Alice is a curious character in the Disney pantheon. She’s not a princess but has the popularity of one. She doesn’t have any magical powers, a plethora animal friends, or a lovely singing voice. She was famous long before Walt Disney transformed her into an animated character. In western children’s fantasy literature, she is part of the iconic triad that includes Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz and Wendy of Peter Pan. She’s a legacy portal fantasy and isekai (to borrow a Japanese anime/manga term) heroine that’s inspired hundreds of stories and spinoffs, especially when Alice’s books entered the public domain.

Alice is a curious character in the Disney pantheon. She’s not a princess but has the popularity of one. She doesn’t have any magical powers, a plethora animal friends, or a lovely singing voice. She was famous long before Walt Disney transformed her into an animated character. In western children’s fantasy literature, she is part of the iconic triad that includes Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz and Wendy of Peter Pan. She’s a legacy portal fantasy and isekai (to borrow a Japanese anime/manga term) heroine that’s inspired hundreds of stories and spinoffs, especially when Alice’s books entered the public domain.

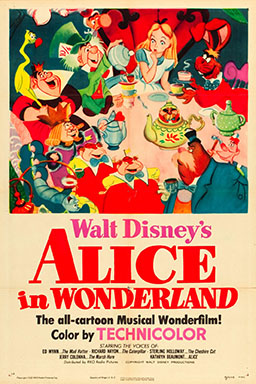

Without the influence of Walt Disney’s 1951 feature film, I speculate Alice would have remained a fixture in the entertainment zeitgeist. She would just have much less merchandise to her name and would be more revered akin to Beatrix Potter’s characters and C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia series. What makes Alice a fascinatingly curious Disney character is her movie strongly parallels the source material by Lewis Caroll (the nom de plume of mathematician and author Charles Dodgson) with much creative license. This is particularly true with Alice’s trademark mien. The Walt Disney Studio artists didn’t create Alice’s blonde hair tied back with bow and her frock with a white pinafore, but they did refine it for the silver screen.

Other depictions of Disney characters are now regarded as the standard. Snow White is always imagined with her Technicolor blue and yellow gown, while Sleeping Beauty always wears her golden tiara paired with a pink or blue dress. The Little Mermaid is now forever a bright redhead with a green tail and Cinderella is never seen without her classic chignon and sparkly white-blue ballgown. Meanwhile Alice has remained close to her illustrative origins.

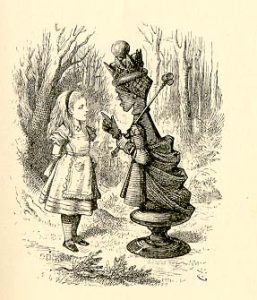

Alice by John Tenniel

Tenniel worked in the theater and often transposed dramatic scenes to paper. His work was noted to be very theatrical compared to other cartoonists. Thanks to his photographic memory, he was also a master of portraiture and caricature. Tenniel knew how to draw from real life thanks to his classical education at the Royal Academy of Arts based in London, but he included details he only saw in his imagination. I describe Tenniel’s work in that he had the ethos of high, fine art but has the muckrake details of the common sketch artist His influences are still seen today, but none more so than the original Alice in Wonderland.

He became Punch’s Principal Cartoonist circa 1864. Around that time Lewis Caroll was fiddling around with the draft for Alice in Wonderland and he drew his own conceptions of what Alice looked like. Apparently his renderings weren’t the best, so he sought the services of a professional artist. His eyes fell on Tenniel, because Carroll loved his caricatures.

When it came to their respective artistic mediums, Caroll and Tenniel were masters. Caroll knew how to spin a word and poetic verse with the same elegance as a mathematical formula, while Tenniel inked small details into his cartoons while maintaining a simplicity that didn’t overwhelm a viewer’s eyes. It was a match made in Wonderland!

There are scant remnants of the correspondence between Tenniel and Caroll during their collaboration on Alice. The remaining letters and diaries allude to an intense dialogue over the development of Caroll’s iconic characters. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has one of the few surviving illustrations showing the development of Alice. The image depicts a concept profile of Alice’s visage by Tenniel with notes from Caroll that read: “A little bit off eyebrow. Eyebrow & eyelid lighter. Eyelash – a little too long. Clear away a line on nose next to cheek. A little bit more light on end of nose.”

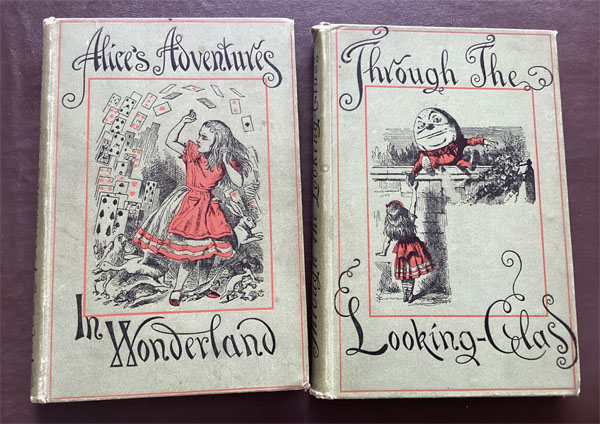

Despite being a literary master, Caroll didn’t bog down Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass with descriptions of his characters and their world. The books read more like an observation with curious pondering about the imaginary lands. Caroll was interested in world building, but not to the extent seen as J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, J.K. Rowling, and Ursula Le Guin.

Despite being a literary master, Caroll didn’t bog down Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass with descriptions of his characters and their world. The books read more like an observation with curious pondering about the imaginary lands. Caroll was interested in world building, but not to the extent seen as J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, J.K. Rowling, and Ursula Le Guin.

He relied more on Alice’s situations and Tenniel’s illustrations to augment his world building. Tenniel was an experienced artist by the time he was hired to illustrate the Alice books. The Victoria and Albert Museum wrote: “…Tenniel invented his own characterisations, drawing from a vast range of sources, including fine art, natural history, heraldry, caricature and his previous work for Punch.” Caroll, however, was involved with the creation of the illustrations. He provided Tenniel with feedback about what to draw and where illustrations would be placed in the final print. When it comes to creating the characters iconic looks, however, writer and graphic novelist of Alice in Sunderland credits it all to Tenniel: “Carroll never describes the Mad Hatter: our image of him is pure Tenniel.”

It doesn’t appear Caroll micromanaged Tenniel, however, and he trusted the artist’s skills. The working relationship between the two legends is reminiscent of how modern comic book artists and writers work together. Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass are children’s books, but modern children’s illustration doesn’t work like the aforementioned described relationship. Unless an author doubles as the illustrator, they have little say in what is drawn for the book. Comic books, however, are written with dialogue and panel descriptions for the artist to manifest.

It doesn’t appear Caroll micromanaged Tenniel, however, and he trusted the artist’s skills. The working relationship between the two legends is reminiscent of how modern comic book artists and writers work together. Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass are children’s books, but modern children’s illustration doesn’t work like the aforementioned described relationship. Unless an author doubles as the illustrator, they have little say in what is drawn for the book. Comic books, however, are written with dialogue and panel descriptions for the artist to manifest.

Arguably Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass could be viewed as some of the first modern graphic novels because of the collaboration between author and artist.

Having written my own novels and studied Carroll’s personality, I hypothesize he was more concerned with how his words were being edited than being an overbearing presence for Tenniel. The illustrator was a professional, experienced artist who had a famous career long before he illustrated the Alice books. Caroll was aware of this so he left his collaborator to his own devices. (This is only speculation on my part based on my creative experience and knowledge of Caroll’s life.)

Alice’s portrayal is recognizable and simplistic: a frock with a pinafore and blonde hair tie back with a ribbon headband. Alice’s dress is traditionally blue but its color has changed to suit whatever publication she is in. When Walt Disney selected to bring the heroine to an animated feature, he and his team had an abundance of Tenniel’s work for inspiration not to mention numerous republishing of the book with reimagined depictions of the famous characters.

Alice’s portrayal is recognizable and simplistic: a frock with a pinafore and blonde hair tie back with a ribbon headband. Alice’s dress is traditionally blue but its color has changed to suit whatever publication she is in. When Walt Disney selected to bring the heroine to an animated feature, he and his team had an abundance of Tenniel’s work for inspiration not to mention numerous republishing of the book with reimagined depictions of the famous characters.

Mary Blair was tapped for creative and conceptual designs on Alice in Wonderland. Compared to Tenniel’s straightforward, detailed ink style, Blair is a modernistic almost minimalist artist who favors organic shape and bold color. They two couldn’t be more different, but Blair’s respect for Tenniel’s source material is more evident in her renderings of Alice. She kept the same iconic look, albeit minimalist. Blair’s blue, yellow, and white beribboned blur couldn’t be anyone by Alice. Blair’s Alice in Wonderland concepts are truer homages to Tenniel’s work than Salvador Dali’s surrealistic, brut version.

Blair and the Disney animation studio knew they were working with an truly recognizable heroine and if they changed too much, they’d face the slander of the 1950s versions of Internet trolls and hardcore Alice in Wonderland fanboys and girls.

Blair and the Disney animation studio knew they were working with an truly recognizable heroine and if they changed too much, they’d face the slander of the 1950s versions of Internet trolls and hardcore Alice in Wonderland fanboys and girls.

Walt Disney was possessive about his work and he wanted to own Alice through and through. While the work was in the public domain, Disney wanted his Alice to be the only Alice. It’s similar to how the Walt Disney Company wants their films to be the only fairytale films and why those cheap knock-offs films follow as to the copyright borderline without getting sued. Speaking of lawsuits, there was another Alice in Wonderland film that premiered in 1949. It was directed by American puppeteer and stop-motion animator Lou Bunin. Walt sued to keep Bunin’s film from a wide US release. He didn’t win his case because the works are in the public domain, but Walt used his influence to hinder Bunin’s work.

Bunin’s Alice is reminiscent of Tenniel’s original concept, just like Disney’s. The Disney fairytales’ source materials are hundreds of years old compared to Caroll’s works that are only a little over a century (I realize Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid is a young fairytale but it’s in the same sea as older fairytales). There are countless depictions of Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Rapunzel, and the Little Mermaid because the source materials were based on oral traditions and didn’t have original illustrations. It allowed the Walt Disney Studios endless creative liberties to depict these famous characters, while Alice was already visually represented in the zeitgeist like Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz.

If Disney had changed Tenniel’s Alice too much, it would have ruffled more feathers than a croquet flamingo or a dodo. While Alice is beloved Disney character, we also revere her illustrious literary origins.