What do Walt Disney, Saul Steinberg and Hugo Pratt have in common? Short answer: Mr. Civita.

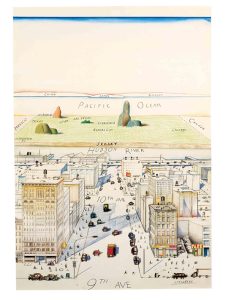

A famous New Yorker cover by Saul Steinberg summarizes the idea in a perspective of New York City streets. Next comes the Atlantic Ocean and then Europe and Asia; it’s easy to imagine a slightly deeper version, with the New York City streets looming again in the skyline. This merry-go-round could also synthesize the life of Cesare Civita, the man who was fundamental for Steinberg to ever arrive in New York City. Or for many other things. Meet Cesare Civita, the original Merry-go-round Man.

A Star is Born

A Star is Born

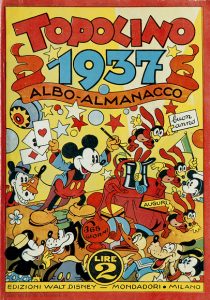

Cesare Civita was born in New York City in 1905. Carlo Civita, his father, was an Italian businessman of Jewish descent, married to the opera singer Vittoria Carpi. His brother Vittorio was also born in New York, while the youngest, Arturo, was born in Milan after the family’s return to Italy in 1909. The Civita brothers spent some periods in the United States, learning business management during the 1920s and early 1930s, to then work with their father in Milan in a importation company and, later, in a garage where they edited for their own clients the monthly publication Garage Moderno e Stazione Servizi, their first publishing experience. After that, Cesare collaborated with various publishing houses until he joined the prestigious Mondadori, where he became co-managing editor, specializing in the magazine section. In Mondadori, Civita secured an exclusive representation agreement for Disney’s publishing production in Italy, which allowed him to launch the magazines Topolino (Mickey Mouse) and Paperino (Donald Duck), together with a small subsidiary label called Edizioni Walt Disney. Civita was also responsible for publications such as Giornale delle Meraviglie, Settebello and Grandi Firme, where he collaborated with Cesare Zavattini, who would later become one of the major figures of Italian neorealism, and with whom he shared a passion for cinema, which led him to make two films during those years, one of them together with the future film director Mario Monicelli, also linked to Mondadori by journalistic and family ties. The feature I ragazzi di via Pal (1935), directed by Civita, Monicelli and Alberto Mondadori, had the particularity of being played by young members of the GUF (Gruppo Universitario Fascista) of Milan.

The title sequence of the movie can be viewed here (in a silent version):

And here it appears the singular aspect of Civita’s coexistence with the political movement that ran Italy (hard to avoid, since Fascism had come to power in 1922). To illustrate the covers of Topolino, he decided not to use the images provided by the American company but to adapt the mouse to local tastes, calling on one of the best-known Italian cartoonists of the period, Antonio Rubino (an artist who deserves a separate chapter). Rubino, who by then had an eclectic and lush career, was, among other things, widely recognized as the main illustrator of Il Balilla, the official organ of the Fascist youth. In any case, his covers for Disney achieve something that is not common among other Disney products elsewhere, keeping Rubino’s style happily cohabiting with Disney’s (perhaps initiating a mark still visible today in the Italian Disney cartoonists, whose production is easily identifiable).

Topolino cover by Rubino.

This situation, bizarre as it seems, may have been a little less so at the time. The Italy of early fascism, despite being ruled by an authoritarian regime, had been perceived as a less dangerous place to live by a large number of refugees coming from countries that were under the orbit of governments ideologically closer to Nazism. One of these visitors, the Romanian Saul Steinberg, an architecture student at the University of Milan and a cartoonist contributor to Settebello (and the similar Bertoldo), was to develop a friendship with Civita on those years that would prove providential.

Men on the Run

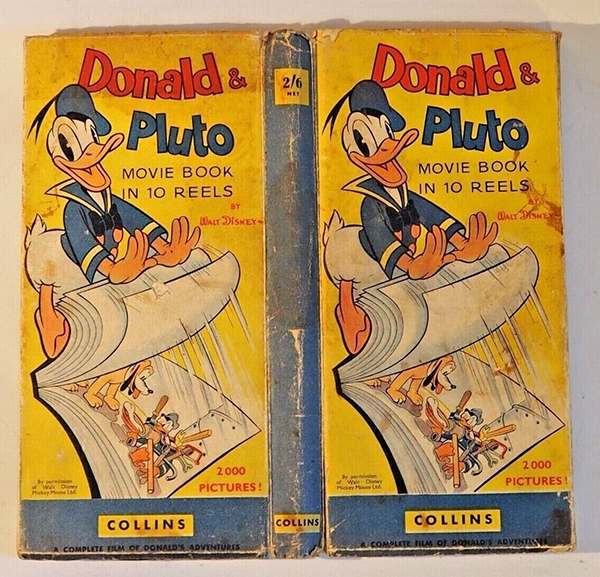

The political mirage came to an end with the promulgation of the racial laws of July 1938 (accompanied by the corresponding “Manifesto sulla purezza della razza”), with which Italy caught up with the latest German fashions. Civita understood that they had to leave the country and organized the departure of his entire family: married in 1929 to Mina Consolo, he had three children; Carlo, Adriana and Barbara. With his elderly parents already settled in New York, Cesare moved to Brussels and then Paris, while his brother Vittorio and his family went to London. As Civita’s money was frozen by the new legislation, Mondadori had given him the rights to the Disney comics as a termination check in order to use it to pay his way out of Europe. He sold to English publishers the old Italian Cinelibri (small flipbooks with Disney characters), while they obtained a visa for the United States. The war had already broken out when he managed to embark at the port of Le Havre on the Washington, the same ship where Thomas Mann was traveling. His family and Vittorio’s had already left Cannes two months earlier, and his third brother, Arturo, had managed to board at Genoa.

Disney’s flipbooks printed by Collins (from Glasgow) in 1939: Civita’s ticket out of Europe.

From his parents’ home in New Rochelle, Cesare tried in vain to rebuild his career as a publisher in the US. This failure made him think of the south of the continent as a market still open and full of opportunities for a publishing house specialized in comics.

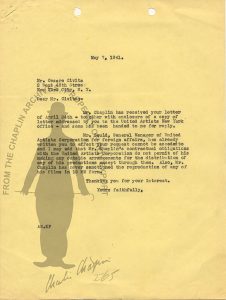

Another venture from Civita in 1941: he tried to buy Chaplin’s The Great Dictator rights in order to exhibit the film in Brazil in 16 mm copies. Chaplin declined.

In 1941, Civita moved permanently to Buenos Aires with his entire family, after having perfected his agreement with Disney, albeit on less favorable terms than expected: he would be a paid employee, with a small share of the profits. By then, his capital had been reduced to his Disney’s deal, his work as an agent and his contacts (which were not few). But there were others who were in a far worse position, and Civita had not forgotten them.

Saul Steinberg in Italy, 1936

Saul Steinberg had been caught in the web of Italy’s racial laws. Although he had been able to complete his studies in Architecture, the new legislation prevented him from any regular work and all his collaborations had to be anonymous.

Cartoon published in Settebello, September 3, 1938. “With this perfect telescope, I see Europe, my city, my house, and through the window myself looking at the world through the telescope while speaking with you; but I don’t hear what I’m saying.” Note the parallel with the later New Yorker cover.

Steinberg received a visa for the Dominican Republic and, from his family and Civita, a ticket on a boat leaving Lisbon for Ciudad Trujillo (now Santo Domingo) via New York, but he was stopped by the Portuguese authorities and sent back to Milan, where the Romanian legation in Rome refused to renew his passport, making him a stateless man subject to arrest. This happened in April 1941 and Steinberg was sent to the internment camp of Tortoreto. There, Steinberg spent his time drawing, painting, writing and receiving letters, and handling the paperwork to obtain new visas for Spain and Portugal. In June, he was released, and this time he was able to pass through Lisbon without any problems in order to board the SS Excalibur headed to New York. As Steinberg had only a transit visa, stayed in Ellis Island. He arrived to República Dominicana in July. From there, Steinberg sent regular packets of drawings to Cesare in New York.

From that moment on, Civita, together with the artist’s family and Vanderbilt Jr., began the slow process of obtaining a US visa for the artist, while getting commercial commissions for him (including the jackpot of The New Yorker). By the time Steinberg was able to travel to the US, Civita was already settled in Argentina.

Note: the information about the relationship between Civita and Steinberg was extracted from the web site of the Saul Steinberg Foundation.

April in Buenos Aires

Editorial Abril early logo.

It was then a matter of raising capital for the fledgling enterprise. Civita miraculously managed to get part of his savings out of Italy through a Roman friar; he obtained loans, pawned a diamond belonging to his wife and to the whole he added his secret weapon: the representation rights of Felix the Cat. Ironically, it was the famous cat who allowed him to escape from the shadow of the mouse, perhaps as a final revenge of the feline that once dominated the screens. Boris Spivacow suggested names for the new publishing house; Editorial Abril was chosen. A little tree (symbol of knowledge) was adopted as logo.

“Pequeños grandes libros”, as they were titled in Argentina, illustrated with Mickey Mouse strips.

For a start, the new publishing house needed a project that would be easy to implement in the short term, compatible with the parallel representation of Disney products. The world war meant a shortage of paper, and Civita saw the advantage of small-sized products, made from the cuttings of the large sheets of paper used by newspapers. He turned his eyes to Better Little Books, from which he acquired the rights of representation.

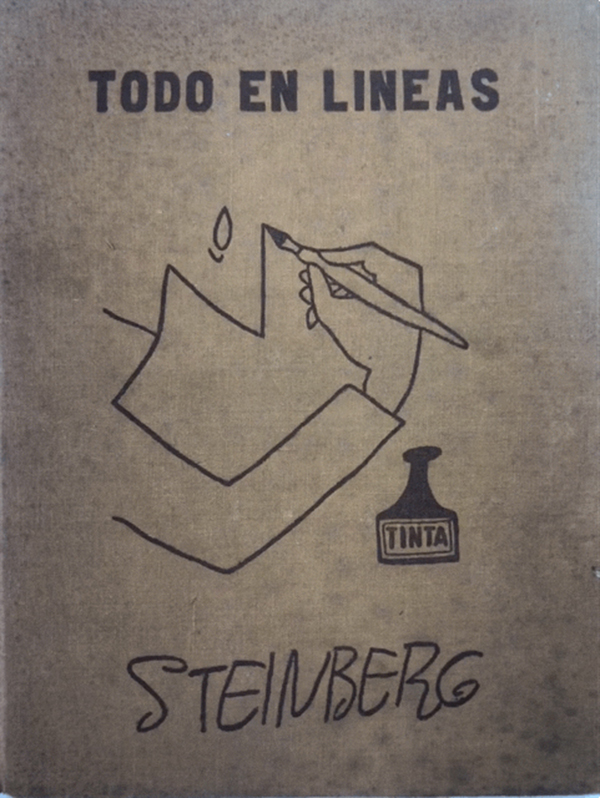

In parallel with his commercial projects, Civita did not fail to try more personal ones, such as the publication of Todo en Línea (“All in line”), the first book by Saul Steinberg, published in 1945, the same year of its US edition. It should also be noted that by then Steinberg’s work was already known in Argentina through Bertoldo, plus the Argentine magazine Cascabel, and the Romanian’s work had already influenced a new generation of local humorists such as Oski (Oscar Conti) and Landrú (Juan Carlos Colombres).

Cover of the argentine edition of “Todo en Línea”

The Maltese Duck

After a few years of career, Editorial Abril became a solid enough company to undertake the publication of a title entirely dedicated to the Disney universe (whose demands were difficult to meet). In 1944, the first issue of El Pato Donald was launched.

Argentine comic magazines from the late forties: Dante Quinerno’s Patrouzito vs. Disney’s Pato Donald.

Civita continued in this publication with his tactic of adapting the character to local tastes, including local episodes of the duck drawn by Luis Destuet (a participant in Quinterno’s Upa en Apuros short, who was in charge of the covers) or allowing Argentine touches in the translations of the comics, largely republishings of Carl Barks’ stories.

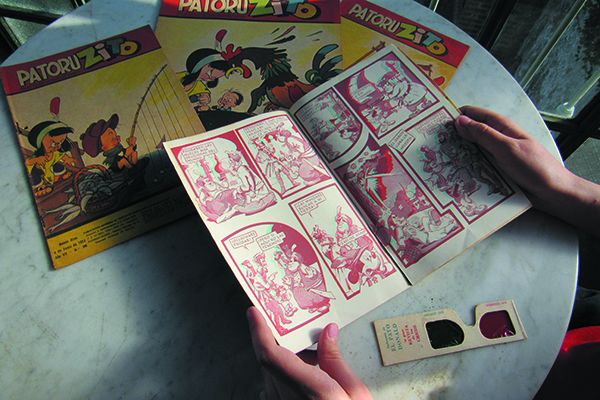

3-D Disney comic, edited by Civita.

The Disney-Civita association continued for many years. Jimmy Johnson, head of Disney’s Publications department, wrote about Civita’s tenure as Disney editor: “In my opinion if there was anyone in the world who might have taken Kay Kamen’s place, it was Cesar.” (Many thanks to Didier Ghez for this quotation of “Inside the Whimsy Works”, Johnson’s biography edited by him and Greg Erhbar).

In the post-war years Civita was able to resume contact with Italy. He quickly noticed how local scriptwriters and cartoonists had become an unemployed workforce, wandering the peninsula and drawing caricatures of soldiers. Argentina, on the other hand, had a large and prosperous public.

“Salgari” magazine

A symbol of the Italian-Argentine confraternity was needed (Italy was by far its first immigration flow in statistical terms) and Civita found it in Emilio Salgari, the great writer of popular novels, author of Sandokan and other classics, avidly read in Argentina. The magazine Salgari (focused on adventure comics) appeared in 1947 and had the particularity of publishing mainly material by Italian authors, such as Walter Molino and Rino Albertarelli. The success of this publication made Civita reformulate the idea, planning the export-import of cartoonists as livestock, instead of doing it only with his production. But some isolated experiences with artists who came and went (such as Sergio Tarquinio) convinced him that the experiment was only feasible with the new generation. He then contacted the young authors of the so-called “Venice Group” formed around the magazine Asso Di Picche: Paul Campani, Dino Battaglia, Alberto Ongaro, Mario Faustinelli and Hugo Pratt (of later Corto Maltese fame).

“Misterix” magazine

Civita then launched the magazine Misterix, a publication whose central figure was the character of the same name, created by Massimo Garnier and Campani. The stars of the publication would be Cesare’s young Turks: Pratt, Pavone, Faustinelli and Ongaro, brought to Argentina to draw comics.

Hugo Pratt before and after Argentina. Who’s happier?

Quickly, Misterix (and the later Rayo Rojo magazine) became a laboratory, and the work of the Italians connected with a generation of new Argentine authors who also started in April, such as the scriptwriters Héctor Germán Oesterheld and Julio Almada or the cartoonists Francisco Solano López and Eugenio Zoppi, among others.

“Gatito” drawn by Hugo Csesc (1953)

At the same time, Civita was planning a series of children’s publications. Through Boris Spivacow, he launched the magazine GATITO. The adventures of the publication’s star –a little white cat living on a fabulous land- were in charge of H. G. Oesterheld, with Hugo Csecs in the drawings. The success of the character was such that he even had a radio version.

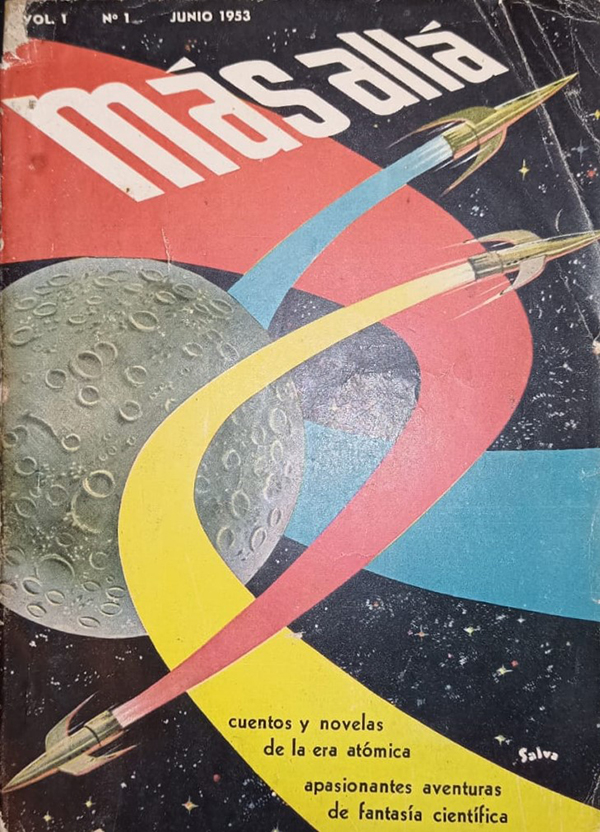

“Más Allá” cover (1953). This particular issue presented some of the first translated stories of Philip K. Dick.

It is not the only new field in which Civita ventured: the magazine Más Allá (“Beyond”), the first one dedicated to Science Fiction in Latin America, had -according to some versions- H.G. Oesterheld as director.

Héctor Germán Oesterheld

Oesterheld-Pratt’s “Sgt. Kirk”, the only important creation from the duo published by Abril.

Paradoxically, the jewels of the Oesterheld-Pratt collaboration (or Solano López’ and Breccia’s) were not published by Editorial Abril but by Editorial Frontera, the venture in which the scriptwriter embarked right after his Abril experience, in search of a greater freedom than the Italian publisher allowed. A similar case was that of Spivacow (after leaving Abril, he organized the university publishing house Eudeba, which revolutionized the Argentine industry, and later the mythical label Centro Editor de América Latina). These experiences consign a fact: Civita’s protégées advanced on grounds where the old Cesare would never have dared (or even been interested), but after learning the ropes under his wing.

Oscar Zarate: a testimony.

Argentine cartoonist Oscar Zárate lives in London. At the age of 82, he has just published there his incredible book “Thomas Girtin: The Forgotten Painter”. He remembers vividly his beginnings in Editorial Abril, in the 50’s. By then, Civita had organized a Syndicate to sell his comics to other countries, called Surameris. Zárate was at that time a young man in charge of adapting pages to other formats or doctoring translations to languages like Italian or Portuguese, since Vittorio, Cesare’s brother, had recently started the Brazilian subsidiary of Editorial Abril.

Oscar Zarate working in Surameris, Civita’s comic syndicate.

Oscar Zárate: When I worked in the Alem street building in the beginning, I cleaned Civita’s office. Next to the desk, on the wall, there was a very large drawing. According to my aesthetics at that time, which was Hugo Pratt’s, it was a drawing made by a child. It was signed: Steinberg. It made me uneasy, because this man I admired, Civita, had this drawing. I didn’t know it was published, I didn’t know it was Steinberg. You see… I thought ‘something is going here; it must not be a doodle’. What happened to me at Editorial Abril was a bit like that, on everything. Every meeting I had with people… that’s when I started to establish a relationship with one guy or another, it was for the first time. There were lot of painters, a lot of poets; there was Onofre Lovero, who did theater. There were artists. Editorial Abril was a seedbed. Because at two o’clock in the afternoon everything was over and everyone stayed to do their things, use the phone, that kind of things.

Photo production for Idilio by Grete Stern.

That’s why a quick review of Civita’s merry-go-round should include Disney and Rubino, Italian neorealism, Saul Steinberg, Hugo Pratt, Oesterheld… Boris Spivacow hanging on the tail of Felix the Cat. It’s enough to make anyone dizzy.

Zárate also notes, with some sadness, that by the time he joined the publishing house, Civita was abandoning comics to focus on other types of publications: Cinemisterio (comic adaptations of famous films) had given way to Idilio (including photo novels, one of them starred by Pratt himself, as our interviewee recalls) and then Claudia, Abril women’s magazine.

As time went by, Civita shed its comic magazines (which passed into the hands of Editorial Yago or other publishers) and concentrated on journalistic publications such as Siete Días Ilustrados or Panorama (with a brief return to comics in the 1970s, representing Hanna-Barbera material, but let’s piously overlook this period).

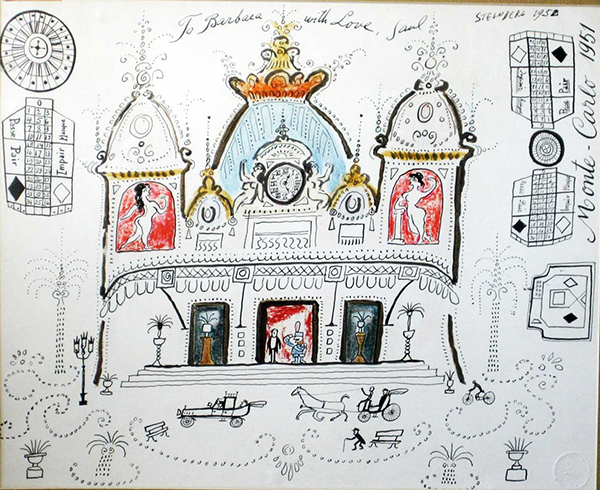

“Monte Carlo”, 1951. A Saul Steinberg drawing dedicated to Barbara Civita.

In any case, Abril’s career as an exclusively journalistic enterprise is another story, one that went all the way to the Argentine last military dictatorship (1976-1983); the same one in which Oesterheld and his four daughters became “desaparecidos”, most of Spivacow production literally went up in smoke, and whose prolegomena convinced Civita that publishing was no longer a safe enterprise… and neither was Argentina (In 1975, a commando attack by helicopter fired on his 18th-story apartment). Civita sold his publications and moved to Brazil and Mexico, only to come back to the country after the return of democracy. Abril’s Brazilian subsidiary, now Grupo Abril, however, is still on operations.

Cesare Civita died in 2005 in Buenos Aires. He could have reached the age of 100, but he surely perceived the idea as a little too round, preferring to stay at 99. Seedbeds are like this, never quite finish what they start. They rather leave some space for the rest.