In 1973 Scatman Crothers experienced a transition in his career as a vocal artist in animation, leaving behind an old character and voicing a new one. But both the old and new roles had one thing in common: Harlem, New York. Since 1970, Crothers had voiced the caricature of basketball player Meadowlark Lemon for Hanna-Barbera’s series The Harlem Globetrotters, and he played the character one last time for a September 1973 episode of The New Scooby-Doo Movies. Before the end of the year, he signed up for Ralph Bakshi’s movie Coonskin. In the hybrid live-action and animated film, he played the convict Pappy for live-action scenes and voiced characters Old Man Bone and Simple Savior. In the movie Pappy in live-action tells another convict some stories about his acquaintances in Harlem, and the animated sequences bring those stories to life.

In 1973 Scatman Crothers experienced a transition in his career as a vocal artist in animation, leaving behind an old character and voicing a new one. But both the old and new roles had one thing in common: Harlem, New York. Since 1970, Crothers had voiced the caricature of basketball player Meadowlark Lemon for Hanna-Barbera’s series The Harlem Globetrotters, and he played the character one last time for a September 1973 episode of The New Scooby-Doo Movies. Before the end of the year, he signed up for Ralph Bakshi’s movie Coonskin. In the hybrid live-action and animated film, he played the convict Pappy for live-action scenes and voiced characters Old Man Bone and Simple Savior. In the movie Pappy in live-action tells another convict some stories about his acquaintances in Harlem, and the animated sequences bring those stories to life.

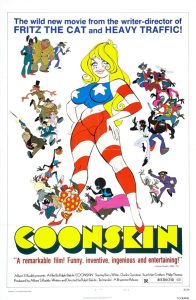

Ralph Bakshi directed Coonskin. At age 35 in 1973, he was already an animation veteran, having started at Terrytoons in the late 1950s. He produced and directed Paramount Cartoon Studio’s last films in 1967 and worked on the Spider-Man television series the following year. In 1973 he was at a peak in his career as a director with the successes of his pioneering X-rated animated feature films Fritz the Cat (1972) and Heavy Traffic (1973). Paramount Pictures reunited with him for Coonskin, agreeing to distribute the film — at first.

Like much of Bakshi’s work, Coonskin is never visually dull. Photographs of actual urban locations serve as backgrounds for the animated scenes, and the cartoon characters cavort over the photos. There are inventive allusions to earlier cartoons. The film’s transition from live-action to animation begins with a cartoon backdrop of concentric rings, not unlike those that opened Warner Brothers’ theatrical cartoons. The animation of the characters effectively blends smooth movements with stylized poses familiar to devotees of Bakshi’s work.

Coonskin treads on some familiar thematic turf in its plot. The film begins with southern convicts Pappy and Randy escaping from their cells and waiting in the prison yard for Randy’s two friends to arrive to drive them off the grounds. While they wait, Pappy spins his yarns about his friends Brother Bear, Brother Rabbit, and Preacher Fox and their exploits after leaving the South for better opportunities in Harlem. The film isn’t the first cartoon to depict African Americans as southern characters, but it is the first since Bugs Bunny’s 1953 episode Southern Fried Rabbit. Coonskin is novel in being a cartoon addressing the Great Migration of the early twentieth century, in which millions of African Americans left the South for the North and the West Coast from the 1910s to the early 1970s. However, the radio comedy Amos ‘n’ Andy was also about African American southerners making a living in the North, and Coonskin came forty years after Amadee Van Beuren’s brief animated adaptation of that series.

Coonskin treads on some familiar thematic turf in its plot. The film begins with southern convicts Pappy and Randy escaping from their cells and waiting in the prison yard for Randy’s two friends to arrive to drive them off the grounds. While they wait, Pappy spins his yarns about his friends Brother Bear, Brother Rabbit, and Preacher Fox and their exploits after leaving the South for better opportunities in Harlem. The film isn’t the first cartoon to depict African Americans as southern characters, but it is the first since Bugs Bunny’s 1953 episode Southern Fried Rabbit. Coonskin is novel in being a cartoon addressing the Great Migration of the early twentieth century, in which millions of African Americans left the South for the North and the West Coast from the 1910s to the early 1970s. However, the radio comedy Amos ‘n’ Andy was also about African American southerners making a living in the North, and Coonskin came forty years after Amadee Van Beuren’s brief animated adaptation of that series.

Coonskin’s characters and hybrid film style draw comparisons to Walt Disney’s 1946 hybrid feature Song of the South. To be sure, both movies use anthropomorphic animated animals to act out the tales told be Uncle Remus and Pappy. Both films have a vignette style, and they use central live-action characters as the anchors for the multiple animated stories. Even Pappy’s scat-singing of “Zha-bee-do-bee-do” in the opening sequence’s song seems to reference Uncle Remus’s song “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah.”

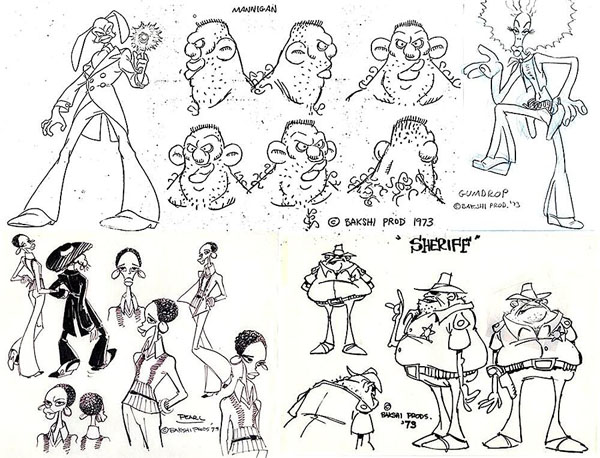

In a sense Coonskin is a product of its time. Blaxploitation films were money-makers for Hollywood distributors in the early 1970s. This genre consisted of African American protagonists fighting European American villains in movies of cheap budgets, violent scenes, sexual scenes, and urban settings—especially in Harlem. The films Cotton Comes to Harlem and Hell Up in Harlem preceded Coonskin. Much of the sexual content in Coonskin concerns a woman representing the United States of America. In one scene she cries “Rape!” in the presence of an African American figure, who is then immediately lynched. Another animated woman is a southern prostitute who happens to be the daughter of the sheriff, who looks like a Bakshi version of DePatie-Freleng’s cartoon sheriff Hoot Kloot from this same period.

Coonskin was also timely in its approach to social commentary. Its release barely predated the premiere of Saturday Night Live, which often resorted to broad ethnic caricature to parody the tropes informing the caricature in the show’s early seasons. It was a new, radical school of comedy. Previous cartoons addressed ethnic inequality by avoiding the gross blackface-inspired bug eyes and big lips for African American characters, as in the groundbreaking message-cartoon Brotherhood of Man from United Productions of America in 1947. Then in 1970 Hanna-Barbera found ways to use African American characters without the minstrel designs to entertain kids in The Harlem Globetrotters and Josie and the Pussycats. Rankin-Bass followed suit with The Jackson Five in 1971, as did Filmation with Fat Albert in 1972. Coonskin dared to resurrect the minstrel-style caricature but only to subvert it, as when one big-lipped character leaving the South for Harlem muses that in that city there would be “no more soft-shoeing, happy-acting, back-busting.” The movie also brought back the minstrel-type dialect for African Americans after other animation studios had avoided it ever since Paramount’s own Buzzy the Crow in the 1950s.

Coonskin was also timely in its approach to social commentary. Its release barely predated the premiere of Saturday Night Live, which often resorted to broad ethnic caricature to parody the tropes informing the caricature in the show’s early seasons. It was a new, radical school of comedy. Previous cartoons addressed ethnic inequality by avoiding the gross blackface-inspired bug eyes and big lips for African American characters, as in the groundbreaking message-cartoon Brotherhood of Man from United Productions of America in 1947. Then in 1970 Hanna-Barbera found ways to use African American characters without the minstrel designs to entertain kids in The Harlem Globetrotters and Josie and the Pussycats. Rankin-Bass followed suit with The Jackson Five in 1971, as did Filmation with Fat Albert in 1972. Coonskin dared to resurrect the minstrel-style caricature but only to subvert it, as when one big-lipped character leaving the South for Harlem muses that in that city there would be “no more soft-shoeing, happy-acting, back-busting.” The movie also brought back the minstrel-type dialect for African Americans after other animation studios had avoided it ever since Paramount’s own Buzzy the Crow in the 1950s.

Original newspaper ad (Click to enlarge)

Especially tragic is that the film seems to exist without a purpose, except to shock with ethnic caricature for its own sake. For example, Uncle Remus told his stories in Song of the South with the goal of his juvenile listeners learning moral lessons. Pappy, in contrast, tells his stories either to entertain Randy while they wait or to amuse himself, but neither character develops or evolves as a result of the stories. Rather, when the film transitions from animation back to live-action, Randy complains to a chuckling Pappy, “What you laughing at? We’re dead!” The complaint suggests that the animated stories wasted his time. Also, one vignette features a mammy-type figure shooting guns at a pancake rolling on its edge. The scene is a reference to the Aunt Jemima pancake brand, but what is the point of firing at a pancake? The drudgery of domestic service and the threat of sexual violence against African American maids by their employers would seem more powerful targets to address than a mere product of the labor itself.

Coonskin’s legacy today is as a cautionary tale. Back in the mid-1970s, a European American could announce an attempt to write and direct a tale that fetishizes African American life in Harlem as a violent and sexual cartoon fantasy, and no one would bat an eyelash. And if a viewer today accepts that Coonskin is a European American’s fantasy about Harlem and nothing more, then the viewer does not expect much—if any—accuracy about the Harlem they see on screen. One may be dismayed by the crudeness of the ethnic imagery without worrying that the filmmaker is presenting it as an earnest slice-of-life look at Harlem. But too much time may have passed in half a century for audiences to look beyond the caricatures and dialect and to overlook Bakshi’s European American ethnicity in his development of the film. He has every right to portray African American characters however he wants, but he was very audacious in proudly crediting himself as not only the writer-director of the film but also the lyricist for that opening number, which he titled “Ah’m a Nigger Man”—a title that both involves an ethnic slur and the minstrel dialect.

Coonskin’s legacy today is as a cautionary tale. Back in the mid-1970s, a European American could announce an attempt to write and direct a tale that fetishizes African American life in Harlem as a violent and sexual cartoon fantasy, and no one would bat an eyelash. And if a viewer today accepts that Coonskin is a European American’s fantasy about Harlem and nothing more, then the viewer does not expect much—if any—accuracy about the Harlem they see on screen. One may be dismayed by the crudeness of the ethnic imagery without worrying that the filmmaker is presenting it as an earnest slice-of-life look at Harlem. But too much time may have passed in half a century for audiences to look beyond the caricatures and dialect and to overlook Bakshi’s European American ethnicity in his development of the film. He has every right to portray African American characters however he wants, but he was very audacious in proudly crediting himself as not only the writer-director of the film but also the lyricist for that opening number, which he titled “Ah’m a Nigger Man”—a title that both involves an ethnic slur and the minstrel dialect.

Even in the 1970s, others treaded more lightly. Hanna-Barbera actually hired an African American consultant for The Harlem Globetrotters in order to avoid the very visual and verbal tropes that Bakshi deliberately used. As Ken Spears later told me, “We didn’t want the Amos ‘n’ Andy thing.” After production of Coonskin wrapped, Scatman Crothers returned to Hanna-Barbera—this time, to voice Hong Kong Phooey. The protagonist was an anthropomorphic dog, and Crothers’s voice is unmistakably familiar. But the dog lacks the big lips and bugged eyes of the figures he had just voiced for Coonskin.