1947 was a busy year for cartoon circus action, providing enough material to fill this week’s entire entries. Among them, a George Pal Puppetoon, a Disney featurette, a Tex Avery oddity, and visits by Andy Panda, Popeye, and even Inki and the Minah Bird.

Wilbur the Lion (George Pal/Paramount, Puppetoon, 4/18/47 – George Pal, dir.) An enterprising late entry in the Puppetoon series, mostly requiring a large cast of all-new character models. The story opens at a celebration among the performers of a circus. Their star attraction is retiring after 25 years of faithful service. He is Wilbur, a juggling lion, with the ability to talk to other members of the circus cast (in a slowed-down track for Billy Bletcher). Wilbur is awarded a solid gold wristwatch, a first-class steamer trip back to his home, and the blessings and good wishes of the entire cast. The steamer trip is depicted upon a globe map, with the steamer taking an S-curve between the letters reading “Atlantic Ocean”. Wilbur is left on an African beach, waving goodbye as the steamer reverses for its return voyage. The beach seems deserted, but gradually, up from camouflage among the foliage, rise several of Wilbur’s old friends – a giraffe, a rhino, a zebra, and even a small skunk. They are pleased to see Wilbur back after all these years, and ask him where he’s been. “Haven’t you heard?”. replies Wilbur, assuming his reputation should have preceded him. He describes how he was the star of the circus, and tells them to stand back while he gives them a sample of how he “wowed ‘em” in the show. Scat-singing circus music, Wilbur begins juggling Indian clubs over his head. Three of his friends are highly unimpressed, referring among themselves to Wilbur’s performance as “corny tricks”, and commenting that, while Wilbur was once an okay guy, he seems to have gone “high hat” on them. “I’ve seen enough”, they respectively declare, and depart while Wilbur is still in the middle of his act. All that is left to applaud Wilbur at the end of his performance is the timid skunk, who, when he notices the others have left, concludes, “I’d better go, too.”

Wilbur the Lion (George Pal/Paramount, Puppetoon, 4/18/47 – George Pal, dir.) An enterprising late entry in the Puppetoon series, mostly requiring a large cast of all-new character models. The story opens at a celebration among the performers of a circus. Their star attraction is retiring after 25 years of faithful service. He is Wilbur, a juggling lion, with the ability to talk to other members of the circus cast (in a slowed-down track for Billy Bletcher). Wilbur is awarded a solid gold wristwatch, a first-class steamer trip back to his home, and the blessings and good wishes of the entire cast. The steamer trip is depicted upon a globe map, with the steamer taking an S-curve between the letters reading “Atlantic Ocean”. Wilbur is left on an African beach, waving goodbye as the steamer reverses for its return voyage. The beach seems deserted, but gradually, up from camouflage among the foliage, rise several of Wilbur’s old friends – a giraffe, a rhino, a zebra, and even a small skunk. They are pleased to see Wilbur back after all these years, and ask him where he’s been. “Haven’t you heard?”. replies Wilbur, assuming his reputation should have preceded him. He describes how he was the star of the circus, and tells them to stand back while he gives them a sample of how he “wowed ‘em” in the show. Scat-singing circus music, Wilbur begins juggling Indian clubs over his head. Three of his friends are highly unimpressed, referring among themselves to Wilbur’s performance as “corny tricks”, and commenting that, while Wilbur was once an okay guy, he seems to have gone “high hat” on them. “I’ve seen enough”, they respectively declare, and depart while Wilbur is still in the middle of his act. All that is left to applaud Wilbur at the end of his performance is the timid skunk, who, when he notices the others have left, concludes, “I’d better go, too.”

Wilbur is left alone in the jungle, huddling under leaves which supply an ineffective canopy, as an evening rainstorm pours down upon him. An unusual change of mood takes over the film, as Pal recruits the voice talents of Bill Forman, known primarily to West-coast radio fans as “The Whistler”, to provide an omniscient narration which penetrates Wilbur’s mind, including keeping him apprised of what is going on among his true friends back at the circus. The narrator pries into Wilbur’s thoughts, magnifying the split of his feelings between the supposed “joys” of being free versus having lost his jungle friends, being hungry instead of having those nice juicy steaks served up to him in the circus, and having no roof over his head. Meanwhile, back at the circus, times are no more pleasant. A huge void has been left by the absence of Wilbur, and, no matter what act the ringmaster books in replacement of Wilbur’s spot (a jumbo elephant, a laughing hyena), all the crowd will do is chant “We want Wilbur”. After the first performance, the “crowd” dwindles down to less than half the tent, then finally only one old lady, still chanting “I want Wilbur”. The ringmaster is finally forced to hang out a sign, reading “circus for sale”, with no takers.

Wilbur is left alone in the jungle, huddling under leaves which supply an ineffective canopy, as an evening rainstorm pours down upon him. An unusual change of mood takes over the film, as Pal recruits the voice talents of Bill Forman, known primarily to West-coast radio fans as “The Whistler”, to provide an omniscient narration which penetrates Wilbur’s mind, including keeping him apprised of what is going on among his true friends back at the circus. The narrator pries into Wilbur’s thoughts, magnifying the split of his feelings between the supposed “joys” of being free versus having lost his jungle friends, being hungry instead of having those nice juicy steaks served up to him in the circus, and having no roof over his head. Meanwhile, back at the circus, times are no more pleasant. A huge void has been left by the absence of Wilbur, and, no matter what act the ringmaster books in replacement of Wilbur’s spot (a jumbo elephant, a laughing hyena), all the crowd will do is chant “We want Wilbur”. After the first performance, the “crowd” dwindles down to less than half the tent, then finally only one old lady, still chanting “I want Wilbur”. The ringmaster is finally forced to hang out a sign, reading “circus for sale”, with no takers.

The scene returns to the jungle. The narrator still taunts Wilbur’s increasingly negative thoughts of jungle life with reminders, “But you’re free…retired”, driving him nearly to madness with remorse at his decision. Then, a new hazard arises, as shots ring out in the underbrush. A small group of hunters, armed with rifles, are taking pot-shots at him. Wilbur cowers behind a rock, as the narrator informs him that these hunters have been sent by the circus, to capture a lion to take his old spot. (So, are the hunters shooting bullets, or tranquilizer darts? Firing real ammunition would not seem very conducive to the motto, “Bring ‘em back alive.”) As Wilbur begins to crack under the pressure, the narrator suggests a way out – a cage trap has also been set by the hunters nearby, at a safe distance from the rifles. Let the hunters catch you, suggests the narrator, knowing they won’t shoot if Wilbur is already safely inside the cage. Wilbur voluntarily enters the cage, shutting its gate behind him. The scene returns to the circus, where a large poster boasts, “Wilbur is back”, and the crowds again line up in droves for the performance. Wilbur returns to his juggling act to the cheers and applause of the crowd, as the narrator communicates with Wilbur that he’s learned a lesson – the grass isn’t always greener in the other fellow’s yard. Listening intently, Wilbur accidentally allows three Indian clubs to hit himself on the head, and grins sheepishly but happily at the camera, for the fade out.

The scene returns to the jungle. The narrator still taunts Wilbur’s increasingly negative thoughts of jungle life with reminders, “But you’re free…retired”, driving him nearly to madness with remorse at his decision. Then, a new hazard arises, as shots ring out in the underbrush. A small group of hunters, armed with rifles, are taking pot-shots at him. Wilbur cowers behind a rock, as the narrator informs him that these hunters have been sent by the circus, to capture a lion to take his old spot. (So, are the hunters shooting bullets, or tranquilizer darts? Firing real ammunition would not seem very conducive to the motto, “Bring ‘em back alive.”) As Wilbur begins to crack under the pressure, the narrator suggests a way out – a cage trap has also been set by the hunters nearby, at a safe distance from the rifles. Let the hunters catch you, suggests the narrator, knowing they won’t shoot if Wilbur is already safely inside the cage. Wilbur voluntarily enters the cage, shutting its gate behind him. The scene returns to the circus, where a large poster boasts, “Wilbur is back”, and the crowds again line up in droves for the performance. Wilbur returns to his juggling act to the cheers and applause of the crowd, as the narrator communicates with Wilbur that he’s learned a lesson – the grass isn’t always greener in the other fellow’s yard. Listening intently, Wilbur accidentally allows three Indian clubs to hit himself on the head, and grins sheepishly but happily at the camera, for the fade out.

Because we encourage you to see Wilbur The Lion restored in full Technicolor on blu-ray – available on The Puppetoon Movie Vol. 2 – here is a black and white silent home movie version:

Though having very little content on subject for this trail, mention must be made of the Popeye’s Abusement Park (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 4/25/47 – I. Sparber, dir.) – Nominally, Popeye, Olive, and Bluto are at an amusement park, complete with the usual assortment of arcade attractions and thrill rides. Yet for some reason, there just happens to be a circus going on at the same location when the moment calls for it. Popeye and Bluto play the usual round of feats of strength to prove who is the better man. (An upsetting sequence has Popeye engage in an inexplicable act of wanton destruction, just to better Bluto who has just lit up a lighthouse-shaped “Test Your Lung Power” device, then exploded it with the force of his exhale. Popeye telephones a real lighthouse from a pay phone, blows into the phone mouthpiece, and explodes the entire lighthouse long-distance – instantly creating a maritime hazard for all local seafarers! Would Popeye really be that callous about potentially casting brothers in uniform onto the rocks?) Bluto crosses up Popeye with Olive, by knocking Popeye cold, then launching him in a small boat into a Tunnel of Love with a “blonde” – a mermaid mannequin swiped from inside the ride. Olive ditches Popeye for two-timing her, and accompanies Bluto to a souvenir photo parlor, where they pose seated in an old tin Lizzie before a beach backdrop. Bluto suggests they “burn up the camera” by producing a photograph with action – insisting that Olive pitch him a smoldering kiss. When Olive refuses, Bluto threatens that he has ways to deal with dames like her, and steps on the Model T’s gas pedal. Conveniently, someone has negligently left fuel in the tank, and the old heap takes off like a rocket, bound for the tracks of the roller coaster.

Though having very little content on subject for this trail, mention must be made of the Popeye’s Abusement Park (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 4/25/47 – I. Sparber, dir.) – Nominally, Popeye, Olive, and Bluto are at an amusement park, complete with the usual assortment of arcade attractions and thrill rides. Yet for some reason, there just happens to be a circus going on at the same location when the moment calls for it. Popeye and Bluto play the usual round of feats of strength to prove who is the better man. (An upsetting sequence has Popeye engage in an inexplicable act of wanton destruction, just to better Bluto who has just lit up a lighthouse-shaped “Test Your Lung Power” device, then exploded it with the force of his exhale. Popeye telephones a real lighthouse from a pay phone, blows into the phone mouthpiece, and explodes the entire lighthouse long-distance – instantly creating a maritime hazard for all local seafarers! Would Popeye really be that callous about potentially casting brothers in uniform onto the rocks?) Bluto crosses up Popeye with Olive, by knocking Popeye cold, then launching him in a small boat into a Tunnel of Love with a “blonde” – a mermaid mannequin swiped from inside the ride. Olive ditches Popeye for two-timing her, and accompanies Bluto to a souvenir photo parlor, where they pose seated in an old tin Lizzie before a beach backdrop. Bluto suggests they “burn up the camera” by producing a photograph with action – insisting that Olive pitch him a smoldering kiss. When Olive refuses, Bluto threatens that he has ways to deal with dames like her, and steps on the Model T’s gas pedal. Conveniently, someone has negligently left fuel in the tank, and the old heap takes off like a rocket, bound for the tracks of the roller coaster.

As the car careens down the first incline, Bluto again demands romantic attention. “No, no, a thousand times no”, replies Mae Questel, repeating her old line of dialogue from the Max Fleischer/Betty Boop cartoon of the same name. So, despite their being hundreds of feet above ground on the tracks, Bluto tells Olive to “get out and walk.” He throws Olive over the edge, but convenient happenstances continue to save the situation and progress the random plot, as there is for no discernable reason a rope tethered to the inside of the car, in a loop of which Olive’s foot catches, permitting her to be dragged along through the air. In her flight alongside the tracks, Olive first encounters a factory smokestack, knocking it loose and entwining her legs and arms around it. She somehow lets loose from the smokestack, but gets towed through the entrance and exit of a circus tent, picking up three elephants from the act within, all clinging to Olive in trunk-to-tail formation. Popeye reappears, scaling the roller coaster on skis, with plungers for ski poles, and ski-jumps off one of the coaster’s slopes, dropping in on Bluto. The two sailors abandon the car to engage in battle on the tracks. A surprise added player shows up behind them, in the form of an actual steam locomotive, just deciding to run on the same track. Popeye saves Bluto’s life, dropping the two of them between cross-ties of the trestle to avoid the train – but Bluto has just enough gratitude to say “Thanks”, then resumes trying to murder the pop-eyed sailor. Popeye almost loses his spinach can below the tracks, but gets his dose, socking Bluto back to the runaway car. Bluto rips out the gas tank from the now-battered vehicle, attempting to bash Popeye with it, but Popeye slams the tank onto Bluto’s head, then ignites the fuel within with his pipe. Bluto is rocketed into space, where the tank explodes in a fireworks display. The car, Popeye, Olive, and the elephants finally fly off a sharp curve at the end of the coaster, soaring through the air, and crashing through the wall of the photography studio. The story ends with Olive finally getting her picture taken, in a “romantic pose” with Popeye, who balances on one hand the three elephants as a replica of Dumbo’s “pyramid of pachyderms”, complete with a battered Bluto atop the pinnacle of the pyramid.

As the car careens down the first incline, Bluto again demands romantic attention. “No, no, a thousand times no”, replies Mae Questel, repeating her old line of dialogue from the Max Fleischer/Betty Boop cartoon of the same name. So, despite their being hundreds of feet above ground on the tracks, Bluto tells Olive to “get out and walk.” He throws Olive over the edge, but convenient happenstances continue to save the situation and progress the random plot, as there is for no discernable reason a rope tethered to the inside of the car, in a loop of which Olive’s foot catches, permitting her to be dragged along through the air. In her flight alongside the tracks, Olive first encounters a factory smokestack, knocking it loose and entwining her legs and arms around it. She somehow lets loose from the smokestack, but gets towed through the entrance and exit of a circus tent, picking up three elephants from the act within, all clinging to Olive in trunk-to-tail formation. Popeye reappears, scaling the roller coaster on skis, with plungers for ski poles, and ski-jumps off one of the coaster’s slopes, dropping in on Bluto. The two sailors abandon the car to engage in battle on the tracks. A surprise added player shows up behind them, in the form of an actual steam locomotive, just deciding to run on the same track. Popeye saves Bluto’s life, dropping the two of them between cross-ties of the trestle to avoid the train – but Bluto has just enough gratitude to say “Thanks”, then resumes trying to murder the pop-eyed sailor. Popeye almost loses his spinach can below the tracks, but gets his dose, socking Bluto back to the runaway car. Bluto rips out the gas tank from the now-battered vehicle, attempting to bash Popeye with it, but Popeye slams the tank onto Bluto’s head, then ignites the fuel within with his pipe. Bluto is rocketed into space, where the tank explodes in a fireworks display. The car, Popeye, Olive, and the elephants finally fly off a sharp curve at the end of the coaster, soaring through the air, and crashing through the wall of the photography studio. The story ends with Olive finally getting her picture taken, in a “romantic pose” with Popeye, who balances on one hand the three elephants as a replica of Dumbo’s “pyramid of pachyderms”, complete with a battered Bluto atop the pinnacle of the pyramid.

It looks like I’ll have to go from memory on Hobo Bobo (Warner, 5/17/47 – Robert McKimson, dir.), which seems to be one of the only Warner shorts not to hit the internet (but it’s now out and newly restored on Looney Tunes Collectors Choice Vol. 3. End of plug). Bobo, a baby elephant, lives in India, where he is required by his owners to carry small logs. He realizes, however, that the older elephants around him carry bigger and bigger logs, and thus foresees a “dark” future for himself (in a crystal ball that turns into an 8 ball). However, he receives a photograph in the mail from his uncle in New York, who is performing with a circus, showing him playing on a circus baseball team. Bobo decodes that is the life for him, escapes his owners, and attempts to board a ship bound for New York. He is immediately thrown off, the ship refusing to take on an elephant. In his only cameo appearance outside of the “Inki” series (an entry of which is discussed in detail below), the Minah Bird shows up, to give Bobo some advice in pantomime on how to get aboard ship undetected. Simply paint yourself pink. Bobo has no idea why this should work, but the savvy bird knows that no one will admit to seeing a pink elephant. Bobo thus climbs the gangplank, right past the purser’s nose, without opposition, as he and others remove bottles from their pockets and smash them.

It looks like I’ll have to go from memory on Hobo Bobo (Warner, 5/17/47 – Robert McKimson, dir.), which seems to be one of the only Warner shorts not to hit the internet (but it’s now out and newly restored on Looney Tunes Collectors Choice Vol. 3. End of plug). Bobo, a baby elephant, lives in India, where he is required by his owners to carry small logs. He realizes, however, that the older elephants around him carry bigger and bigger logs, and thus foresees a “dark” future for himself (in a crystal ball that turns into an 8 ball). However, he receives a photograph in the mail from his uncle in New York, who is performing with a circus, showing him playing on a circus baseball team. Bobo decodes that is the life for him, escapes his owners, and attempts to board a ship bound for New York. He is immediately thrown off, the ship refusing to take on an elephant. In his only cameo appearance outside of the “Inki” series (an entry of which is discussed in detail below), the Minah Bird shows up, to give Bobo some advice in pantomime on how to get aboard ship undetected. Simply paint yourself pink. Bobo has no idea why this should work, but the savvy bird knows that no one will admit to seeing a pink elephant. Bobo thus climbs the gangplank, right past the purser’s nose, without opposition, as he and others remove bottles from their pockets and smash them.

Bobo obtains the run of the ship, able to roam the decks right past the tourists, although he is a bit upset that no one will be friends with him. He even meets the captain, and “takes a turn at the wheel” with his trunk on the bridge, while the captain, careful not to let others see, tries to pull the wheel back under his command by another of its handles. Finally, the ship reaches New York, where Bobo is again upset that his trunk is the only one which will not be inspected by the customs agents. Bobo becomes lost and isolated in the big city, as no one, not even traffic cops, will give him directions to the circus, all continuing to treat him as invisible. He suts down upon a sidewalk curb to bemoan his poor luck, when a water wagon passes to clean the streets. Bobo is splashed with water, which washes off his coat of pink. Oh, the humiliation, thinks Bobo. But suddenly, he is the center of attention. A grey elephant, loose in the big city. Police are called in, and Bobo is handcuffed and placed under arrest (another devastating humiliation). He is brought before a judge, and hears whispers of talk of something called “the chair”. The judge pronounces sentence ipon him of “life” – in the circus. The narrator sums up Bobo’s reaction with the phrase “Why, that’s the answer to the $64 question” (reference to a radio quiz show of the same name). Bobo makes good, not only becoming part of the circus, but even a member of its baseball team. He is now the official bat boy. In his only line of dialogue in the film, Bobo delivers the curtain line to the audience a la Lou Costello: “Bat boy, schmat boy! I’m still carrying logs!”

Bobo obtains the run of the ship, able to roam the decks right past the tourists, although he is a bit upset that no one will be friends with him. He even meets the captain, and “takes a turn at the wheel” with his trunk on the bridge, while the captain, careful not to let others see, tries to pull the wheel back under his command by another of its handles. Finally, the ship reaches New York, where Bobo is again upset that his trunk is the only one which will not be inspected by the customs agents. Bobo becomes lost and isolated in the big city, as no one, not even traffic cops, will give him directions to the circus, all continuing to treat him as invisible. He suts down upon a sidewalk curb to bemoan his poor luck, when a water wagon passes to clean the streets. Bobo is splashed with water, which washes off his coat of pink. Oh, the humiliation, thinks Bobo. But suddenly, he is the center of attention. A grey elephant, loose in the big city. Police are called in, and Bobo is handcuffed and placed under arrest (another devastating humiliation). He is brought before a judge, and hears whispers of talk of something called “the chair”. The judge pronounces sentence ipon him of “life” – in the circus. The narrator sums up Bobo’s reaction with the phrase “Why, that’s the answer to the $64 question” (reference to a radio quiz show of the same name). Bobo makes good, not only becoming part of the circus, but even a member of its baseball team. He is now the official bat boy. In his only line of dialogue in the film, Bobo delivers the curtain line to the audience a la Lou Costello: “Bat boy, schmat boy! I’m still carrying logs!”

Inki at the Circus (Warner, Inki and the Minah Bird, 6/21/47 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.) – First, to clear up a matter of confusion, although the name of the bird species is generally referred to today with a spelling of “mynah”, Chuck Jones’ earlier title in this recurring series uses the spelling “minah”. Whether this is possibly a typo in the Blue Ribbon reissue of the earlier film (of which there were a few in other instances), or whether Jones treated this as a special character name unique to his own bird, remains unknown. In respect for Chuck’s wishes, I will herein utilize the spelling “minah”.

While most episodes of this series tend to feel the same, always involving jungles, lions, and the ever-present slow-pacing mystery bird with super-resilience and strength, this one is an unusual standout, breaking many of the series’ rules. Although we have a circus as a setting, there is no lion. The primary contenders are mild-mannered Inki, for once spearless, captured, and cast by the circus into the unlikely billing of an African Wildman (although the wildest thing he can do is play with a yo-yo), and two stray dogs. Inki also has a change of “wardrobe” from the usual – returning to a design Jones had utilized for a small native in “Porky’s Ant” – a large bone tied into his hair. Much as in “Ant”, the bone plays the central role as the object of desire – and battle – between the two dogs, with poor Inki along for the ride as he merely tries to preserve his coiffeur. The troubles begin when a knothole in the cage wall where Inki is being displayed is popped out of place by a protruding sniffing nose poking in from outside the cage. The nose is removed from the hole and quickly replaced by a curious eye – followed by a view below of a tongue through a crack between wall boards, smacking its “lips” in hungry anticipation of a feast within. The dog who owns all three aforementioned body parts enters the cage, sidling up to the puzzled Inki, and giving him a lick on the cheek, more in the manner of the way he wishes he could lick the bone. The dog tries to take a chomp on the bone, but Inki turns his head, placing the bone out of reach, and eyes the dog questioningly. The dog bluffs, pretending he is only nipping at fleas on his person. Then, the dog goes into the pose of a pointer. When Inki looks to see what the canine is pointing at, the dog zips around behind him, clamps onto the bone, and begins carrying Inki bodily by the hair out onto the circus grounds. With a few quick scrapes by his front feet, the dog digs a hole in the ground, and Inki is dropped upside down into the hole, where the dog buries the bone completely, but leaves the rest of Inki sticking out and helpless to escape.

While most episodes of this series tend to feel the same, always involving jungles, lions, and the ever-present slow-pacing mystery bird with super-resilience and strength, this one is an unusual standout, breaking many of the series’ rules. Although we have a circus as a setting, there is no lion. The primary contenders are mild-mannered Inki, for once spearless, captured, and cast by the circus into the unlikely billing of an African Wildman (although the wildest thing he can do is play with a yo-yo), and two stray dogs. Inki also has a change of “wardrobe” from the usual – returning to a design Jones had utilized for a small native in “Porky’s Ant” – a large bone tied into his hair. Much as in “Ant”, the bone plays the central role as the object of desire – and battle – between the two dogs, with poor Inki along for the ride as he merely tries to preserve his coiffeur. The troubles begin when a knothole in the cage wall where Inki is being displayed is popped out of place by a protruding sniffing nose poking in from outside the cage. The nose is removed from the hole and quickly replaced by a curious eye – followed by a view below of a tongue through a crack between wall boards, smacking its “lips” in hungry anticipation of a feast within. The dog who owns all three aforementioned body parts enters the cage, sidling up to the puzzled Inki, and giving him a lick on the cheek, more in the manner of the way he wishes he could lick the bone. The dog tries to take a chomp on the bone, but Inki turns his head, placing the bone out of reach, and eyes the dog questioningly. The dog bluffs, pretending he is only nipping at fleas on his person. Then, the dog goes into the pose of a pointer. When Inki looks to see what the canine is pointing at, the dog zips around behind him, clamps onto the bone, and begins carrying Inki bodily by the hair out onto the circus grounds. With a few quick scrapes by his front feet, the dog digs a hole in the ground, and Inki is dropped upside down into the hole, where the dog buries the bone completely, but leaves the rest of Inki sticking out and helpless to escape.

The dog saunters away from the buried bone with a feeling of pride in ownership – until he passes another stray dog who has wandered onto the grounds, going in the opposite direction. After a few steps, the first dog stops, just wondering what the second dog is up to. With suspicion in his mind, dog 1 returns to the site of the hole, only to find bare earth opened up again, and no sign of Inki or the precious bone. Dog 1 zips out of frame to pursue the thief. Remembering a preceding wartime dog epic of Frank Tashlin involving competition for rationed meat (“Behind the Meat-Ball”), Jones lifts an entire sequence from the earlier film, as each dog passes before a fence, only to get clobbered by the other as they reach the fence’s end. The bone changes hands – that is, jaws – three times. Then, a close shot reveals the two dogs walking together side by side, each one with its jaws locked on respective ends of the same bone. Suddenly, there is a rumbling from a huge crate, containing a steel vault within. The vault door is broken forcefully open from inside, and out pops – you guessed it – the mystery minah bird, in his usual “Fingal’s Cave” theme slow walk. The dogs are temporarily frightened to opposite sides of the Midway, dropping Inki. Seeing only the small bird, they follow to investigate, as the bird disappears down a hole in the ground left by a tent pole. The dogs poke their sniffers into the hole simultaneously, only to emerge a moment later, with their noses tied in a knot by the resourceful bird. In another moment, the minah reappears out of a bucket close to Inki. Inki extends a hand in friendship to the bird for placing his enemies at bay. But, as is typical for the series, the minah makes no friends nor alliances. The bird extends his wing tip toward Inki’s bone, giving the end of the bone a snap of his fingers (feathers). This sets the bone into a spin like a helicopter blade, then Inki himself spins as his hair unwinds from the coil.

The dog saunters away from the buried bone with a feeling of pride in ownership – until he passes another stray dog who has wandered onto the grounds, going in the opposite direction. After a few steps, the first dog stops, just wondering what the second dog is up to. With suspicion in his mind, dog 1 returns to the site of the hole, only to find bare earth opened up again, and no sign of Inki or the precious bone. Dog 1 zips out of frame to pursue the thief. Remembering a preceding wartime dog epic of Frank Tashlin involving competition for rationed meat (“Behind the Meat-Ball”), Jones lifts an entire sequence from the earlier film, as each dog passes before a fence, only to get clobbered by the other as they reach the fence’s end. The bone changes hands – that is, jaws – three times. Then, a close shot reveals the two dogs walking together side by side, each one with its jaws locked on respective ends of the same bone. Suddenly, there is a rumbling from a huge crate, containing a steel vault within. The vault door is broken forcefully open from inside, and out pops – you guessed it – the mystery minah bird, in his usual “Fingal’s Cave” theme slow walk. The dogs are temporarily frightened to opposite sides of the Midway, dropping Inki. Seeing only the small bird, they follow to investigate, as the bird disappears down a hole in the ground left by a tent pole. The dogs poke their sniffers into the hole simultaneously, only to emerge a moment later, with their noses tied in a knot by the resourceful bird. In another moment, the minah reappears out of a bucket close to Inki. Inki extends a hand in friendship to the bird for placing his enemies at bay. But, as is typical for the series, the minah makes no friends nor alliances. The bird extends his wing tip toward Inki’s bone, giving the end of the bone a snap of his fingers (feathers). This sets the bone into a spin like a helicopter blade, then Inki himself spins as his hair unwinds from the coil.

Inki and dog 1 engage in a funny game of matching pantomime, as the dog turns up on the opposite side of a tent canvas from Inki, and smells the bone close by. Both disappear under the canvas to investigate, always coming out on the opposite side at the same time so that their companion remains unseen by them. Then each darts under the canvas halfway, leaving their rear ends exposed to view of the other. To rid themselves of their adversary, both characters place lighted firecrackers under each other’s rears. But both remain safe as they respectively tiptoe away from the firecrackers on opposite sides of the canvas to await the explosion. They meet at the end of the canvas wall, plugging their ears to await the firecracker blast, then nod to each other in satisfaction at a job well done – until realization strikes that their adversary is still there, face-to-face with them. Inki retreats up a staircase and into a high entrance to the main tent, as dog 1 follows closely behind. After running a good distance inside the tent, they look around to get their bearings, and discover they are perched upon the high wire, hundreds of feet above the center ring. Fearing for their lives, the two begin to move cautiously and slowly, gently retracing their steps back across the wire to the platform level from which they made theur entrance. Their balance is fine, until something begins jostling the wire in rhythmic vibrations. The familiar musical theme signals us it is the minah bird, who has chosen this crucial moment to walk in nonchalance across the wire from the opposite direction. The dog notices a further unexpected development from the wire vibrations – the knot in the end of the cable supporting them all is unraveling. The dog takes a mighty leap as the wire falls, catching the platform with his front paws, and scrambling out the tent entrance. Inki can’t reach the platform, and falls, bouncing off a tightly-supported safety net below.

Inki and dog 1 engage in a funny game of matching pantomime, as the dog turns up on the opposite side of a tent canvas from Inki, and smells the bone close by. Both disappear under the canvas to investigate, always coming out on the opposite side at the same time so that their companion remains unseen by them. Then each darts under the canvas halfway, leaving their rear ends exposed to view of the other. To rid themselves of their adversary, both characters place lighted firecrackers under each other’s rears. But both remain safe as they respectively tiptoe away from the firecrackers on opposite sides of the canvas to await the explosion. They meet at the end of the canvas wall, plugging their ears to await the firecracker blast, then nod to each other in satisfaction at a job well done – until realization strikes that their adversary is still there, face-to-face with them. Inki retreats up a staircase and into a high entrance to the main tent, as dog 1 follows closely behind. After running a good distance inside the tent, they look around to get their bearings, and discover they are perched upon the high wire, hundreds of feet above the center ring. Fearing for their lives, the two begin to move cautiously and slowly, gently retracing their steps back across the wire to the platform level from which they made theur entrance. Their balance is fine, until something begins jostling the wire in rhythmic vibrations. The familiar musical theme signals us it is the minah bird, who has chosen this crucial moment to walk in nonchalance across the wire from the opposite direction. The dog notices a further unexpected development from the wire vibrations – the knot in the end of the cable supporting them all is unraveling. The dog takes a mighty leap as the wire falls, catching the platform with his front paws, and scrambling out the tent entrance. Inki can’t reach the platform, and falls, bouncing off a tightly-supported safety net below.

Inki continues to bounce up and down off the net several times, his bone rising at crucial intervals to provide a next stepping stone for the minah bird, who never falls, but receives just enough support from Inki to make it to the platform, then disappears out the door. Inki bounces upwards a final time, colliding headfirst with the bottom of the platform. Somehow, the bone pops through a small hole in the platform board, without snapping, suspending Inki from it below. Dog 1 reappears through the doorway, grabbing at the bone – but has great difficulty in taking it, at first unable to yank Inki throigh the hole. One tremendous tug, and Inki pops through, sending the dog and Inki flying off the platform into the upper recesses of the tent. There, they wind up suspended by the dog’s toes from a trapeze, the dog holding onto Inki’s ankles. Re-enter dog 2, who appears on a platform at the opposite side of the tent, taking hold of another trapeze to swing out to join the others. On each swing of Inki and dog 1, dog 2 attempts to chomp at Inki’s bone. Dog 2 finally makes teeth contact with something – but that something turns out to be a 1,000 poumd barbell supplied by the minah bird, riding upon a third trapeze. Dog 2 is yanked down to ground level by the barbell’s weight, the trapeze ropes some extending as if they were bungee cords. Dog 2 releases his bite on the barbell, and receives a slingshot flight through the roof of the tent and back through again, where he collides with dog 1 and Inki, causing them to lose their foothold on the trapeze. All three fall, with the bone finally coming loose from Inki’s hair and taking the lead in a four-way chase. As the bone slides down an inclined ramp, the dogs obtain bicycles and give chase down through a loop-de-loop, while Inki makes the same trip without bicycle, sliding on his rear end. They all land in a bucket, one after the other. The bone changes possession twice, then, when all are in the bucket, seems to have disappeared. But a rumbling in the bucket indicates something’s up – and out pops the minah bird again, wearing the bone in his feathers in the same style as Inki, for the iris out.

Inki continues to bounce up and down off the net several times, his bone rising at crucial intervals to provide a next stepping stone for the minah bird, who never falls, but receives just enough support from Inki to make it to the platform, then disappears out the door. Inki bounces upwards a final time, colliding headfirst with the bottom of the platform. Somehow, the bone pops through a small hole in the platform board, without snapping, suspending Inki from it below. Dog 1 reappears through the doorway, grabbing at the bone – but has great difficulty in taking it, at first unable to yank Inki throigh the hole. One tremendous tug, and Inki pops through, sending the dog and Inki flying off the platform into the upper recesses of the tent. There, they wind up suspended by the dog’s toes from a trapeze, the dog holding onto Inki’s ankles. Re-enter dog 2, who appears on a platform at the opposite side of the tent, taking hold of another trapeze to swing out to join the others. On each swing of Inki and dog 1, dog 2 attempts to chomp at Inki’s bone. Dog 2 finally makes teeth contact with something – but that something turns out to be a 1,000 poumd barbell supplied by the minah bird, riding upon a third trapeze. Dog 2 is yanked down to ground level by the barbell’s weight, the trapeze ropes some extending as if they were bungee cords. Dog 2 releases his bite on the barbell, and receives a slingshot flight through the roof of the tent and back through again, where he collides with dog 1 and Inki, causing them to lose their foothold on the trapeze. All three fall, with the bone finally coming loose from Inki’s hair and taking the lead in a four-way chase. As the bone slides down an inclined ramp, the dogs obtain bicycles and give chase down through a loop-de-loop, while Inki makes the same trip without bicycle, sliding on his rear end. They all land in a bucket, one after the other. The bone changes possession twice, then, when all are in the bucket, seems to have disappeared. But a rumbling in the bucket indicates something’s up – and out pops the minah bird again, wearing the bone in his feathers in the same style as Inki, for the iris out.

Slap Happy Lion (MGM, 9/20/47 – Tex Avery, dir.) – A film which some folks seem to find unsettling (to some degree, muself included as a child), looking for laughs out of the subject matter of facing your greatest fears. In large part, it is structured in two nearly equal portions, each consisting of theme and variation upon one repeated joke. The story’s only direct connection to our present trail comes in its present-day wraparounds, as we are introduced at the grounds of the Jingling Brothers Circus (same name as previously encountered by Willoughby Wren) to a lion in a wheelchair, being wheeled from his cage to a hospital ward. The lion is not just cracking up – he’s already fully cracked, as he chain-smokes (off a row of cigarettes fasted to a munitions belt), guzzles booze, cuts paper dolls, and whacks himself in the head with a mellet. (Hey, Screwy Squirrel? Can you use a roommate?) Never explained is what this lion is doing with the circus in the first place, as the narration of a small mouse from under a circus wagon begins to explain that this crack-up occurred while the lion was still in the jungle as reigning king of beasts. So why would any circus want to capture an obviously lunatic lion? The mouse continues to inform us that the lion is mouse-shocked – scared to death of a rodent (who it appears may not be another mouse spoken of in the third person, but our narrator himself).

Slap Happy Lion (MGM, 9/20/47 – Tex Avery, dir.) – A film which some folks seem to find unsettling (to some degree, muself included as a child), looking for laughs out of the subject matter of facing your greatest fears. In large part, it is structured in two nearly equal portions, each consisting of theme and variation upon one repeated joke. The story’s only direct connection to our present trail comes in its present-day wraparounds, as we are introduced at the grounds of the Jingling Brothers Circus (same name as previously encountered by Willoughby Wren) to a lion in a wheelchair, being wheeled from his cage to a hospital ward. The lion is not just cracking up – he’s already fully cracked, as he chain-smokes (off a row of cigarettes fasted to a munitions belt), guzzles booze, cuts paper dolls, and whacks himself in the head with a mellet. (Hey, Screwy Squirrel? Can you use a roommate?) Never explained is what this lion is doing with the circus in the first place, as the narration of a small mouse from under a circus wagon begins to explain that this crack-up occurred while the lion was still in the jungle as reigning king of beasts. So why would any circus want to capture an obviously lunatic lion? The mouse continues to inform us that the lion is mouse-shocked – scared to death of a rodent (who it appears may not be another mouse spoken of in the third person, but our narrator himself).

A flashback takes us into the heart of the jungle, where at least a third of the picture is spent following the effects of the lion’s mighty roar. Each roar leaves the lion in a different state of contortion, including reduction of body to pencil thinness (a gag Avery no doubt remembered from an early Oswald Rabbit short he worked on, Radio Rhythm (1931), shown there as the result of a walrus holding a bass note too long), false teeth falling out, an extension of neck bones and lower lip to resemble a Ubangi warrior, and the old gag of mane descending to waistline to form a hula skirt. The jungle animals react in a montage of fright gags that could easily have graced any Casper cartoon if the writers had been in a creative mood. A zebra jumps out of his stripes, then the stripes independently panic and follow the zebra. Crocodiles abandon a river, with one having a midget body, and uttering one of Avery’s stand-by punchlines since the Warner days: “Well. I’ve been sick.” A gag is lifted from Friz Freleng’s “The Lyin’ Lion”, with an ostrich burying his head in the sand, then uprooting the land around his head so he can run away while still buried. A kangaroo leaps into the safety of another’s pouch, then that kangaroo makes the same retreat into a third kangaroo’s pouch. When the third kangaroo realizes it has no other kangaroo to hide in, it leaps into its own pouch, spiraling inside to disappear completely. Four snakes grab hold of their own tails with their jaws, then roll away together in the manner of the wheels of an invisible car.

A flashback takes us into the heart of the jungle, where at least a third of the picture is spent following the effects of the lion’s mighty roar. Each roar leaves the lion in a different state of contortion, including reduction of body to pencil thinness (a gag Avery no doubt remembered from an early Oswald Rabbit short he worked on, Radio Rhythm (1931), shown there as the result of a walrus holding a bass note too long), false teeth falling out, an extension of neck bones and lower lip to resemble a Ubangi warrior, and the old gag of mane descending to waistline to form a hula skirt. The jungle animals react in a montage of fright gags that could easily have graced any Casper cartoon if the writers had been in a creative mood. A zebra jumps out of his stripes, then the stripes independently panic and follow the zebra. Crocodiles abandon a river, with one having a midget body, and uttering one of Avery’s stand-by punchlines since the Warner days: “Well. I’ve been sick.” A gag is lifted from Friz Freleng’s “The Lyin’ Lion”, with an ostrich burying his head in the sand, then uprooting the land around his head so he can run away while still buried. A kangaroo leaps into the safety of another’s pouch, then that kangaroo makes the same retreat into a third kangaroo’s pouch. When the third kangaroo realizes it has no other kangaroo to hide in, it leaps into its own pouch, spiraling inside to disappear completely. Four snakes grab hold of their own tails with their jaws, then roll away together in the manner of the wheels of an invisible car.

After a brief return to our narrator, we fast-forward to another flashback, on the day the lion first met a mouse. The overconfident rodent, without a sign of fear, must think he can get away with the same tricks applicable to elephants, as he marches up behind the lion, grabs his tail for attention, and merely utters the word “Boo”. The lion, with no explanation provided, freaks out, pulling up his fur like the hemlines of a frightened female facing a mouse in the kitchen, and uttering a woman’s screams. The lion retreats up a tree, and the mouse snaps his fingers at the big cat, as if doing this kind of thing is all in his day’s work. The lion stops to think about it, and takes offense at the little pipsqueak showing him up. Building up his courage, the lion tugs the mouse’s tail for attention, then lets fly with a roar so powerful, it rotates his body like the cylinder of a retracting windowshade. But the lion’s fierce expression literally melts away before our eyes, as the mouse, not phased at all by the lion’s show, begins to march directly at the lion’s face. The perspiring lion withdraws backwards, until the mouse has walked up upon his torso, then all the way to his head, and takes the opportunity to lift open one of the lion’s eyelids, and spit straight into his eye. The lion tries again to get the upper hand of the situation, lying in wait in the mouse’s path with jaws wide open, and tongue unrolled upon the ground like a red carpet to the entrance. The mouse avoids being chewed by standing in a vacant spot of the lion’s gums where a tooth is missing, but is eventually swallowed into the lion’s stomach. There, he grabs two bones left over from a previous meal, and starts playing a musical xylophone solo upon the lion’s internal rib cage. To put a stop to this painful melody, the lion swallows a lit bomb. The mouse swiftly exits back through the lion’s throat, the lion unrolling his tongue to provide the mouse with a staircase for a quick departure. But the lion has forgotten all about the bomb, which emits trails of smoke out of his mouth. For about 20 seconds, the lion runs a race to nowhere, unable to escape his own person, inside which the shape of the bomb still protrudes through his tail. Finally realizing that running is pointless, the lion sadly waves bye-bye to the camera, as the explosion blasts away all meat and fur, exposing the lion’s waving skeleton. Then, the lion’s fur and head fall from the sky, back into place upon his bones.

After a brief return to our narrator, we fast-forward to another flashback, on the day the lion first met a mouse. The overconfident rodent, without a sign of fear, must think he can get away with the same tricks applicable to elephants, as he marches up behind the lion, grabs his tail for attention, and merely utters the word “Boo”. The lion, with no explanation provided, freaks out, pulling up his fur like the hemlines of a frightened female facing a mouse in the kitchen, and uttering a woman’s screams. The lion retreats up a tree, and the mouse snaps his fingers at the big cat, as if doing this kind of thing is all in his day’s work. The lion stops to think about it, and takes offense at the little pipsqueak showing him up. Building up his courage, the lion tugs the mouse’s tail for attention, then lets fly with a roar so powerful, it rotates his body like the cylinder of a retracting windowshade. But the lion’s fierce expression literally melts away before our eyes, as the mouse, not phased at all by the lion’s show, begins to march directly at the lion’s face. The perspiring lion withdraws backwards, until the mouse has walked up upon his torso, then all the way to his head, and takes the opportunity to lift open one of the lion’s eyelids, and spit straight into his eye. The lion tries again to get the upper hand of the situation, lying in wait in the mouse’s path with jaws wide open, and tongue unrolled upon the ground like a red carpet to the entrance. The mouse avoids being chewed by standing in a vacant spot of the lion’s gums where a tooth is missing, but is eventually swallowed into the lion’s stomach. There, he grabs two bones left over from a previous meal, and starts playing a musical xylophone solo upon the lion’s internal rib cage. To put a stop to this painful melody, the lion swallows a lit bomb. The mouse swiftly exits back through the lion’s throat, the lion unrolling his tongue to provide the mouse with a staircase for a quick departure. But the lion has forgotten all about the bomb, which emits trails of smoke out of his mouth. For about 20 seconds, the lion runs a race to nowhere, unable to escape his own person, inside which the shape of the bomb still protrudes through his tail. Finally realizing that running is pointless, the lion sadly waves bye-bye to the camera, as the explosion blasts away all meat and fur, exposing the lion’s waving skeleton. Then, the lion’s fur and head fall from the sky, back into place upon his bones.

The mouse, much in the manner of Droopy, begins to appear in every nook and cranny of the jungle, and also within a hut in which the lion hides. The rodent takes walking detours inside the lion’s hollow head, then tosses in a miniature firecracker to liven things up. He appears in a chef’s hat, basting the lion’s tail within a small stewpot. He is underwater in a miniature diver’s helmet, sticking a pin into the lion’s rear (but covering up the impact with a “censored” sign to make sure he adheres to the motion picture code). He is inside old whiskey bottles, and in the barrel of a shotgun. Even the lion’s reflection in a mirror transforms into the shape of the rodent. And all reiterating that ever-provoking “Boo”. As the lion is whacked right and left, including hammer blows to both hind feet, leaving him hopping in mid-air in defiance of gravity, sanity leaves the lion’s noggin, and he goes racing down a road in nervous fits. The scene returns to the present, as the mouse concludes his tale – but asks one question that’s been bothering him. How could anyone be afraid of a mouse? Though no logical explanation is provided, the mouse soon learns to understand the experience, as another smaller mouse appears, and utters “Boo” to him. “A mouse!”, screams our narrator, who likewise races down the road in hysterics, for the iris out. (A mystery remains concerning the ending of this film, as all reissue prints (which use the line “Made in Hollywood, U.S.A.”, which did not appear as part of titling until approximately three years after this film was made) splice on the end card for “An MGM Tom and Jerry cartoon”. Was this a laboratory error? If so, it is the only one of its type in MGM’s library, and strangely has never been corrected. Or is it possible that Avery was poking fun at the similarity of his own film to the kind of cat-and-mouse antics regularly displayed by the Hanna-Barbera unit, and playfully suggesting that this was as close a homage to the H-B characters as Avery was likely to present? As no original-issue print is known to have surfaced to date, we cannot prove or disprove therefrom if an earlier rendition of the T&J end card was used for the original release. Do any studio documents, breakdowns, or storyboards suggest the use of the T&J ending? Any insight upon this baffler will be greatly appreciated.)

The mouse, much in the manner of Droopy, begins to appear in every nook and cranny of the jungle, and also within a hut in which the lion hides. The rodent takes walking detours inside the lion’s hollow head, then tosses in a miniature firecracker to liven things up. He appears in a chef’s hat, basting the lion’s tail within a small stewpot. He is underwater in a miniature diver’s helmet, sticking a pin into the lion’s rear (but covering up the impact with a “censored” sign to make sure he adheres to the motion picture code). He is inside old whiskey bottles, and in the barrel of a shotgun. Even the lion’s reflection in a mirror transforms into the shape of the rodent. And all reiterating that ever-provoking “Boo”. As the lion is whacked right and left, including hammer blows to both hind feet, leaving him hopping in mid-air in defiance of gravity, sanity leaves the lion’s noggin, and he goes racing down a road in nervous fits. The scene returns to the present, as the mouse concludes his tale – but asks one question that’s been bothering him. How could anyone be afraid of a mouse? Though no logical explanation is provided, the mouse soon learns to understand the experience, as another smaller mouse appears, and utters “Boo” to him. “A mouse!”, screams our narrator, who likewise races down the road in hysterics, for the iris out. (A mystery remains concerning the ending of this film, as all reissue prints (which use the line “Made in Hollywood, U.S.A.”, which did not appear as part of titling until approximately three years after this film was made) splice on the end card for “An MGM Tom and Jerry cartoon”. Was this a laboratory error? If so, it is the only one of its type in MGM’s library, and strangely has never been corrected. Or is it possible that Avery was poking fun at the similarity of his own film to the kind of cat-and-mouse antics regularly displayed by the Hanna-Barbera unit, and playfully suggesting that this was as close a homage to the H-B characters as Avery was likely to present? As no original-issue print is known to have surfaced to date, we cannot prove or disprove therefrom if an earlier rendition of the T&J end card was used for the original release. Do any studio documents, breakdowns, or storyboards suggest the use of the T&J ending? Any insight upon this baffler will be greatly appreciated.)

24 – Slap Happy Lion from Looney tooney on Vimeo.

Bongo (from the feature Fun and Fancy Free (Disney/RKO, 9/27/47)) – A Sinclair Lewis tale, narrated by Dinah Shore, about a little bear in a red coat and circus cap who is the star performer of the circus. He spends most of his time riding a unicycle, but among his other claims to fame, he juggles, performs trapeze acts, wrestles, boxes, knows ju jitsu, and for a climax dives from the high wire 300 feet into a wet sponge. But all is not glitter and glamour for this performer behind the scenes, as he is quickly locked into a collar after his act, then led back to an iron-barred cage – a veritable bird in a gilded cage. At night, as the circus train chugs from town to town, (sucking up the entire big top tent as if it were being swallowed by a vacuum cleaner, then spitting it out whole just as suddenly in the next town), Bongo sees the open countryside shrouded in night darkness, and begins to hear voices, singing, “Come out, Bongo”. It is the call of the wild rising from his inner instincts, and Bongo even hallucinates to see a vision of himself sliding atop the mountaintops. As dawn breaks, so does Bongo’s tolerance for civilization and circus life. He shakes the bars on his train car as hard as he can – and to his surprise, finds that someone forgot to close the padlock on the cage door, which rattles free. Bongo makes an escape on his unicycle, then attempts to discover the wonders of nature. Sunshine, fresh air, flowers, and babbling brooks all present themselves first on the positive side of the ledger (set to the film’s closest thing to a song hit, “Lazy Countryside”). On the other side of the coin, Bongo spends a sleepless night, as the local community of insects drives him crazy with their stomping, chomping, and mosquito stings (a sequence which would be closely mirrored by Rabbit lost in a fog in “Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too”), while mother nature bombards him with a sudden rain and lightning storm (a sequence I missed mentioning in my recent article series, “Unpredictable as Weather”). And to top it off, in a running gag recurring several times in the film, Bongo discovers he can’t even climb trees.

Bongo (from the feature Fun and Fancy Free (Disney/RKO, 9/27/47)) – A Sinclair Lewis tale, narrated by Dinah Shore, about a little bear in a red coat and circus cap who is the star performer of the circus. He spends most of his time riding a unicycle, but among his other claims to fame, he juggles, performs trapeze acts, wrestles, boxes, knows ju jitsu, and for a climax dives from the high wire 300 feet into a wet sponge. But all is not glitter and glamour for this performer behind the scenes, as he is quickly locked into a collar after his act, then led back to an iron-barred cage – a veritable bird in a gilded cage. At night, as the circus train chugs from town to town, (sucking up the entire big top tent as if it were being swallowed by a vacuum cleaner, then spitting it out whole just as suddenly in the next town), Bongo sees the open countryside shrouded in night darkness, and begins to hear voices, singing, “Come out, Bongo”. It is the call of the wild rising from his inner instincts, and Bongo even hallucinates to see a vision of himself sliding atop the mountaintops. As dawn breaks, so does Bongo’s tolerance for civilization and circus life. He shakes the bars on his train car as hard as he can – and to his surprise, finds that someone forgot to close the padlock on the cage door, which rattles free. Bongo makes an escape on his unicycle, then attempts to discover the wonders of nature. Sunshine, fresh air, flowers, and babbling brooks all present themselves first on the positive side of the ledger (set to the film’s closest thing to a song hit, “Lazy Countryside”). On the other side of the coin, Bongo spends a sleepless night, as the local community of insects drives him crazy with their stomping, chomping, and mosquito stings (a sequence which would be closely mirrored by Rabbit lost in a fog in “Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too”), while mother nature bombards him with a sudden rain and lightning storm (a sequence I missed mentioning in my recent article series, “Unpredictable as Weather”). And to top it off, in a running gag recurring several times in the film, Bongo discovers he can’t even climb trees.

The next morning finds Bongo stiff, cranky, and very hungry. Although his fishing skills still need about as much practicing and refinement as his tree climbing, he soon forgets his hunger, when something more appealing whets his appetite – a little girl bear named Lulu Belle. At this point, the storyline becomes rather simple and to a degree predictable, much like so many an Aesop’s Fable, with a standard romantic rivalry between Bongo and local brute Lumpjaw, a bear four times his size. A slight detour results when an unexpected slap from Lulu Belle is misinterpreted by Bongo as an act of disdain and aggression – when in reality, Bongo’s inexperience with wild bear life leaves him without knowledge that the slap is a bear’s signal for saying, “I love you.” Eventually, as he is about to leave the forest, dejected Bongo spies a whole flock of bear couples engaging in a spirited slapping dance, and finally understands Lulu Belle’s intentions. He returns to Lulu Belle, and attempts to deliver his own message of affection with a strong slap, infuriating rival Lumpjaw. The battle for her hand commences, in which Bongo manages to avert the brute bear’s lunges and swipes by utilizing his circus unicycle experience for some fancy pedaling. At one point, he is riding his cycle atop a rolling Limpjaw, propelling him down a hill. The battle, however, reaches a cliff’s edge. A loose rock slab on which they stand topples, hurling them down into the river. Even as they are propelled toward the rapids, the bears continue their tussle, in a spirited contest of log rolling, with Bongo’s unicycle again giving him a needed edge. Finally, their log reaches the drop-off of a high waterfall. Both go over, and are thought to be lost by the other bears. But Lumpjaw survives the drop, continuing to be swept downstream as the rotating log whacks him in the head again and again. As for Bongo, he is saved by his circus cap, which catches on a branch jutting out from the falls to hold him up by the chin-strap. Bongo is reunited with Lulu Belle, strong slaps are exchanged, and the two end the film in a treetop tryst (Bongo graciously assisted up the tree by birds, squirrels, etc.), where the branches on which the two bears sit bend together to form the outline of a giant heart.

The next morning finds Bongo stiff, cranky, and very hungry. Although his fishing skills still need about as much practicing and refinement as his tree climbing, he soon forgets his hunger, when something more appealing whets his appetite – a little girl bear named Lulu Belle. At this point, the storyline becomes rather simple and to a degree predictable, much like so many an Aesop’s Fable, with a standard romantic rivalry between Bongo and local brute Lumpjaw, a bear four times his size. A slight detour results when an unexpected slap from Lulu Belle is misinterpreted by Bongo as an act of disdain and aggression – when in reality, Bongo’s inexperience with wild bear life leaves him without knowledge that the slap is a bear’s signal for saying, “I love you.” Eventually, as he is about to leave the forest, dejected Bongo spies a whole flock of bear couples engaging in a spirited slapping dance, and finally understands Lulu Belle’s intentions. He returns to Lulu Belle, and attempts to deliver his own message of affection with a strong slap, infuriating rival Lumpjaw. The battle for her hand commences, in which Bongo manages to avert the brute bear’s lunges and swipes by utilizing his circus unicycle experience for some fancy pedaling. At one point, he is riding his cycle atop a rolling Limpjaw, propelling him down a hill. The battle, however, reaches a cliff’s edge. A loose rock slab on which they stand topples, hurling them down into the river. Even as they are propelled toward the rapids, the bears continue their tussle, in a spirited contest of log rolling, with Bongo’s unicycle again giving him a needed edge. Finally, their log reaches the drop-off of a high waterfall. Both go over, and are thought to be lost by the other bears. But Lumpjaw survives the drop, continuing to be swept downstream as the rotating log whacks him in the head again and again. As for Bongo, he is saved by his circus cap, which catches on a branch jutting out from the falls to hold him up by the chin-strap. Bongo is reunited with Lulu Belle, strong slaps are exchanged, and the two end the film in a treetop tryst (Bongo graciously assisted up the tree by birds, squirrels, etc.), where the branches on which the two bears sit bend together to form the outline of a giant heart.

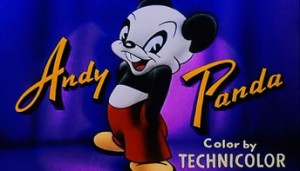

The Bandmaster (Lantz/United Artists, Andy Panda, 12/17/47 – Dick Lundy, dir.) – This may as well have been one of Lundy’s “Musical Miniatures”, performed entirely in pantomime to the strains of the “Zampa” Overture, but it was apparently thought that use of the Andy Panda series banner for release would draw bigger audience response. Andy plays conductor of the circus orchestra, providing accompaniment for various acts (though it is hard to imagine any circus band utilizing the more quiet passages of the overture, some of which impede the timing of the sight gags they underscore). Andy has recurring trouble with loud fanfares from the brass section, which repeatedly blast him off the bandstand. Another player deals with a troublesome tyke who lurks by the bandstand, trying to give the performer a hotfoot. But the player has the problem well in hand, with a miniature electric fan to extinguish the match flame, hidden inside his shoe. Another orchestra member sips hot soup from inside his kettle drum between beats. A montage of various circus acts simultaneously perform. A dog act magically transforms a great Dane into a poodle and back again, each time he passes through a hoop. A kangaroo juggler catches the balls in her pouch at the conclusion of her act, only to discover that she has knocked out her little Joey within from the impact of the balls upon his head. A trapeze girl spins by her teeth from a rope, only to have the usual false denture problem. She lands on a net and bounces back up to the rope, where the false teeth clamp onto the rear of her dress, saving her from further falls, and allowing her to strike a careless climactic pose. A troupe of acrobats is crushed flat by the weight of the fat one among them landing atop their pile. A canine human cannonball is transformed by the blast into a flying link of hot dogs. Considerable footage is consumed in the slower passages of the overture by a girl who traverses from trapeze to trapeze on her head, but when turned rightside-up is revealed to be wearing a wig and bald underneath, and by a drunken clown on the tight-wire, who has to share his inebriated walk with a trio of dancing pink elephants. Then comes the feature act of the performance – Count Bejerk, world’s greatest high diver. The confident Count scales one of those impossibly-high ladders to the top of the tent, picks out a newspaper to read on the way down, and steps off the platform. Below, Andy witnesses a horrific sight. An elephant has sucked up the entire contents of the Count’s water tank in one gulp. Andy abandons the bandstand while the orchestra continues to play furiously without its director. Finding a water tap, Andy attempts to fill a small pail full of water, and race it over to the tank for a refill.

The Bandmaster (Lantz/United Artists, Andy Panda, 12/17/47 – Dick Lundy, dir.) – This may as well have been one of Lundy’s “Musical Miniatures”, performed entirely in pantomime to the strains of the “Zampa” Overture, but it was apparently thought that use of the Andy Panda series banner for release would draw bigger audience response. Andy plays conductor of the circus orchestra, providing accompaniment for various acts (though it is hard to imagine any circus band utilizing the more quiet passages of the overture, some of which impede the timing of the sight gags they underscore). Andy has recurring trouble with loud fanfares from the brass section, which repeatedly blast him off the bandstand. Another player deals with a troublesome tyke who lurks by the bandstand, trying to give the performer a hotfoot. But the player has the problem well in hand, with a miniature electric fan to extinguish the match flame, hidden inside his shoe. Another orchestra member sips hot soup from inside his kettle drum between beats. A montage of various circus acts simultaneously perform. A dog act magically transforms a great Dane into a poodle and back again, each time he passes through a hoop. A kangaroo juggler catches the balls in her pouch at the conclusion of her act, only to discover that she has knocked out her little Joey within from the impact of the balls upon his head. A trapeze girl spins by her teeth from a rope, only to have the usual false denture problem. She lands on a net and bounces back up to the rope, where the false teeth clamp onto the rear of her dress, saving her from further falls, and allowing her to strike a careless climactic pose. A troupe of acrobats is crushed flat by the weight of the fat one among them landing atop their pile. A canine human cannonball is transformed by the blast into a flying link of hot dogs. Considerable footage is consumed in the slower passages of the overture by a girl who traverses from trapeze to trapeze on her head, but when turned rightside-up is revealed to be wearing a wig and bald underneath, and by a drunken clown on the tight-wire, who has to share his inebriated walk with a trio of dancing pink elephants. Then comes the feature act of the performance – Count Bejerk, world’s greatest high diver. The confident Count scales one of those impossibly-high ladders to the top of the tent, picks out a newspaper to read on the way down, and steps off the platform. Below, Andy witnesses a horrific sight. An elephant has sucked up the entire contents of the Count’s water tank in one gulp. Andy abandons the bandstand while the orchestra continues to play furiously without its director. Finding a water tap, Andy attempts to fill a small pail full of water, and race it over to the tank for a refill.

Unfortunately, the pail is missing a bottom. Needing more water more quickly, Andy finds and opens the valve of a fire hydrant, grabbing a hose connected to it to drag over to the empty water tank. In his haste, he yanks and disconnects the hose from the hydrant. Finding the empty tank is supported by a wheeled base, Andy wheels the tank over to the hydrant to get its water supply, putting the tank out of position from the trajectory of the descending Count, who is now taking time-out in free-fall to file his nails. The Count finally looks down, and reacts in shock at finding no tank below him. Spotting Andy, the Count attempts to change direction in mid-air, hoping to intercept the tank. But Andy is already running back with the tank in the opposite direction, and the two pass each other. Directions reverse again with the sound of a skid of brakes, but the two just can’t seem to decide on the same direction at the same time. Andy circles round the arena, still trying to get under the Count, knocking over tent pole after tent pole with the water tank. The big top falls – yet, through the same magic as encountered by Bluto in “Tops In the Big Top” last week, the Count is not dragged to the ground by the canvas. Instead, he remains in fall, somehow passing through the tent roof. Andy pops out of a hole in the canvas, carrying the water tank, and holds it out for the Count to land in. Instead, the Count plummets right through the bottom of the tank, leaving only a gaping hole in its base, while Andy shrugs his shoulders as if to write the incident off as a typical occupational hazard, communicating silently the unspoken curtain line, “Oh, well…”

Unfortunately, the pail is missing a bottom. Needing more water more quickly, Andy finds and opens the valve of a fire hydrant, grabbing a hose connected to it to drag over to the empty water tank. In his haste, he yanks and disconnects the hose from the hydrant. Finding the empty tank is supported by a wheeled base, Andy wheels the tank over to the hydrant to get its water supply, putting the tank out of position from the trajectory of the descending Count, who is now taking time-out in free-fall to file his nails. The Count finally looks down, and reacts in shock at finding no tank below him. Spotting Andy, the Count attempts to change direction in mid-air, hoping to intercept the tank. But Andy is already running back with the tank in the opposite direction, and the two pass each other. Directions reverse again with the sound of a skid of brakes, but the two just can’t seem to decide on the same direction at the same time. Andy circles round the arena, still trying to get under the Count, knocking over tent pole after tent pole with the water tank. The big top falls – yet, through the same magic as encountered by Bluto in “Tops In the Big Top” last week, the Count is not dragged to the ground by the canvas. Instead, he remains in fall, somehow passing through the tent roof. Andy pops out of a hole in the canvas, carrying the water tank, and holds it out for the Count to land in. Instead, the Count plummets right through the bottom of the tank, leaving only a gaping hole in its base, while Andy shrugs his shoulders as if to write the incident off as a typical occupational hazard, communicating silently the unspoken curtain line, “Oh, well…”

Into ‘48 and ‘49, next week.