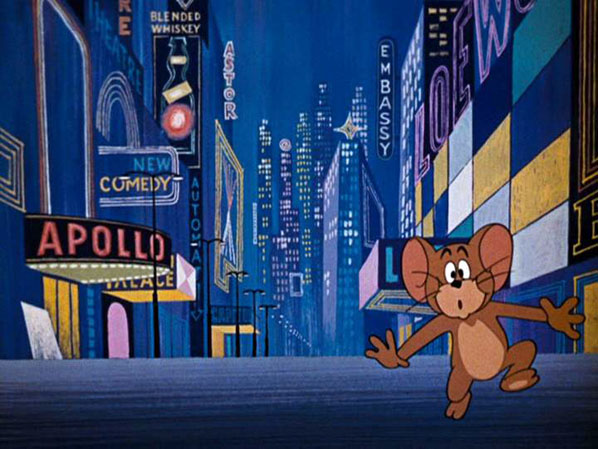

In Gene Deitch’s essay for Cartoon Research about his work on Tom and Jerry, he wrote, “I worked personally on every phase of the project.” That work included “designing the backgrounds.” Therefore, he was responsible for the first few seconds of his series finale Carmen Get It (1962). Those few seconds present a unique, abstract view of New York City, and the city’s image reflects Deitch’s perspective of the city and his interpretation of Tom and Jerry there.

The cartoon begins with Tom chasing Jerry through city streets. Jerry’s arrival at the Metropolitan Opera ultimately reveals the city as New York. However, the previous seconds present New York’s various theaters in one neighborhood despite their actual locations in separate parts of the city. The Astor and the Embassy were on Broadway, but the Apollo was—and still is—in Harlem. If Deitch oversaw the backgrounds, he would have had to instruct the background artist to place those theater names in the scene. Also, Tom and Jerry run through New York with an ease reflecting Deitch’s previous years in New York before moving to the Czech Republic. They do not come across as country bumpkins, as Jerry is in Mouse in Manhattan (1945).

The cartoon begins with Tom chasing Jerry through city streets. Jerry’s arrival at the Metropolitan Opera ultimately reveals the city as New York. However, the previous seconds present New York’s various theaters in one neighborhood despite their actual locations in separate parts of the city. The Astor and the Embassy were on Broadway, but the Apollo was—and still is—in Harlem. If Deitch oversaw the backgrounds, he would have had to instruct the background artist to place those theater names in the scene. Also, Tom and Jerry run through New York with an ease reflecting Deitch’s previous years in New York before moving to the Czech Republic. They do not come across as country bumpkins, as Jerry is in Mouse in Manhattan (1945).

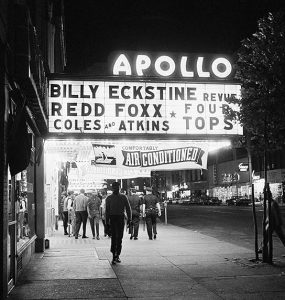

Especially poignant is that, of all the theaters in the background, the Apollo is at the forefront of the background. Deitch’s familiarity with the Apollo as part of New York is part of a tradition of New York animators’ references to local African American entertainment—a tradition dating back to Max Fleischer’s animators visiting the Cotton Club in the 1930s. Back then, Betty Boop cavorted with characters played by Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong, and the characters’ settings of caves and jungles symbolized Harlem. In contrast, the placement of Tom and Jerry by the Apollo suggests that they are in Harlem itself. The chase from the point of view of the animals shows only the legs of human passers-by. Therefore, the film leaves open the possibility of some of those passers-by being African Americans walking through Harlem. Moreover, unlike those Fleischer films, Carmen Get It does not depict Harlem as a scary and dangerous place for anyone not African American. Rather, it is just another section of New York City.

In a sense Carmen Get It contains Tom and Jerry’s last nod to African American culture. When William Hanna and Joseph Barbera directed the series, they restricted the references largely to music. Scott Bradley occasionally incorporated African American compositions into his scores for episodes, and Louis Jordan’s “Is You Is Or Is You Ain’t My Baby” is the musical centerpiece of Solid Serenade (1946). However, these references and Tom’s donning of a zoot suit in The Zoot Cat (1944) are in settings far removed from African Americans themselves. The street scene in Carmen Get It finally places Tom and Jerry in the neighborhood that shaped so many of the references.

In a sense Carmen Get It contains Tom and Jerry’s last nod to African American culture. When William Hanna and Joseph Barbera directed the series, they restricted the references largely to music. Scott Bradley occasionally incorporated African American compositions into his scores for episodes, and Louis Jordan’s “Is You Is Or Is You Ain’t My Baby” is the musical centerpiece of Solid Serenade (1946). However, these references and Tom’s donning of a zoot suit in The Zoot Cat (1944) are in settings far removed from African Americans themselves. The street scene in Carmen Get It finally places Tom and Jerry in the neighborhood that shaped so many of the references.

Deitch’s essay mentions his removal by MGM from Tom and Jerry because of the departure of the distributor’s president Joe Vogel in early 1963. As a result, Deitch could not further integrate his perspective of New York into the characters. His successor Chuck Jones kept them out of New York, and no further cultural references to African Americans appear in the series. Meanwhile, the Civil Rights Act did not end legal segregation until 1964, and MGM distributed Deitch’s films to segregated venues. Therefore, the appearance of Tom and Jerry by the Apollo in Carmen Get It was somewhat progressive, because it showed an African American neighborhood as a fundamental part of an American city and without “white only” and “colored only” signs separating the population. It was a subversive ode to tolerance from a series not always known for its subtlety or its ethnic progressivism.