I’m hard-pressed to figure out a ‘hook’ for this article. Howard Beckerman fits into numerous peg-holes, one being “animator”, so let me start there.

I’m hard-pressed to figure out a ‘hook’ for this article. Howard Beckerman fits into numerous peg-holes, one being “animator”, so let me start there.

. . . HAH! If only it were that simple! Because Howard Beckerman mostly made TV commercials, which do not have credits. Thus, Howard leaves scant on-line footprint as an animator. He does turn up in some documentaries speaking on the subject of old cartoons. You can also find him quoted in books, the one he wrote, and the ones with interviews he did. It’s not that he isn’t well known. He is, but for what exactly?

About a decade ago I became interested in New York City’s animation history, and on that path all roads lead to Beckerman. How many books is he cit-ed in? Magazine articles? Documentaries?

But it’s usually talking points, because the interviewer is focused on a specific time and place or project. “What was it like at UPA?” . . .

I’ve interviewed Howard Beckerman myself a bunch of times. A nice guy, but unless he suddenly goes postal with an axe, that doesn’t help much with my hook. Frankly, I’m perplexed, so it’s probably better to have Howard tell you his story in his own way.

Bob Coar: Okay, Howard, where did you grow up?

Bob Coar: Okay, Howard, where did you grow up?

Howard Beckerman: Near the end of 1930 I was born in the Bronx, but just before I turned six years old, we moved to Flatbush, in Brooklyn. I had started Kindergarten in the Bronx, at P.S. 90, but completed it at P.S.181 in Flatbush. At the end of the first day in this new environment, each student took a partner and lined up to exit the class uniformly. I was the new kid and I had no partner, but I noticed a tall boy standing alone at the end of the line. I walked over to him and asked him his name. “Sandy,” he replied. Together we followed the class out the door. Today, 86 years after, Sandy and I are still close friends.

We moved to Brooklyn because my parents, after closing one business, had purchased a candy store. Though I hadn’t learned to read yet, the store offered a new world of comic books to browse. Famous Funnies, the first official pulp comic, had been published two years before. Here I was, scanning through Detective Comics before Batman, and was also there in June 1938 the moment that Superman arrived. I was outside the store when an older boy exited with his purchase, Action Comics number one. The magazine’s cover featured a costumed man hoisting a green automobile and smashing it against a rock formation. This kid had opened the magazine and responded to what he was seeing there, “Hey, this guy does everything!”

BC: And that made you want to become an animator?

Pinocchio Movie Poster (1940)

BC: I imagine it was a very different world back then?

HB: In the late 1940s there were about 18 newspapers in New York City. Some had morning, afternoon and evening editions. Over the next few years I began picking up tidbits, mostly from Disney promotional articles in magazines and daily newspapers. More instructive were the occasional article in publications such as Popular Science or Popular Mechanics that explained the “magic of the movies.” From these I acquired a closer understanding of the techniques of effects and animation.

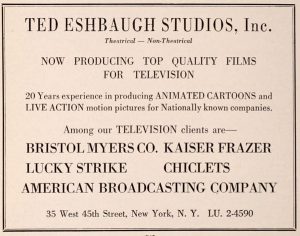

On a Friday afternoon in 1946, riding the subway from Manhattan back to Flatbush, I noticed a man reading the afternoon edition of The World Telegram, There was an article, the final one of a weeklong series about moviemaking in the New York area. It was titled, “Hollywood on the Hudson.” That day’s article was related to animation production. Three studios were highlighted: Famous Studios which was animating Popeye and Casper the Friendly Ghost cartoon shorts, the Ted Eshbaugh Studio which had done a series of Captain Cub cartoons and the Terrytoon organization which was known for Gandy Goose and Mighty Mouse. The important thing about this article, for me, was to discover that these studios were local. Famous and Ted Eshbaugh were next door to each other on 45th Street in Midtown Manhattan and Terrytoons was just above NYC in New Rochelle. I made it a point to visit the 45th Street location to stand outside the buildings. I looked up, and on the second floor of 35 West, I saw, through a window, the corner of a desk with an attached gooseneck lamp. My first ever view of a working animation studio! Many years later when my own small studio occupied space in some of these buildings I would jokingly tell visitors that I never looked out the window. They would ask why and I would say, “Because there might be some kid looking up.”

On a Friday afternoon in 1946, riding the subway from Manhattan back to Flatbush, I noticed a man reading the afternoon edition of The World Telegram, There was an article, the final one of a weeklong series about moviemaking in the New York area. It was titled, “Hollywood on the Hudson.” That day’s article was related to animation production. Three studios were highlighted: Famous Studios which was animating Popeye and Casper the Friendly Ghost cartoon shorts, the Ted Eshbaugh Studio which had done a series of Captain Cub cartoons and the Terrytoon organization which was known for Gandy Goose and Mighty Mouse. The important thing about this article, for me, was to discover that these studios were local. Famous and Ted Eshbaugh were next door to each other on 45th Street in Midtown Manhattan and Terrytoons was just above NYC in New Rochelle. I made it a point to visit the 45th Street location to stand outside the buildings. I looked up, and on the second floor of 35 West, I saw, through a window, the corner of a desk with an attached gooseneck lamp. My first ever view of a working animation studio! Many years later when my own small studio occupied space in some of these buildings I would jokingly tell visitors that I never looked out the window. They would ask why and I would say, “Because there might be some kid looking up.”

Shortly after this discovery, I went up to the Eshbaugh studio at 35 West 45th Street. As I spoke with a receptionist I noticed, through a partially opened door, an animator at a desk. I asked about the possibilities of getting a summer job there. The response was that I should stop by again and bring samples of my work.

I was 16 years old and studying cartooning and illustration at The High School of Industrial Art in Manhattan. I had not yet completed enough work that I considered showable. I didn’t go back to Eshbaugh, but the idea of working towards a serviceable portfolio became a strong goal.

I was 16 years old and studying cartooning and illustration at The High School of Industrial Art in Manhattan. I had not yet completed enough work that I considered showable. I didn’t go back to Eshbaugh, but the idea of working towards a serviceable portfolio became a strong goal.

BC: So how did you get started in the business?

At graduation, my illustration teacher, Ben Clements, made an appointment for me with Paul Terry. I had been stopping by various commercial art studios in town and each time I saw what they did there, I realized more and more that I preferred animation. By now I had a portfolio of the kind of cartoon drawings that I enjoyed doing. Terry was pleased with what he saw. Terry had a fatherly presence. We conversed and he answered my questions. I started work there the very next day.. That was 1949.

Okay, so that’s as far as Howard and I got on that interview project before we drifted away to other things. Sadly, the following notice from Howard’s daughter Sheri was just forwarded to me:

My father, Howard Beckerman, passed this morning, June 29, at 3:30 am.

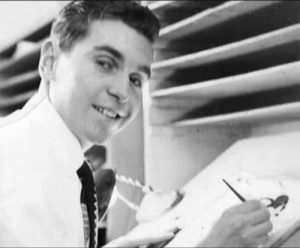

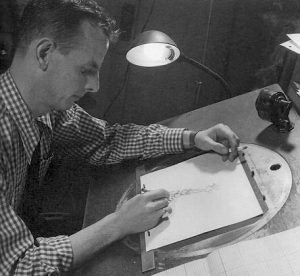

Howard at Terrytoons

Howard recalled animator Al Chiarito starting out at Terrytoons right after he did. There was a female animator named Muriel Gushue. Howard developed a crush on Mannie Davis’s daughter. Sixty years later he’d tell her about it at an event in White Plains.

The commute from Brooklyn to Terrytoons in New Rochelle wasn’t easy. Terrytoons stayed in New Rochelle that year when it moved from the Pershing Building into a former Knights of Columbus meeting hall on Centre Avenue. During the move Howard took an animation class taught by Irv Spector at one of the colleges. Spector worked at Famous Studios since the place was Fleisher Studios, and got Howard a job inbetweening at Famous.

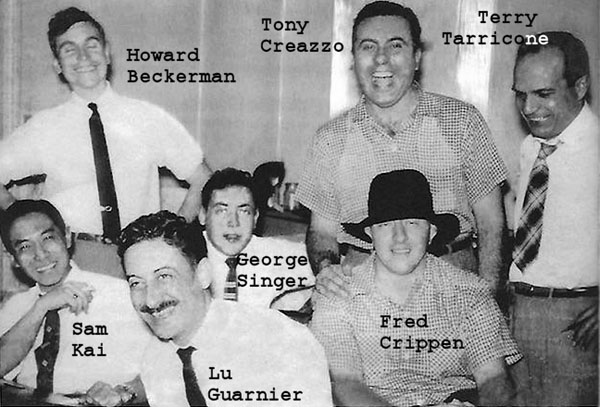

The Famous inbetweeners pool fit Howard like a glove. They paid union wages there. Inbetweeners earned $2.00 an hour. Other inbetweeners coming in included Fred Surace, Truman Parmalee and Jack Dazzo. The list of animators they worked for is impressive, including Bill Tytla, considered by many of that day to be the greatest living animator. Al Eugster, John Gentilella, Steve Muffati, Chuck Harriton, Bill Hudson, Bill Henning, Larry Riley, Gordon Whittier, Tony Creazzo, and Larry Riley animated as leads or assistants.

The Famous inbetweeners pool fit Howard like a glove. They paid union wages there. Inbetweeners earned $2.00 an hour. Other inbetweeners coming in included Fred Surace, Truman Parmalee and Jack Dazzo. The list of animators they worked for is impressive, including Bill Tytla, considered by many of that day to be the greatest living animator. Al Eugster, John Gentilella, Steve Muffati, Chuck Harriton, Bill Hudson, Bill Henning, Larry Riley, Gordon Whittier, Tony Creazzo, and Larry Riley animated as leads or assistants.

Al Eugster educated Howard on how to properly fill out exposure sheets. Irv Spector would stop by Howard’s desk and share tips about animation, as well as how to write a good cartoon story. Irv Specter was very involved with the Screen Cartoonists Guild, and Howard paid attention to union activities.

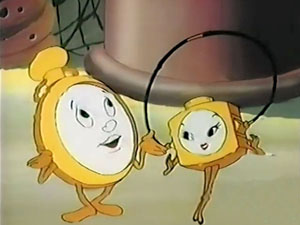

Howard Beckerman must have worked on dozens of Famous Studios cartoons, such as Popeye and Caspar, always as an uncredited Inbetweener. The only one we can identify is the Noveltoon, Land of Lost Watches . There was also sometimes moonlighting work at smaller shops. Moonlighting money turned out to be better. Howard interviewed for a slot at some of the smaller studios.

Howard Beckerman must have worked on dozens of Famous Studios cartoons, such as Popeye and Caspar, always as an uncredited Inbetweener. The only one we can identify is the Noveltoon, Land of Lost Watches . There was also sometimes moonlighting work at smaller shops. Moonlighting money turned out to be better. Howard interviewed for a slot at some of the smaller studios.

UPA was setting up a New York branch in 1951. That Hollywood studio had just won the Animated Short category at the Oscars with Gerald McBoing Boing. Hot on a roll, UPA intended to get big into east coast animated commercials. As Howard tells it:

When UPA opened the NY office in 1951 Abe Liss was the art director and I went up to see him. They were still building the offices. There were two people sitting there at animation desks. I didn’t know who they were but I found out later the older guy was Grim Natwick. The younger guy was Don McCormick, his assistant.

Natwick gave Howard some pencils bearing the UPA logo and told him to come back later.

The old crowd from the School of Industrial Arts still got together. Among them was Iris Funk, now working as a fashion illustrator in the Garment District. Iris’s other passion was dance. She wasn’t so impressed with animation until seeing GERALD McBOING BOING. She realized the medium’s potential to entertain adults. The crowd met at the beach where Iris talked to Howard about art and philosophy. She signed up for a class he was taking at the Art Students’ League. They became each other’s Muses.

Around the winter holidays in 1951 the Army Draft Board sent Howard a notice that he would be inducted. He left Famous Studios to prepare. Howard bumped into Ben Harrison, who offered him a job, which Howard felt compelled to turn down, but then his induction got indefinitely delayed. He started looking for a new job.

Shamus Culhane Productions put Howard on staff as an inbetweener. It may not have hurt that during the war Culhane’s animation supervisor Rod Johnson had been Irv Spector’s commander at the Army animation facility in Astoria. Regardless, being on Shamus Culhane’s payroll was both an honor and an Ivy League education. Shamus had started out at age sixteen under Walter Lantz’s tutelage. He put up with Charles Mintz to ink Krazy Kat before joining Fleischer Studios. At Fleischer’s he did the first Betty Boop toons alongside Grim Natwick and Al Eugster. Those three fellows would all work on SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS at Disney. They were together knocking out the best toons to come out of Ubbe Iwerks’ shop. Culhane, Eugster and Natwick were all in Miami for the two Fleischer feature films. Shamus knew many stories and tricks of the trade.

Willis Pyle

After the war Willis Pyle was part of Oscar Productions, which boasted Abe Liss doing layouts, while Norman McCahe, Emery Hawkins, Harry Love. Cal Dalton, and other luminaries animated beside Willis Pyle. They made one Cartoon and then Walter Lantx bought the company. Pyle bounced over to UPA, where he helped Hubley give birth to MISTER MAGOO. Willis Pyle worked on GERALD McBOING BOING not too long before he relocated to New York to get in on that fast TV commercial money.

The Army took Howard Beckerman in early 1952. While in basic training Howard married Iris Funk. Many of the animators were being assigned to the Astoria unit in Queens, or placed in cushy jobs illustrating training manuals and such. I asked Howard about that and he named a few instances, then, after a well-timed comedic pause he said – “They sent me to Korea!”

I asked him what he did there and Howard said he painted signs, submitted cartoons to STARS AND STRIPES, and stood a lot of guard duty. He said he never really engaged in combat, so I asked if he ever got shot at. Howard laughed and said “All the time! Sometimes by our own guys. Somebody was always shooting at something.” One day a jeep pulled up while Howard was on guard duty. Another infantryman relieved him of the post and Howard was whisked off to 2nd Division Headquarters, where he finished out his tour illustrating part of a book on that unit’s history.

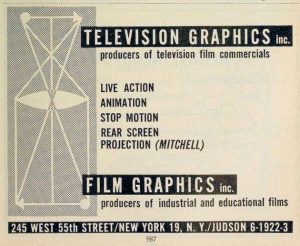

Howard Beckerman was safely back in New York by the end of 1953, freelancing as an inbetweener for $2.40 an hour. At the time, Lee Blair ran two studios out of the DuArt Building at 245 West 55th Street: Television Graphics specialized in commercials, while Film Graphics handled industrial and educational projects.

Howard Beckerman was safely back in New York by the end of 1953, freelancing as an inbetweener for $2.40 an hour. At the time, Lee Blair ran two studios out of the DuArt Building at 245 West 55th Street: Television Graphics specialized in commercials, while Film Graphics handled industrial and educational projects.

The owner, Lee Blair, had been with Disney, where his wife Mary Blair was one of Walt’s favored color designers. Lee’s brother Preston Blair worked on FANTASIA, and was often around. Film Graphics got busy with clients like the U. S. Information Service. Howard Beckerman was hired freelance to inbetween beside Vince Cafarelli, Ed Smith, and Fred Mogub. They worked under animators Ken Walker (another Disney guy) and Lu Guarnier (once an assistant animator for Leon Schlessinger). The Animation Supervisor Don Towsley had worked on three Disney features, so the whole shop had a Disney feel.

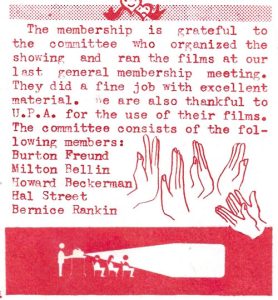

Lu Guarnier would bring a projector from Film Graphics to union meetings to showcase recent films produced by member studios. Howard volunteered to be on the committee overseeing that activity. He and Iris were expecting a child early in 1954, just as work slowed at Film Graphics and the inbetweeners were laid off. Howard moved over to Bill Sturm Studios.

Lu Guarnier would bring a projector from Film Graphics to union meetings to showcase recent films produced by member studios. Howard volunteered to be on the committee overseeing that activity. He and Iris were expecting a child early in 1954, just as work slowed at Film Graphics and the inbetweeners were laid off. Howard moved over to Bill Sturm Studios.

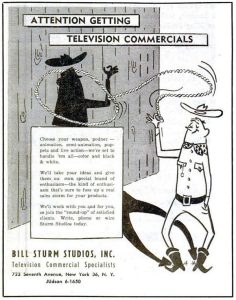

Bill Sturm was a New York fixture, having started at Bray Studios three decades earlier. Sturm animated Betty Boop and Popeye at Fleischer Studios, then briefly went to Disney. During the war Bill Sturm supervised animation for the Navy with Fletcher Smith Studios, opening his own shop in 1949 at 734 Broadway, down in Greenwich Village three blocks away from Washington Square Park.

Eventually Bill Sturm Studios made its way to midtown and the Times Square area. The Powers Building, 723 Seventh Avenue, claimed some prestige, having previously housed Walt Disney’s east coast office. Numerous industry related companies passed through there. Howard Beckerman found himself surrounded by animation history.

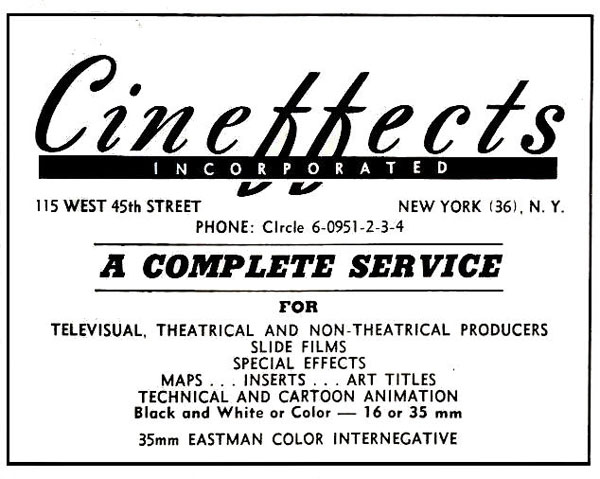

The Beckerman’s daughter Mara was born. Howard went over to Cineffects, one of the oldest general service studios in Manhattan. Cineffects was located at 115 West 45th Street, so Howard remained in the Times Square area. I don’t know what job position he held there, but in July 1954 Howard went over to UPA at 670 Fifth Avenue to assist George Singer in the Lay Out Department. Abe Liss was gone, leaving Gene Deitch in charge. UPA had a Coca-Cola commercial starring the character Madeline in production.

The Beckerman’s daughter Mara was born. Howard went over to Cineffects, one of the oldest general service studios in Manhattan. Cineffects was located at 115 West 45th Street, so Howard remained in the Times Square area. I don’t know what job position he held there, but in July 1954 Howard went over to UPA at 670 Fifth Avenue to assist George Singer in the Lay Out Department. Abe Liss was gone, leaving Gene Deitch in charge. UPA had a Coca-Cola commercial starring the character Madeline in production.

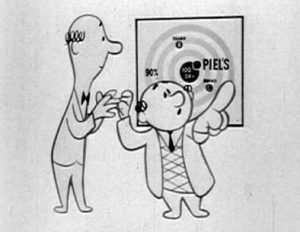

George Singer moved to Animator and Lu Guarnier replaced him as head of Lay Outs. After a bit Vince Cafarelli was hired to do layouts. Guarnier and Howard were placed in the Animation Department with desks near Grim Natwick. Howard hit the Betty Boop trifecta. UPA was a hot ticket, gathering praise over a series of Piels Beer ads starring the comedy duo Bob & Ray as brothers Bert and Harry Piels. The Museum of Modern Art, just down the block, recently dedicated a whole month to screening UPA commercials. Riding the subway, Howard would hear people talk snout commercials he’d contributed to. Other guests at dinner parties wanted to know more. At night he freelanced for Sutherland Television Films at 404 Fourth Avenue.

They had fun at UPA. Animator Tony Creazzo caused a bidding war between UPA and Sutherland Television Films and UPA that brought about raises for all. Once, they spotted comedian Ernie Kovacs across the street and had the gorgeous designer Edna Jacobs go out and convince Kovacs to take a tour of the studio. But in 1955 Sutherland shut down and Gene Deitch left UPA. Don McCormack became Studio Manager. The work rolled out.

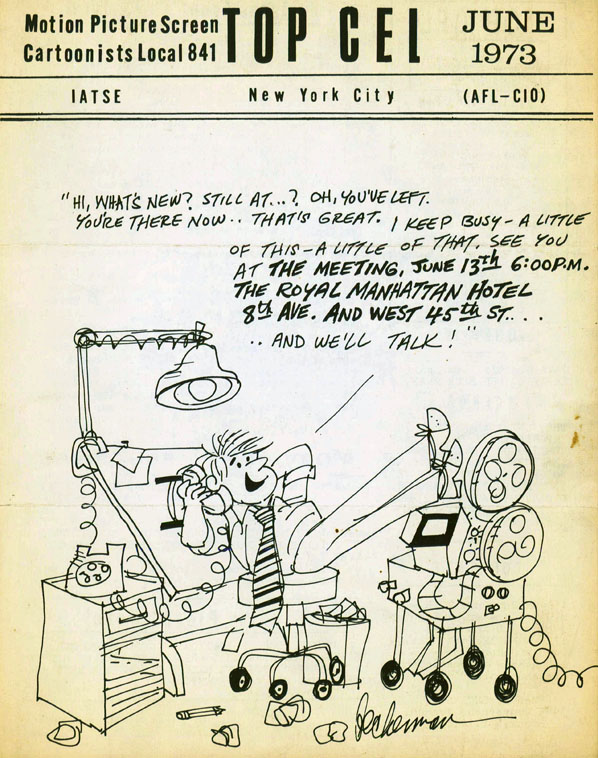

Howard was very active with the union and contributed art to the Top Cel newsletter. He campaigned to be editor of that newsletter in 1956, losing to incumbent Ed Smith. Howard did win the post of UPA’s union delegate, and a seat on the Steering Committee for the first annual animation film festival being organized at Fifth Avenue’s Hotel Pierre.

A pet-peeve of Howard’s was that many animators were either so ego-driven, or insecure, that they never complimented others on a job well done. One day Grim Natwick sat upright and announced to the room “I’m a great animator!”, leaving Howard to think ‘Great! Where does that leave the rest of us?’.

A pet-peeve of Howard’s was that many animators were either so ego-driven, or insecure, that they never complimented others on a job well done. One day Grim Natwick sat upright and announced to the room “I’m a great animator!”, leaving Howard to think ‘Great! Where does that leave the rest of us?’.

During 1957 Howard searched for a better fit, figuring UPA would always be there to go back to. Robert Lawrence, a dapper mogul, sent Howard to the more avant garde Ernest Pintoff. Howard took a job as New York animator for Detroit’s new Group Productions. Group’s founder Tully Rector went into Europe as a rifleman on D-Day. Moving to Paris after the war, he studied art on the GI Bill at the Academie Julian and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Group Productions commercials quickly became all the rage, and Howard made several trips to Detroit.

UPA’s New York office disbanded in 1958. Don McCormick formed a partnership with Roger Wade-at 15 West 46th Street. Wade had been a combat photographer stationed in China and Burma during the war. He’d established his general service studio in Times Square a dozen years since. McCormick traced back to Disney prior to UPA. He took the title Art Director at their new enterprise McCormick-Wade Animation. They hired Howard Beckerman. The shop didn’t last long and by 1959 Howard got picked up by Gene Deitch.

UPA’s New York office disbanded in 1958. Don McCormick formed a partnership with Roger Wade-at 15 West 46th Street. Wade had been a combat photographer stationed in China and Burma during the war. He’d established his general service studio in Times Square a dozen years since. McCormick traced back to Disney prior to UPA. He took the title Art Director at their new enterprise McCormick-Wade Animation. They hired Howard Beckerman. The shop didn’t last long and by 1959 Howard got picked up by Gene Deitch.

At a time when many little studios tried to present as trendy boutiques, Gene Deitch rented loft space above a furniture warehouse on the Upper West Side. He’d just come off a contentious stint as Creative Director of Terrytoons. Deitch brought Al Kouzel wiyh him as Animation Director. Writer Jules Feiffer tagged along. Ken Drake, who’d worked with Deitch at UPA, was production manager. Bill Ackerman, Gary Mooney, and Ed Seeman animated beside Howard Beckerman. During breaks these fellows stood at the window monitoring progress on construction of the Lincoln Center complex across the street.

1960 rolled around. Iris and Howard had a second daughter, Sheri. Gene Deitch got married and moved to Prague. Howard started freelancing. He ran for union president, ending up as V.P. to Wardel Gaynor, one of the first Black cameraman in the cartoon industry. Cullen Associates on 33 East 38th Street, the film wing of Xerox Corporation, put Howard Neckerman and Al Kouzel on staff.

When the CBS Television Network and the U.S. Department of Defense had movie star James Cagney narrate the anti-Communist documentary THE ROAD TO THE WALL in 1961, they tapped Howard Beckerman to animate the title. That June Howard returned to Bill Sturm Studios. The studio was in larger space at 49 West 45th Street, keeping busy making military films and commercials for clients such as Savings Bank Association of Massachusetts, Delco Batteries, Blatz Beer, and Firestone Tire.

Sturm had two dozen people on staff, including Sal Butta and Rudy Tomasseli. Don McCormiek was Vice-President in Charge of Production. Ken Walker acted as Animation Director. Orestes Calpini was Creative Head. John Vita painted Backgrounds. A few months after Howard showed up, Bill Sturm sold the studio and moved to Washington D.C.

Thrust back into freelancing, Howard Beckerman went to inbetween for Elektra Films at 33 West 46th Street. Phil Kimmelman, who’d started at Famous Studios just after Howard left, supervised Elektra’s animation department. Abe Liss, a founder, was Creative Director. Elektra Films had a reputation as a cutting edge studio.

Thrust back into freelancing, Howard Beckerman went to inbetween for Elektra Films at 33 West 46th Street. Phil Kimmelman, who’d started at Famous Studios just after Howard left, supervised Elektra’s animation department. Abe Liss, a founder, was Creative Director. Elektra Films had a reputation as a cutting edge studio.

Going into 1963, Howard continued freelancing, as well as writing articles for photography magazines. He also acted with the community theater in Forest Hills, taking the lead role in the play OUTWARD BOUND. Al Kouzel made a film for Otis Elevator with Howard Beckerman animating parts. Near the end of the year Howard took a job as writer/artist for Norcross Greeting Cards. When Crawley Films of Canada decided to make a sequel to THE WIZARD OF OZ, they contracted Rankin/Bass at 116 East 30th Street to do the animation. This was before Rankin/Bass became famous for their half-hour holiday specials. RETURN TO OZ was a feature-length cartoon airing on NBC.

Howard came on the project early, doing Continuity Design, Storyboard and Layouts. Animation was handled by old pros George Rufle, George Cannata, George Germanetti, and Milt Stein.

Howard came on the project early, doing Continuity Design, Storyboard and Layouts. Animation was handled by old pros George Rufle, George Cannata, George Germanetti, and Milt Stein.

Still freelancing, Howard Beckerman brought some story layouts he’d done to Paramount Cartoons, the saddest incarnation of Famous Studios. Howard Post was in charge. Beckerman left the boards there but never heard from Post. While making the rounds during 1966 Howard Bumped into Phil Kimmelman on the street, Beckerman learned that Howard Post was gone and Paramount Cartoons put Shamus Culhane in charge. Culhane hired Beckerman and they creayed a few theatrical films to finish out the Noveltoons series.

One Noveltoon, second to last in the series, was conceived and animated by Howard Beckerman. He also co-designed it with children’s book illustrator Gil Miret. The Trip is about a dude working at a big city office who gets stranded on a desert isle.

It is a study in the fundamentals of animation production. Simple. As elegant as a Hubley Studios film, yet basic enough to embrace slap-stick humor. There is no dialogue or sound-effects, just Winston Sharples’ music, and Shamus Culhane directing. Heigh Ho! It’s off to work they go! Suddenly Culhane stormed off in a huff. Two weeks after Ralph Bakshi took over Beckerman was laid-off.

He rebounded with a job as head of animation at the newly formed D’Amylar Productions. Alymar denotes a very spiritual person who often relies on intuition for decision making. As one of the trendy new service studio, this shop catered to high-end clients, with an office at 440 Park Avenue South and the studio at 155 East 38th Street. Ernest di Giovanni, a former English teacher and sales rep for Stars and Stripes Productions Forever, owned D’Alymar. Vinnie Bell worked there a while. After a year Howard went back to freelancing.

He rebounded with a job as head of animation at the newly formed D’Amylar Productions. Alymar denotes a very spiritual person who often relies on intuition for decision making. As one of the trendy new service studio, this shop catered to high-end clients, with an office at 440 Park Avenue South and the studio at 155 East 38th Street. Ernest di Giovanni, a former English teacher and sales rep for Stars and Stripes Productions Forever, owned D’Alymar. Vinnie Bell worked there a while. After a year Howard went back to freelancing.

Animation found itself in the midst of an identity crisis. Theatrical shorts were fading fast. Television shows were routine drivel, Artistically, TV commercials were pretty much the only path, but were they tarnishing the art-form’s integrity? To prevent that, an international society called ASIFA formed in France to spread appreciation of animation. Chapters were opened around the world. In New York it was ASIFA East. Howard Beckerman participated in its organization alongside Faith and John Hubley, Tissa David, Vince Cafarelli, Dick Rauh, Hal Silvermintz, and others.

Howard volunteered at the Screen Cartoonists Guild, and at ASIFA as he returned to freelancing – for Elektra – for Ray Favata at Gryphon Productions – and for Shamus Culhane on ROCKET ROBIN HOOD.

Howard volunteered at the Screen Cartoonists Guild, and at ASIFA as he returned to freelancing – for Elektra – for Ray Favata at Gryphon Productions – and for Shamus Culhane on ROCKET ROBIN HOOD.

His friend Al Kouzel hired Howard Beckerman in 1969 to write some episodes of WINKY DINK AND YOU. Izzy Klein wrote others. Each episode containes a gimmick where kids used a crayon on a sort of clear vinyl sheet clinging to the TV screen. Violet Gellman managed production. The staff were mostly newer artists, with old-hands Tom Golden and Chuck Harriton mixed in to show them the ropes.

Winky Dink and You!

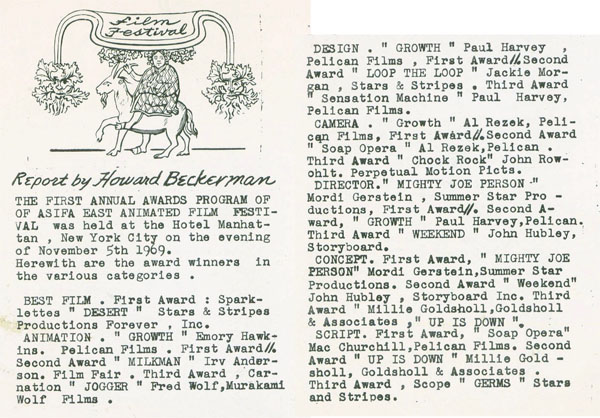

WINKY DINK AND YOU got made at Ariel Productions, 210 Fifth Avenue, across the street from Madison Square Park. If one glanced diagonally across the park they’d see the Neptune Building, where John Bray Studios existed decades earlier. In autumn 1969 ASIFA East held its first Animated Film Festival. Howard Beckerman wrote a report for Top Cel about the exent that December.

Howard ran for the post of Top Cel editor in 1970. It went to Izzy Klein. Howard’s days with the union were nearing an end, anyways. His friend Tee Collins opened his own studio at 2 West 45th Street. It was the first Black-owned animation shop in Manhattan. Tee and Howard had become close when Tee did layouts at UPA. Now, Tee was of the opinion that any real money was being made by studio owners, so why not work for yourself? Tee convinced Howard to do the same.

With more than twenty years of animating under his belt Howard took a plunge. A third daughter, Amy, had been added. The Beckermans opened Howard Beckerman Animation down in the Village at 117 East 18th Street, a block or so from Union Square Park, and a few blocks from Gramercy Park. Iris would put her illustrative skills to use as a designer, inker and painter.

With more than twenty years of animating under his belt Howard took a plunge. A third daughter, Amy, had been added. The Beckermans opened Howard Beckerman Animation down in the Village at 117 East 18th Street, a block or so from Union Square Park, and a few blocks from Gramercy Park. Iris would put her illustrative skills to use as a designer, inker and painter.

They moved in on July 4th. The girls helped lug supplies and were rewarded with ice cream from a neighborhood shop. Suddenly Howard was Management. No live-action stuff, only hand-drawn animation. Corporate-sponsored films and educational stuff were the main fare. He made HOW TO REPRESENT 3D SHAPES for the Xeroz Corporation. At some point he worked for Elinor Bunin, who had PBS contracts, so that might account for some SESAME STREET segments. Howard said this about operating the studio:

“Depending on the size of the job we were doing, I hired other artists and sometimes my students and my daughters. My clients included NBC, CBS, Children’s Television Workshop, Xerox Corporation, American Home Products (Black Flag, etc).”

In 1971 Beckerman lectured at the Westchester Educational Council of Audio-Visual Communications and started teaching at Phoenix School of Design on 49th Street and Lexington Avenue. In 1972 Howard started a course in Animation Drawing, as the School of Visual Arts expanded animation programming.

Howard Beckerman Animation, intermingled with Howard Beckerman Associates, moved to 24 West 45th Street in 1973. A three-story building next to the Harvard Club. Famous Studios used to be directly across the street.

Howard helped create a ‘History of Animation’ class at the School of Visual Arts. That June he supplied the Top Cel cover.

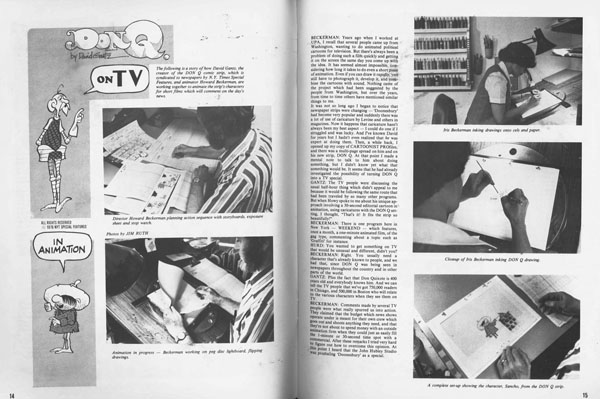

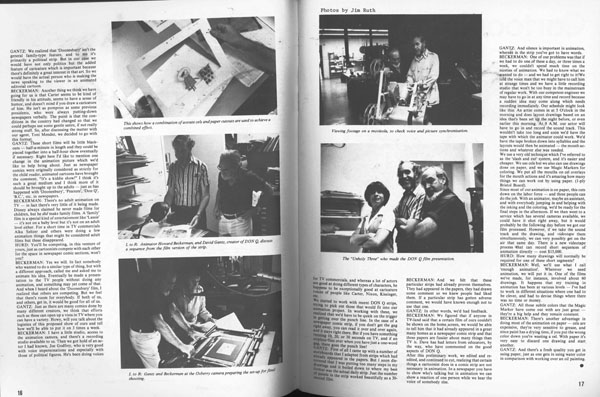

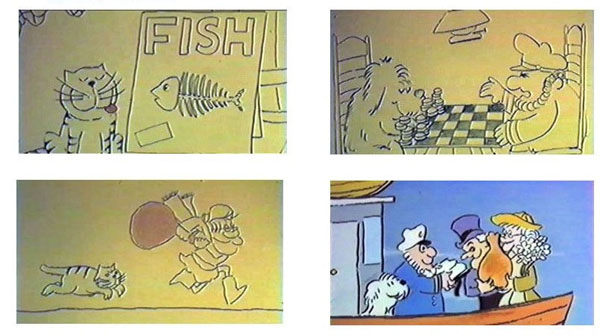

Two years later Howard Beckerman Animation moved to 19 West 45th Street. Folks from Famous Studios had used this building as a shortcut to the subway, due to another entrance on 44th Street. Richard Williams and Shamus Culhane both had studios there at some point. RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY: A MUSICAL ADVENTURE was in full production there during 1976, as Howard and Iris worked at bringing the DON Q comic-strip to television. CARTOONIST PROfiles published this article:

Howard contributed scholarly articles to CARTOONIST PROfiles, MILLIMETER, and other animation based publication. Iris sat on the executive board of ASIFA East, which sometimes sent the couple around the globe representing the organization and prepping international film festivals. He was on his way to being designated ‘the Dean of New York City Animation’.

The Beckermans had a good life. Their daughter Mara was a painter at Perpetual Motion Pictures in 1979. Next year Beckerman’s studio moved across the street to 45 West 45th Street. Joe Oriolo had the Beckermans doing a FELIX THE CAT project with Bill Lorenzo. In 1982 Howard began writing the ANIMATION SPOT column for BACK STAGE Magazine.

Commercial animation was undergoing big changes. Many clients wanted computer generated imagery. Stop-motion animator John Gati had been with Film Frames in the Seventies, then Action Productions until 1981, where he worked on commercials for Long John Silvers Restaurants, and the People’s National Bank & Trust Company in Michigan, as well as a television pilot titled FLUTEY AND THE KNIGHTS during 1981. In 1982 Gati had his own shop. He put out a film for the festival circuit and it played well. John Gati convinced Howard and Iris they should do the same.

Commercial animation was undergoing big changes. Many clients wanted computer generated imagery. Stop-motion animator John Gati had been with Film Frames in the Seventies, then Action Productions until 1981, where he worked on commercials for Long John Silvers Restaurants, and the People’s National Bank & Trust Company in Michigan, as well as a television pilot titled FLUTEY AND THE KNIGHTS during 1981. In 1982 Gati had his own shop. He put out a film for the festival circuit and it played well. John Gati convinced Howard and Iris they should do the same.

Howard conceived a cartoon about a lighthouse beam revealing the night-time antics occurring in a seaside town. BOOP BEEP went on the film festival circuit in 1984.

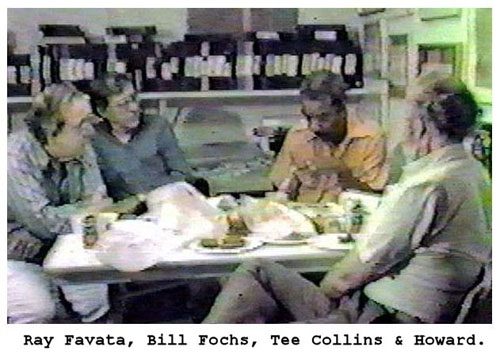

At one point Howard invited Tee Collins, Ray Favata, and Bill Fochs over to sit in front of a video-camera discussing the business. Each of them owned a studio. Bill Fochs did titles and graphics at 321 West 44th Street. Poor storage has rendered the tape unwatchable, but a salvaged aoundtrack is available. https://archive.org/details/45-meet Tee Collins is the first voice.

Howard Beckerman Animation moved again in 1987, this time to 25 West 45th Street. The old Famous Studios address. They remained there until 1990 when Howard brought the studio to his house in Flushing, Queens. He did storyboards for Jumbo Pictures’ show DOUG. It was only one episode, DOUG BAGS A NEMATOID, but Howard had been teaching long enough that it gave him the opportunity to work with some of his old students.

“Doug Bags A Nematoad”

Teaching and ASIFA business kept Howard and Iris active.

Iris got known as a leading restorer of old animation cels, a growing business among art dealers across the country. She restored a lot of early Disney cels. Sadly, in 1998 Iris was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. As the family adjusted to that, Howard focused on teaching both the history and the art of animation. He called upon old conversations with Shamus Culhane, Grim Natwick, and other pioneers of this up-and-down industry. Every new class was told to look at the person sitting next to them, because “you’ll be working for them some day”. He served as advisor for student films. Howard’s travels on behalf of ASIFA granted him a solid world-view that led to his writing ANIMATION THE WHOLE STORY.

Iris got known as a leading restorer of old animation cels, a growing business among art dealers across the country. She restored a lot of early Disney cels. Sadly, in 1998 Iris was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. As the family adjusted to that, Howard focused on teaching both the history and the art of animation. He called upon old conversations with Shamus Culhane, Grim Natwick, and other pioneers of this up-and-down industry. Every new class was told to look at the person sitting next to them, because “you’ll be working for them some day”. He served as advisor for student films. Howard’s travels on behalf of ASIFA granted him a solid world-view that led to his writing ANIMATION THE WHOLE STORY.

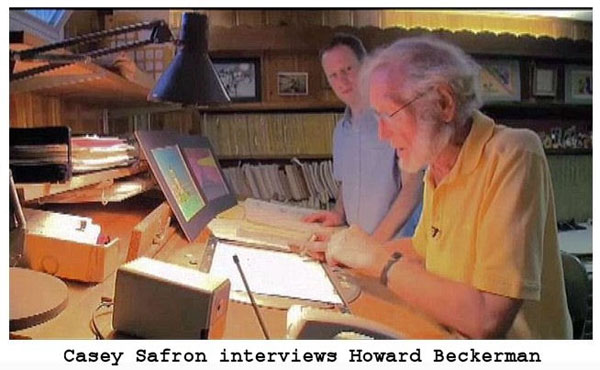

2008 brought FORGING THE FRAME: THE ROOTS OF ANIMATION, 1921-1930, a documentary directed by Greg Ford and Mark Nassief. Howard Beckerman is among the historians interviewed. He did speaking appearances, lectures, or tributes to fellow animators. During 2011 his student Casey Safron produced AT HOME WITH HOWARD BECKERMAN.

Iris Beckerman passed away in April of 2012. Near the end, when Howard would visit Iris in the hospital, he’d see Doris Polansky there. Her husband Marty Polansky was in that same facility. They’d all known each other for years. After both spouses passed, Doris and Howard grieved together, and settled into being companions.

I got to know Howard around 2018. Phil Kimmelman had been remembering who he could put me in contact with . . . so thank you, Phil. And thank you, Howard. Access to your steel-trap memory proved invaluable. Your advice was always sound, and your encouragement often needed. I’m sorry I tried to put a hook in your article. A gentleman such as yourself is above such hokum. You are missed!

Three years ago Howard appeared in CARTOON CARNIVAL, a documentary directed by Andrew T. Smith. Someone, please tell us where we can buy a copy.