Many of us are still mourning the loss of animator/educator/historian Howard Beckerman, who passed away in June at age 94. I was doing some research at CalArts library last month and noticed they had bound volumes of Filmmakers Newsletter sitting on their shelves. I then remembered that Howard had a regular column (“Animation Kit”) in this magazine – a New York publication catering to the local filmmaking community there in the 1970s. I poured through the volumes and was delighted to re-read Howard’s pieces – and I thought readers of Cartoon Research might enjoy them too. I received official permission from his daughter Sheri Beckerman Weisz to repost them here – and I thank her for that. Today, I believe this is his first Animation Kit column from April 1972. Check in regularly to see more. – Jerry Beck

The other day I had lunch with Raoul Servais, a Belgian animator. Servais is a superior graphic artist. He has a distinct personal outlook on the world. His films “The False Note,” “Goldframe,” and “Operation X-70” reflect his concern for characterization and the social environment.

The other day I had lunch with Raoul Servais, a Belgian animator. Servais is a superior graphic artist. He has a distinct personal outlook on the world. His films “The False Note,” “Goldframe,” and “Operation X-70” reflect his concern for characterization and the social environment.

When asked about how he made the decision to enter the field of animation he replied, “I first became interested in animation when I was very young and first saw some old Felix the Cat cartoons. I couldn’t understand how the drawings moved and I studied the film, holding it up to my eye, a frame at a time.”

Felix the Cat and other denizens of the animated cartoon world have truly spread their influence far and wide.

The lifeblood of most animated films is the characters which romp through them. Each pen and ink character has a definite personality that audiences can relate to. Once a character becomes known, movie-goers automatically await the turn of plot that will reveal his or her special traits. Popeye has his raspy voice and his inevitable can of spinach. Who would buy a used car from wise guys Heckle and Jeckle or Bugs Bunny? The very sound of the phrase “What’s up Doc?” delivered with that familiar Brooklyn accent is enough to remind us that we are in the presence of an overpowering personality. Mr. Magoo and Gerald McBoing-Boing both prove that poor eyesight or a speech idiosyncrasy should not stand in the way of one’s popularity. Then of course there’s Olive Oyl’s good looks.

The oldest known cartoon personality is Gertie the Dinosaur, a character of Gargantuan proportions but with the attitudes of a puppy dog. Mutt and Jeff and Barney Google also appeared in animated cartoons after achieving popularity as newspaper comic strips.

The oldest known cartoon personality is Gertie the Dinosaur, a character of Gargantuan proportions but with the attitudes of a puppy dog. Mutt and Jeff and Barney Google also appeared in animated cartoons after achieving popularity as newspaper comic strips.

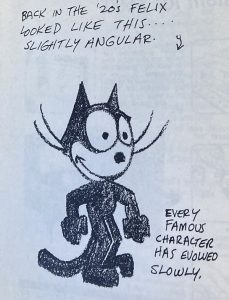

The first big-time cartoon star was Felix the Cat. Felix was created in 1919 and went through several years of evolutionary change to become the Felix that we know. Felix was animated originally by Otto Mesmer for Pat Sullivan. Sullivan before his death in the thirties became world famous for the Felix character. Mesmer is still active as an animator and is responsible for the cartoons on the animated sign in New York’s Times Square.

Joseph Oriolo who drew the Felix comic strip for many years, starting in the fifties, also produced a series of 250 Felix cartoons for television.

In order to decipher the secret of Felix’s appeal I went to see Joe Oriolo and view part of his library of early 1920’s Felix films.

Click images to enlarge.

I was surprised that these so-called “old” cartoons were no longer old. Instead, they were somehow new all over again. Perhaps this was because of the current interest in old cartoon styles, or because our mode of dress is much like the styles of Felix’s time? Could it be because the strength of a character comes through no matter what the age of its manufacture? After all, wasn’t Felix the inspiration for Disney’s Mickey Mouse and all that was to follow?

I decided that Felix is loved because he is pure “Cartoon.” He is the embodiment of the cartoon medium before it took on the likeness of reality. Felix is the great inkblot that comes to life. He is pure animation. Even Max Fleischer’s great KoKo the Clown needed a live person to augment his adventures.

If you are in the throes of creating a character, reflect on those cartoon personalities of the past:

Give your character a distinctive voice like Donald Duck’s, a memorable vocal expression like Bugs Bunny’s, a strong “prop” like Popeye’s spinach, and for action give your character the bounce of the early Mickey Mouse. Above all, keep your character simple and endow it with the inventiveness of Felix.

HOWARD BECKERMAN has worked in the animation field for enough years to have served as Storyman, Designer, and Animator for such studios as UPA, Paramount, and numerous other TV commercial enterprises. He is presently engaged in the creation of films for television and the teaching of animation at the Parsons School of Design and is Animation Editor of the Filmmakers Newsletter.