In the wake of the popular and successful “Disneyland” anthology shows discussed last week, there was the inevitable flow of “copycats” who attempted to expand animation made for television into self-hosted half hour packages. This would gradually free even the major networks from providing live kid-show hosts to entertain and emcee between episodes of series too short in running length to fill out a half-hour by themselves, such as the original runs of “Gumby” and “Ruff ‘n’ Reddy.” The cartoon stars would generally, in the same manner as the Disney characters, express full awareness of their animated existence upon the new medium of television – and play it to full advantage. In at least one instance, an approach more akin to Disney’s would be tried by a rival network to provide live-action hosting for a package of old theatrical cartoons, with the characters exchanging banter and interplay with the host through a TV screen on the set.

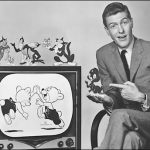

When CBS acquired the Terrytoons’ library of titles, they tried several formats to present the cartoons, far too numerous to remain within the confines of a single show. The “Barker Bill” show, a syndicated affair, expressed no real effort whatsoever, lifting a one-shot character from the short “Happy Circus Days” for a brief piece of introductory animation, then merely stringing cartoons together to fill out the running time, with reshot titles featuring the Barker’s face. “Mighty Mouse Playhouse”, “The Heckle and Jeckle Show”, and ‘Farmer Al Falfa and his Terrytoons Pals” all relied merely upon a short series of bumpers in which the hosting characters would speak directly to the children of the audience. Mighty: “Hold on to your seats, as we blast off to visit all of your favorite cartoon stars”. Heckle and Jeckle: “Tally ho and away we go” “Into another fun-filled cartoon show.” And so on. However, some additional effort went into planning the prime-time “CBS Cartoon Theater”, an effort (before the premiere of the “Heckle and Jeckle Show”) to showcase the works of what CBS considered to be Terry’s principal supporting players – Heckle and Jeckle, Gandy Goose and Sourpuss, Dinky Duck, and Little Roquefort. Hosting duties were supplied by an up-and-coming comedian who would soon rise to stardom and well-known prominence – Dick Van Dyke, who would provide spoken introductions to the shorts from a sort of “studio central” office with a large TV set in its center. The principal characters would appear in new animations on the TV screen, frequently razzing or playing tricks upon Van Dyke and generally up to mischief. Animation seems to have been supplied by usual suspects from the original studio, with the hand of Jim Tyer evidently visible, and in all likelihood some input by Connie Rasinski. Original voices also continue to be provided by Tommy Morrison and Roy Hallee. Surviving installments of the show have been in short supply online, but a sample broadcast from the show’s 1956 premiere is included here (in original black and white, as CBS had not yet gone to color). Notably, the instrumental music serving as the show’s theme is the same little jingle which appeared as a theme for Dinky Duck’s last theatrical release, It’s a Living.

When CBS acquired the Terrytoons’ library of titles, they tried several formats to present the cartoons, far too numerous to remain within the confines of a single show. The “Barker Bill” show, a syndicated affair, expressed no real effort whatsoever, lifting a one-shot character from the short “Happy Circus Days” for a brief piece of introductory animation, then merely stringing cartoons together to fill out the running time, with reshot titles featuring the Barker’s face. “Mighty Mouse Playhouse”, “The Heckle and Jeckle Show”, and ‘Farmer Al Falfa and his Terrytoons Pals” all relied merely upon a short series of bumpers in which the hosting characters would speak directly to the children of the audience. Mighty: “Hold on to your seats, as we blast off to visit all of your favorite cartoon stars”. Heckle and Jeckle: “Tally ho and away we go” “Into another fun-filled cartoon show.” And so on. However, some additional effort went into planning the prime-time “CBS Cartoon Theater”, an effort (before the premiere of the “Heckle and Jeckle Show”) to showcase the works of what CBS considered to be Terry’s principal supporting players – Heckle and Jeckle, Gandy Goose and Sourpuss, Dinky Duck, and Little Roquefort. Hosting duties were supplied by an up-and-coming comedian who would soon rise to stardom and well-known prominence – Dick Van Dyke, who would provide spoken introductions to the shorts from a sort of “studio central” office with a large TV set in its center. The principal characters would appear in new animations on the TV screen, frequently razzing or playing tricks upon Van Dyke and generally up to mischief. Animation seems to have been supplied by usual suspects from the original studio, with the hand of Jim Tyer evidently visible, and in all likelihood some input by Connie Rasinski. Original voices also continue to be provided by Tommy Morrison and Roy Hallee. Surviving installments of the show have been in short supply online, but a sample broadcast from the show’s 1956 premiere is included here (in original black and white, as CBS had not yet gone to color). Notably, the instrumental music serving as the show’s theme is the same little jingle which appeared as a theme for Dinky Duck’s last theatrical release, It’s a Living.

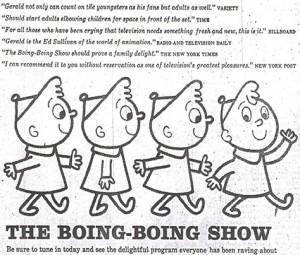

CBS’s next prime-time move was to employ the services of UPA studios for a new half-hour package of miscellaneous shorts. While none of the episodes produced featured any previously-recognized UPA theatrical character, someone got the idea to use one of the studio’s secondary stars in an odd hosting role as a “hook” to sell the program by name – resulting in the title, “The Boing Boing Show” (1956). Negatives for this show’s contents have been preserved in color, though, sadly, no intact broadcasts appear to have been made available. Instead, some cobblings of elements from the show were released to the VHS market, with most of the original opening title animation and a few interstitial bumpers of the “star” included. One such release is embedded below. Gerald’s appearance amounts to walk-ons and the utterance of a few sound effects or music notes to put us in the mood for the next cartoon, while some unnamed stage-hands set up basic imagery around him. While the effects track seems original, the theme music presented on the VHS releases appears fake, too modern and overdubbed in sound, undoubtedly to avoid paying royalties to whoever was the original composer.

CBS’s next prime-time move was to employ the services of UPA studios for a new half-hour package of miscellaneous shorts. While none of the episodes produced featured any previously-recognized UPA theatrical character, someone got the idea to use one of the studio’s secondary stars in an odd hosting role as a “hook” to sell the program by name – resulting in the title, “The Boing Boing Show” (1956). Negatives for this show’s contents have been preserved in color, though, sadly, no intact broadcasts appear to have been made available. Instead, some cobblings of elements from the show were released to the VHS market, with most of the original opening title animation and a few interstitial bumpers of the “star” included. One such release is embedded below. Gerald’s appearance amounts to walk-ons and the utterance of a few sound effects or music notes to put us in the mood for the next cartoon, while some unnamed stage-hands set up basic imagery around him. While the effects track seems original, the theme music presented on the VHS releases appears fake, too modern and overdubbed in sound, undoubtedly to avoid paying royalties to whoever was the original composer.

When Hanna-Barbera broke full-force into producing half-hour packages for TV, their first three ventures with sponsorship by Kellogg’s all spotlighted their starring characters as show hosts. Though the individual episodes included in the programs would rarely have the characters acknowledging a cartoon or television existence (perhaps because the films were also being set up with individual main titles for distribution in foreign markets and possibly in foreign theatrical venues where the references to television wouldn’t have made sense), each show would not only feature fresh animation of the star promoting the cereal, but a series of interstitial bumpers in which the various characters featured on the show would cross-over between their own respective animated worlds to interact directly with one another, and always with a wrap-up line leading to an intro to the next cartoon or next week’s show. Curiously, H-B chose not to use this style in its prime-time ventures such as “The Flintstones”, where the characters would generally only speak to the audience if presenting an animated commercial pitch of this week’s product. The “hosted” output thus included “The Huckleberry Hound Show” (1958), “The Quick Draw McGraw Show” (1959). and “The Yogi Bear Show” (1961). A great assortment of bumper playlists presenting the characters acknowledging their presence on the shows is available below. There is so much terrific footage that went into these and various other bumpers of the shows, that someone should really compile a video package of the bumpers alone, to preserve the entirety of these great shows’ legacies.

When Hanna-Barbera broke full-force into producing half-hour packages for TV, their first three ventures with sponsorship by Kellogg’s all spotlighted their starring characters as show hosts. Though the individual episodes included in the programs would rarely have the characters acknowledging a cartoon or television existence (perhaps because the films were also being set up with individual main titles for distribution in foreign markets and possibly in foreign theatrical venues where the references to television wouldn’t have made sense), each show would not only feature fresh animation of the star promoting the cereal, but a series of interstitial bumpers in which the various characters featured on the show would cross-over between their own respective animated worlds to interact directly with one another, and always with a wrap-up line leading to an intro to the next cartoon or next week’s show. Curiously, H-B chose not to use this style in its prime-time ventures such as “The Flintstones”, where the characters would generally only speak to the audience if presenting an animated commercial pitch of this week’s product. The “hosted” output thus included “The Huckleberry Hound Show” (1958), “The Quick Draw McGraw Show” (1959). and “The Yogi Bear Show” (1961). A great assortment of bumper playlists presenting the characters acknowledging their presence on the shows is available below. There is so much terrific footage that went into these and various other bumpers of the shows, that someone should really compile a video package of the bumpers alone, to preserve the entirety of these great shows’ legacies.

One rare instance where cartoon-consciousness enters into an actual episode of The Huckleberry Hound Show appears in the first episode of Pixie and Dixie and Mr. Jinks, entitled Cousin Tex (10/2/58). The film’s basic idea is a sort-of reworking/update on Tom and Jerry’s Jerry’s Cousin, with the two mice receiving unexpected protection by means of a long tall “Texas-sized” mouse, proficient in the arts of roping, branding, and generally making sure that no cantankerous cat gets a mite out of hand. But the interesting factoid for the present article’s purposes appears at the very beginning of the film, where Pixie and Dixie appear seated on the living room sofa, enjouing a cartoon on TV – not in this case of themselves. Now what would the concept of a cartoon be to a pair of mice who are already cartoons themselves, rendered in highly-limited animation? What else? Childish stick figures, rendered in stark black and white, much like the old scrawlings that were “Porky’s Preview”. The film onscreen, of a character known as “Knockout Mouse”, even ends with rudimentary titles in outline drawing closely resembling the “syndication” end titles created by H-B for the very Pixie and Dixie cartoon we are watching! Dixie wishes they had a friend like Knockout to beat up on cats, but Pixie reminds him that Knockout isn’t really for real. “But I’m for real, shorty” declares Jinks, popping up over the back of the sofa cushion. The terrified mice beat a retreat to the mousehole, where Jinks warns them, ”That mices beatin’ up the cat stuff only happens in cartoons – so don’t get any fancy ideas.” Within the mousehole, Dixie continues to wish, “Well, we can dream, can’t we?”

• Cousin Tex is on Facebook – CLICK HERE.

H-B’s last consciously-hosted half-hours would be The Magilla Gorilla Show and The Peter Potamus Show (both 1964). Here, hosting duties were kept to a minimum, appearing only as one-time series leaders and a closing bumper (often referred to as a “curtain call”), repeated over and over in each week’s show, rather than presenting new encounters between the characters each week. The cast of the Magilla show was featured in a singing walk-on in the show’s opening titles, interacted together in the curtain call, and Magilla portrayed a TV cameraman in the weekly closing. Peter didn’t interact with his co-stars except in the one-minute “curtain call” before the closing credits. Each of these finale bumpers further reminded viewers to watch the other of the two shows at its respective air time. Much of this footage exists in multiple truncated and altered versions. Part of this was due to the decision to interchange elements of the respective shows in mid-run. Ricochet Rabbit thus moved from Magilla to the Peter Potamus roster, with Breezly Bruin and Sneezly Seal making the move from Potamus to Gorilla. Thus, alternate opening credits had to be shot for Magilla, and both “curtain calls” needed alternate filmings to interchange characters. After original syndication, all references to Ideal Toys had to be removed from both sets of opening and closing credits, leading to drastic shortening of the sequences. It is only through the dedication of collectors over at least a decade or more that these sequences have been restored, seemingly as far as humanly possible from disparate elements, as presented below. There is still at least one artifact, in that original sound for the Magilla first-season curtain call seems not to have been located, and is replaced with track from the reshoot. This accounts for Magilla’s voice repeating “So Long” at two places where the line is mouthed on screen by Punkin’ Puss and Mushmouse, whose tracks still appear to be missing. Also, the first season curtain call for Peter Potamus remains only available in black and white. Hopefully, the search goes on.

Another well-known self-hosted half-hour of late 50’s=60’s animation was Jay Ward’s “Rocky the Flying Squirrel”, also known as Rocky and his Friends (1959) and soon after as “The Bullwinkle Show”, among other retitles. Leaders and bumpers for these shows have again gone through a myriad of retoolings, cutting out references to sponsors, changing musical underscores to an alternate theme written for a later season, and ultimately pasting over series banners with “The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends” for DVD issue. Rest easy that uncut full color 35mm elements exist for the original first-season titles at UCLA, with original score (which recently saw a big-screen public presentation hosted by Jay’s daughter at the Hammer Theater, allowing for high-resolution viewing of the entirety of episode 2 of the series, in brilliant color). It’s a shame if you happened to miss it. For those who did, a pretty-decent reconstruction of episode 1 is included below. It remains inaccurate in including bumpers for the two Rocky cartoons visually retaining the DVD retitling, but at least fits them with the proper musical score. Animated commercials featuring the characters are also included.

Ward’s creations always maintained a certain irreverence in their presentation and asides to the audience, and were never above poking fun at television or film to get a laugh. Though the characters didn’t always acknowledge themselves as being cartoons, I recall a particularly telling sequence in a Rocky episode, which I cannot peg the identity of from memory among the seemingly hundreds of individual episodes produced, in which Boris Badenov nearly loses his mojo. In furtherance of the latest nefarious plan, he is about to don his umpteenth disguise of the season, and break into his usual “Allow me to introduce myself…”, but begins to utter the line weakly and half-heartedly, Natasha asks him what is wrong. Boris expresses to her that this has gone on and on over again for what seems forever, and that it is totally ridiculous to expect such a lame disguise to succeed. Sooner or later, it is inevitable that the squirrel will see right through his latest ploy, and everything will be lost. So what’s the use? Natasha reminds him to look at a particular numbered rule within the No-Goodnik’s handbook, which reads, simply, “There is no one more gullible than a cartoon hero.” Still without genuine conviction or any attempt to put his lines over with feeling, Boris makes his introduction to Rocky. All that the squirel can respond with is his usual state of total unknowing confusion. “That voice. Where have I heard that voice before?” A wide smile spreads across Boris’s face, and he exchanges a glance of confidence with Natasha. Boris is back in the game.

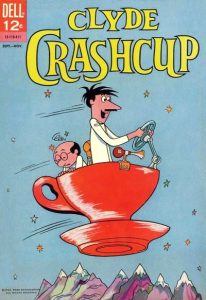

Publicity still from “Clyde Crashcup Invents Baseball”

Crashcup is ably assisted by a little fellow in lab coat and glasses named Leonardo (any descendancy from Da Vinci presumably intended). Leonardo is never heard to understandably speak, but communicates all his suggestions to Clyde through whispers in his ear, with Clyde’s verbal reactions to them providing all the information we need as to what the suggestion was. For example, when Crashcup attempts to invent the chair, designing a seat in a geometric shape that in no manner resembles a human posterior, a whisper from Leonardo prompts Clyde to remark, “What do you mean, it’s not shaped that way?” Poor Leonardo is usually the fall guy for several of Clyde’s failures, and often forced to take the blame and reprimands from Clyde when the inventive genius’s pride refuses to acknowledge the shortcomings of his own ideas. Yet, Leonardo often serves as the voice of reason, even if in a whisper, sometimes steering Clyde back upon a path where success seems nearly within their grasp – but always ultimately elusive. It is further notable that Leonardo never once informed Clyde that something he was working on had already been invented – proving that Leonardo was no more current than Clyde upon pop culture. Oh well, being under the thumb of Clyde all day, I guess he doesn’t get out much.

Crashcup is ably assisted by a little fellow in lab coat and glasses named Leonardo (any descendancy from Da Vinci presumably intended). Leonardo is never heard to understandably speak, but communicates all his suggestions to Clyde through whispers in his ear, with Clyde’s verbal reactions to them providing all the information we need as to what the suggestion was. For example, when Crashcup attempts to invent the chair, designing a seat in a geometric shape that in no manner resembles a human posterior, a whisper from Leonardo prompts Clyde to remark, “What do you mean, it’s not shaped that way?” Poor Leonardo is usually the fall guy for several of Clyde’s failures, and often forced to take the blame and reprimands from Clyde when the inventive genius’s pride refuses to acknowledge the shortcomings of his own ideas. Yet, Leonardo often serves as the voice of reason, even if in a whisper, sometimes steering Clyde back upon a path where success seems nearly within their grasp – but always ultimately elusive. It is further notable that Leonardo never once informed Clyde that something he was working on had already been invented – proving that Leonardo was no more current than Clyde upon pop culture. Oh well, being under the thumb of Clyde all day, I guess he doesn’t get out much.

A typical example from the series, Crashcup Invents Flight (12/6/61), is featured below. Crashcup’s pencil gets busy drawing arm wings, the “whirling wing”, being a sort of beany-copter cap, and the internal combustion airplane engine. Clyde even gets in a little hand-labor by constructing his “heavier-than-air” craft – a dirigible composed of solid bricks! The episode may be unique among the series in having Clyde actually faced with the reality that technology has beaten him to the punch – as Clyde crashes head-on into the intake of an oncoming jet fighter. Yet, Clyde seems to remain oblivious to the fact that this strange object was an invention of man – and goes right on with his inventing. Leonardo sums up the whole affair with a whisper at the closing, which even Clyde has to acknowledge is logical and correct: “Flying is for the birds!” Perhaps all Clyde needs is to go back to the university for some refresher courses, under the tutelage of Professor Grampy.

• “Crashcup Invents Flight” is at ARCHIVE.ORG

NEXT WEEK: More studios from the dawn of 1960’s TV.