Perhaps one of the greatest mysteries surrounding the cartoon world was the sudden rise of the Slow Burn Gag. Its reign of terror lasted a mere five years and can be likened to those collective phenomena that later prove implausible, such as the Dancing Plague of 1518. But the reality of the Plague was well documented, while the effectiveness that the Slow Burn may have had for our grandparents can only be assumed: difficult to verify, let alone explain. Even those for whom any animated piece produced since the 1960s is automatically junk, those who see sound as a dangerous innovation and are about to excommunicate even the movement itself, would have trouble justifying this fad.

What can be called a “Slow Burn Gag” in animation? I use the expression to refer to those cartoon sequences carefully built – slow and painfully – on the accumulation of mishap after mishap around a single repeated incident and produced in a timeframe roughly ranging from 1935 to 1940. A character – let’s say, Pluto the Dog or Barney the Bear – fails to perform a minimal task, usually taking a generous amount of time to (not) do so. Seen today, these gags usually produce in viewers – even among fans of the period – effects analogous to those shown on the screen. And yet in their time they were considered the apex of comedy, the pinnacle of animation; inseparable from the concept of “character animation”, the kind to which only the true professionals could access before the term became synonymous with endless dialogues.

Regarding its origins, some facts can be stated. It is clear that the Slow Burn owes much to the silent comedies in which armies of animators forged their sensibilities, in a gradual sophistication since the days of the Keystone Kops that made some names gain the authorial status necessary to free themselves from ass-kicking. Even during the early sound period, these gags were still the order of the day, to the despair of producers who resorted to all sorts of spurious musical tricks trying to cover up the lack of dialogue. However, it was one thing to see them on the hands of Edgar Kennedy or Oliver Hardy, and another to contemplate their literal versions in charge of drawn characters who could survive a safe falling on their heads.

At the time, Slow Burn was celebrated as a novelty in the face of the older song + parade scheme, both as a way to skip the stuck-to-the-beat animation, introducing breaks and rhythmic variations. But the reason that gave them fame in the studios was the feeling that through them they could endow their creatures with “personality”. At least in theory, since the reactions produced by a living spring or an insistent drop of water tended to be fairly homogeneous on screen.

Slow Burn had its heyday in the late 1930s: there may be earlier examples, but its birth certificate is the famous “flypaper sequence” in 1935’s Playful Pluto. Five or so years later it was six feet under, thanks to Tex Avery, Bob Clampett and other visionaries.

It is difficult to define this species by a clear taxonomy. Often confused with the “running gag”, the “extended gag” or just an elaborate gag, what differentiates the true Slow Burn from the rest is that it is deliberately insufferable, painful to watch, one would like to scream and can’t, etc.

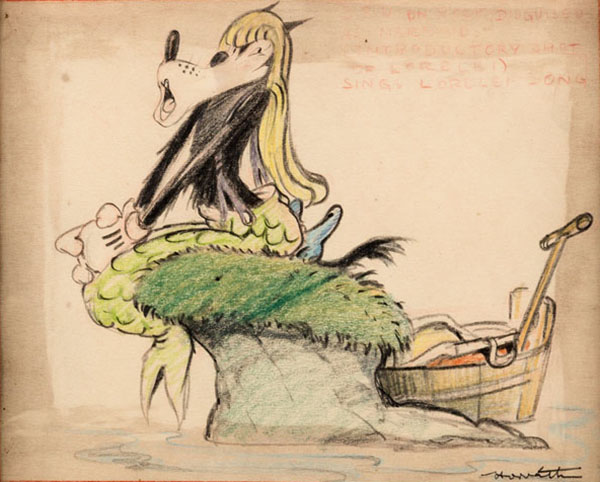

Difficult to define, perhaps, unmistakable when you have it in front of you; the Slow Burn is the equivalent of the jazz “solo”. Disney Studios specialized in it, and many of the Mickey, Goofy and Donald shorts are based on the formula: a joint presentation, separation of the members into three parallel SB for each one and a final reunion in a last scene that shows great production values, with hundreds of dishes, houses, whatever, flying through the air. But three short pieces are not the best exponents of their kind (the real thing is anything but short), and, after all, Pluto’s plight lasts only one minute fifteen seconds on screen. Nothing comparable to the eight solid minutes of The Bear That Couldn’t Sleep or the seven of Good Night, Elmer. The early Chuck Jones, Jones the Slow, was another of its cultists and in the films co-directed with Clampett it is easy to guess who directed what thanks to it. By then, Slow Burn meant “quality”, the sort of thing that gave Babbitt his reputation.

But let’s not be too hard on poor Slow Burn. Ultimately it was about a group of creators trying to push the envelope; just another case of the form falling in love with the form itself -a situation that may give us flawed works, perhaps, but that allows us to confirm that the medium is still alive and kicking. The only great bug of the Slow Burn was the same one that affected the later Film Noir as a genre: its predictability.

The big question, however, still remains: did anyone ever laugh at this kind of gags? Are there any documents that prove they ever moved the maxillary bones of any audience? A Preston Sturges’ film featuring a group of inmates laughing their heads off at the aforementioned flypaper scene would seem to prove that it did. And yet, it may well be a way to showing a group of thugs laughing at the corniest thing ever. “Sullivan’s Travels” is a work of fiction, after all.

Some of his contemporaries could see their weaknesses. One of Disney’s best artists, Hungarian designer Ferdinand Horvath, wrote, in a 1937 memo called “Surprise in Gags”: “The most effective gags are those that will take the audience by complete surprise. The absurdity of the situation is an important factor – Gags around convenient props that naturally lend themselves to gag situations are more or less anticipated by the audience. Take a sack of potatoes spilled on the cellar floor, and you will expect some character to take a spill when coming in contact with them. Flypaper ditto… precariously balanced dishes… garden rake to be stepped upon.

Add Pluto, plus skates, plus ice-and it takes no imagination to expect him to slide about, tumble, and do most of the things he actually did. Introduce Pluto and the flypaper and you know that he is apt to get tangled up with it. Anticipation gratified to the nth degree. Mickey with the overworked nipple gag is another example.

It has become more or less a rule to take any awkward character to place him near enough to something that might trip him, or punch him or cause him other bodily discomforts-the audience will anticipate such, and it will be dished out to them ninety-nine times out of a hundred. Referring to some outstanding gag sequences, which were also mentioned in the “gag tip sheet”, as for instance Pluto’s skating sequence, Mickey with the rubber nipple, and Pluto’s flypaper sequence-all of these in my modest opinion are only mildly funny as gags themselves…”

Horvath, besides being an artist whose drawings could be drooled over for hours, demonstrates in this memo an uncommon courage, if we take into account the fact that he was shooting directly at the hard core of the kind of stories that interested Disney by then. But there is another curious element attached to the rise of this species, even if we avoid the question of its lack of humor. The emphasis on slow, complex movements, the need to rest on every slight change of expression of the victim, the emphasis in realistic weight, the hundreds and hundreds of hyper-controlled drawings, all point to one crucial fact: Slow Burn was expensive, terribly expensive. So why produce a lavish good of dubious effectiveness? The notion goes against the Twelve Principles of Efficiency or the profits that any commercial enterprise expects.

Perhaps the answer lies in the continuation of the Horvath memo: “…but they do offer good chances to the animator. However it depends on the animation whether a sequence of this sort will appear funny or not.”

And that’s the question. My guess is that animators, along with directors and producers (especially those who had been animators at some point in their careers) bet on Slow Burn not because of audience reaction or screen results but because of what it offered them in terms of skills development: anyone who could animate one of these gags convincingly would be able to animate just about anything. The insane amount of control required to pull the rabbit out of the hat was a sort of master’s degree, and any smart producer knew that the funny side of the joke didn’t matter as much as training the monsters on whose backs an entire industry would rest. In this sense, the animation industry had more similarities with the medieval Guilds than with modern capitalism, or what we perceive as such (Hanna-Barbera and the like would later correct this situation).

It’s funny that the guy who, with good reasons, put Slow Burn out of its misery also cited Disney as an inspiration. For Tex Avery, his own “speed trend” began in The Tortoise and the Hare (1935). Disney had eggs in several baskets and made his choice. Much later, directors like Jones could draw on what they had learned in these five painful years in new equations that avoided the model’s worst pitfalls while taking advantage of its virtues. Indeed, the best exponents of his Road Runner series consist of more synthetic variations of Slow Burn combined with unexpected – but expeditious – resolutions. Just as Horvath suggested (quoted in this Jim Korkis post): “Good surprise gags, well timed, and not being touched off to order when the audience expects it—are laugh getters, because they keep you on edge in expectant mood, they keep you guessing and fool you in the end.”