It was VHS that helped bring Fantasia 2000 to the screen. In 1991, Walt Disney’s original animated masterpiece Fantasia was released on VHS and sold 14.2 million copies worldwide.

It was VHS that helped bring Fantasia 2000 to the screen. In 1991, Walt Disney’s original animated masterpiece Fantasia was released on VHS and sold 14.2 million copies worldwide.

A sequel to Fantasia was a passion project for Walt’s nephew, Roy E. Disney, son of Roy O. Disney. One day, over lunch, Roy E. Disney brought up the idea to Michael Eisner shortly after he joined Disney as CEO.

“I saw a look in Michael’s eye when I told him about Fantasia, and he said, ‘Yeah, that’s kind of an interesting idea,’” remembered Disney in a 1999 interview. “So, I tucked away his reaction and thought, ‘That was interesting, I can’t imagine previous administrations reacting that way.’”

After Fantasia’s successful release on VHS, Roy seized an opportunity: “I wrote Michael a little note and said, ‘Not only should we do the second Fantasia, but now we can afford it!”

The follow-up to Fantasia was put into production, signifying a true realization Walt Disney had for the original film. Fantasia, released on November 13, 1940, was unlike anything accomplished in film.

The film was released in a non-traditional motion picture format as a “roadshow attraction” (released to a limited number of theaters for a certain period). It also came with an intermission, was released in “Fantasound” (an early version of stereophonic sound), and programs were even provided to audiences.

Walt also had other unique plans for Fantasia, as author John Culhane noted in his book Fantasia 2000: Visions of Hope:

Walt also had other unique plans for Fantasia, as author John Culhane noted in his book Fantasia 2000: Visions of Hope:

“’It is our intention to make a new version of Fantasia every year,’ said Walt Disney in 1940. ‘Its pattern is very flexible and fun to work with – not really a concert, not a vaudeville or a revue, but a grand mixture of comedy, fantasy, drama, impressionism, color, sound and epic fury.’”

However, when Fantasia didn’t fare well at the box office, these plans for future Fantasias were put aside. But, as years went on and Fantasia went through re-issues at theaters, the film gained renewed appreciation from many who saw it as innovative. By the time Fantasia had its successful home video release, it was appreciated as a masterpiece.

The sequel, initially entitled Fantasia Continued, before eventually being retitled Fantasia 2000 for its release at the start of the new millennium, was initially to include several segments from the original along with new sections.

In the end, however, only the iconic “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” with Mickey Mouse would return, surrounded by all new musical animated moments.

The film would open with Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Symphony Number 5,” a surreal sequence directed by Pixote Hunt that featured triangular shapes that mimic butterflies and bats, swarming against a backdrop of light that drips and flashes through clouds.

This was followed by “Pines of Rome” by Ottorino Respighi, which is the backdrop for whales being summoned by a nova, bursting from the water, and taking flight into the night sky.

“I said, ‘I don’t know what we’re going to do, but let’s just think about it. Let’s make it a fantasy of some kind.’” recalled director Hendel Butoy in 1999, discussing how the concept came about. “One of our artists then went and drew what a child might see in the shapes of clouds in the sky. She drew one sketch that had a whale in the clouds. From that sketch, we said, ‘Well, that’s an image that we’ve never seen before.’”

“Rhapsody in Blue” by George Gershwin was next on the program. Directed by Eric Goldberg, the animation here was in the style of legendary caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, who influenced Aladdin, thanks to Goldberg, a great admirer of Hirschfeld’s work.

Set in 1930s Manhattan, the segment focused on four characters trying to realize their dreams. Goldberg, who worked on the segment with his wife Susan, who served as art director, said that it turned out exactly how they conceived it. “We got something on the screen that really feels like our vision,” noted Goldberg in ‘99. “And we did it with the studio’s blessing.”

The next segment was set to “Piano Concerto No. 2,” by Dmitri Shostakovich, and it tells the tale of The Steadfast Tin Soldier by Hans Christian Andersen.

Disney had almost adapted the story in the late thirties and early forties, and conceptual artwork created for this unproduced film was still in the Studio’s Animation Research Library.

“Roy brought in the music and asked, ‘Is there anything worthwhile here?’” remembered Butoy, who also directed this segment, adding, “We put the sketches together as a story reel, and everybody looked at it. It was unanimous: we should do this. It was just kind of serendipitous that those sketches were done back then, and now it’s come around. It’s one of those happy coincidences.”

Next up was “The Carnival of the Animals” by Camille Saint-Sans as the backdrop for the tale of a flamingo who gets a hold of a yo-yo. “I needed a reason for [the flamingo] to have a yo-yo,” said Goldberg, who also directed this sequence. “Originally, he just finds it, and all of the other flamingos chase him, not unlike the ostriches chasing the one with the grapes in ‘Dance of the Hours.’ I felt that it was too similar to ‘Dance of the Hours,’ so I decided to change the dynamic and just make him the goofball that just doesn’t want to get in line. He just wants to do his yo-yo tricks and be left alone, thank you very much. Of course, the others don’t like that because they have a mob mentality.”

This was followed by the return of “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” after which a segment served as a vehicle for Donald Duck, set to “Pomp and Circumstance” by Sir Edward Elgar. In this section, Donald plays Noah’s assistant and tries to get two of each animal onto the ark before the flood. But, in the process, he and his true love, Daisy Duck, get separated and try to find one another.

“The whole thing being done in pantomime really lent itself to Donald,” said the segment’s director Francis Glebas in 1999. “It was actually like doing a silent film, only it was much trickier because if we made a little change, the music didn’t change, so you had to come up with new ‘bits of business’ to stick in where the old ‘business’ was.”

The conclusion for Fantasia 2000 was the dramatic “The Firebird Suite” by Igor Stravinsky. The segment, about a sprite who accidentally wakes the Firebird, a mammoth bird made of flames and lava, emerging from a nearby volcano, was directed by twin brothers Paul and Gaëtan Brizzi, who had helmed segments of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, at the Studio’s Paris facility.

Just before the film’s release, Paul Brizzi said, “Our goal was to create a visual poem, using the expressions of the characters to convey this. It’s a tribute to nature and how it can be so beautiful and so powerful and dangerous and unpredictable. It’s really a message of hope, especially at the end of the millennium.”

Throughout Fantasia 2000, each segment was introduced by a different guest star, including Steve Martin, Itzhak Perlman, Quincy Jones, Bette Midler, James Earl Jones, Penn & Teller, and Angela Lansbury. Don Hahn directed these sections.

Throughout Fantasia 2000, each segment was introduced by a different guest star, including Steve Martin, Itzhak Perlman, Quincy Jones, Bette Midler, James Earl Jones, Penn & Teller, and Angela Lansbury. Don Hahn directed these sections.

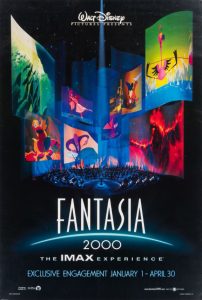

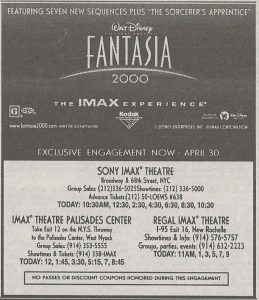

Like the original Fantasia, the sequel had a very unique release. It premiered on December 17, 1999, at Carnegie Hall as part of a five-city concert tour. Fantasia 2000 then opened on New Year’s Day 2000, exclusively at IMAX theaters, where it played for a four-month limited engagement through April 30. This was followed by a brief hiatus, after which Fantasia 2000 opened in theaters everywhere that summer on June 16, 2000.

Now, as it’s about to celebrate its 25th anniversary, Fantasia 2000 can be seen as a movie that brought Disney’s incredible animation renaissance period to an impressive crescendo and carried on a rich history and legacy that began with Walt.

It certainly was a shining moment for Roy E. Disney, who we sadly lost in 2009. He had shepherded the production throughout its journey, as so much changed at Disney. Just before the release of Fantasia 2000, Roy reflected on the comeback Disney animation had just experienced during the 90s by saying, “Maybe the public wanted it to happen, in a way. I think, maybe, they missed it.”