ball upon a row of bats on the ground to produce xylophone notes, singing hot dog and soda pop vendors, and a singing umpire introducing the two teams. An amazingly-convincing vocal impersonation of Joe E. Brown, who was well-known for his love of the game, and featured such interest as the theme of two of his most successful features around this period. “Elmer the Great” and “Alibi Ike”, provides the play-by-play. No vocal credit for the role appears on IMDB – could it be possible that Brown himself provided the voice just for fun? (Inexplicably, one later shot has Brown talking in an entirely-different voice that sounds nowhere close – also suggesting that Brown himself may have provided the other voicing, and was unavailable for a later revision of a scene.) Buddy uses the familiar zig-zagging curve, and a ball is hit to the announcer’s booth. “Foul ball!”, shouts Brown – and with his large mouth open, swallows the ball. “Shucks, I’m all balled up”, remarks Brown, as the scene wipes to Buddy at bat.

The pitcher facing Buddy has his own idea about lubricating the ball – keeping an oil can for just such purpose concealed in a slot in the ground next to the pitcher’s mound. The catcher sends the pitcher signals by means of a semaphore flag-waving bird perched on his head inside of his catcher’s mask – which serves a dual purpose as a bird cage for the avian. Buddy still gets a hit on the zig-zagging ball, and rolls into first base, via a roller skate strapped to his back.

The pitcher facing Buddy has his own idea about lubricating the ball – keeping an oil can for just such purpose concealed in a slot in the ground next to the pitcher’s mound. The catcher sends the pitcher signals by means of a semaphore flag-waving bird perched on his head inside of his catcher’s mask – which serves a dual purpose as a bird cage for the avian. Buddy still gets a hit on the zig-zagging ball, and rolls into first base, via a roller skate strapped to his back.

We never see if Buddy actually scores, nor follow any of his teammates at bat. Instead, we find ourselves in the next inning, with Buddy pitching again. Buddy tries another wild curve ball, this time via a ball with some unknown gyroscopic mechanical insert, activated by wind-up with a key. The ball takes a complete spiral around the pitcher’s mound, then zigs its way toward the plate. It behaves so much like a darting insect, the batter resorts to a Flit gun to spray the ball and bring it down, then picks up the lifeless ball from the dirt, and socks it into the field. Buddy makes a quick catch for the out, using a telephone extender built into his mitt to make the high-altitude catch from his position below. Score mounts to 47 to 47 – and the writers get stuck for an ending, on this already comparatively weak cartoon. Inconsistently with his behavior throughout the rest of the picture, Buddy is now found hiding in the dugout, afraid to take his at bat despite cheers of his name from the crowd, and has to be coaxed to come out by Cookie. Without any gag to lead into it, Buddy simply knocks a home run into the camera lens, and hats tossed by the cheering crowd pile high on Buddy and Cookie’s heads at home plate, for the iris out.

• A funky upload of BUDDY’S BEARCATS can be seen on DailyMotion.

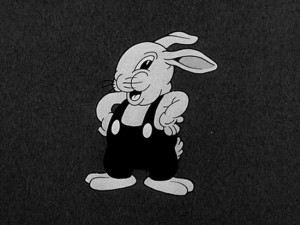

The Tortoise and the Hare (Disney, Silly Symphonies, 1/5/35 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.) is the well-known Oscar winner about the foot race between Toby Tortoise and Max Hare. However, midway in the film, it has a baseball interlude. While attempting to impres the students of Miss Cottontail’s Girls’ School with his speed, Max engages in a single-handed exhibition of multiple sports for the flirtatious rabbits, including baseball. Picking up a mitt and glove from the athletic field, Max takes the mound, and hurls a wind-up pitch toward the empty home plate. He outraces the pitch to the plate, and tosses his mitt high into the air, taking up instead a bat laying in the batter’s box. He connects with a mighty swing, then drops the bat, raising one hand high to allow the now-falling glove to neatly slide on down to his wrist. He then speeds into the outfield, again outracing the ball, and neatly catches his own hit, giving himself a “heave-ho” umpire’s gesture with one hand to declare himself out.

The Tortoise and the Hare (Disney, Silly Symphonies, 1/5/35 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.) is the well-known Oscar winner about the foot race between Toby Tortoise and Max Hare. However, midway in the film, it has a baseball interlude. While attempting to impres the students of Miss Cottontail’s Girls’ School with his speed, Max engages in a single-handed exhibition of multiple sports for the flirtatious rabbits, including baseball. Picking up a mitt and glove from the athletic field, Max takes the mound, and hurls a wind-up pitch toward the empty home plate. He outraces the pitch to the plate, and tosses his mitt high into the air, taking up instead a bat laying in the batter’s box. He connects with a mighty swing, then drops the bat, raising one hand high to allow the now-falling glove to neatly slide on down to his wrist. He then speeds into the outfield, again outracing the ball, and neatly catches his own hit, giving himself a “heave-ho” umpire’s gesture with one hand to declare himself out.

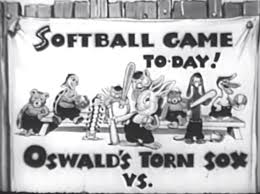

Soft Ball Game (Lantz/Universal, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, 1/27/36) – The only cartoon to my knowledge to refer to the sport of soft ball rather than overhand-pitch baseball. A creative cartoon, filled with almost all original gags. As will be seen below, it was obviously noted by Warner Brothers, who stole gag after gag from it in a subsequent production. It’s Oswald’s Torn Sox vs. the Jungle Giants. We begin the film in the final inning, watching an elephant hit a grand slam, and the scoreboard rack up a tally of 69 to 0. A kangaroo batter lets her Joey do the slugging for her, sailing one into the outfield. A nearsighted mole plays it close to the fence, allowing the ball to merely fall upon his head and bounce to the ground. Dazed and still badly-sighted, he picks up the ball and throws it at the fence instead of back to the infield. Finally, he gets turned around the proper way, and throws it in. A turtle catcher waits for the throw – but the ball runs out of steam just ahead of the plate, and drops dead to the ground, out of the turtle’s reach, as the Joey touches the plate and hops back into his mother’s pouch. Oswald signals angrily to his catcher to come over for a meeting, but in fact does not chastize the catcher, instead whispering strategy to him, to which the turtle nods. Returning to home, the turtle waits, as a powerful gorilla enters the batter’s box. The turtle points to his glove and winks to Oswald, as a hatch opens in the center-padding of the glove, revealing a hidden message concealed within it, reading :”fast ball”.

Soft Ball Game (Lantz/Universal, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, 1/27/36) – The only cartoon to my knowledge to refer to the sport of soft ball rather than overhand-pitch baseball. A creative cartoon, filled with almost all original gags. As will be seen below, it was obviously noted by Warner Brothers, who stole gag after gag from it in a subsequent production. It’s Oswald’s Torn Sox vs. the Jungle Giants. We begin the film in the final inning, watching an elephant hit a grand slam, and the scoreboard rack up a tally of 69 to 0. A kangaroo batter lets her Joey do the slugging for her, sailing one into the outfield. A nearsighted mole plays it close to the fence, allowing the ball to merely fall upon his head and bounce to the ground. Dazed and still badly-sighted, he picks up the ball and throws it at the fence instead of back to the infield. Finally, he gets turned around the proper way, and throws it in. A turtle catcher waits for the throw – but the ball runs out of steam just ahead of the plate, and drops dead to the ground, out of the turtle’s reach, as the Joey touches the plate and hops back into his mother’s pouch. Oswald signals angrily to his catcher to come over for a meeting, but in fact does not chastize the catcher, instead whispering strategy to him, to which the turtle nods. Returning to home, the turtle waits, as a powerful gorilla enters the batter’s box. The turtle points to his glove and winks to Oswald, as a hatch opens in the center-padding of the glove, revealing a hidden message concealed within it, reading :”fast ball”.

Ozzie delivers, and the impact of the throw knocks the catcher to the backstop. Needing further cushioning, the catcher turns his turtle shell around to cover his front like a chest protector. He uses the signal-glove again, calling for a screw ball. Ozzie’s pitch performs a spiral like the threads of a screw, and fools the batter again. But the gorilla isn’t out yet, and knows it. He signals to three of his teammates, who lug in a piece of lumber about six times larger than a regulation bat. Ozzie senses trouble, and signals the infield and outfield to play back for a long hit. The pitch – and, with a child-like mischievous grin, the gorilla fools everybody, by holding his bat out motionless, performing a perfect bunt that dies in momentum a mere few inches ahead of the plate. Oswald and his team scramble for the plate in desperate attempt to reach the ball (what happened to the turtle at home?), and all jump upon it simultaneously, losing track of what they are looking for in a massive dust cloud, while the gorilla rounds the bases and tags up at the plate before any of the team can find the ball. The Giants’ final batter is an elephant of enormous girth. The catcher can’t even see the oncoming ball from around his legs, so has to dart around them to a position under the elephant’s protruding belly to catch the ball. The elephant takes offense at this, and two times removes the catcher from in front of him, placing him back behind his legs with his trunk. The third time, the elephant performs an underhand swing, smacking both turtle and ball for a line drive. The turtle hits the top of the left field flagpole, and is rebounded back the other way by the bending pole. He lands squarely on home plate, and tags the plate with the ball before the elephant can slide in, achieving the third out. Score: 75 to nothing – what the field announcer refers to as a close game.

Ozzie delivers, and the impact of the throw knocks the catcher to the backstop. Needing further cushioning, the catcher turns his turtle shell around to cover his front like a chest protector. He uses the signal-glove again, calling for a screw ball. Ozzie’s pitch performs a spiral like the threads of a screw, and fools the batter again. But the gorilla isn’t out yet, and knows it. He signals to three of his teammates, who lug in a piece of lumber about six times larger than a regulation bat. Ozzie senses trouble, and signals the infield and outfield to play back for a long hit. The pitch – and, with a child-like mischievous grin, the gorilla fools everybody, by holding his bat out motionless, performing a perfect bunt that dies in momentum a mere few inches ahead of the plate. Oswald and his team scramble for the plate in desperate attempt to reach the ball (what happened to the turtle at home?), and all jump upon it simultaneously, losing track of what they are looking for in a massive dust cloud, while the gorilla rounds the bases and tags up at the plate before any of the team can find the ball. The Giants’ final batter is an elephant of enormous girth. The catcher can’t even see the oncoming ball from around his legs, so has to dart around them to a position under the elephant’s protruding belly to catch the ball. The elephant takes offense at this, and two times removes the catcher from in front of him, placing him back behind his legs with his trunk. The third time, the elephant performs an underhand swing, smacking both turtle and ball for a line drive. The turtle hits the top of the left field flagpole, and is rebounded back the other way by the bending pole. He lands squarely on home plate, and tags the plate with the ball before the elephant can slide in, achieving the third out. Score: 75 to nothing – what the field announcer refers to as a close game.

The Giants take the field. The gorilla acts as pitcher, and delivers a couple of wild ones to a dachshund batter, who has to bend his midriff into a U to avoid getting struck by the pitches. Finally, the gorilla unloads a straight ball down the pike. The dachshund swings, and borrows a running technique from the gorilla in Terry’s “The Magnetic Bat” – standing with his hind feet on one bag, while extending his front feet and body to the next base before letting go of the base he’s standing upon. By this method, he easily rounds the bases without getting tagged, and scores the Sox’s first run. A porcupine is next. He hits a long one to left field. The kangaroo is knocked down by the ball hitting her in the chest, and her Joey again comes to the rescue by tossing the ball to the infield. The ball lands on the porcupine’s quills, and the third baseman has to pluck the ball off his back as he passes to put it back in play. His toss to home is a bit too late – plus the ball still has stray quills in it, which get stuck painfully in the elephant catcher’s hand. Next batter is a gopher. The gorilla lifts a pitching technique from Terry’s “The Magnetic Bat”, using his long arm to merely deposit the ball into the grip of the waiting elephant’s trunk. Bit the gopher manages to smack the third pitch. He borrows a play from Terry’s “Play Ball”, tunneling into the soil to avoid getting caught between first and second. The whole team seems to have woken up, and in a dissolving montage of shots, closes the gap by raising the score to 75 to 70. Oswald comes to bat – but the Giants pull their pitcher and send in a substitute – a six-armed octopus (his other two arms serving as feet). Oswald receives six underhand pitches back to back, all of which pass him for strikes – and two outs are recorded on one batter. One last hope. Ozzie sends in a pinch hitter worthy of this pitcher – Senty Centipede. As six more balls are pitched together, Senty unleashes six bats – similar to Van Beuren’s “The Ball Game”. He knocks each ball for a home run, then breaks into segments, allowing himself to count as six different runners touching the bags, scoring the needed six runs to win the game.

The Giants take the field. The gorilla acts as pitcher, and delivers a couple of wild ones to a dachshund batter, who has to bend his midriff into a U to avoid getting struck by the pitches. Finally, the gorilla unloads a straight ball down the pike. The dachshund swings, and borrows a running technique from the gorilla in Terry’s “The Magnetic Bat” – standing with his hind feet on one bag, while extending his front feet and body to the next base before letting go of the base he’s standing upon. By this method, he easily rounds the bases without getting tagged, and scores the Sox’s first run. A porcupine is next. He hits a long one to left field. The kangaroo is knocked down by the ball hitting her in the chest, and her Joey again comes to the rescue by tossing the ball to the infield. The ball lands on the porcupine’s quills, and the third baseman has to pluck the ball off his back as he passes to put it back in play. His toss to home is a bit too late – plus the ball still has stray quills in it, which get stuck painfully in the elephant catcher’s hand. Next batter is a gopher. The gorilla lifts a pitching technique from Terry’s “The Magnetic Bat”, using his long arm to merely deposit the ball into the grip of the waiting elephant’s trunk. Bit the gopher manages to smack the third pitch. He borrows a play from Terry’s “Play Ball”, tunneling into the soil to avoid getting caught between first and second. The whole team seems to have woken up, and in a dissolving montage of shots, closes the gap by raising the score to 75 to 70. Oswald comes to bat – but the Giants pull their pitcher and send in a substitute – a six-armed octopus (his other two arms serving as feet). Oswald receives six underhand pitches back to back, all of which pass him for strikes – and two outs are recorded on one batter. One last hope. Ozzie sends in a pinch hitter worthy of this pitcher – Senty Centipede. As six more balls are pitched together, Senty unleashes six bats – similar to Van Beuren’s “The Ball Game”. He knocks each ball for a home run, then breaks into segments, allowing himself to count as six different runners touching the bags, scoring the needed six runs to win the game.

Lantz knew he had a good one here, and spotlighted the making of the film in the behind-the-scenes documentary short, Cartoonland Mysteries. The film also enjoyed a long shelf life in the Castle Films home movie catalog.

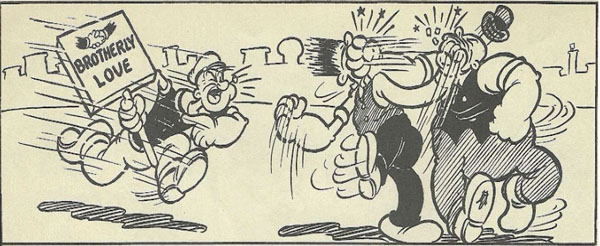

Brotherly Love (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 3/6/36 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Roland Crandall, anim.) – Olive is the president of a Women’s Brotherly Love Society, which is holding a rally and live radio broadcast over station BLAH at Patterson Square Garden. She sings a well0-remembered song, featured in The Popeye Song Folio, about “What we all need is brotherly love.” She specially addresses the radio microphone, to ask, “Are ya’ listenin’. Popeye?” The sailor man is, at a local restaurant, and takes the message to heart. He begins to do random good deeds for everybody, first by heavily over-tipping the waiter. Taking a walk outside, he helps two workers lift a heavy safe to a high office window, and un-wrecks a driver’s automobile. But he also passes the back fence of a local baseball stadium. There, two kids take turns sliding each other out of the way to watch the game through a fence knothole (which for once is not one of those cartoon holes that can be just yanked around in position from board to board). Popeye spots them, and the kids at first try to run, thinking he is the watchman. But Popeye holds them in place by grabbing their belts, and shows them he has good intentions. He takes a sock at a section of the outfield fence. The fence boards shatter and fly high into the air, then come down in the same place, constructing themselves into a small grandstand bleacher seat built just for two. The kids are thus treated to a choice view of the game, as Popeye deposits them in their reserved seats.

The remainder of the film involves Popeye’s problems when he encounters a large group of burly men who do not adhere to Olive’s philosophy. A back street finds the entire membership of two rival clubs headquartered across the street from one another (the Gas House Boys and the Boiler Makers’ Social Club), duking it out in a street brawl. Popeye attempts to verbally intercede, and sings them Olive’s song, but only gets repeatedly bashed for his troubles. Even when he is down, one combatant approaches to hit him with a club, while another rival wants the honors of smacking the sailor. Popeye gentlemanly settles their quarrel by breaking the club in half for each of them, allowing both of them to simultaneously bash him down. Even the arrival of Olive and her society on parade merely results in Olive taking one on the chin, that wraps her around a lamppost. Time for Popeye’s spinach, and he teaches the two clubs some manners – “My way”. Popeye delivers so many blows before the two clubs’ members lay prone in the street, he can’t stop socking, and accidentally delivers another blow to the reviving Olive, who ends the film in Popeye’s arms, but unconscious and with a well-blackened eye.

• You can watch BROTHERLY LOVE on Dailymotion.

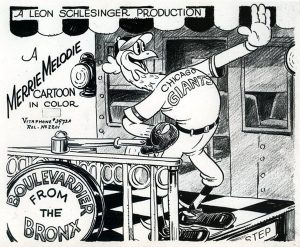

Boulevardier From the Bronx (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 10/10/36 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Another early Warner baseball cartoon, which is again not only exceptionally weak on gags, but engages in outright steals of its best stuff from Lantz’s Soft Ball Game. The rural town of Hickville is to be treated with the honor of an exhibition game against the professional Chicago Giants (interesting, as the Giants in real life had no history in Chicago). Their star pitcher is one Dizzy Dan (a play on words upon the nickname, “Dizzy Dean”, attributed to Jay Hanna Dean, pitcher for the St, Louis Cardinals, Chicago Cubs, and St. Louis Browns, and later a well-regarded sports announcer), a cocky bantam rooster. The train bearing Dan misses the Hickville station by a country mile – so the townfolk push the station platform bodily to meet the train. Dan arrives in a outfit with his name flashing in neon on the back side of his jersey, and spends about a third of the cartoon performing the obligatory plug of the cartoon’s title song. When play finally begins, Dan takes the mound with an attendant at his side, carrying Dan’s arm upon a velvet pillow. A turtle catcher for the Giants turns his shell around to his chest to serve as a chest protector (a direct steal from “Soft Ball Game”). Dan waves to the fielders to go on back into the dugout – he won’t need them, as he intends to strike out the side. The catcher talks up a storm to Dan with fast-chatter encouragement, but keeps getting knocked to the backstop with the force of each caught ball. (The backstop smack is also directly lifted from “Soft Ball Game”. Freleng would also reuse the same fast-talk followed by smack routine for Bugs Bunny in “Baseball Bugs”, after which Chuck Jones would use it in the fight ring for “Rabbit Punch”.) Here, the repeated gag gets a new payoff, as on the third pitch, the catcher replaces his glove with a U-shaped section of stovepipe, allowing the ball to enter one end, then be automatically returned to the pitcher out the other.

Boulevardier From the Bronx (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 10/10/36 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Another early Warner baseball cartoon, which is again not only exceptionally weak on gags, but engages in outright steals of its best stuff from Lantz’s Soft Ball Game. The rural town of Hickville is to be treated with the honor of an exhibition game against the professional Chicago Giants (interesting, as the Giants in real life had no history in Chicago). Their star pitcher is one Dizzy Dan (a play on words upon the nickname, “Dizzy Dean”, attributed to Jay Hanna Dean, pitcher for the St, Louis Cardinals, Chicago Cubs, and St. Louis Browns, and later a well-regarded sports announcer), a cocky bantam rooster. The train bearing Dan misses the Hickville station by a country mile – so the townfolk push the station platform bodily to meet the train. Dan arrives in a outfit with his name flashing in neon on the back side of his jersey, and spends about a third of the cartoon performing the obligatory plug of the cartoon’s title song. When play finally begins, Dan takes the mound with an attendant at his side, carrying Dan’s arm upon a velvet pillow. A turtle catcher for the Giants turns his shell around to his chest to serve as a chest protector (a direct steal from “Soft Ball Game”). Dan waves to the fielders to go on back into the dugout – he won’t need them, as he intends to strike out the side. The catcher talks up a storm to Dan with fast-chatter encouragement, but keeps getting knocked to the backstop with the force of each caught ball. (The backstop smack is also directly lifted from “Soft Ball Game”. Freleng would also reuse the same fast-talk followed by smack routine for Bugs Bunny in “Baseball Bugs”, after which Chuck Jones would use it in the fight ring for “Rabbit Punch”.) Here, the repeated gag gets a new payoff, as on the third pitch, the catcher replaces his glove with a U-shaped section of stovepipe, allowing the ball to enter one end, then be automatically returned to the pitcher out the other.

The home team’s pitcher, a scrawny rooster named Claude, takes the mound. He throws a wild pitch to a dachshund, and the identical gags from “Soft Ball Game” are repeated of the dog bending in a U to avoid getting hit, then rounding the bases with hind feet on one base and front feet on another. A fielding gag is inexplicable, as Claude backs into the field, yelling, “I got it”, but from nowhere, about nine baseballs fall simultaneously, and Claude doesn’t know which to field. Dan comes next to bat, after flirting with Claude’s girlfriend In the stands. Dan lets two pitches sail by. “Ooh, ya better hit it”, calls out the girl. Dan has no worries. “I only need one ball.” He smacks a comebacker into Claude’s chest, knocking him to the outfield fence, where the ball bounces out of Claude’s mitt, uncaught. “Run, run, run”, calls the girl.’ Dan still stands at home plate, resting on his bat, and claims, just as dud Max Hare, that he has “lots of time”. It becomes noticeable at this point that the character concepts for this film are very much an imitation of Max Hare and Toby Tortoise – right down to an irritating bravado laugh from Dan, similar to that of Max.) Claude rises to make a throw to the plate, but only after the ball has left his hand does Dan run – clear round the bases, beating the ball to home, and scoring another run.

The home team’s pitcher, a scrawny rooster named Claude, takes the mound. He throws a wild pitch to a dachshund, and the identical gags from “Soft Ball Game” are repeated of the dog bending in a U to avoid getting hit, then rounding the bases with hind feet on one base and front feet on another. A fielding gag is inexplicable, as Claude backs into the field, yelling, “I got it”, but from nowhere, about nine baseballs fall simultaneously, and Claude doesn’t know which to field. Dan comes next to bat, after flirting with Claude’s girlfriend In the stands. Dan lets two pitches sail by. “Ooh, ya better hit it”, calls out the girl. Dan has no worries. “I only need one ball.” He smacks a comebacker into Claude’s chest, knocking him to the outfield fence, where the ball bounces out of Claude’s mitt, uncaught. “Run, run, run”, calls the girl.’ Dan still stands at home plate, resting on his bat, and claims, just as dud Max Hare, that he has “lots of time”. It becomes noticeable at this point that the character concepts for this film are very much an imitation of Max Hare and Toby Tortoise – right down to an irritating bravado laugh from Dan, similar to that of Max.) Claude rises to make a throw to the plate, but only after the ball has left his hand does Dan run – clear round the bases, beating the ball to home, and scoring another run.

The game moves to the bottom of the ninth, with the Giants ahead 3 to 0. (None of those football or basketball-style scores for this cartoon.) Dan shows off by walking the first three batters, just to get at Claude. His first pitch is a fast one, which almost blows Claude’s feathers off with its passing wind gust. It is followed by a slow ball, which has no new gag whatsoever, and just lopes through the air until reaching the plate, then whooshes by. A final pitch – and again, as with Buddy, the Warner writers can’t come up with any kind of a trick ending. A home run is hit, and as Claude arrives at the plate to score the winning run, he repeats Dan’s irritating laugh in Dan’s face, for the iris out.

• A beautiful print of this cartoon can be seen on Vimeo.

The Twisker Pitcher (Fleischer/Paramount, 5/21/37 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Abner Matthews, anim.) – Popeye’s back, this time as pitcher and manager of Popeye’s Pirates (surprisingly, one of the only animated references to the real-life Pirates franchise, although one might have thought it would have been a natural gag for a nautical epic). Their opponent for today is Bluto’s Bears. Both Bluto and Popeye have their respective girlfriends seated next to one another in reserved boxes as a rooting section. Bluto’s girl looks notably familiar – almost a grown-up version of Harvey Comics’ later “Little Lotta”. (She and Bluto would have made a wonderful couple.) Olive takes it personal whenever the other girl shouts for Bluto, and attempts to silence her by smacking a folding chair over her, trapping her head and arms between the upright panel and seat.

The Twisker Pitcher (Fleischer/Paramount, 5/21/37 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Abner Matthews, anim.) – Popeye’s back, this time as pitcher and manager of Popeye’s Pirates (surprisingly, one of the only animated references to the real-life Pirates franchise, although one might have thought it would have been a natural gag for a nautical epic). Their opponent for today is Bluto’s Bears. Both Bluto and Popeye have their respective girlfriends seated next to one another in reserved boxes as a rooting section. Bluto’s girl looks notably familiar – almost a grown-up version of Harvey Comics’ later “Little Lotta”. (She and Bluto would have made a wonderful couple.) Olive takes it personal whenever the other girl shouts for Bluto, and attempts to silence her by smacking a folding chair over her, trapping her head and arms between the upright panel and seat.

Popeye readies himself to appear on the field in the dressing room, and has to turn back at the last second, realizing he almost left his spinach in his locker. He stands on the mound and bows to the applause of the crowd. Bluto appears from the opposite dugout, joining Popeye on the mound, but extending one arm as he takes his bow, giving himself an excuse to knock Popeye down. As the flustered Popeye leaves to proceed to the batter’s box for the opening pitch of the game, he fails to notice his troublesome spinach can, which falls out from an interior pocket of his uniform. “What a break”, remarks the observant Bluto. Although he has rarely if ever expressed any liking for the stuff, Bluto downs the contents of the spinach can, then decides to really fix Popeye, by plucking at the green of the infield, and filling Popeye’s can with weeds. He then calls out to Popeye that he lost something, and pitches him the refilled can. Popeye is surprised that, thanks to Bluto’s chowing down on Popeye’s greenery, the throw is so forceful as to knock Popeye clear to the backstop. Yet, as Bluto was gracious enough to return the can, Popeye mutters to himself that Bluto isn’t such a bad sport after all.

Popeye readies himself to appear on the field in the dressing room, and has to turn back at the last second, realizing he almost left his spinach in his locker. He stands on the mound and bows to the applause of the crowd. Bluto appears from the opposite dugout, joining Popeye on the mound, but extending one arm as he takes his bow, giving himself an excuse to knock Popeye down. As the flustered Popeye leaves to proceed to the batter’s box for the opening pitch of the game, he fails to notice his troublesome spinach can, which falls out from an interior pocket of his uniform. “What a break”, remarks the observant Bluto. Although he has rarely if ever expressed any liking for the stuff, Bluto downs the contents of the spinach can, then decides to really fix Popeye, by plucking at the green of the infield, and filling Popeye’s can with weeds. He then calls out to Popeye that he lost something, and pitches him the refilled can. Popeye is surprised that, thanks to Bluto’s chowing down on Popeye’s greenery, the throw is so forceful as to knock Popeye clear to the backstop. Yet, as Bluto was gracious enough to return the can, Popeye mutters to himself that Bluto isn’t such a bad sport after all.

The catcher uses again the old gag of signaling to Bluto with semaphore flags. Bluto mutters that he can pitch anything to Popeye, as he’ll never be able to hit it anyway. The first pitch repeats the stock gag of smashing a perfectly circular hole through Popeye’s bat. Popeye adds to the gag with a verbal quip. “A hole in one! I better use a mashie on this one.” The next pitch whizzes by, as Popeye swings so hard, he spins around as if on a pivot, and morphs into a visual gag which Seymour Kneitel would remember to reuse in a 1940’s Screen Song – the swinging of a rusty gate. Bluto states that Popeye will need a telegraph pole to hit the next one, and delivers a pitch only seen as a lightning bolt into the catcher’s mitt. Strike three. Without being seen on screen, Popeye’s next two teammates are similarly brought down in a mere three pitches each, and the side retired.

Popeye and his squad now take the field. As Bluto passes Popeye the ball, he pulls Popeye’s hat down over his eyes. Popeye struggles to remove it, ad-libbing a remark as he wonders if this is night baseball (something relatively new in the leagues at the time, originated in Cincinnatti in 1935). Bluto sends up three of his teammates to get respective singles off of Popeye, loading the bases. Bluto then steps to the plate as clean-up batter. Popeye remarks that he’s behind the 8-ball, and reaches for his spinach reserve – but quickly notices something different about the flavor from the can. His tongue feeling around in the inside of his mouth, Popeye mutters, “This stuff’s been cut.” Bluto’s swing packs a wallop, and he zips around the bags, picking up the three base runners ahead of him as he goes, and carries all of them to a stand-up tag of home plate all at once. Popeye reacts with an Edgar Kenndy slide of his hand down his face in a slow burn, muttering again, “I must be slipping.” 4 runs register on the scoreboard. A time-dissolve shows the score at 21 to 0, with a smaller sign on the board reading “Last Inning”.

Popeye and his squad now take the field. As Bluto passes Popeye the ball, he pulls Popeye’s hat down over his eyes. Popeye struggles to remove it, ad-libbing a remark as he wonders if this is night baseball (something relatively new in the leagues at the time, originated in Cincinnatti in 1935). Bluto sends up three of his teammates to get respective singles off of Popeye, loading the bases. Bluto then steps to the plate as clean-up batter. Popeye remarks that he’s behind the 8-ball, and reaches for his spinach reserve – but quickly notices something different about the flavor from the can. His tongue feeling around in the inside of his mouth, Popeye mutters, “This stuff’s been cut.” Bluto’s swing packs a wallop, and he zips around the bags, picking up the three base runners ahead of him as he goes, and carries all of them to a stand-up tag of home plate all at once. Popeye reacts with an Edgar Kenndy slide of his hand down his face in a slow burn, muttering again, “I must be slipping.” 4 runs register on the scoreboard. A time-dissolve shows the score at 21 to 0, with a smaller sign on the board reading “Last Inning”.

Bluto pitches to Popeye. He begins with a “fade-away” – a ball that literally fades and vanishes from view, yet somehow hits the catcher’s mitt without Popeye ever noticing it. The next pitch is a sinker, which drops at a right angle just before the plate, then zips forward at another right-angle under Popeye’s bat. Then, Bluto’s extra-special screwball. Twisting his arm in a spiral like Popeye’s celebrated twisker punch (how come Popeye doesn’t use this move in a cartoon using “twisker” in the title?), Bluto’s ball reaches the plate, zooms in circles around Popeye from head to foot, and draws a third swing from the sailor, striking him out. The side is apparently out with him, and, under regulation baseball rules, that should be the end of the game – a shutout for Bluto. But, only in a cartoon, the game goes on for the bottom half of the inning. Popeye has his hat pulled down by Bluto again as the pitchers exchange places at the mound, and Popeye plays on words, remarking that he doesn’t like that “underhanded pitcher”. Bluto connects on his first swing, in a shot that more resembles the path of a pinball than a baseball – rebounding off the heads of all eight basemen and fielders, then curving back to the mound to conk Popeye. As Popeye wonders what hit him, he again groggily reaches for his secret weapon. But, knowing the last can didn’t work, he pulls out auxiliary backup – a pouch of spinach seeds. He plants one in the infield grass, then has to wait only a few seconds for a fresh leaf to sprout.

Devouring it, Popeye finally becomes fully charged. He stomps upon the ground, making it shiver, to vibrate the ball from the ground into his mitt. Again ignoring all baseball rules, Bluto doesn’t seem to have budged from home, never seen running the bases after his infield-outfield hit – and yet stands at bat again, with the scoreboard still reading only 21 runs. What happened to his teammates, and to his touching the bags? As Popeye is the only standing player on his side, he doubles as both pitcher and catcher, outracing the pitched ball to the bag to tally two strikes on Bluto. But Bluto clouts the third. Popeye runs to the outfield bleachers, and pushes a multi-tiered section of spectators back about ten feet to make the catch of the fly for the out. “Whaddya mean, out?”, snarls Bluto, who begins grabbing up the day’s supply of baseballs to hurl at Popeye. Popeye catches every one bare-handed on his way back to the mound. Out of balls, Bluto charges the mound, but Popeye grabs the end of Bluto’s bat, judo-flipping him. Popeye leaves the balls on the mound, and darts to home plate. Now, it’s bad enough to hold a bottom-of-the-ninth with the game already won by the home team. But allowing the visitors to come to bat for a second time in the same inning? Come on, now! Bluto starts flinging balls at Popeye non-stop. Popeye socks 21 of them consecutively out of the park, then circles the bases 21 times. Score tied! Bluto, again out of baseballs, charges the plate. “You’re out”, shouts Popeye, smacking Bluto in the jaw with his fist. Bluto sails through the air, striking the scoreboard within Popeye’s score box, and is bent into a shape looking exactly like the number 2 – making the scoreboard read 22 for Popeye’s team. Back at the reserved boxes, Olive now has Bluto’s girl pinned down to the ground in a wrestling hold, and demands to know, “Who’s strong to the ’finich’ ‘cause he eats his spinach?’ The girl responds in humiliation, “Popeye the sailor man.”

Devouring it, Popeye finally becomes fully charged. He stomps upon the ground, making it shiver, to vibrate the ball from the ground into his mitt. Again ignoring all baseball rules, Bluto doesn’t seem to have budged from home, never seen running the bases after his infield-outfield hit – and yet stands at bat again, with the scoreboard still reading only 21 runs. What happened to his teammates, and to his touching the bags? As Popeye is the only standing player on his side, he doubles as both pitcher and catcher, outracing the pitched ball to the bag to tally two strikes on Bluto. But Bluto clouts the third. Popeye runs to the outfield bleachers, and pushes a multi-tiered section of spectators back about ten feet to make the catch of the fly for the out. “Whaddya mean, out?”, snarls Bluto, who begins grabbing up the day’s supply of baseballs to hurl at Popeye. Popeye catches every one bare-handed on his way back to the mound. Out of balls, Bluto charges the mound, but Popeye grabs the end of Bluto’s bat, judo-flipping him. Popeye leaves the balls on the mound, and darts to home plate. Now, it’s bad enough to hold a bottom-of-the-ninth with the game already won by the home team. But allowing the visitors to come to bat for a second time in the same inning? Come on, now! Bluto starts flinging balls at Popeye non-stop. Popeye socks 21 of them consecutively out of the park, then circles the bases 21 times. Score tied! Bluto, again out of baseballs, charges the plate. “You’re out”, shouts Popeye, smacking Bluto in the jaw with his fist. Bluto sails through the air, striking the scoreboard within Popeye’s score box, and is bent into a shape looking exactly like the number 2 – making the scoreboard read 22 for Popeye’s team. Back at the reserved boxes, Olive now has Bluto’s girl pinned down to the ground in a wrestling hold, and demands to know, “Who’s strong to the ’finich’ ‘cause he eats his spinach?’ The girl responds in humiliation, “Popeye the sailor man.”

• THE TWISKER PITCHER is on DailyMotion.

NEXT WEEK: Paul Terry gets back into the act, and Warner starts getting more clever with incidental gags, as we move into the late ‘30’s and early ‘40’s, next time.