The advent of animation for television brought about some mixed trends in our survey of cartoons self-conscious of their medium. Certainly, the concept of being projected in front of a massed seated audience would more-or-less disappear when short cartoons ceased to be a regular part of the theater-going experience. But there was still opportunity for interaction with the viewers, on a more personal level, in small batches before their sets in the living rooms of the average home. As packaging of programming grew from mere individual shorts into weekly or even daily half-hour blocks, the concept further grew of having characters from the show literally become the host, in place of local or syndicated live-action emcees, clowns, sheriffs, engineers, spacemen, etc., who were originally cast to provide entertainment between presentation of new and old theatrical cartoons, ultimately saving local markets and networks significant expense in production. On the higher end of the production scale, it was further found that audiences could to a degree be fooled into taking new interest in old shorts from decades before if framed within new “bridging animation” featuring classic characters, often in a hosting or backstage studio role, integrating the stock footage to make an entire half-hour or hour presentation look as seamless as possible, telling some continuous story as if entirely newly-minted. And, on rare occasions, gags would come into play that still followed the old leads of their theatrical ancestors, presenting an idea or two that might have worked just as well in a theatrical film.

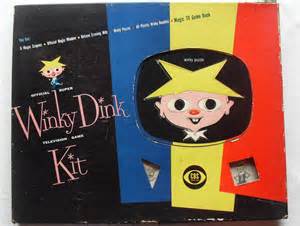

One of the earliest concepts for character/viewer interaction via the cathode-ray tube was possibly one of the strangest – and an idea that likely got a good many kids in trouble and a good many parents irate. It was called Winky Dink and You (CBS, 1953-57), hosted by Jack Barry, with offscreen voice-overs by Mae (Betty Boop) Questel. The original show barely qualifies as animation at all, being more frequently constructed of still drawings, sometimes depicted against panning backgrounds, showing the title character in some situation, while narration of his troubles was provided by the host or verbal comments were mouthed by Questel without lip movement onscreen. The gimmick, however, was the way in which the kiddies were supposed to help out the hero to accomplish his tasks or adventures. A special piece of equipment was sipposed to be purchased by the parents at the local toy store or other participating retail outlet, called a “magic screen”. As I understand it, it was some form of semi-soft flexible clear plastic, large enough to cover the average family-size TV screen, and held into place by the static electricity produced by old TV screens in operation, by rubbing the screen firmly against the tube glass before use with some form of cloth included in the purchased kit. (One wonders how well this method works, and how many magic screens probably fell off the set in the middle of broadcasts.)

One of the earliest concepts for character/viewer interaction via the cathode-ray tube was possibly one of the strangest – and an idea that likely got a good many kids in trouble and a good many parents irate. It was called Winky Dink and You (CBS, 1953-57), hosted by Jack Barry, with offscreen voice-overs by Mae (Betty Boop) Questel. The original show barely qualifies as animation at all, being more frequently constructed of still drawings, sometimes depicted against panning backgrounds, showing the title character in some situation, while narration of his troubles was provided by the host or verbal comments were mouthed by Questel without lip movement onscreen. The gimmick, however, was the way in which the kiddies were supposed to help out the hero to accomplish his tasks or adventures. A special piece of equipment was sipposed to be purchased by the parents at the local toy store or other participating retail outlet, called a “magic screen”. As I understand it, it was some form of semi-soft flexible clear plastic, large enough to cover the average family-size TV screen, and held into place by the static electricity produced by old TV screens in operation, by rubbing the screen firmly against the tube glass before use with some form of cloth included in the purchased kit. (One wonders how well this method works, and how many magic screens probably fell off the set in the middle of broadcasts.)

Also included in the kit were a set of crayons, of a substance designed to be capable of easily rubbing off the screen with the cloth after application. During the show, various outlines or patterns would be briefly shown in isolation of any prop or background, and the kids would be asked to take out a particular crayon and trace the lines depicted. Once time deemed sufficient by the producers for the kids to complete the tracing elapsed, the scene on the TV would suddenly change to a full background or set, with the video outline no longer present. The lines the children had drawn would thus become conjoined with other objects now appearing on the screen, letting the drawn lines complete a larger image which might be a vehicle, an animal, or some prop needed by the hero in his quest. The concept was indeed clever, and was believed by the producers to be conducive to promoting child interest in artwork. Yet, rumors continue to be told of children who became interested in this artwork a little too much – as in those whose parents had not in fact purchased a magic screen kit, or who didn’t themselves know how to properly affix the magic screen, or who had simply run out of crayons of the washable varuety. The result was that the kids would improvise to participate in the show, drawing on the actual TV tube with anything they could get their hands on, often not designed to be washable.

Also included in the kit were a set of crayons, of a substance designed to be capable of easily rubbing off the screen with the cloth after application. During the show, various outlines or patterns would be briefly shown in isolation of any prop or background, and the kids would be asked to take out a particular crayon and trace the lines depicted. Once time deemed sufficient by the producers for the kids to complete the tracing elapsed, the scene on the TV would suddenly change to a full background or set, with the video outline no longer present. The lines the children had drawn would thus become conjoined with other objects now appearing on the screen, letting the drawn lines complete a larger image which might be a vehicle, an animal, or some prop needed by the hero in his quest. The concept was indeed clever, and was believed by the producers to be conducive to promoting child interest in artwork. Yet, rumors continue to be told of children who became interested in this artwork a little too much – as in those whose parents had not in fact purchased a magic screen kit, or who didn’t themselves know how to properly affix the magic screen, or who had simply run out of crayons of the washable varuety. The result was that the kids would improvise to participate in the show, drawing on the actual TV tube with anything they could get their hands on, often not designed to be washable.

Parents’ complaints are believed to some degree to have been behind the ultimate demise of the show. And yet, in 1969, history would repeat itself, as the idea was hatched to revive the series in color, as syndicated stand-alone five-minute cartoons with reasonable animation but low budgets, produced by Fred Calvert. Lionel Wilson would be hired to dig out of moth balls his old voices from the “Tom Terrific” series for Terrytoons, which became interchangeably used in the new series (Tom’s voice for Winky, and Mighty Manfred’s voice for Winky’s dog Woofer). Even a villain or two in the new series didn’t sound far from the voice of Crabby Appleton. While an array of ideas were devised for using the shape-tracing gimmick, leading to a good many sales of new magic screen kits in local Toys “R” Us outlets, the color series generally lacked the inventiveness and spirit of its Tom Terrific ancestor, though certainly a step up from Winky’s 1953 version. Moreover, the limitation to five-minute running time posed a problem – no luxury of screen time to allow the kids ample opportunity to get their tracing in. Viewing the episodes and attempting to imagine the task of following the verbal instructions given to the kids to the letter, one can only suppose that anyone who actually completed all the drawings requested in an average episode truly deserved the title of “quick on the draw”. The revival thus didn’t last long – about one season – and subsequently disappeared without a trace, excepting a fairly rare DVD package containing only a portion of the total episodes produced. (I believe you still had to send away separately to obtain magic screens for the DVD!)

Parents’ complaints are believed to some degree to have been behind the ultimate demise of the show. And yet, in 1969, history would repeat itself, as the idea was hatched to revive the series in color, as syndicated stand-alone five-minute cartoons with reasonable animation but low budgets, produced by Fred Calvert. Lionel Wilson would be hired to dig out of moth balls his old voices from the “Tom Terrific” series for Terrytoons, which became interchangeably used in the new series (Tom’s voice for Winky, and Mighty Manfred’s voice for Winky’s dog Woofer). Even a villain or two in the new series didn’t sound far from the voice of Crabby Appleton. While an array of ideas were devised for using the shape-tracing gimmick, leading to a good many sales of new magic screen kits in local Toys “R” Us outlets, the color series generally lacked the inventiveness and spirit of its Tom Terrific ancestor, though certainly a step up from Winky’s 1953 version. Moreover, the limitation to five-minute running time posed a problem – no luxury of screen time to allow the kids ample opportunity to get their tracing in. Viewing the episodes and attempting to imagine the task of following the verbal instructions given to the kids to the letter, one can only suppose that anyone who actually completed all the drawings requested in an average episode truly deserved the title of “quick on the draw”. The revival thus didn’t last long – about one season – and subsequently disappeared without a trace, excepting a fairly rare DVD package containing only a portion of the total episodes produced. (I believe you still had to send away separately to obtain magic screens for the DVD!)

A sample episode from the color edition is embedded below.

Walt Disney was among the earliest contributors of quality animation to television, via special episodes of the “Disneyland” anthology series, and stock bumpers created for framing of the daily Mickey Mouse Club. Here, the Disney gang, who in their theatrical days rarely questioned the reality of their own existence, suddenly became ultra-conscious of their roles as TV stars.

Walt Disney was among the earliest contributors of quality animation to television, via special episodes of the “Disneyland” anthology series, and stock bumpers created for framing of the daily Mickey Mouse Club. Here, the Disney gang, who in their theatrical days rarely questioned the reality of their own existence, suddenly became ultra-conscious of their roles as TV stars.

Mickey, who had retired from the big screen in 1953, would be among the first animated characters to nominally “host” his own show, as “The leader of the club that’s made for you and me”. Along with a memorable theme song sequence, five daily sets of wraparound bumpers were filmed with dialogue, in which Mickey himself addresses the audience, “Hi Mouseketeers”, and tells us which day it is (Fun With Music Day”, Guest Star Day, Anything Can Happen Day, Circus Day, and Talent Roundup Day), then provides a brief wrap-up comment at the end of the show. (Other interstitials were filmed without dialogue, including a now infrequently-seen shot of Mickey cranking an animated newsreel camera with running tripod for the frequently deleted sequence, “The Mickey Mouse Newsreel”.) If the voice of Mickey sounds off in these bits, it’s for an unexpected reason. The voice is provided by Walt himself, coming out of retirement as the voice of Mickey, which he had ceased to provide following the production of “Mickey and the Beanstalk”. But his voice had darkened so considerably (reputedly from heavy smoking) that his falsetto didn’t register properly, and might have been helped if he had chosen to speed-up the recording tape, but did not. A version of the five opening intros, from color negatives not seen in the original broadcasts, with dialogue altered to remove the names of several of the days originally introduced, is presented below.

The Disneyland show would contribute numerous hour-packages of classic animation, formatted into semi-cohesive stories through full-budgeted bridging animation, generally provided by veteran Disney short directors Jack Hannah and Charles Nichols. Hamilton Luske also greatly contributed to this show, but his work was more typically aimed at new original character animation of the studio’s budding star emcee, Professor Ludwig Von Drake, who would appear later when the series changed its name to “The Wonderful World of Color”. Many of the pre-Ludwig hours were of quite notable quality. A standout among the early installments, regrettably one of the few to be filmed only in black-and-white, preventing later reuse of its sequences without computer colorization, was A Day In the Life of Donald Duck (2/1/56). This gem, typically known in the past only from rare screenings of brief clips, has recently come to light online in its most complete form, excising only those points where footage from previous theatrical cartoons were spliced-in. The program combines live-action and animation, tracking a typical day behind the scenes with Donald at the Walt Disney Studio. We enter Donald’s private office, complete with executive desk and chair, intercom, personal live attractive secretary, and a daily sack of fan mail. Donald begins to read through his letters in happy anticipation of complimentary remarks, when a particular note upsets him – a young viewer, who claims she can’t understand a word the duck says. Irate Donald decides something must be done about this and buzzes his secretary to send in his “voice”. This cues a rare on-screen appearance of Clarence “Ducky” Nash, the actual voice of Donald from his inception through “Mickey’s Christmas Carol”. Clarence enters, remarking that it’s a beautiful day for the little animals, allowing him opportunity to demonstrate various bird calls and animal impressions. Donald shows Clarence the note. Clarence has his own explanation for why the kids can’t understand Donald. “Must be that flat beak of yours – can’t mouth the words right.” Donald counters with “Why you pigeon-brain, you just don’t articulate.” “Oh yeah?” responds Clarence, lapsing into Donald’s voice, and reciting “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers.” “Fooey!”. snaps Donald, “Can’t understand it myself.” Clarence breaks into a ducky rendition of the “Davy Crockett” theme, complete with coonskin cap, generating from Donald the comment, “Oh, no.” The argument becomes more heated, as Clarence says Donald makes him sick, and Donald claims Clarence makes him twice as sick. The mathematics increase, until Clarence tells Donald to go jump in the lake. As Clarence exits into the corridor, Donald tries to have the last say, by giving Clarence a horse-laugh at the door. But Donald’s office phone rings, and on the other end is Clarence, with a final return of the horse laugh.

The Disneyland show would contribute numerous hour-packages of classic animation, formatted into semi-cohesive stories through full-budgeted bridging animation, generally provided by veteran Disney short directors Jack Hannah and Charles Nichols. Hamilton Luske also greatly contributed to this show, but his work was more typically aimed at new original character animation of the studio’s budding star emcee, Professor Ludwig Von Drake, who would appear later when the series changed its name to “The Wonderful World of Color”. Many of the pre-Ludwig hours were of quite notable quality. A standout among the early installments, regrettably one of the few to be filmed only in black-and-white, preventing later reuse of its sequences without computer colorization, was A Day In the Life of Donald Duck (2/1/56). This gem, typically known in the past only from rare screenings of brief clips, has recently come to light online in its most complete form, excising only those points where footage from previous theatrical cartoons were spliced-in. The program combines live-action and animation, tracking a typical day behind the scenes with Donald at the Walt Disney Studio. We enter Donald’s private office, complete with executive desk and chair, intercom, personal live attractive secretary, and a daily sack of fan mail. Donald begins to read through his letters in happy anticipation of complimentary remarks, when a particular note upsets him – a young viewer, who claims she can’t understand a word the duck says. Irate Donald decides something must be done about this and buzzes his secretary to send in his “voice”. This cues a rare on-screen appearance of Clarence “Ducky” Nash, the actual voice of Donald from his inception through “Mickey’s Christmas Carol”. Clarence enters, remarking that it’s a beautiful day for the little animals, allowing him opportunity to demonstrate various bird calls and animal impressions. Donald shows Clarence the note. Clarence has his own explanation for why the kids can’t understand Donald. “Must be that flat beak of yours – can’t mouth the words right.” Donald counters with “Why you pigeon-brain, you just don’t articulate.” “Oh yeah?” responds Clarence, lapsing into Donald’s voice, and reciting “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers.” “Fooey!”. snaps Donald, “Can’t understand it myself.” Clarence breaks into a ducky rendition of the “Davy Crockett” theme, complete with coonskin cap, generating from Donald the comment, “Oh, no.” The argument becomes more heated, as Clarence says Donald makes him sick, and Donald claims Clarence makes him twice as sick. The mathematics increase, until Clarence tells Donald to go jump in the lake. As Clarence exits into the corridor, Donald tries to have the last say, by giving Clarence a horse-laugh at the door. But Donald’s office phone rings, and on the other end is Clarence, with a final return of the horse laugh.

Next visitor to Donald’s office is Jimmie Dodd, along with a trio of studio musicians. (I wonder if anyone can identify the members of the trio – and I wonder if any of them are moonlighting from the “Firehouse Five Plus Two”.) Jimmie performs his latest composition, “Quack, Quack, Quack, Donald Duck”. The studio seems to have had high hopes of promoting the song as a new theme number for Donald, issuing at about the time of the broadcast a studio recording that would appear in the respective catalogs of Little Golden Records, Mickey Mouse Club Records, and Disneyland Records, yet has fairly little recognition today. The number is clever, and, though I can find no composer credit on most if not all issues of the record, probably was written by Dodd, given his prolific writing of music for the Mouse Club program. The visual presentation is highly creative, accompanied by supposed children’s drawings of Donald received from international settings around the world. Childlike drawings in semi-cutout animation this depict Donald as seen in the countries of Mexico, France, Switzerland, Italy, Poland, and even China. The “round the world” versions were closely followed on side 2 of the children’s record editions.

Next visitor to Donald’s office is Jimmie Dodd, along with a trio of studio musicians. (I wonder if anyone can identify the members of the trio – and I wonder if any of them are moonlighting from the “Firehouse Five Plus Two”.) Jimmie performs his latest composition, “Quack, Quack, Quack, Donald Duck”. The studio seems to have had high hopes of promoting the song as a new theme number for Donald, issuing at about the time of the broadcast a studio recording that would appear in the respective catalogs of Little Golden Records, Mickey Mouse Club Records, and Disneyland Records, yet has fairly little recognition today. The number is clever, and, though I can find no composer credit on most if not all issues of the record, probably was written by Dodd, given his prolific writing of music for the Mouse Club program. The visual presentation is highly creative, accompanied by supposed children’s drawings of Donald received from international settings around the world. Childlike drawings in semi-cutout animation this depict Donald as seen in the countries of Mexico, France, Switzerland, Italy, Poland, and even China. The “round the world” versions were closely followed on side 2 of the children’s record editions.

Donald next attends a story session with the studio writers, busy on a new storyboard for the duck. They greet Donald like a mighty studio mogul, offer him an easy chair, and pitch their story ideas. Fickle Donald tries to embellish a morning dawn scene with more birds, butterflies, rabbits, etc. The artists attempt to whip up new characters as fast as Donald can mention them, but things get out of hand when one of them pins on the board a long unrolling drawing of a giraffe. Donald changes his mind completely, blows all the drawings off the board, and insists on a film where he can star all by himself. The end result integrates the theatrical cartoon, Drip Dippy Donald.

The final half of the show is prompted by a call from Walt. The Moiseketeers are coming over for their first visit to the studio. Donald acts as tour guide, and is inducted into the Mouseketeers with an honorary duck-sized set of Mouseketeer ears. Donald ushers them past the sound effects department, or so he thinks, turning around to find the kids have ducked inside the set just as the door is closing shut for a recording session. A mock adding of effects is performed to the theatrical “Fire Chief”, then, as the studio door rises at the conclusion of the session, a stagehand throws out a large bucket of water used during the creating of the water sounds. It splashes on Donald standing outside the door – and washes the paint off Donald’s lower half, reducing it to ink outline. The only way to fix things? A trip to the ink and paint department. There, Donald hops onto a cel, and is repainted by one of the ladies presiding over the paint work. But Donald is embarrassingly hung out to dry on a clothesline, and asked to carry a sign in one hand reading “wet paint”. No, this is not a cue for the cartoon of the same name. Instead, the paint girl relates how in one film, only a pint of paint was needed for Donald instead of the usual gallons, leading to a showing of his invisibility comedy from WWII, “The Vanishing Private”. Finally, Big Roy Williams barges in on a reprise performance by all the Mouseketeers of the “Quack Quack, Quack” song, demonstrating some of his fast drawing, then introducing a screening for Donald and the Mouseketeers of Donald’s supposed latest completed picture, 1938’s Good Scouts.

The final half of the show is prompted by a call from Walt. The Moiseketeers are coming over for their first visit to the studio. Donald acts as tour guide, and is inducted into the Mouseketeers with an honorary duck-sized set of Mouseketeer ears. Donald ushers them past the sound effects department, or so he thinks, turning around to find the kids have ducked inside the set just as the door is closing shut for a recording session. A mock adding of effects is performed to the theatrical “Fire Chief”, then, as the studio door rises at the conclusion of the session, a stagehand throws out a large bucket of water used during the creating of the water sounds. It splashes on Donald standing outside the door – and washes the paint off Donald’s lower half, reducing it to ink outline. The only way to fix things? A trip to the ink and paint department. There, Donald hops onto a cel, and is repainted by one of the ladies presiding over the paint work. But Donald is embarrassingly hung out to dry on a clothesline, and asked to carry a sign in one hand reading “wet paint”. No, this is not a cue for the cartoon of the same name. Instead, the paint girl relates how in one film, only a pint of paint was needed for Donald instead of the usual gallons, leading to a showing of his invisibility comedy from WWII, “The Vanishing Private”. Finally, Big Roy Williams barges in on a reprise performance by all the Mouseketeers of the “Quack Quack, Quack” song, demonstrating some of his fast drawing, then introducing a screening for Donald and the Mouseketeers of Donald’s supposed latest completed picture, 1938’s Good Scouts.

Further episodes were produced in color (though originally aired in black and white, since ABC had not gone over to color-casting), and with one exception below are more recognizable to fans of the show due to their many reruns, and in at least two instances, VHS/Laserdisc releases. On Vacation (2/7/56) incurred some audio redubbing over the years, to remove Walt’s voice on the phone after the studio founder’s death. Jiminy Cricket is phoned by Walt (in a sequence combining animation and live action), and offered a chance to produce one of the program’s shows on his own. One thing above all he is cautioned about – watch the budget. Jiminy needs a script – but even more important, he needs actors. Hopping on the buttons of the studio intercom system, Jiminy tries to call in Mickey, Donald, Goofy, and Pluto, but finds they are all on vacation. Jiminy busily hops upon the keys of a typewriter to produce a working script for the show, while telephonically organizing a manhunt to track down the missing stars and return them to the studio. When the gang is finally reunited back at the office, they review Jiminy’s script, but reject it, expounding their own ideas for a program – which develops into a plot description of the classic “Hawaiian Holiday” in which they all appear. “There goes the budget” says a dismayed Jiminy to himself. As Mickey and cast reach the end of their plans for the story (told in cutaway to the 1937 cartoon), they find to their surprise that Jiminy is abandoning ship, leaving them to produce the show themselves, and depositing himself inside a postage-paid envelope addressed to Catalina, to transport him with the outgoing mail to his own vacation destination. From out of a flap cit below the postage stamp on the envelope, Jiminy pops his head out to express his final thoughts to the cast. “By the way, fellas, have a good show – but watch the budget.”

Further episodes were produced in color (though originally aired in black and white, since ABC had not gone over to color-casting), and with one exception below are more recognizable to fans of the show due to their many reruns, and in at least two instances, VHS/Laserdisc releases. On Vacation (2/7/56) incurred some audio redubbing over the years, to remove Walt’s voice on the phone after the studio founder’s death. Jiminy Cricket is phoned by Walt (in a sequence combining animation and live action), and offered a chance to produce one of the program’s shows on his own. One thing above all he is cautioned about – watch the budget. Jiminy needs a script – but even more important, he needs actors. Hopping on the buttons of the studio intercom system, Jiminy tries to call in Mickey, Donald, Goofy, and Pluto, but finds they are all on vacation. Jiminy busily hops upon the keys of a typewriter to produce a working script for the show, while telephonically organizing a manhunt to track down the missing stars and return them to the studio. When the gang is finally reunited back at the office, they review Jiminy’s script, but reject it, expounding their own ideas for a program – which develops into a plot description of the classic “Hawaiian Holiday” in which they all appear. “There goes the budget” says a dismayed Jiminy to himself. As Mickey and cast reach the end of their plans for the story (told in cutaway to the 1937 cartoon), they find to their surprise that Jiminy is abandoning ship, leaving them to produce the show themselves, and depositing himself inside a postage-paid envelope addressed to Catalina, to transport him with the outgoing mail to his own vacation destination. From out of a flap cit below the postage stamp on the envelope, Jiminy pops his head out to express his final thoughts to the cast. “By the way, fellas, have a good show – but watch the budget.”

Donald’s Award (2/27/57) is another rarely-seen hour of behind-the scenes tomfoolery, with a great deal of creativity, and especially well-rendered bridging animation closely matching the footage of theatricals integrated into the hour. Oddly, though known to have been rebroadcast at one point in color, only a black and white print from its first release has been shown in recent years. Walt has been receiving constant complaints about Donald’s behavior, and so has challenged Donald with the lure of an incentive to mend his ways. Installing a special complaint box in the studio, Walt makes an offer to Donald that if a week can elapse without receiving any complaint about Donald, the duck will win a fancy award certificate, displayed above the box upon the wall. Walt, however, wants to be doubly-sure that the duck’s record remains squeaky-clean, and so also enlists the services of Jiminy Cricket to play private eye, and tail the dick to investigate his activities during the week. Jiminy dons a Sherlock Holmes hat, and becomes all the more suspicious when not a single complaint seems to be hitting the complaint box. He thus travels to the residences of those most likely to have fraternized with the duck during the week, including Chip and Dale, Black Pete, Daisy Duck, and Pluto. The interview with Daisy is especially clever, having both cricket and duck deliver lines in low-toned underplay, spoofing the mood of an episode of Jack Webb’s “Dragnet”. All of the interviewees have plenty to say about complaints at what Donald has done to them (told through flashbacks to old cartoons), but their complaint notes never seem to have reached the studio box. Jiminy determines to find out why, and discovers that Donald has altered the wall behind the box to include a trap-door, allowing Donald to retrieve the complaints inside into his inner office, where he quickly tears each one to shreds for deposit n the wastebasket. Jiminy ruffles the feathers of the duck’s plan for vainglorious reward, by depositing into the box Donald’s proposed award certificate – which is quickly mangled in the manner of all the deposited complaints. Donald only discovers too late from the shreds of paper in his hand the lettering reading “Good Conduct Award”, and realizes his plan has backfired. Jiminy closes by landing on Donald’s bill, and singing the closing bars of his song from “Pinocchio”, “Always let your conscience be your guide.”

Donald’s Award (2/27/57) is another rarely-seen hour of behind-the scenes tomfoolery, with a great deal of creativity, and especially well-rendered bridging animation closely matching the footage of theatricals integrated into the hour. Oddly, though known to have been rebroadcast at one point in color, only a black and white print from its first release has been shown in recent years. Walt has been receiving constant complaints about Donald’s behavior, and so has challenged Donald with the lure of an incentive to mend his ways. Installing a special complaint box in the studio, Walt makes an offer to Donald that if a week can elapse without receiving any complaint about Donald, the duck will win a fancy award certificate, displayed above the box upon the wall. Walt, however, wants to be doubly-sure that the duck’s record remains squeaky-clean, and so also enlists the services of Jiminy Cricket to play private eye, and tail the dick to investigate his activities during the week. Jiminy dons a Sherlock Holmes hat, and becomes all the more suspicious when not a single complaint seems to be hitting the complaint box. He thus travels to the residences of those most likely to have fraternized with the duck during the week, including Chip and Dale, Black Pete, Daisy Duck, and Pluto. The interview with Daisy is especially clever, having both cricket and duck deliver lines in low-toned underplay, spoofing the mood of an episode of Jack Webb’s “Dragnet”. All of the interviewees have plenty to say about complaints at what Donald has done to them (told through flashbacks to old cartoons), but their complaint notes never seem to have reached the studio box. Jiminy determines to find out why, and discovers that Donald has altered the wall behind the box to include a trap-door, allowing Donald to retrieve the complaints inside into his inner office, where he quickly tears each one to shreds for deposit n the wastebasket. Jiminy ruffles the feathers of the duck’s plan for vainglorious reward, by depositing into the box Donald’s proposed award certificate – which is quickly mangled in the manner of all the deposited complaints. Donald only discovers too late from the shreds of paper in his hand the lettering reading “Good Conduct Award”, and realizes his plan has backfired. Jiminy closes by landing on Donald’s bill, and singing the closing bars of his song from “Pinocchio”, “Always let your conscience be your guide.”

Then there was the perennial Christmas hour, From All of Us To All of You (12/19/58). Mostly a chance for Jiminy again to host, with another new catchy song for the season, and some voiceless musical accompaniment by Mickey on piano, trumpet, bass, and drums, and Pluto on bells. No one seems to have the complete show viewable in one place. A reasonably accurate reconstruction of the original broadcast is presented below, substituting surviving color elements for footage first shown in black and white, and for reasons unexplained fast-forwarding through the excerpts from “Ladt and the Tramp”, “Cinderella”, and “Snow White”, which are separately viewable in other versions on the web. It may also possibly be inaccurate in including the “Mammy” black doll shot from “Santa’s Workshop”, which I would have supposed likely to have been censored and snipped as of the time of this show’s first airing. The reconstruction does, however, include the rarely seen live-action introduction by Walt himself, appearing on the mantelpiece in cricket size, with the explanatory punch-line, “Christmas is bigger than all of us.” It also thankfully does not cut out (which other edits online sometimes do) the final sequence, featuring a large group of Disney characters to listen to Jiminy’s rendition of “When You Wish Upon a Star” – his own “memorable moment”. The show seemed to appear in a different cutting each year, late broadcasts usually pushing the latest Disney feature with a screening of advance clips – even long after Cliff Edwards was deceased, resulting in several added voice-overs by unknown performers. In the days before VHS and DVD, this show was eagerly awaited each season for its vast array of classic Disney feature clips not otherwise viewable on small screen. By the time Jiminy uttered his final words, “From all of us, to all of you, Merry Christmas”, it never failed to warm my heart.

Then there was the perennial Christmas hour, From All of Us To All of You (12/19/58). Mostly a chance for Jiminy again to host, with another new catchy song for the season, and some voiceless musical accompaniment by Mickey on piano, trumpet, bass, and drums, and Pluto on bells. No one seems to have the complete show viewable in one place. A reasonably accurate reconstruction of the original broadcast is presented below, substituting surviving color elements for footage first shown in black and white, and for reasons unexplained fast-forwarding through the excerpts from “Ladt and the Tramp”, “Cinderella”, and “Snow White”, which are separately viewable in other versions on the web. It may also possibly be inaccurate in including the “Mammy” black doll shot from “Santa’s Workshop”, which I would have supposed likely to have been censored and snipped as of the time of this show’s first airing. The reconstruction does, however, include the rarely seen live-action introduction by Walt himself, appearing on the mantelpiece in cricket size, with the explanatory punch-line, “Christmas is bigger than all of us.” It also thankfully does not cut out (which other edits online sometimes do) the final sequence, featuring a large group of Disney characters to listen to Jiminy’s rendition of “When You Wish Upon a Star” – his own “memorable moment”. The show seemed to appear in a different cutting each year, late broadcasts usually pushing the latest Disney feature with a screening of advance clips – even long after Cliff Edwards was deceased, resulting in several added voice-overs by unknown performers. In the days before VHS and DVD, this show was eagerly awaited each season for its vast array of classic Disney feature clips not otherwise viewable on small screen. By the time Jiminy uttered his final words, “From all of us, to all of you, Merry Christmas”, it never failed to warm my heart.

The Adventures of Chip and Dale (2/27/59), unlike many of the preceding shows, has no real connecting plot, but presents the mischievous chipmunks as song-and-dance showmen, with a new and catchy theme song. Much of the action is again presented in a mix of animation and live action, with the two popping out of the shell of a large gift-wrapped walnut in the center of a studio desk. A tape recorder plays an audio introduction (likely featuring Walt’s voice in the original airing, but redubbed by the series announcer for later reuse). The introduction turns into a lengthy dissertation upon the life of the wild chipmunk – so boring it is putting Dale to sleep – until Chip whispers a suggestion into Dale’s ear. They climb upon the tape recorder, and change the playback speed, increasing the tempo until the taped voice zips through the dull lecture at chipmunk pitch in the twinkling of an eye. The chipmunks perform their song, playing among many of the desk’s items, including hopping upon the handle of a stapler, and a game of see-saw atop an ink blotter. Stories are told from a large storybook, including chapters on different pages for the multiple cartoons featured. Dale is repeatedly anxious to get to their Wild West epic, but can’t seem to find the right time to flip to the page – even stopped at one point by the pistol-packin’ hand of Pete himself, who gruffly informs him, “He said later, stupid.” The Western, the last of the duo’s starring vehicles under their own names, entitled “The Lone Chipmunks”, is finally shown, and the duo sing a farewell chorus of their song to the audience, returning to the walnut shell for the fade out.

The Adventures of Chip and Dale (2/27/59), unlike many of the preceding shows, has no real connecting plot, but presents the mischievous chipmunks as song-and-dance showmen, with a new and catchy theme song. Much of the action is again presented in a mix of animation and live action, with the two popping out of the shell of a large gift-wrapped walnut in the center of a studio desk. A tape recorder plays an audio introduction (likely featuring Walt’s voice in the original airing, but redubbed by the series announcer for later reuse). The introduction turns into a lengthy dissertation upon the life of the wild chipmunk – so boring it is putting Dale to sleep – until Chip whispers a suggestion into Dale’s ear. They climb upon the tape recorder, and change the playback speed, increasing the tempo until the taped voice zips through the dull lecture at chipmunk pitch in the twinkling of an eye. The chipmunks perform their song, playing among many of the desk’s items, including hopping upon the handle of a stapler, and a game of see-saw atop an ink blotter. Stories are told from a large storybook, including chapters on different pages for the multiple cartoons featured. Dale is repeatedly anxious to get to their Wild West epic, but can’t seem to find the right time to flip to the page – even stopped at one point by the pistol-packin’ hand of Pete himself, who gruffly informs him, “He said later, stupid.” The Western, the last of the duo’s starring vehicles under their own names, entitled “The Lone Chipmunks”, is finally shown, and the duo sing a farewell chorus of their song to the audience, returning to the walnut shell for the fade out.

This is Your Life, Donald Duck (3/11/60), in similar manner to Bugs Bunny’s “This Is a Life?”, lampoons and copycats Ralph Edwards’s “This Is Your Life” television show, with Jiminy Cricket as emcee. Only trouble is, the featured guest of honor, Donald, hasn’t shown up at the studio. He is still at home, and his nephews haven’t been able to get him to budge out of the house. Jiminy proposes a means to induce Donald’s cooperation, making reference to a poster on the studio wall of then-current Disney live-action hero, Zorro. Soon, Donald has a Z carved into his sailor shirt, as three masked Zorros (the nephews) force him to walk to the studio at sword-point. When Jiminy reveals tonight’s show is all about him, and he is on TV, Donald faints – but is finally propped up by the nephews in the seat of honor. Notables from Donald’s past are introduced, including Black Pete, Chip and Dale, and Daisy Duck – with a surprise appearance by Grandma Duck, in what may have been her only animated appearance, voiced by June Foray. The star-studded finale repeats the “Quack, Quack, Quack, Donald Duck” theme, and, while mostly compiled from retraced shots from numerous Disney features and shorts, probably presents the largest assembly of Disney characters to grace a single screen until 2023’s “Once Upon a Studio”.

This is Your Life, Donald Duck (3/11/60), in similar manner to Bugs Bunny’s “This Is a Life?”, lampoons and copycats Ralph Edwards’s “This Is Your Life” television show, with Jiminy Cricket as emcee. Only trouble is, the featured guest of honor, Donald, hasn’t shown up at the studio. He is still at home, and his nephews haven’t been able to get him to budge out of the house. Jiminy proposes a means to induce Donald’s cooperation, making reference to a poster on the studio wall of then-current Disney live-action hero, Zorro. Soon, Donald has a Z carved into his sailor shirt, as three masked Zorros (the nephews) force him to walk to the studio at sword-point. When Jiminy reveals tonight’s show is all about him, and he is on TV, Donald faints – but is finally propped up by the nephews in the seat of honor. Notables from Donald’s past are introduced, including Black Pete, Chip and Dale, and Daisy Duck – with a surprise appearance by Grandma Duck, in what may have been her only animated appearance, voiced by June Foray. The star-studded finale repeats the “Quack, Quack, Quack, Donald Duck” theme, and, while mostly compiled from retraced shots from numerous Disney features and shorts, probably presents the largest assembly of Disney characters to grace a single screen until 2023’s “Once Upon a Studio”.

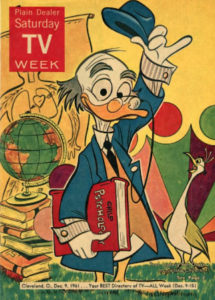

When Ludwig Von Drake finally came on the scene, in the premiere episode of the first season of The Wonderful World of Color, he came on with a bang. The half-hour segment, An Adventure in Color (9/24/61), consisted of entirely new animation (coupled with the theatrical Donald in Mathemagic Land to fill out the hour). It provided a brilliant tour de force for the unstoppable Paul Frees, who clowns and ad-libs his way in free-wheeling style with seemingly more verve than in any other subsequent appearance of the character (with the possible exception of a final cut on a Disneyland LP released at about the same time as Ludwig’s TV debut, in which the entire sketch appears to have been recorded impromptu, and is audibly heard to be cracking up even the musicians of the orchestra). Most notable in Ludwig’s eccentric dissertation upon the colors of the rainbow is a number called “The Spectrum Song”, which Ludwig plays upon an organ which somehow shoots out rays of varying color when its keys are pressed. Ludwig repeats the number, substituting gray tones for those still with black and white sets, so that they don’t feel left out. Then, a surprise gag arises, as a final chord producing multiple color rays suddenly separates from the organ, and is revealed to be the tail of the strutting NBC peacock. Ludwig accuses the vain bird of being a show-off, then whispers a secret to the audience. “Confidentially, he dyes his feathers.” The segment closes with a live-action montage demonstrating the rainbow of hues available in nature, underscored by the longest available rendition of the Sherman Brothers’ memorable theme song for the show, “The Wonderful World of Color.”

When Ludwig Von Drake finally came on the scene, in the premiere episode of the first season of The Wonderful World of Color, he came on with a bang. The half-hour segment, An Adventure in Color (9/24/61), consisted of entirely new animation (coupled with the theatrical Donald in Mathemagic Land to fill out the hour). It provided a brilliant tour de force for the unstoppable Paul Frees, who clowns and ad-libs his way in free-wheeling style with seemingly more verve than in any other subsequent appearance of the character (with the possible exception of a final cut on a Disneyland LP released at about the same time as Ludwig’s TV debut, in which the entire sketch appears to have been recorded impromptu, and is audibly heard to be cracking up even the musicians of the orchestra). Most notable in Ludwig’s eccentric dissertation upon the colors of the rainbow is a number called “The Spectrum Song”, which Ludwig plays upon an organ which somehow shoots out rays of varying color when its keys are pressed. Ludwig repeats the number, substituting gray tones for those still with black and white sets, so that they don’t feel left out. Then, a surprise gag arises, as a final chord producing multiple color rays suddenly separates from the organ, and is revealed to be the tail of the strutting NBC peacock. Ludwig accuses the vain bird of being a show-off, then whispers a secret to the audience. “Confidentially, he dyes his feathers.” The segment closes with a live-action montage demonstrating the rainbow of hues available in nature, underscored by the longest available rendition of the Sherman Brothers’ memorable theme song for the show, “The Wonderful World of Color.”

NEXT WEEK: We’ll move on into TV of the late ‘50’s from other studios.